Newcomer here. I'm happy to edit for clarity or accuracy!

TL;DR

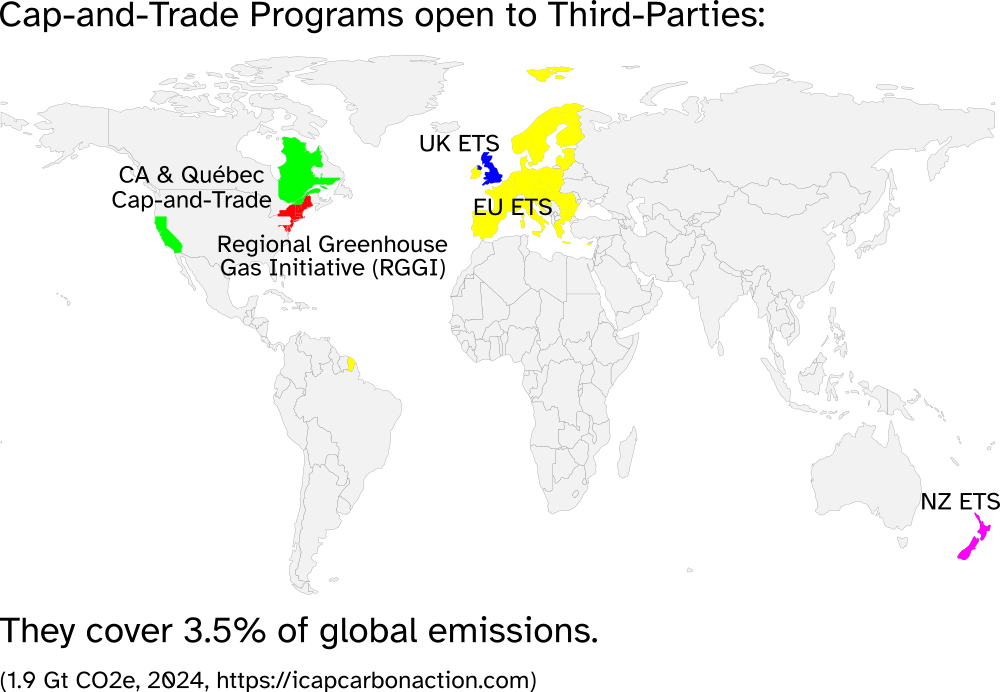

This post argues that retiring pollution allowances (the legal rights for polluters to emit CO2) is a cost-effective way to reduce global emissions. In government ”cap-and-trade” programs, polluters must buy a serial-numbered allowance to emit each ton of CO2. These allowances are sold in public auctions and secondary markets. Crucially, anyone can buy and retire allowances, reducing their availability and forcing polluters to emit one less ton. In well-designed cap-and-trade programs, allowance prices range from $20 to $85, significantly below the social cost of carbon (~ $230 according to the EPA) and most carbon-removal technologies ($300+ per ton). I discuss two key risks: leakage (the shifting of pollution outside the cap-and-trade jurisdiction) and political rollback.

Epistemic status: confident that retiring an allowance in well-designed cap-and-trade programs prevents one ton of regulated CO2 emissions at a cost equal to the market price of that allowance. Such “well-designed” programs meet the four conditions outlined in the additionality section. Less confident about the effect of retiring allowances on global fuel markets and about political risk. Numbers are for mid-2025 unless noted.

1. How Cap-and-Trade Works, and How Anyone Can Shrink the Cap.

A regulator measures the CO2 of large emitters (power plants in the U.S. Northeast, heavy industry in the E.U.). It issues a fixed number of allowances each year, the “cap”. Polluters must surrender one allowance for each ton of CO2 emitted. Failure to comply results in substantial fines. Since allowances are both scarce and tradable, polluters buy and sell them—hence, “cap-and-trade”.

The key insight is that private individuals can also buy these allowances. By permanently removing them from circulation (retiring them) they effectively lower the cap. Fewer allowances mean polluters must either reduce emissions or buy increasingly expensive remaining allowances. This mechanism allows direct emissions reduction without relying on political interventions.

2. Additionality: Why Retiring One Allowance Equals One Ton of CO2 Avoided.

Retiring an allowance reliably forces polluters to reduce emissions by exactly one ton of CO2, provided the cap-and-trade program satisfies these four conditions:

- The cap is fixed, so regulators can’t issue extra allowances to compensate for third-party retirements. Every program above sets the cap in advance (up to 2026 for New Zealand and 2030 for the others).

- Limited or no offsets allowed, so polluters cannot simply buy carbon credits instead of allowances when allowances run short. Currently, New Zealand allows polluters to offset 100% of their emissions, Québec allows 8%, California allows 5%, while the EU, UK, and RGGI programs permit no offsets.

