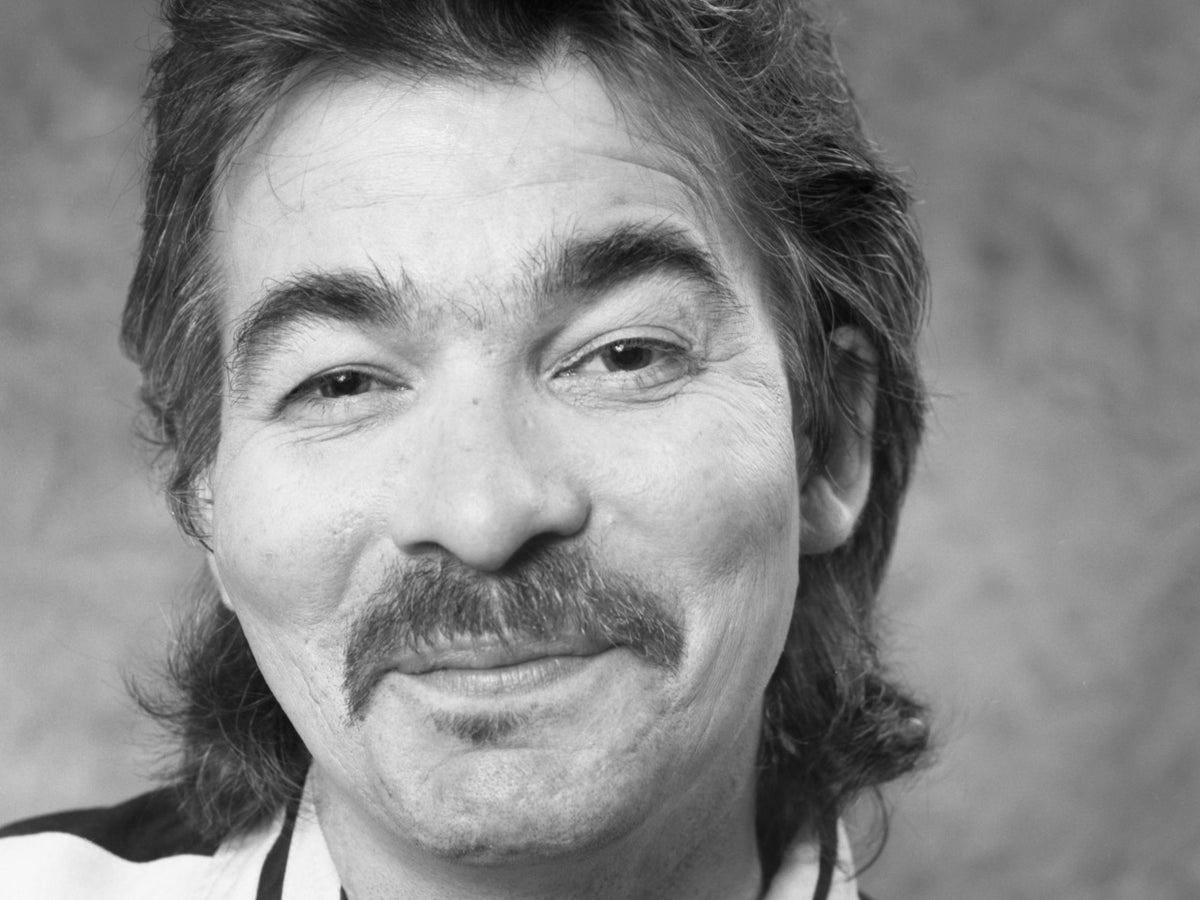

Julian Perry Robinson (1941–2020)

