The extraordinary value of ordinary norms

This research was conducted during a 5 week fellowship at the Centre for Effective Altruism. With thanks to Stefan Schubert, Max Dalton, Owen Cotton-Barratt, Justis Mills, Danae Arroyos, Patrick Miller, Ben Garfinkel, Alex Barry, Christian Tarsney, and Daniel Kokotajlo for their comments on this article.

The value of following norms

A supply of clean water is useful to all the members of a community. But if there is no other easy way to dispose of rubbish, any individual has an incentive to pollute the water. A little pollution won’t matter, so each individual might think it best to pollute. But if all individuals respond to this incentive, the total pollution ruins the water supply, destroying the public good.

One way of avoiding the problem is to set up social norms, and punish those who break the norms. You might fine or shun those who pollute the water supply. This will disincentivize pollution, and protect the supply for everyone.

Common-sense morality emphasizes the value of following social norms such as honesty and cooperation. Trust helps communities to cooperate, so we have a norm against lying. Helping others can make everyone better off, so we have a norm that we ought to help others. Being intellectually fair can help people to resolve disagreements, so we have norms against overconfidence and fallacious reasoning. We can call social common goods such as trust social capital. Breaking norms, and therefore destroying social capital, generally is punished with a worse reputation.

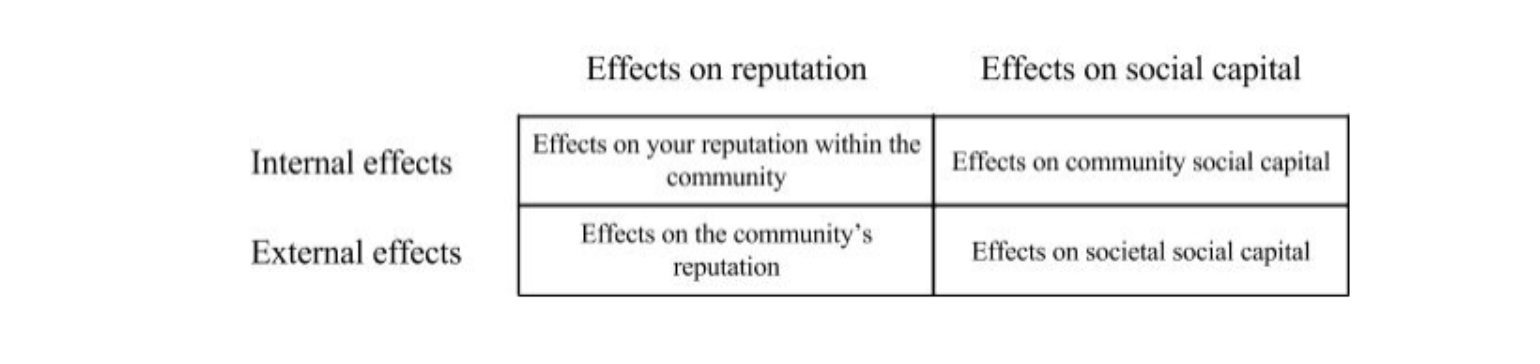

This means that there are normally two costs to breaking social norms. First, a broken norm damages the common good. The water supply is slightly poisoned; social capital is diminished. Second, the offender is harmed directly through punishment. They can expect to have a worse reputation if caught, and, in extreme cases, might suffer ostracization or job loss. Both effects are amplified when an offender acts within a community: not only does the individual damage the public good and risk retribution within the community, but the community itself may also suffer reputational effects as a whole. Since the community normally has a much more significant reputation than an individual, this extra effect can be large. For example, if a member of the community commits a crime, not only will that member be less well respected within the community, but also the community as a whole will look worse and more extreme.

Deontologists argue that breaking key social norms, e.g., of honesty, is intrinsically wrong. Consequentialists dispute this and argue that norm-breaking should be evaluated by its costs and benefits. It might therefore seem that consequentialists should frequently advocate norm-breaking for the greater good. However, because of large costs to reputation and social capital, even consequentialists should normally follow social norms. There is thus considerable convergence between deontologists and consequentialists, at least when it comes to typical situations and common moral choices.

