This piece starts with a summary of when we should expect transformative AI to be developed, based on the multiple angles covered previously in the series. I think this is useful, even if you've read all of the previous pieces, but if you'd like to skip it, click here.

I then address the question: "Why isn't there a robust expert consensus on this topic, and what does that mean for us?"

I estimate that there is more than a 10% chance we'll see transformative AI within 15 years (by 2036); a ~50% chance we'll see it within 40 years (by 2060); and a ~2/3 chance we'll see it this century (by 2100).

(By "transformative AI," I mean "AI powerful enough to bring us into a new, qualitatively different future." I specifically focus on what I'm calling PASTA: AI systems that can essentially automate all of the human activities needed to speed up scientific and technological advancement. I've argued that PASTA could be sufficient to make this the most important century, via the potential for a productivity explosion as well as risks from misaligned AI.)

This is my overall conclusion based on a number of technical reports approaching AI forecasting from different angles - many of them produced by Open Philanthropy over the past few years as we've tried to develop a thorough picture of transformative AI forecasting to inform our longtermist grantmaking.

Here's a one-table summary of the different angles on forecasting transformative AI that I've discussed, with links to more detailed discussion in previous posts as well as to underlying technical reports:

| Forecasting angle | Key in-depth pieces (abbreviated titles) | My takeaways |

| Probability estimates for transformative AI | ||

| Expert survey. What do AI researchers expect? | Evidence from AI Experts | Expert survey implies1 a ~20% probability by 2036; ~50% probability by 2060; ~70% probability by 2100. Slightly differently phrased questions (posed to a minority of respondents) have much later estimates. |

| Biological anchors framework. Based on the usual patterns in how much "AI training" costs, how much would it cost to train an AI model as big as a human brain to perform the hardest tasks humans do? And when will this be cheap enough that we can expect someone to do it? | Bio Anchors, drawing on Brain Computation | >10% probability by 2036; ~50% chance by 2055; ~80% chance by 2100. |

| Angles on the burden of proof | ||

| It's unlikely that any given century would be the "most important" one. (More) | Hinge; Response to Hinge | We have many reasons to think this century is a "special" one before looking at the details of AI. Many have been covered in previous pieces; another is covered in the next row. |

| What would you forecast about transformative AI timelines, based only on basic information about (a) how many years people have been trying to build transformative AI; (b) how much they've "invested" in it (in terms of the number of AI researchers and the amount of computation used by them); (c) whether they've done it yet (so far, they haven't)? (More) | Semi-informative Priors | Central estimates: 8% by 2036; 13% by 2060; 20% by 2100.2 In my view, this report highlights that the history of AI is short, investment in AI is increasing rapidly, and so we shouldn't be too surprised if transformative AI is developed soon. |

| Based on analysis of economic models and economic history, how likely is 'explosive growth' - defined as >30% annual growth in the world economy - by 2100? Is this far enough outside of what's "normal" that we should doubt the conclusion? (More) | Explosive Growth, Human Trajectory | Human Trajectory projects the past forward, implying explosive growth by 2043-2065.

Explosive Growth concludes: "I find that economic considerations don’t provide a good reason to dismiss the possibility of TAI being developed in this century. In fact, there is a plausible economic perspective from which sufficiently advanced AI systems are expected to cause explosive growth." |

| "How have people predicted AI ... in the past, and should we adjust our own views today to correct for patterns we can observe in earlier predictions? ... We’ve encountered the view that AI has been prone to repeated over-hype in the past, and that we should therefore expect that today’s projections are likely to be over-optimistic." (More) | Past AI Forecasts | "The peak of AI hype seems to have been from 1956-1973. Still, the hype implied by some of the best-known AI predictions from this period is commonly exaggerated." |

Having considered the above, I expect some readers to still feel a sense of unease. Even if they think my arguments make sense, they may be wondering: if this is true, why isn't it more widely discussed and accepted? What's the state of expert opinion?

My summary of the state of expert opinion at this time is:

- The claims I'm making do not contradict any particular expert consensus. (In fact, the probabilities I've given aren't too far off from what AI researchers seem to predict, as shown in the first row.) But there are some signs they aren't thinking too hard about the matter.