Leader of the campaign against chemical weapons in the UK. A chemist, he spent the first half of his career doing forensic analysis on alleged chemical agents, including a Soviet "toxin" which proved to be bee shit instead. The second half was reports, briefings, committees, meetings. Most of his work is hard to evaluate, either because it was subsumed by committees, was sub rosa, or is just part of that great majority of good work which doesn't document itself and disappears from history. I can't find a full copy of his influential anonymous 1970 WHO report which helped birth the Biological Weapons Committee. He was apparently instrumental in the UK's strong 1996 law on chemical weapons. He was the UK arm, where Matthew Meselson was the US fist. "Of the two, Meselson is seen as the ‘lightning-speed thinker’ and Perry-Robinson‘the careful, studious one’ with exhaustive files. Yet their views often echo each other, and their collaboration has held firm for almost two decades." Together they maintained (and maintain) a complete database of all chemical weapon events since 1987. His father-in-law was the great economist Nicholas Kaldor, of Kaldor-Hicks improvement fame (far more common and important than Pareto improvements). He continued to work throughout his 70s, producing an influential timeline of chemical weapon use by Assad and an analysis of the notorious novichok family of nerve agents.

An unfinished proposal, which he started pushing in the 70s, is that natural-pandemic preparedness is the best way to counter biological weapons: to make them ineffective, and so to remove all incentive to use them, and so to remove all incentive to make them.

Arianna Rosenbluth (1927–2020)

Physicist and computer scientist. During her work at Los Alamos on the H bomb, she wrote the first full implementation of a Markov chain Monte Carlo method, one of the most important algorithms of all time and the key to the recent ascendence of Bayesian statistics. During her PhD, which she got aged 21, Thomas Kuhn was a labmate. She was a world-class fencer, winning the Texas women's championship and a municipal men's championship. She qualified for the 1944 Olympics, which were cancelled owing to a war, and for the 1948s, which she didn't attend because no one would pay for her travel. Her favourite charity was the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Gita Ramjee (1956–2020)

AIDS researcher. Notable for the extremely good idea to address HIV by focussing on sex workers, and on preventions that they can actually use (microbicides). The best of these offer a 30% reduction in risk. A mere 22 years later, the European Medicines Authority endorsed this practice. In 2007 she was the target of hateful tabloid gibberish after one candidate microbicide failed and appeared to increase the risk of HIV (p=0.13). In her youth, her family was one of thousands forcibly displaced by Idi Amin in his racist campaign against Asians in Uganda. Vipul Naik tells us that the Gates Foundations has given $24m to her organisation, the Aurum Institute, which is also part of PEPFAR, one of the US's best-ever aid programmes.

Li Wenliang (1986–2020)

Opthalmologist and group chat user.

John Horton Conway (1937–2020)

As he sat on the train to Cambridge, it dawned on him that since none of his classmates would be joining him at university, he would be able to transform himself into a new person: an extrovert! He wasn’t sure it would work. He worried that his introversion might be too entrenched, but he decided to try. He would be boisterous and witty, he would tell funny stories at parties, he would laugh at himself – that was key...

In lecturing on symmetry and the Platonic solids, he sometimes brought a large turnip and a carving knife to class, transforming the vegetable one slice at a time into an icosahedron with 20 triangular faces, eating the scraps as he went.

A jester genius. We've only ever had a few of them. His discoveries stretch on and on, but include giant result in group theory ("Monstrous Moonshine"), surreal numbers, and beautiful cellular automata. Yudkowsky once admitted Conway was smarter than him, surely his greatest accolade. He was also quite tormented.

Conway: Incidentally, I was imprisoned in the same prison in which John Bunyan was imprisoned about three hundred years earlier. When I was a student I participated in a “ban the bomb” demonstration. There was a magistrate who asked everybody a few questions and then sent us to jail... So, in some sense, the book is alien to me, except that I recognize the “Slough of Despond”, a phrase he used to refer to being depressed.

Schleicher: For how long?

Conway: I was very depressed in 1993. I attempted suicide. And I very nearly succeeded. That was just personal problems — my marriage was breaking down.

Schleicher: I was asking about the prison term.