But following common-sense norms may not be enough. In some cases the benefits of social capital and good reputation are stronger than is normally realized, particularly when agents represent both themselves and a community. When acting as community members, agents should go further in following social norms than common-sense morality requires.

We have identified four norms which altruists have reason to follow with extraordinary fidelity, but which are often followed imperfectly. (See the concluding remarks for a discussion on how these norms were chosen.)

Be intellectually humble

The value of being intellectually humble

Intellectual humility is a recognition that one’s beliefs may be false. This recognition may make an agent more likely to update their beliefs when presented with new convincing evidence, which should make their beliefs more accurate in expectation. It is particularly important for effective altruists to be intellectually humble because effective altruism is about using evidence and reason to do as much good as possible. Holding correct beliefs (or as close to correct as we can) both as individuals and as a community is very important for doing good. Holding incorrect beliefs about the best ways to do good normally leads to lower impact - it could even cause net impact to be negative.

Why we underestimate the extent to which we should be intellectually humble

Humans do not tend to be intellectually humble. Instead, we are systematically overconfident. There are three ways in which we can characterise overconfidence: overestimation, overplacement, and overprecision.

First, overestimation of one’s performance, ability or success. For instance, when students rate their exam performance, they systematically overestimate how well they did.

Second, overplacement - the overestimation of one’s performance relative to others. For instance, 93% of a sample of American drivers and 69% of a sample of Swedish drivers reported that they were more skillful than the median driver in their own country.

Finally, overprecision - an excessive confidence in one’s epistemic beliefs. This is the most pervasive of the three biases. When people are 90% confident of something, they are correct less than 50% of the time. Intellectual humility mitigates against this overprecision.

Overprecision is a bigger problem when making forecasts, because it leads individuals to neglect other decision aids, such as statistical evidence. Effective altruists are normally interested in forecasting their actions into the future, and often into the long term future, so this fact makes overprecision particularly worrying for effective altruists.

Intellectual humility is the opposite of overconfidence, so we think that practicing extraordinary intellectual humility may be a way to counteract overconfidence.

Potential costs of being intellectually humble

There appear to be some benefits to overconfidence. People generally perceive overconfident individuals as having a higher social status within a group. If everyone in the effective altruist community rewarded intellectual humility, it might counteract this effect internally. However, overconfidence might still have benefits in other communities.

Overconfidence might also help people ‘seem smart’ - a specific type of social status. But in the long term, overconfidence is likely to be exposed by mistakes. If someone expresses high confidence in something, and then it is revealed to be conspicuously false, then that person’s reputation is likely to suffer. On the other hand, having a reputation for intellectual humility may help build credibility. Suppose that you often say ‘I could be wrong about this’. Then one day you say ‘I am very confident that I am right about this’. Given your history of caution, people are likely to take your second idea more seriously than they would if you were frequently confident.

As with many crucial norms, there are clearly complex tradeoffs to be made between the costs and benefits of overconfidence. However, (somewhat ironically) we are more confident about this norm being valuable than we are about the other norms in this article.

How to be extraordinarily intellectually humble

-

Search for flaws in your own reasoning. Try to work out the ways in which your current beliefs might be wrong.

-

Admit to those flaws. If someone else points out a problem with an argument you make, try to acknowledge that.

-

Be curious about other people’s opinions. Try to understand the arguments of people who disagree with you and be open to the possibility that they may be correct and that you may have made a mistake.

Have collaborative discussions

The value of having collaborative discussions

As a community, we are trying to figure out how to do the most good possible. This is a difficult problem, and we need to work together to solve it.

Studying the best ways of doing good often involves discussions on ethical positions and choices that may be important parts of people’s identities. It is easy for discussions of such important issues to turn into antagonistic debates or disputes.