- Accurate measurement of emissions, so the cap effectively limits them. For example, RGGI power plants use EPA-certified monitoring equipment to report hourly emissions.

- Allowances are scarce. A positive price reveals that polluters plan to use them all: polluters value allowances only because they let them pollute. If there’s excess allowances, they have to be worthless and trade for $0.

3. Comparing Other Climate Options

Relative to retiring allowances, I argue that carbon credits and renewable energy certificates have a low certainty of CO2 impact, and that carbon removal is expensive.

3.1. Carbon credits

These are tradeable certificates that registries award to those who develop climate projects. The goal is for third-parties to buy credits from developers and incentivize further climate action. They face three major challenges:

- Verification incentives are twisted: project developers choose their auditors, who have an incentive to overstate impacts to secure repeat business.[1]

- Accurately measuring the true impact of projects is hard (e.g., tree planting efforts can fail due to future fires or the unnecessary preservation of already safe habitats).

- Unclear impact: Purchasing carbon credits rewards project developers, but it remains uncertain how much additional future climate action this incentivizes.

3.2. Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs)

These are tradeable certificates granted to renewable energy producers per megawatt-hour generated. Similar to carbon credits, it's unclear how much more renewable energy generation RECs actually incentivize or how effectively renewables displace fossil fuel-based electricity.[2]

3.3. Carbon removal technologies

These include things like direct air capture or enhanced rock weathering. They’re necessary but currently expensive and uncertain. For example, Stripe’s carbon removal offerings cost between $300–$1,000, above the EPA’s $230 social cost of carbon. Additionally, some direct air capture methods (e.g., Climeworks) reportedly emit more CO2 than they capture.[3]

4. Objections and uncertainties

4.1. Leakage: Emissions Shift Elsewhere

Criticism: Retiring allowances means local producers reduce production, but producers elsewhere increase production, merely shifting emissions geographically rather than reducing them.

Response: this criticism is partially correct; the magnitude of leakage depends on industry and region. Consider RGGI, the U.S. cap-and-trade program that regulates fossil fuel power plant emissions in the Northeast. Retiring an allowance forces Northeastern power plants to either switch to cleaner power or reduce output. While this may increase power imports from other regions, these imports aren't necessarily equally polluting. Power imports into RGGI states come partially from Canadian hydro and are cleaner than local RGGI power (0.27 tCO2/MWh vs. 0.45 tCO2/MWh). Even without increased local renewable production or reduced overall demand, retiring one allowance in RGGI results in a net reduction of approximately 0.4 tCO2 (calculation: 1 - 0.27/0.45).

4.2. Risk of Cap-and-Trade Program Shutdown

Criticism: retiring allowances today is meaningless if governments shut down the cap-and-trade program tomorrow.

Response: shutdowns do not necessarily invalidate prior retirements. If polluters use all available allowances before the program ends, earlier retirements still prevent emissions during the program’s remaining active period. Conversely, if polluters have more allowances than they need to reach the end of the program, previously retired allowances lose their impact. Interestingly, this scenario would drastically lower allowance prices, creating an opportunity to cheaply retire allowances and reintroduce scarcity.

4.3. Reduced Supply of Goods and Potential Social Harm

Criticism: Reducing allowances restricts production of valuable goods and services, potentially harming society overall.

Response: this criticism is incorrect. The net social impact of retiring an allowance equals the social cost of carbon minus the value of goods produced by the marginal ton of emissions prevented. The marginal ton of emissions is the least valuable ton emitted by polluters; its value is approximately equal to the allowance price (otherwise polluters would have continued emitting it). Given allowance prices ($20–$80) are substantially lower than the social cost of carbon ($230, EPA), retiring allowances yields a net social benefit.

