Note: in response to some (much appreciated) feedback on this post, the title has been updated from "The Case for Inspiring Disasters" in order to improve clarity. The content, however, remains unchanged.

Summary

If an endurable disaster inspires a response that reduces the chance of even greater future catastrophes or existential risk, then it may be overwhelmingly net-positive in expectation. In this sense, surprising disasters which substantially change our paradigms for risk may not be worth preventing. This should be a major factor considered in the (de)prioritization of certain cause work.

Some disasters spark new preventative work.

Amidst tragedy, there are reasons to be optimistic about the COVID-19 outbreak. An unprecedented disaster has been met with an equally unprecedented response. As of June 6, 2020, over 130,000 papers and preprints related to the virus have been submitted, and governments like the USA are expected to majorly ramp up pandemic preparedness efforts for the future. As a result of COVID-19, disease-related biorisk is becoming much less neglected. This single pandemic has very likely done much more to bring attention to the dangers of disease and the fragility of our global institutions than the EA community as a whole has done in recent years. Given that pandemics are potential catastrophic or existential risks, if an endurable event like COVID-19 leads to even a modest reduction in the risk of greater pandemics in the future, its expected impacts may be overwhelmingly net-positive.

This effect isn’t unique to the current pandemic. When high-profile disasters strike, calls for preventative action are often soon to follow. One example is how after the second World War, the United Nations was established as a means of preventing future conflicts of scale. Although the 20th century from then on was far from devoid of conflict, the UN played a key role in avoiding wars and has been the principle global body working to prevent them since. While a calamity, World War II was at least endurable. But what if it has been delayed by several decades? Then it’s at least plausible that in the latter half of the 20th century, a world without a UN would be to avoid an alternate World War II, but this time with widespread nuclear arms.

These disasters need not even be particularly devastating in an absolute sense. Another striking example is the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Quickly following them, governments worldwide introduced major new security measures, and no attack of the same type has been successful ever since.

An illustrative toy model

Consider two types of disasters: endurable and terminal. Suppose that each arrives according to a poisson process with rates of ε and τ respectively. Should a terminal disaster arrive, then humanity goes extinct. However, should an endurable one arrive, let its severity be drawn from an exponential distribution with rate parameter λ, and if that severity surpasses some threshold α for inspiring preventative future action, let ε and τ decay toward a base rate by a factor of γ as a result of this response.

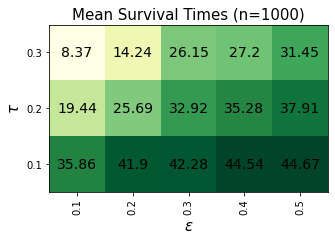

Although overly simple, this model captures why avoiding certain endurable disasters may not be good. Letting λ=α=1, γ=0.99, and using asymptotic base disaster rates of 0.05 and 0.02 for endurable and terminal disasters respectively, here are simulated mean survival times for civilizations under various values of the initial ε and τ.

Obviously, increasing τ consistently reduces mean survival time. But increasing ε, at the cost of resulting in more endurable disasters, causes large increases in the mean survival times under this model regardless of τ. So long as the wellbeing of future civilization is substantially valued and that human extinction is seen as much more tragic than an endurable disaster (there is a strong case for this viewpoint), this suggests that endurable disasters which inspire action to prevent future catastrophes are highly valuable.

Implications

I argue that the potential for endurable disasters to inspire actions that can prevent more devastating disasters in the future should be a major factor in evaluating the effectiveness of working on certain causes. This perspective suggests that working to prevent these risks may be overwhelmingly net-negative in expectation. However, this perspective does not diminish the importance of work on (1) avoiding risks that are likely to be terminal (e.g. AI), (2) preventing catastrophic risks that aren’t likely to inspire successful preventative responses (e.g. nuclear war), (3) avoiding risks whose impacts are delayed with respect to their cause (e.g. climate change), and (4) coping strategies for risks which may not be preventable (e.g. natural disasters).

However, some highly-speculative examples of causes that this model suggests may actually be counterproductive include:

- Pandemic flu

- Lone-wolf terrorism with weapons of mass destruction

- Lethal autonomous weapons

- Safety failures in self-driving cars

___

Thanks to Eric Li for discussion and feedback on this post.

I share in your hope that the attention to biorisks brought about by SARS-CoV-2 will make future generations safer and prevent even more horrible catastrophes from coming to pass.

However, I strongly disagree with your post, and I think you would have done well to heavily caveat the conclusion that this pandemic and other "endurable" disasters "may be overwhelmingly net-positive in expectation."

Principally, while your core claim might hold water in some utilitarian analyses under certain assumptions, it almost definitely would be greeted with unambiguous opprobrium by other ethical systems, including the "common-sense morality" espoused by most people. As you note (but only in passing), this pandemic truly is an abject "tragedy."

Given moral uncertainty, I think that, when making a claim as contentious as this one, it's extremely important to take the time to explicitly consider it by the lights of several plausible ethical standards rather than applying just a single yardstick.

I suspect this lack of due consideration of other mainstream ethical systems underlies Khorton's objection that the post "seems uncooperative with the rest of humanity."

In addition, for what it's worth, I would challenge your argument on its own terms. I'm sad to say that I'm far from convinced that the current pandemic will end up making us safer from worse catastrophes down the line. For example, it's very possible that a surge in infectious disease research will lead to a rise in the number of scientists unilaterally performing dangerous experiments with pathogens and the likelihood of consequential accidental lab releases. (For more on this, I recommend Christian Enemark's book Biosecurity Dilemmas, particularly the first few chapters.)

These are thorny issues, and I'd be more than happy to discuss all this offline if you'd like!