Such disputes are unlikely to lead to the right answer. A collaborative discussion is more likely to help all parties approach the correct answer.

Moreover, conflict could lead to the movement splitting. Examples of other movement splits include the split between the suffragists and the suffragettes in the early 20th century, the radical abolitionists and the moderate antislavery reformers in the 18th and 19th century, and the civil rights movement and the black power movement in the late 20th century. These splits tend to occur due to complex ideological conflicts, which become more problematic as movements grow. Collaborative discussions might help to resolve such conflicts.

Why we underestimate the value of collaborative discussions

People often have a hard time discussing sensitive issues collaboratively. For most people, the instinctive response to criticism is to be defensive. This defensiveness can be reinforced by cognitive biases. For example, when people are presented with someone else’s argument, they are generally very good at spotting the weaknesses. But when they examine their own arguments, they are much worse at finding flaws. This is an example of a self-serving bias, which occurs due to the need to maintain and enhance self-esteem. Trying to be extraordinarily collaborative can help overcome this bias.

Potential costs of having collaborative discussions

Having collaborative discussions is hard. We must overcome our natural bias to ‘win’ each discussion. However, the benefits of collaborative discussion seem to outweigh the cost of this effort. We are reasonably confident that this norm is valuable.

How to have extraordinarily collaborative discussions

-

Aim for the highest levels of the disagreement hierarchy. Paul Graham has developed a way to classify forms of disagreement. The best collaborative discussions will employ the higher level forms of disagreement such as addressing the argument and addressing the central point. A collaborative discussion will avoid the lower levels of the hierarchy (name calling, ad hominem arguments, responding to tone). Read more about the hierarchy here.

-

Use the Center for Applied Rationality’s (CFAR) double crux technique. This technique involves working out the fundamental reason (or crux) for one’s belief and one’s discussion partner’s contradictory belief. For example, imagine I believe A and my discussion partner believes not A. The crux of the argument, B, is something we also both disagree on, and which, if either of us changed our minds about B, it would also change our mind on A. By identifying the crux, you can look for experiments to test the crux. For instance, B might be something which has been researched, or that can be observed. Read more here, and read a criticism of the technique here.

-

Paraphrase the other person’s position. This allows you to establish whether you have fully understood what they were trying to communicate.

-

Take pride in having changed your mind and compliment people who demonstrate an ability to change their mind. This comprises another norm that works in concert with having collaborative discussions.

-

Keep calm. By staying calm, you can discuss a topic more objectively and are less likely to become defensive.

Be extraordinarily honest

The value of being extraordinarily honest

Honesty requires refraining from lying. But our conception of honesty entails more than that. It also means avoiding misleading people in other ways. (Some might conceptualize this as intellectual honesty). On this conception, presenting the truth in such a way that people are likely to misinterpret it is dishonest. For example, consider the following famous exchange between Bill Clinton and Jim Lehrer during the Lewinsky scandal:

Lehrer: “No improper relationship”: define what you mean by that.

Clinton: Well, I think you know what it means. It means that there is not a

sexual relationship, an improper sexual relationship, or any other kind of improper relationship.

Lehrer: You had no sexual relationship with this young woman?

Clinton: There is not a sexual relationship – that is accurate.

There had been a sexual relationship between Lewinsky and Clinton. But Clinton’s statement was technically true: at the time of the interview, Clinton and Lewinsky were no longer sexually involved. This way of deceiving by telling the truth is known as paltering. It falls under our conception of dishonest behaviour.

A close parallel can be drawn between effective altruists and scientists. We expect scientists to be extremely honest when presenting their results and theories: we expect them to discuss the reasons why they might be wrong, and share disconfirming data. Effective altruists should be held to similarly high standards.

We often underestimate the negative indirect effects of being dishonest. These effects are even stronger within a community.

For example, Holden Karnofsky and Elie Hassenfeld, the two founding staff of GiveWell, promoted GiveWell on several blogs and in email forums either by disguising their identities and not revealing their associations with GiveWell. This practice is known as astroturfing.