Conway: That was, I think, eleven days. That’s the number I remember.

At one point he burned out entirely and made himself The Vow: '"Thou shalt stop worrying and feeling guilty; thou shalt do whatever thou pleasest.” He no longer worried that he was eroding his mathematical soul when he indulged his curiosity and followed wherever it went, whether towards recreation or research, or somewhere altogether nonmathematical, such as his longing to learn the etymology of words.' If mathematics repels you with its humourlessness and gravity, then Conway is your man.

Toots Hibbert (1942–2020)

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/DNERIELAZZFZHMTAOS2Q5HFILU.jpg)

Singer-songwriter. Formed his band the same year Jamaica got its independence. Toured 50 years straight and named reggae "reggae" (though his own style was closer to Redding gospel). Their UK label accidentally released their early singles in the name of other bands, The Flames and The Vikings. In 1980, his band recorded, pressed and distributed a new album in less than 24 hours. It's pretty good, and played at 1.5x speed so EA podcast fans should like it. Listen.

The quick way to explain the Maytals is to say... they're the Beatles to the Wailers' the Rolling Stones. But how do I explain Toots himself? Well, he's the nearest thing to Otis Redding left on the planet: he transforms 'do re mi fa sol la ti do' into joyful noise.

John Prine (1946–2020)

Woke up this morning

Put on my slippers

Walked in the kitchen and died

Give my feet to the footloose

Careless, fancy free

Give my knees to the needy

Don't pull that stuff on me

Send my mouth way down south

And kiss my ass goodbye

But please don't bury me

Down in that cold cold ground

No, I'd druther have 'em cut me up

And pass me all around

Songwriter. He wrote a vast number of novelty songs but also some of the angriest and most noncommercial, doing Dylan better than Dylan. If you think you don't like country you probably actually do. Listen.

Adam Schlesinger (1967–2020)

Pop genius. Poet of dead-end jobs and tfw no gf. Most famous as the writer of Fountains of Wayne's best songs (yes, the Stacy's Mom guys), but the man wrote hundreds for other people and you'll have heard them or his tv scores. Listen.

Michael Lee "Meat Loaf" Aday (1947–2022)

Singer and actor. "If I die, I die, but I'm not going to be controlled." A covid sceptic, and as such a representative for the vast minority of people who, for whatever reason, have lost all trust in ruling institutions. The pop genius Jim Steinman wrote all his greatest songs, and died 9 months earlier. The apotheosis of camp trash, much like say Bizet's Carmen. People in the UK can enjoy this astonishing buffa opera.

Dave Greenfield (1949–2020)

Keyboardist and songwriter; amazing how far arpeggios will take you; amazing how much prog you can trick punks into listening to. Listen.

Ann Katharine Mitchell (1922–2020)

Cryptanalyst and psychologist. Worked with Turing on cracking Enigma; operated the Bombes. Oxford maths '43; one of only five women in her whole year. 'her headmistress sought to prevent her from applying to read Maths at university, judging the subject “unladylike”. Luckily her parents disagreed.'

We had fun sorting out the duds and also doing mathematical puzzles. There were 10 or so of us working in the Machine Room. It sounds much more complicated than we found it at the time. It was fascinating, all these messages coming out in German. I loved it... I have a diary from then, probably illegally, and I wrote in it, ‘Gosh, the secrets this place holds!’...

All those decades, and I had no idea what part in the great big machine our little cog was playing. Now everyone is talking about it

She later wrote books about the effects of divorce on children.

Paul Matewele (1958–2020)

Microbiologist. Most notable for studying pathogens in everyday life, e.g. on cash, public transport, touch screens.

Maria de Sousa (1939–2020)

Discovered how white blood cells get from the bone marrow to the tissues they're needed in, an early example of the theory of cellular niches. Discovered how toxic metals are disposed of by the lymphatic and myeloid systems, which led to hope of treatments for hereditary iron overload. Amateur poet: "I may die and you must live / In your living the hope of my lasting".

