TLDR: Just pick up the phone. Agree on permissions for information before you share it (see Step 4).

I have worked as a professional journalist covering AI for over a year, and during that time, multiple people working in AI safety have asked me for advice on engaging with journalists. At this point, I've converged on some core lessons, so I figured I should share them more widely.

I've also reviewed some of the prior art about how to talk to journalists on LessWrong and found it unsatisfying. The answer to the question often seems to be "Don't."[1]

Unsurprisingly then, I think many people feel like they are not prepared to talk to journalists. They often have a sense that they are waiting to receive some arcane knowledge that would equip them for such a treacherous conversation, the sort of knowledge acquired at ritual ceremonies called "media trainings."

In fact, there is very little such secret knowledge. It's easy to talk to journalists—it mostly involves picking up the phone—and the most important lessons can fit in a quick post. This post provides those lessons so you no longer have any excuses for not talking to journalists if you want to, which I think you should.

In the interests of keeping this to a practical how-to guide, I've sketched my brief case for why you might want to talk to these unlovely creatures in a companion post: Why Talk to Journalists.

Before the Call

Step 1: Understand the Interaction

How you should approach your first call with a journalist depends on the context of the interaction.[2] Here are five common scenarios, each of which would call for different strategies on your part.

- You are contacting a journalist because you want them to write about you and your work. For example, you want coverage for your research or your startup.

- A journalist is contacting you because you are a domain expert.

- You are contacting a journalist because you want to leak sensitive information.

- A journalist is contacting you because you might have privileged information.

- You're casually talking to a journalist at a social event.

Your first job is to identify what kind of interaction you're in, so you can work backwards to figure out your goals. For the first two situations, you almost always want to talk on the record, if you're going to talk to the journalist at all. (I'll explain what on the record means in a moment.) The last three situations require more discernment.

Step 2: Research Your Target

It can help you prepare if you know a little bit about the journalist, especially if you're trying to choose someone to offer a potential story.

What kind of publication do they write for? If it's a business publication, they'll ask questions about business models, revenue numbers, funding rounds, and valuations. If it's a tech publication, they'll ask questions about the tech. And so on.

What kind of articles do they write? Are they good takes or bad takes? Do they seem to have experience in the subject matter? Do they break news, or do they just provide commentary about news that's already public? If they break news, you can expect them to be nosier, but also better at handling sensitive information.

Step 3: Sus Out the Topics

If you'd like, you can ask ahead of time what kinds of questions the journalist would like to discuss. It's unlikely they'll give you a full list of questions (they probably haven't come up with them yet), but they can probably give you a sense of the topics they have in mind.

Step 4: Set Permissions

This is probably the single most important step of the process. You can also do it at the start of the call, but some people prefer to get it out of the way beforehand, to reduce potential awkwardness or miscommunications during the call.