Of course, such tactics might have garnered GiveWell more donations to effective charities. However, we think that the costs of this dishonesty outweighed the benefits. Karnofsky and Hassenfeld were found out, damaging the reputation of GiveWell. If GiveWell had not admitted their dishonesty, this could have further harmed their reputation, meaning fewer donations in the long run. And since the organisation is affiliated with the effective altruism community, this could also have harmed the community’s reputation significantly.

In fact, GiveWell reacted in an extraordinarily honest manner. They issued a full public disclosure and apology, and directly notified all existing donors of the incident. They also have a full record of the incident on their ‘Our Mistakes’ page on their website. The dishonesty was still damaging, but somewhat mitigated by complete honesty after the fact.

Dishonesty is also ‘contagious’. If people around you are being dishonest, then you are more likely to be dishonest. This means that communities become either predominantly honest or predominantly dishonest, since individuals joining the community adapt to the level of honesty. So people trying to do good should favour honesty, in part to encourage honesty in others.

Honesty can also be very helpful when an agent turns out to have been wrong. If I promote a cause I’m very confident in, and lie, I may persuade more people to join my cause. But later, if it turns out that I am wrong in my private reasoning, then the magnitude of my mistake is multiplied by the number of people I deceived. If, on the other hand, I am open with my honest reasoning, other people are at liberty to discover my mistake and prevent a bad outcome.

Potential costs of being extraordinarily honest

Some might argue that there are significant costs to being extraordinarily honest. First, being honest opens you up to more criticism, which may damage your reputation. If you share details about what you did, people are more likely to find mistakes you make. But often this criticism helps you to work out how to improve, and this benefit outweighs costs to your reputation.

Another cost is that some forms of honesty can be perceived as unkind. For example, telling someone that they are unskilled at something is likely to upset them, even if it is objectively true. However, there are often ways of delivering honest feedback which are kinder. These might involve careful phrasing, and offers of help.

The costs of honesty can sometimes be significant. However, we believe that they are outweighed by the long-term benefits of honesty more often than most people are inclined to think.

How to be extraordinarily honest

It is difficult to be extraordinarily honest. There has been little research into concrete ways in which individuals can reduce micro-deceptions.

-

Write yourself a personal commitment to be exceptionally honest and sign it. A study by Lisa Shu and colleagues found that declaring their intentions to be honest led to participants actually being more honest. This practice is also enacted at Princeton University where the undergraduates sign an Honour Code, stating that they will not cheat in their exams. The exams are subsequently taken without any supervision.

-

Apply debiasing techniques to prevent unintentional intellectual dishonesty. Debiasing can be difficult to do in practice. Just being aware of a bias doesn’t solve it. To prevent confirmation bias, one valuable technique is to “consider the opposite”, e.g., actively generate arguments which contradict your initial position. More information about debiasing can be found here.

Assist others

The value of assisting others

Suppose that one person has set up an effective altruist research group and does not think that funding the arts is high impact. Another person has set up an art restoration charity which does not align with effective altruist values. However, both people know donors who might be interested in the other person’s cause. They can make mutual introductions at a very low cost which both would significantly benefit from. Thus they are both better off if both parties make relevant introductions.

When we can, we should assist others from outside the community in this way. Besides the benefits this gives to them, helping others boosts the reputation of us individually and as a community. The obvious caveat to this is that we should not help organisations and individuals which cause harm.

Effective altruists have an even stronger motivation to help others within the community. If you help someone who has the same goal, then you both move closer to that goal. Nick Bostrom was one of the first people to work on reducing existential risk. Kyle Scott also cared about existential risk, and chose to become Nick Bostrom’s research assistant. He reasoned that if he could save Bostrom one hour spent on activities besides research, then Bostrom could spend an extra hour researching. In this way, he could multiply his impact.