Ben Bova (1932–2020)

The last of the great pulp writers (author for trashy eC20th scifi magazines, paid by the word). He also worked on Project Vanguard, the US reply to Sputnik, as an editor. A great traditional rationalist in the mould of Sagan. His Welcome to Moonbase is a prospectus about onboarding for a moon colony in the year 2020.

My first published novel was written for teenagers, and there were rules laid down by the publisher: no sex, no smoking, no swearing. I blew up entire solar systems, I consigned billions of people to horrible death; they didn't seem to mind that at all. But no hanky-panky.

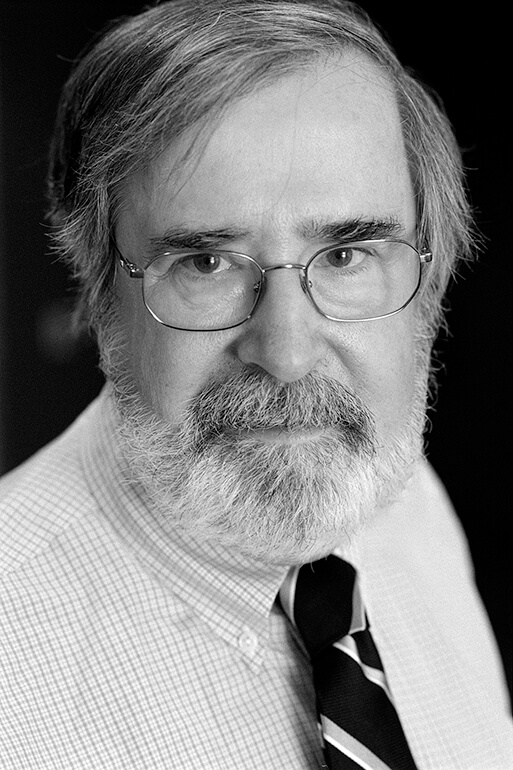

Peter M Neumann (1940–2020)

Group theorist / field theorist and historian. In 1997 he solved one of the last open geometric construction questions posed in antiquity. He published the first English edition of the works of the tragic mathematician Évariste Galois. His parents were both mathematicians, and his PhD advisor was a coauthor and family friend. A prize for writing about the history of maths was named after him, and seems to be an extremely good indicator of things worth reading.