5. Short History

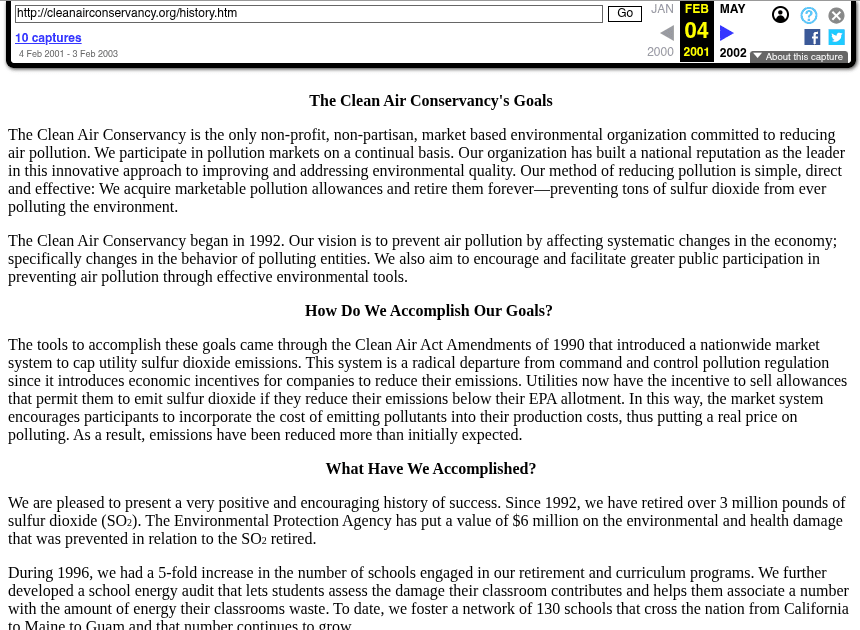

The idea of retiring allowances originated in 1992 with David Webster’s Clean Air Conservancy under the Acid Rain Program (a cap-and-trade program targeting sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides). The organization dissolved after Webster's death in 2009. Recently, economist Michael Greenstone advertised the concept (2021 podcast).

Here's the Clean Air Conservancy describing allowance retirements in 2001:

6. Back-of-the-envelope impact

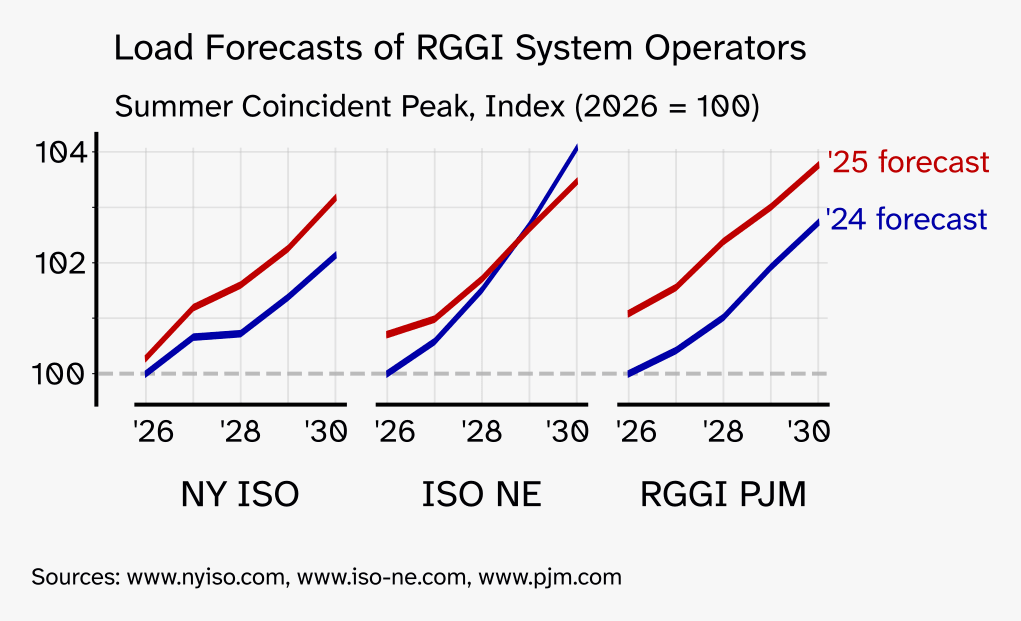

I’ll use numbers for RGGI, since it offers the cheapest allowances, ticks all additionality conditions, and has a leakage that's easy to understand (see the discussion of leakage in 4.1.).

Cost: $20 to retire one RGGI allowance (latest auction prices here).

Benefit: Avoided social damage of $230 (EPA SCC, 2025).

Benefit-cost ratio: ~12:1 before leakage; ~5:1 under worst-case 60% leakage.

7. How you can help

Comment, suggest edits, demand missing references, and criticize :)

- ^

See, for example, the definition of an Output Auditor under the puro.earth registry rules.

- ^

See the discussion and links herein: https://www.bccas.business-school.ed.ac.uk/impact-and-collaboration/renewable-energy-purchasing

- ^

See a recent article claiming that Climeworks’ capture fails to cover its own emissions.

Equal Right is testing a similar model in Palau and Tuvalu: https://www.equalright.org/

I guess you have already heard of it, but I put the link here just in case, because I really like their idea. :)

Hi Ulf, thank you for bringing up Equal Right: I was actually not familiar with it!

From their cap-and-share proposal, I gather that they advocate for a cap on emissions with allowances that aren't tradeable. An argument in favor of trading allowances is that polluters can freely redistribute allowances towards those who value them more (i.e. emit to produce more valuable things), resulting in lower pollution abatement costs. Cap-and-share involves direct government control over individual polluters, which makes climate mitigation costlier: Greenstone et al... (read more)