Why do we underestimate the extent to which we should assist others

Our own impact is often more salient to us than others’ impact. We might prefer to have direct impact ourselves, since we will receive more credit that way. These factors mean that we probably don’t value others’ impact enough, and don’t spend enough time helping them. We can help overcome this bias by assisting others to an extraordinary degree. We can also give credit where it is due, in order to make people more confident that if they are helpful, their impact as a helper will be recognized.

Potential costs of assisting others

Assisting others often takes time, money and energy. However, we can often help others even with little effort. Take Adam Rifkin, who is LinkedIn’s best networker. Rifkin founded numerous technology startups. As his success grew, he received more and more requests for help and advice. He therefore decided to assist others in a particular way. He pledged to make three introductions per day between people who could benefit from knowing each other. This gave him the time and energy to focus on his own projects while still managing to help others to an extraordinary extent. Some favours will be too big to grant, but you can still generate lots of value through smaller interventions.

Of course, some people will accept your assistance but not reciprocate. They will receive all the benefits of cooperation while not incurring any costs on themselves. This is known as the free-rider problem. Free-riding undermines the norm of cooperation, which makes it less likely that help is given when needed.

One way to reduce free-riding is to increase individual identifiability. For instance, we could publicly reward those who are perceived as being exceptionally helpful.

The costs of assisting others to an extraordinary degree may sometimes outweigh the benefits, particularly for people whose time is very valuable. So this norm should not be followed mechanically: keep an eye out for chances to help others, and confirm that the opportunities you take actually produce value.

How to assist others to an extraordinary degree

It is important to consider the best ways in which you can assist others. You should share your expertise. If you know lots about design, but not much about writing, you should probably turn down requests for help with writing, and focus on helping those who need design advice. In particular, you should probably think about your comparative advantage: what are you good at, relative to others in the community? If you are a decent programmer in a community of excellent programmers, you should perhaps focus on sharing other skills.

Some specific suggestions for ways in which you can assist others:

-

Share knowledge. If you know a lot about an area, help others to learn by writing up what you’ve found.

-

Make introductions. Making introductions is a low cost, high benefit action. You might not be able to help someone personally, but you can introduce them to someone who can.

-

Provide hands-on project support. This often has high costs in time and effort. You can mitigate against this by agreeing to help them in a way where you have a lot to add. For example, if you have experience with building websites, you could help someone set up a website for their project, rather than helping with many aspects of the project.

-

Give advice or guidance.

Concluding remarks

These norms were selected through analysing common norms on LessWrong and the Effective Altruism Forum, and creating a long list of norms. Through extensive discussion with other effective altruists and a poll, these norms emerged as particularly promising.

Of course, the four norms discussed here are not the only norms which we should adhere to. If you are trying to help others effectively, you should, for instance, generally act considerately and avoid being insulting. However, people generally adhere to those norms quite well in daily life. We selected these four because their value might be underestimated - because people have biases against following them.

If these norms are as valuable as they appear, we should also promote them. We ought to reward adherence to these norms and punish noncompliance. For example, we could introduce an honor code to guard against dishonesty. Building systems to spread these norms could also help spread the norms beyond the effective altruist community and thus increase societal social capital.

If you have found these arguments convincing, we recommend that you get involved in the effective altruism community in person (if you haven’t already done so). Many of these norms are difficult to adhere to. By getting involved with a local group or attending an EAGx/ EA Global conference, you may become more motivated to follow these norms. Finally, you should praise others for adhering to these norms since this will lead to their further promotion.

WRT humility, I think it's important to distinguish between public attitudes, in-group attitudes, and private attitudes. Specifically, when it comes to public humility, while people in general probably tend to express overconfidence from a greater-good perspective (signaling 101, lemons problem, etc) I'm not sure that EAs do, especially to an extent that hurts EA goals. There are costs to public humility which don't appear in other realms, specifically people attach less belief to what you have to say. I have seen many conversations where "I'm not an expert in this, but..." is met with extreme hostility and dismissal, whereas overconfident yet faulty beliefs would be better accepted.