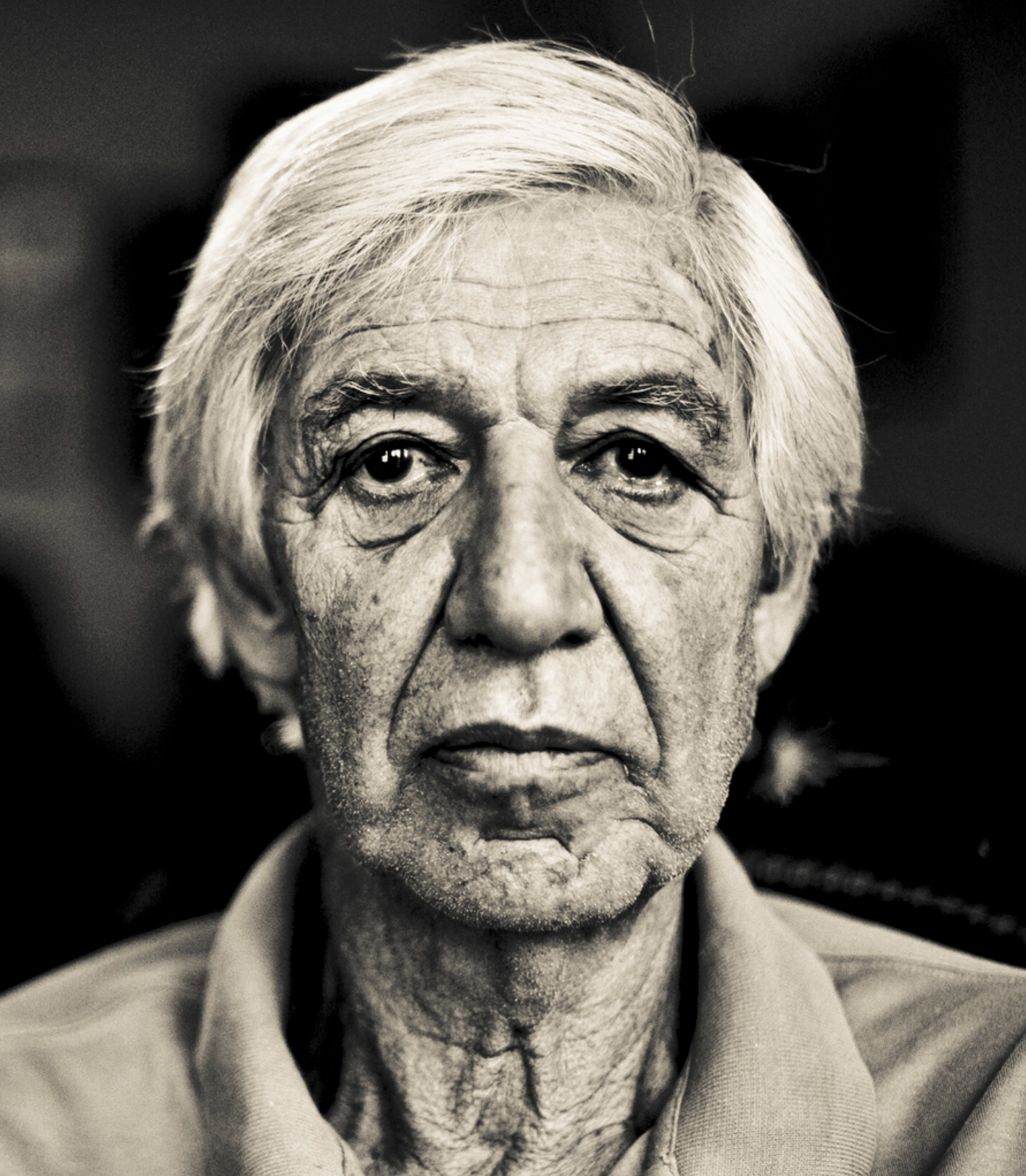

Lewis Wolpert (1929–2021)

Biologist. Most notable for explaining how embryos construct themselves. His book Malignant Sadness taught me about the bizarre theory of somatisation, by which mental illness is expressed as a physical disorder in cultures without modern psychiatric categories. Later, still publishing pop science at the age of 80, he accidentally plagiarised a bunch of writing . (I'll be amazed if this isn't extremely common.) A classic grumpy British atheist, he was often found debating theists and cranks live, or dissing bioethics.

Edmund M Clarke (1945–2020)

Computer scientist, but mostly a logician. Won the highest honour in CS for some of the earliest practical methods for automatically verifying the correctness of programs, particularly parallelised programs, and also hardware. As of 2007, model checking was "the most widely used verification method in... hardware and software". These methods were key to scaling semiconductor designs to their current unbelievable density.

Leo Goodman (1928–2020)

Statistician. Transformed the social sciences by introducing better methods for working with categories. Also the slightly dodgy but cheap idea of snowball sampling. Sylvia Plath was a fan: "I can’t tell you how much he impressed us. So brilliant, kind, versatile and so very handsome. A match, a match.”

18 people. Going off excess deaths, we lost 18-20 million extra people during the pandemic.[1] A million for each above. Try to imagine this, and fail.

- ^

or perhaps 100 million QALYs, not counting even larger nonfatal losses

This is a sobering list. I think David Graeber should have been added too. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Graeber

I guess there's a debate whether the cause of death was in fact COVID, https://www.patreon.com/posts/42824424.