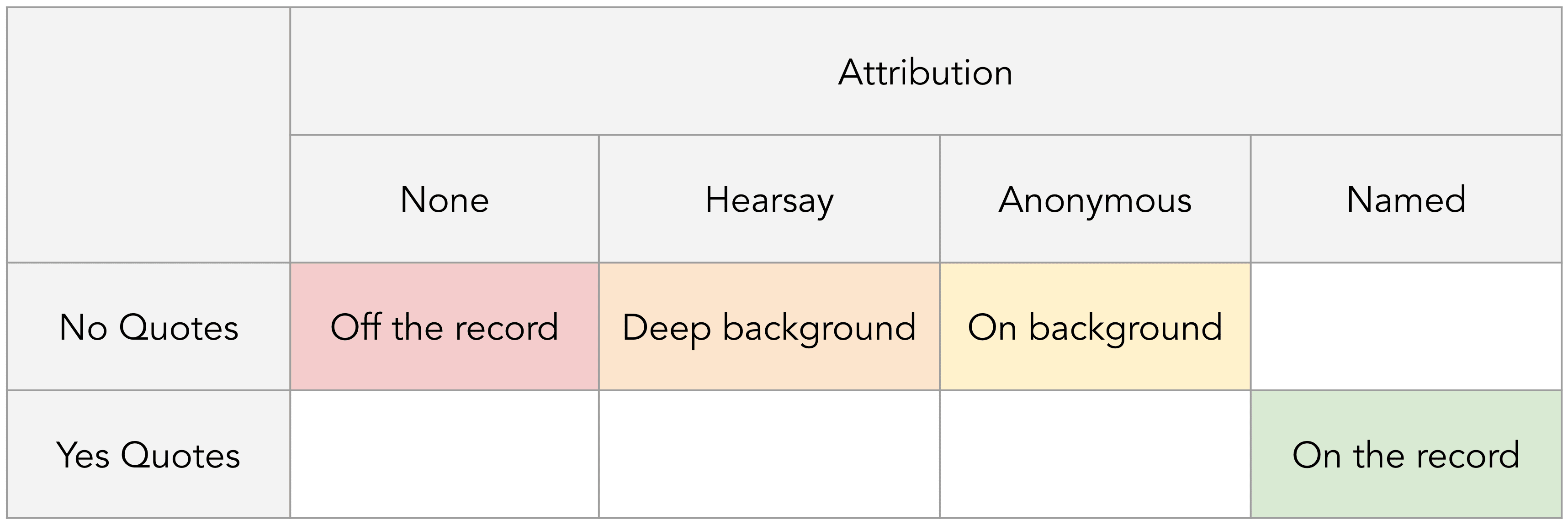

The most common permissions are on the record, off the record, and on background.[3] But these are horrible terms with lots of ambiguity. I strongly recommend you taboo these terms and instead disambiguate them into two questions:

- Who will you attribute the information to?

- Specifically, will I be named or anonymous? If anonymous, what attribution will you use?

- Will you quote me or paraphrase?

Resist the urge to sound like you know what you're doing by using the jargon! But for reference, this is what those terms typically mean:

Until you agree otherwise, everything you say is on the record by default (I guess because the First Amendment gives journalists the right to publish whatever they want and they have used this strong negotiating position to set up the industry norms in a way that is favorable to them.)

The key word is "agree." You have to get the journalist's agreement that you're talking off the record etc before you share your information (as Lindesy Halligan learned the hard way).[4] Likewise, you should push for the permissions you want. This is a negotiation, and you're allowed to bargain.

Of course, if a journalist shares your information against your wishes because of a technicality like they hadn't agreed to the permissions yet, they know they are burning their relationship with you. It's just that their professional reputation will stay mostly intact because they followed the letter of the industry norms.

Those norms are not legally binding. The fact that journalists will honor your agreement is just enforced by professional reputation. But typically journalists won't jeopardize their careers.

Changing Permissions

You can change the permissions as many times as you would like during the course of a conversation, but it's wise to get agreement each time.

You can even change permissions after the call, but it's not as common. For example, you might have a call on background but tell the journalist you might be willing to go on the record for specific points afterwards.[5] (I've never seen permissions go the other direction and get stricter after the call, but I would bet it's happened.)

Similarly, you can start with the agreement that the journalist will only paraphrase your points, but they can ask about including specific quotes afterwards. This is called quote approval and some publications don't allow it.

On Background

On background is your friend. It's a great balance between allowing you to speak candidly while still influencing the journalist's coverage. If you get taken out of context or say something dumb, your name won't be attached to it.

You can also agree on a particular attribution. The more specific the attribution, the more credible you will be to readers, but the less anonymous you will be.

Here are some common attributions:

- Someone familiar with the matter (probably the broadest possible attribution)

- Someone with knowledge of the matter

- Someone with direct knowledge

- An employee at the company

- A current/former employee

- A researcher at the company

- An executive at the company

- An investor in the company

- Someone who spoke with the executive

- Someone who was in the room during the talks

- Someone who viewed the document

- A spokesperson for the company

It's worth nailing down the particular attribution when you decide on permissions so the journalist doesn't inadvertently de-anonymize you by picking the wrong one.

You'll notice that many of these attributions make clear how the source knows. Even if you agree on a vague attribution, a good journalist will still ask you about the source of your own information. It's not that they doubt you, they're just doing their due diligence. If you don't have direct knowledge, you probably can't be used as a source anyway. That should make you feel more free to share rumors that you only know secondhand because they will only get printed if the journalist finds direct sources to corroborate.

Deep Background

This one's uncommon, and I recommend you avoid it. The idea is that the journalist can use the information, but not attributed to a specific person, or even their organization.

So the information might appear in an article cited to "word on the street" or "some people are saying." It might appear without an attribution at all.

Really the only time this is helpful is if a journalist is new to a topic and you want to help them understand the context so they don't embarrass themselves. For example, if you want to explain the difference between pretraining and posttraining to someone who hasn't written about AI before. It's not off the record because there's an understanding they might use the information, but it's broad context that doesn't need to be attributed to a particular person.

Off The Record

Off the record is kind of worthless to both sides (making matters worse, often when sources say it they actually mean on background.) For the journalist, it can be a waste of time because they can't directly use anything from the conversation. And for the source, saying something off the record still makes it more likely the information gets published, compared to saying nothing at all. That' s because the journalist can confirm your tips with other sources, then attribute the information to them instead.

One situation in which you might want to talk off the record is if you are okay being an anonymous source but you don't want to be the only one. Some publications require multiple sources anyway, but others make exceptions. You might talk off the record initially, but say that you are willing to go on background if the journalist gets another source.

Anonymity

Note, however, that these permissions apply only to what the journalist can publish. They do not govern what the journalist can share with other individuals. If you want to make sure the journalist does not tell anyone that you spoke, you have to additionally specify that.