It's reasonable to suppose that ordinary norms have evolved to optimize the level of public humility which most strongly bolsters the speaker's reputation in a competitive marketplace of ideas. So if we are more publicly humble than this, then we should expect to have less of a reputation. This can be acceptable if you have other goals besides supporting your own reputation and ideas, but it should be kept in mind. It's one reason to have different attitudes and goals for outward-facing discussions than you do for inward-facing discussions.

That's not just a violation of extraordinary honesty. That's straight-up deception. It doesn't have much to do with the claim that we should be extraordinarily honest. Ordinary common sense morality already says that astroturfing is bad.

Are you suggesting that we should observe a bimodal distribution of honesty within communities? I'm not sure if that matches my observations.

Perceptions of dishonesty may encourage people to be dishonest but that is subtly different from dishonesty.

Again, lying is a violation of ordinary honesty, not extraordinary honesty. I'm still at a loss to see what demands us to be extraordinarily honest. It might help to be more clear about what you mean by honesty above-and-beyond what ordinary morality entails.

I don't know if this has been the case.

I think that historically most criticism leveled at EA has not really helped with any of our decisions. E.g., when people complained that Open Phil had too many associations with its grant recipients. Does that help them make better grants? No, it just took the form of offense and complaints, and either you think it's a problem or you don't. It's easy to notice that Open Phil has lots of associations with its grant recipients, and whether you think that is a problem or not is your own judgement to make; Open Phil clearly knew about these associations and made its own judgements on the matter. So a chorus of outsiders simply saying "Open Phil has too many associations with its grant recipients!" doesn't add anything substantial to the issue. If anything it pollutes it with tribalism, which makes it harder to make rational decisions.

Reputation boosts to oneself and our community are already "accounted for", though. The basic logic of reciprocation and social status was part of the original evolution of morality in the first place, and are strong motivations for the people all over the world who already follow common sense morality to varying degrees. So why do you think that ordinary common-sense morality would underestimate this effect? To borrow the ideas from Yudkowsky recently posted here, you're alleging that this system is inadequate, but the incentives of the system under consideration are fundamentally similar to the things which we want to pursue. So you're really alleging that the system is inefficient, and that there is a free lunch available for anyone who decides to be extraordinarily helpful. I take that to be an extraordinary claim. Why have all the politicians, businessmen, activists, political parties, and social movements of the world failed to demonstrate extraordinary niceness?

I don't see why this follows.

Moral trade is not premised upon the assumption that the people you're helping don't do harm. It makes it more difficult to pull off a moral trade, but it's not a general principle, it's just another thing to factor into your decision.

Maybe you mean that we will realize special losses in reputation if we help actors which are perceived as causing harm. But perception of harm is different from harm itself, and we should be sensitive to what broader society thinks. For instance, if there is a Student Travel Club at my university, helping them probably harms the world due to the substantial carbon dioxide emissions caused by cruise ships and aircraft and the loss in productivity that is realized when students focus on travel rather than academia and work. But the broader public is not going to think that EA is doing something wrong if the EA club does something in partnership with the Student Travel Club.

Right, and here again, I would expect an efficient market of common-sense morality, in a world of ultimately selfish actors, to develop to the point where common sense morality entails that we assist others to the point at which the reciprocation ends and the free-riding begins. I don't see a reason to expect that common sense morality would underestimate the optimal amount of assistance which we should give to other people. (You may rightfully point out that humans aren't ultimately selfish, but that just implies that common sense morality may be too nice, depending on what one's goals are.)

Social groups and individuals throughout human history have been striving to identify the norms which lead to maximal satisfaction of their goals. The ones who succeed in this endeavor obtain the power and influence to pass on those norms to future generations. It's unlikely that the social norms which coalesce at the end of this process would be systematically flawed if measured by the very same criteria of goal-satisfaction which have motivated these actors from the beginning.