- The Open Philanthropy technical reports I've relied on have had significant external expert review. Machine learning researchers reviewed Bio Anchors; neuroscientists reviewed Brain Computation; economists reviewed Explosive Growth; academics focused on relevant topics in uncertainty and/or probability reviewed Semi-informative Priors.2 (Some of these reviews had significant points of disagreement, but none of these points seemed to be cases where the reports contradicted a clear consensus of experts or literature.)

- But there is also no active, robust expert consensus supporting claims like "There's at least a 10% chance of transformative AI by 2036" or "There's a good chance we're in the most important century for humanity," the way that there is supporting e.g. the need to take action against climate change.

Ultimately, my claims are about topics that simply have no "field" of experts devoted to studying them. That, in and of itself, is a scary fact, and something that I hope will eventually change.

But should we be willing to act on the "most important century" hypothesis in the meantime?

Below, I'll discuss:

- What an "AI forecasting field" might look like.

- A "skeptical view" that says today's discussions around these topics are too small, homogeneous and insular (which I agree with) - and that we therefore shouldn't act on the "most important century" hypothesis until there is a mature, robust field (which I don't).

- Why I think we should take the hypothesis seriously in the meantime, until and unless such a field develops:

- We don't have time to wait for a robust expert consensus.

- If there are good rebuttals out there - or potential future experts who could develop such rebuttals - we haven't found them yet. The more seriously the hypothesis gets taken, the more likely such rebuttals are to appear. (Aka the Cunningham's Law theory: "the best way to get a right answer is to post a wrong answer.")

- I think that consistently insisting on a robust expert consensus is a dangerous reasoning pattern. In my view, it's OK to be at some risk of self-delusion and insularity, in exchange for doing the right thing when it counts most.

What kind of expertise is AI forecasting expertise?

Questions analyzed in the technical reports listed above include:

- Are AI capabilities getting more impressive over time? (AI, history of AI)

- How can we compare AI models to animal/human brains? (AI, neuroscience)

- How can we compare AI capabilities to animals' capabilities? (AI, ethology)

- How can we estimate the expense of training a large AI system for a difficult task, based on information we have about training past AI systems? (AI, curve-fitting)

- How can we make a minimal-information estimate about transformative AI, based only on how many years/researchers/dollars have gone into the field so far? (Philosophy, probability)

- How likely is explosive economic growth this century, based on theory and historical trends? (Growth economics, economic history)

- What has "AI hype" been like in the past? (History)

When talking about wider implications of transformative AI for the "most important century," I've also discussed things like "How feasible are digital people and establishing space settlements throughout the galaxy?" These topics touch physics, neuroscience, engineering, philosophy of mind, and more.

There's no obvious job or credential that makes someone an expert on the question of when we can expect transformative AI, or the question of whether we're in the most important century.

