| This is a Draft Amnesty Week draft. It may not be polished, up to my usual standards, fully thought through, or fully fact-checked. |

Commenting and feedback guidelines:

|

I claim that in scope-sensitive biosecurity, it is important to focus on developing and deploying broad defense technologies like super-PPE, air filtration, and far-UVC. Given that we have limited resources, maybe more people should be working on these technologies instead of other things.

The premises are:

- The risk of catastrophic pandemics in the next decades seems significant; let's say >1% chance of a pandemic killing >100M people by 2050 (these numbers are made up)

- Even with much better pandemic prevention and early detection approaches, we only delay the eventual outbreak. At some point, a horrible pandemic will start. This point is especially relevant if you are mostly concerned about bioterrorist threats because competent terrorists could plausibly circumvent prevention measures.

- With the worst case scenarios we are worried about, medical countermeasures (MCMs) like vaccines and antivirals will take way too long to develop and deploy since they probably need to be specific enough for the emerging pathogen.

- In that case, the most crucial defenses will be broad defenses like super-PPE, air filtration, and far-UVC that work against many different kinds of threats

Passive defenses

The great thing about air filtration and far-UVC (and maybe microwave inactivation and triethylene glycol if they work) is that you can install them and mostly forget about them since they work passively. Humans are lazy and often make mistakes, so you can't trust them to actually start wearing PPE and wearing it properly. With widespread far-UVC, for example, you could theoretically nip an outbreak in the bud without ever learning that it happened!

Counterarguments

- There is no law of physics or physical limitation preventing the development and deployment of vaccines or antivirals within one day.

- Yes, pathogens spread exponentially fast, but human engineers can, for example, create vaccine doses even faster if they work really hard.

- "Physics is on your side" (h/t Gregory Lewis)

- We can hopefully develop pan-viral-family vaccines and antivirals that would probably be helpful in many biothreat scenarios

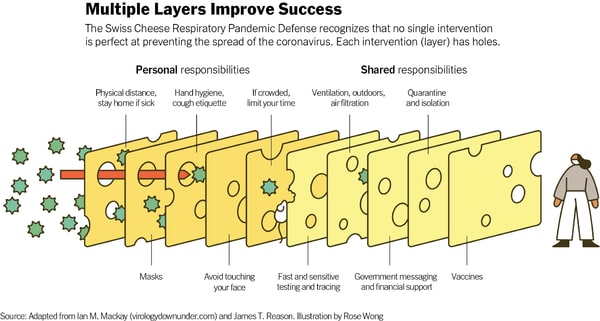

- the Swiss cheese model[1] is important and true, and we should work on all possible layers of prevention, detection and defense

- I agree that we shouldn't put all of our efforts into the broad defenses described above, but my claim is about relative importance and how we spend our resources.

- If I were the czar of biosecurity resources, then I would probably only re-distribute them marginally differently and focus slightly more on broad defenses

- I agree that we shouldn't put all of our efforts into the broad defenses described above, but my claim is about relative importance and how we spend our resources.

- prevention is still our best bet since it is much better to prevent an outbreak outright than to need to defend against it

- counter: prevention is really hard! Technocratic solutions seem much easier.

- international diplomacy, like strengthening the BWC, is famously extremely difficult and slow

- on the other hand, DNA synthesis screening seems like a good technocratic approach to the prevention of bioterrorist threats

- counter: prevention is really hard! Technocratic solutions seem much easier.

- counter: broad, passive defenses like widespread far-UVC are also kind of like prevention because they could hypothetically stop an outbreak by preventing the first-ever transmission between patient zero and the next few people

- they might also act as a deterrent because malevolent actors might think: "It doesn't even make sense to try this bioterrorist attack because the broad & passive defense system is so good that it will stop it anyways"

- to be fair, this is hopefully also true for early-warning systems

- they might also act as a deterrent because malevolent actors might think: "It doesn't even make sense to try this bioterrorist attack because the broad & passive defense system is so good that it will stop it anyways"

- I am probably biased toward broad, passive defenses because I worked on far-UVC for a while

- There could be some subconscious motivated reasoning going on to make my research seem more important

Thanks for writing this! I like the post a lot. This heuristic is one of the criteria we use to evaluate bio charities at Founders Pledge (see the "Prioritize Pathogen- and Threat-Agnostic Approaches" section starting on p. 87 of my Founders Pledge bio report).

One reason that I didn't see listed as one of your premises is just the general point about hedging against uncertainty: we're just very uncertain about what a future pandemic might look like and where it will come from, and the threat landscape only becomes more complex with technological advances and intelligent adversaries. One person I talked to for that report said they're especially worried about "pandemic Maginot lines":

I also like the deterrence-by-denial argument that you make...

... though I think for it to work you have to also add a premise about the relative risk of substitution, right? I.e. if you're pushing bad actors away from BW, what are you pushing them towards, and how does the risk of that new choice of weapon compare to the risk of BW? I think most likely substitutions (e.g. chem-for-bio substitution, as with Aum Shinrikyo) do seem like they would decrease overall risk.

Very useful comment, thanks!

I fully agree with this; I think this was an implicit premise of mine that I failed to point out explicitly.

Great point that I actually haven't considered so far. I would need to think about this more before giving my opinion. It seems really context-dependent, though, and hard to determine with any confidence.

Also, the Maginot line analogy is cool; I hadn't seen that before. (I guess I really should read more of your report 🙂)

I'm personally not that worried about substitution risks. Roughly: The deterrence aspect is strongest for low-resource threat actors and—from a tail-risk perspective—bio is probably the most dangerous thing they can utilize, with that pesky self-replication and whatnot.

Thanks, Max! One follow-up — you write:

I'm a bit surprised that this is true, given what seems to me from afar to be inordinately more spending and research on vaccines/MCMs relative to this entire bucket of passive interventions combined.

When you say "czar of biosecurity resources," are you thinking of the resources of national governments, those of this community, etc.? Or was there some other specific reference group you were thinking of? I'd also be curious if you could be a bit more quantitative about how much you'd prefer to shift to passive/broad mitigations on the margins, or even if you have takes on the relative distribution between items in that bucket (though also get that putting numbers on this is tricky).