(Crossposted from twitter for easier linking.) (Intended for a broad audience—experts already know all this.)

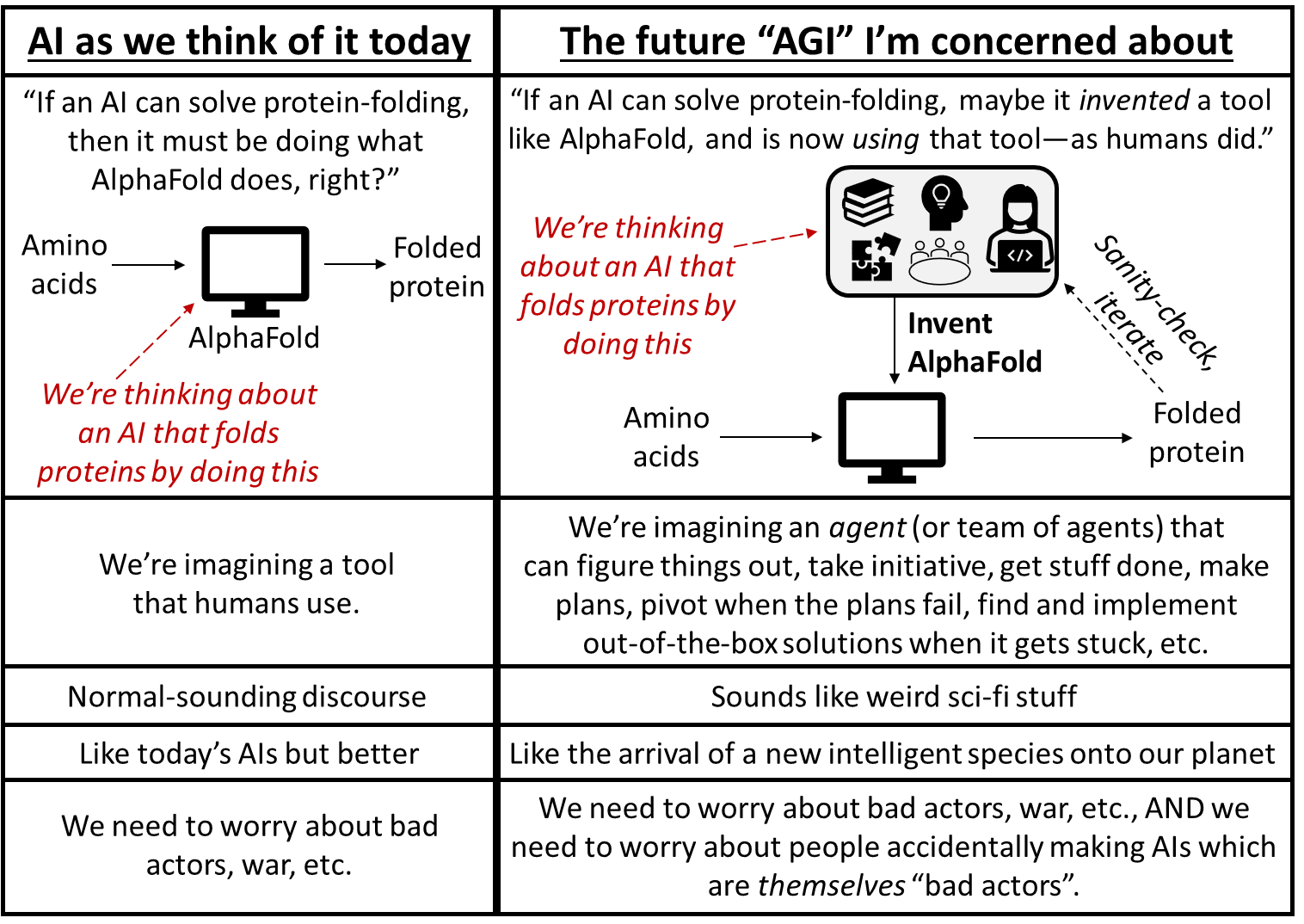

When I talk about future “Artificial General Intelligence” (AGI), what am I talking about? Here’s a handy diagram and FAQ:

“Are you saying that ChatGPT is a right-column thing?” No. Definitely not. I think the right-column thing does not currently exist. That’s why I said “future”! I am also not making any claims here about how soon it will happen, although see discussion in Section A here.

“Do you really expect researchers to try to build right-column AIs? Is there demand for it? Wouldn’t consumers / end-users strongly prefer to have left-column AIs?” For one thing, imagine an AI where you can give it seed capital and ask it to go found a new company, and it does so, just as skillfully as Earth’s most competent and experienced remote-only human CEO. And you can repeat this millions of times in parallel with millions of copies of this AI, and each copy costs $0.10/hour to run. You think nobody wants to have an AI that can do that? Really?? And also, just look around. Plenty of AI researchers and companies are trying to make this vision happen as we speak—and have been for decades. So maybe you-in-particular don’t want this vision to happen, but evidently many other people do, and they sure aren’t asking you for permission.

“If the right-column AIs don’t exist, why are we even talking about them? Won’t there be plenty of warning before they exist and are widespread and potentially powerful? Why can’t we deal with that situation when it actually arises?” First of all, exactly what will this alleged warning look like, and exactly how many years will we have following that warning, and how on earth are you so confident about any of this? Second of all … “we”? Who exactly is “we”, and what do you think “we” will do, and how do you know? By analogy, it’s very easy to say that “we” will simply stop emitting CO2 when climate change becomes a sufficiently obvious and immediate problem. And yet, here we are. Anyway, if you want the transition to a world of right-column AIs to go well (or to not happen in the first place), there’s already plenty of work that we can and should be doing right now, even before those AIs exist. Twiddling our thumbs and kicking the can down the road is crazy.

“The right column sounds like weird sci-fi stuff. Am I really supposed to take it seriously?” Yes it sounds like weird sci-fi stuff. And so did heavier-than-air flight in 1800. Sometimes things sound like sci-fi and happen anyway. In this case, the idea that future algorithms running on silicon chips will be able to do all the things that human brains can do—including inventing new science & tech from scratch, collaborating at civilization-scale, piloting teleoperated robots with great skill after very little practice, etc.—is not only a plausible idea but (I claim) almost certainly true. Human brains do not work by some magic forever beyond the reach of science.

“So what?” Well, I want everyone to be on the same page that this is a big friggin’ deal—an upcoming transition whose consequences for the world are much much bigger than the invention of the internet, or even the industrial revolution. A separate question is what (if anything) we ought to do with that information. Are there laws we should pass? Is there technical research we should do? I don’t think the answers are obvious, although I sure have plenty of opinions. That’s all outside the scope of this little post though.