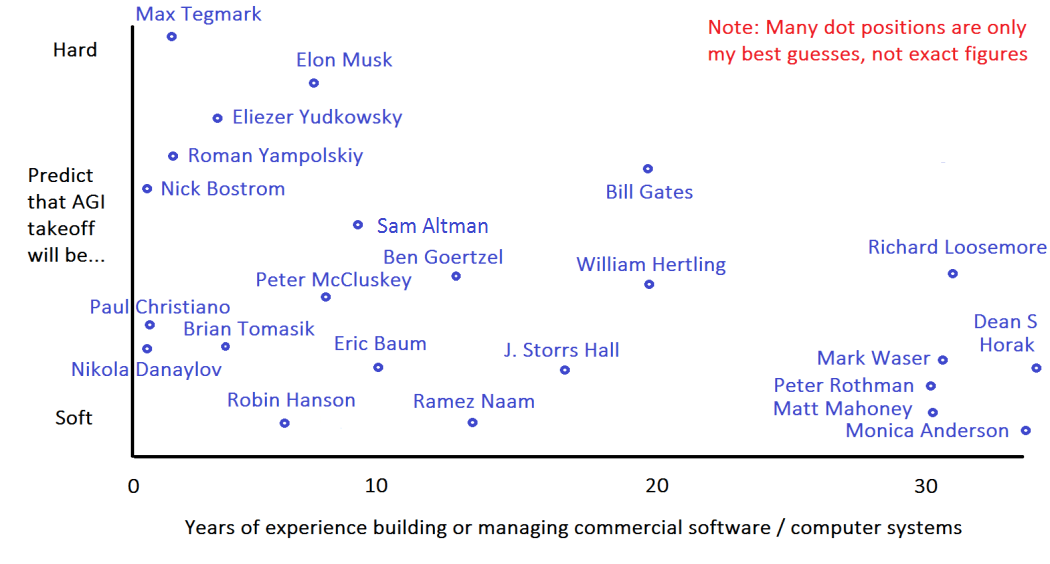

(I particularly would disagree with any claim that we should be relying exclusively on AI researchers for these forecasts. In addition to the fact that they don't seem to be thinking very hard about the topic, I think that relying on people who specialize in building ever-more powerful AI models to tell us when transformative AI might come is like relying on solar energy R&D companies - or oil extraction companies, depending on how you look at it - to forecast carbon emissions and climate change. They certainly have part of the picture. But forecasting is a distinct activity from innovating or building state-of-the-art systems.)

And I'm not even sure these questions have the right shape for an academic field. Trying to forecast transformative AI, or determine the odds that we're in the most important century, seems:

- More similar to the FiveThirtyEight election model ("Who's going to win the election?") than to academic political science ("How do governments and constituents interact?");

- More similar to trading financial markets ("Is this price going up or down in the future?") than to academic economics ("Why do recessions exist?");3

- More similar to GiveWell's research ("Which charity will help people the most, per dollar?") than to academic development economics ("What causes poverty and what can reduce it?")4

That is, it's not clear to me what a natural "institutional home" for expertise on transformative AI forecasting, and the "most important century," would look like. But it seems fair to say there aren't large, robust institutions dedicated to this sort of question today.

How should we act in the absence of a robust expert consensus?

The skeptical view

Lacking a robust expert consensus, I expect some (really, most) people will be skeptical no matter what arguments are presented.

Here's a version of a very general skeptical reaction I have a fair amount of empathy for:

- This is all just too wild.

- You're making an over-the-top claim about living in the most important century. This pattern-matches to self-delusion.

- You've argued that the burden of proof shouldn't be so high, because there are lots of ways in which we live in a remarkable and unstable time. But ... I don't trust myself to assess those claims, or your claims about AI, or really anything on these wild topics.

- I'm worried by how few people seem to be engaging these arguments. About how small, homogeneous and insular the discussion seems to be. Overall, this feels more like a story smart people are telling themselves - with lots of charts and numbers to rationalize it - about their place in history. It doesn't feel "real."

- So call me back when there's a mature field of perhaps hundreds or thousands of experts, critiquing and assessing each other, and they've reached the same sort of consensus that we see for climate change.

I see how you could feel this way, and I've felt this way myself at times - especially on points #1-#4. But I'll give three reasons that point #5 doesn't seem right.

Reason 1: we don't have time to wait for a robust expert consensus

I worry that the arrival of transformative AI could play out as a kind of slow-motion, higher-stakes version of the COVID-19 pandemic. The case for expecting something big to happen is there, if you look at the best information and analyses available today. But the situation is broadly unfamiliar; it doesn't fit into patterns that our institutions regularly handle. And every extra year of action is valuable.

You could also think of it as a sped-up version of the dynamic with climate change. Imagine if greenhouse gas emissions had only started to rise recently5 (instead of in the mid-1800s), and if there were no established field of climate science. It would be a really bad idea to wait decades for a field to emerge, before seeking to reduce emissions.

Reason 2: Cunningham's Law ("the best way to get a right answer is to post a wrong answer") may be our best hope for finding the flaw in these arguments

I'm serious, though.

Several years ago, some colleagues and I suspected that the "most important century" hypothesis could be true. But before acting on it too much, we wanted to see whether we could find fatal flaws in it.

One way of interpreting our actions over the last few years is as if we were doing everything we could to learn that the hypothesis is wrong.

First, we tried talking to people about the key arguments - AI researchers, economists, etc. But:

- We had vague ideas of the arguments in this series (mostly or perhaps entirely picked up from other people). We weren't able to state them with good crispness and specificity.

- There were a lot of key factual points that we thought would probably check out,6 but hadn't nailed down and couldn't present for critique.

- Overall, we couldn't even really articulate enough of a concrete case to give the others a fair chance to shoot it down.

So we put a lot of work into creating technical reports on many of the key arguments. (These are now public, and included in the table at the top of this piece.) This put us in position to publish the arguments, and potentially encounter fatal counterarguments.

Then, we commissioned external expert reviews.7

Speaking only for my own views, the "most important century" hypothesis seems to have survived all of this. Indeed, having examined the many angles and gotten more into the details, I believe it more strongly than before.

But let's say that this is just because the real experts - people we haven't found yet, with devastating counterarguments - find the whole thing so silly that they're not bothering to engage. Or, let's say that there are people out there today who could someday become experts on these topics, and knock these arguments down. What could we do to bring this about?

The best answer I've come up with is: "If this hypothesis became better-known, more widely accepted, and more influential, it would get more critical scrutiny."

This series is an attempted step in that direction - to move toward broader credibility for the "most important century" hypothesis. This would be a good thing if the hypothesis were true; it also seems like the best next step if my only goal were to challenge my beliefs and learn that it is false.

Of course, I'm not saying to accept or promote the "most important century" hypothesis if it doesn't seem correct to you. But I think that if your only reservation is about the lack of robust consensus, continuing to ignore the situation seems odd. If people behaved this way generally (ignoring any hypothesis not backed by a robust consensus), I'm not sure I see how any hypothesis - including true ones - would go from fringe to accepted.

Reason 3: skepticism this general seems like a bad idea

Back when I was focused on GiveWell, people would occasionally say something along the lines of: "You know, you can't hold every argument to the standard that GiveWell holds its top charities to - seeking randomized controlled trials, robust empirical data, etc. Some of the best opportunities to do good will be the ones that are less obvious - so this standard risks ruling out some of your biggest potential opportunities to have impact."

I think this is right. I think it's important to check one's general approach to reasoning and evidentiary standards and ask: "What are some scenarios in which my approach fails, and in which I'd really prefer that it succeed?" In my view, it's OK to be at some risk of self-delusion and insularity, in exchange for doing the right thing when it counts most.

I think the lack of a robust expert consensus - and concerns about self-delusion and insularity - provide good reason to dig hard on the "most important century" hypothesis, rather than accepting it immediately. To ask where there might be an undiscovered flaw, to look for some bias toward inflating our own importance, to research the most questionable-seeming parts of the argument, etc.

But if you've investigated the matter as much as is reasonable/practical for you - and haven't found a flaw other than considerations like "There's no robust expert consensus" and "I'm worried about self-delusion and insularity" - then I think writing off the hypothesis is the sort of thing that essentially guarantees you won't be among the earlier people to notice and act on a tremendously important issue, if the opportunity arises. I think that's too much of a sacrifice, in terms of giving up potential opportunities to do a lot of good.

-

Technically, these probabilities are for “human-level machine intelligence.” In general, this chart simplifies matters by presenting one unified set of probabilities. In general, all of these probabilities refer to something at least as capable as PASTA, so they directionally should be underestimates of the probability of PASTA (though I don't think this is a major issue). ↩

-

Reviews of Bio Anchors are here; reviews of Explosive Growth are here; reviews of Semi-informative Priors are here. Brain Computation was reviewed at an earlier time when we hadn't designed the process to result in publishing reviews, but over 20 conversations with experts that informed the report are available here. Human Trajectory hasn't been reviewed, although a lot of its analysis and conclusions feature in Explosive Growth, which has been. ↩

-

The academic fields are quite broad, and I'm just giving example questions that they tackle. ↩

-

Though climate science is an example of an academic field that invests a lot in forecasting the future. ↩

-

The field of AI has existed since 1956, but it's only in the last decade or so that machine learning models have started to get within range of the size of insect brains and perform well on relatively difficult tasks. ↩

-

Often, we were simply going off of our impressions of what others who had thought about the topic a lot thought. ↩

-

Reviews of Bio Anchors are here; reviews of Explosive Growth are here; reviews of Semi-informative Priors are here. Brain Computation was reviewed at an earlier time when we hadn't designed the process to result in publishing reviews, but over 20 conversations with experts that informed the report are available here. Human Trajectory hasn't been reviewed, although a lot of its analysis and conclusions feature in Explosive Growth, which has been. ↩

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

There seems to be a new expert survey of 2022 here: 2022 Expert Survey on Progress in AI – AI Impacts

( I am a beginner in AI, so correct me if I am wrong....)