Of course, journalists will also exercise discretion in these interpersonal settings, just like everyone does on a daily basis. You don't have to worry that the journalist will drop your name the next time they talk to your boss, for example.

In fact, journalists go out of their way to obscure the identities of their sources. For example, a journalist might avoid public LinkedIn connections with their sources.

Journalists and editors even diligently protect the identities of sources within newsrooms. Many editors will not ask journalists to reveal the names of their sources.

Embargoes

Journalists can agree to embargoed news, meaning they won't write about what you tell them until after a specific date and time. This is most relevant if you're trying to get coverage for an upcoming announcement.

If you're offering the embargoed news to only one publication, that's called an exclusive, and journalists tend to like that because it means readers will click on their article first when they look up the news. You can also sweeten the deal by offering the publication a temporary monopoly on the news (don't call it that though). It's fairly common to offer 30 minutes to 2 hours of exclusivity. Whether to offer an exclusive or try to cast a wide net with your embargoed news is a strategy question that depends on the circumstances.

As with other permissions, make sure to get the journalist's agreement first. For embargoes, the journalist might need to seek permission from their editor before agreeing.

Step 5: Figure Out Key Points

On the call, you might be surprised if the journalist seems smarter and more knowledgeable than their previous articles had led you to believe.[6] Don't let your guard down! Even if the journalist understands you perfectly, important details can get lost in the game of telephone between you, the journalist, and their editors.

It's also hard to make corrections after the article is published, so you want to avoid misunderstandings as early as possible.

To minimize the loss of those important details as your interview gets compressed into an article, you should determine ahead of time the 1-3 most important points you would like to get across during the call. Come up with simple analogies to explain them.

It's also worth figuring out if there are any topics you don't want to discuss, so you don't get caught off guard if they come up on the call. It's hard to anticipate all possible lines of questioning, so don't worry about being comprehensive.

During the Call

Step 6: Be Nosy

Journalists are very nosy; they have to be. In conversations with normal people, there's a shared understanding of what questions would be inappropriate to ask. And you can politely nudge your conversation partner away from topics you don't want to discuss.

Journalists will plow right ahead and ask intrusive questions. Remember, these are the same people who ask Trump to his face about the Epstein Files and ask the Prince of Saudi Arabia about approving Khashoggi's assassination.

The nosiness can feel aggressive, but most times, it's just that the journalist is desensitized to the potential rudeness: They're used to PR people screaming at them on the phone and lying to them. Plus, the journalist is probably uncalibrated on what counts as sensitive information in your life. For example, what counts as IP varies from company to company.

One implication is that you should be nosy back! Here are some questions you are allowed to ask:

- What's the angle for your piece?

- Who else are you talking to?

- What have you heard so far?

- Do you know when the article is coming out?

These questions will give you a better sense of the journalist's intentions and how your interview fits in, which can help you tailor your answers. They can also help you figure out if you've been trapped in some kind of bad-faith hit piece. (More on that in Step 8.)

Step 7: Hammer Your Key Points

Remember to get across your key points by the end of the call, even if they don't really respond to the questions the journalist asks you. It's worth repeating your point a couple different ways, and it can help to ask the journalist questions about your points to check their understanding.

In TV interviews, you have very little time to get across your message, so you might want to take a page from the politicians' book and use the A B C D technique. From Google overview:

A - Address: Acknowledge and answer the question asked by the interviewer.

B - Bridge: Use a transition phrase to connect their question to your key message. For example, you could say, "That's an interesting point, and it's related to...".

C - Communicate: Clearly state your key message. This should be a concise and compelling statement you want the audience to remember.

D - Develop: Expand on your key message with supporting details, evidence, or anecdotes to make it more impactful and complete.

But this is best-suited for live interviews, it's probably too uncooperative to use in typical interviews.

Step 8: Defense Against the Dark Arts

Again, journalists are nosy, and that can feel aggressive, but most of the time, the journalist is not actually trying to trap you, they might just be ignorant that a topic is sensitive. So if you get asked about a topic you don't want to discuss, such as the off-limits points you identified in Step 5, just say that you don't want to talk about it.

An explicit refusal will be more effective than subtly trying to evade the question. For example, you can say, "I'm afraid I don't have anything more to say on this at the moment, but we might put out a post soon that goes into more detail." Or more bluntly: "No comment."

More generally, you should get some reassurance from the fact that you are probably not calibrated on what kinds of information are considered newsworthy. On multiple occasions, I've been interviewing someone who suddenly asks in hushed tones if we can go off the record, just to share something like "in my opinion, this university's approach to robotics software architecture is not as promising as it once was." A point that I could never convince my editor to print even if I wanted to!

Journalists are very busy. Unless your information directly fits into their coverage, they probably won't be interested. That means that if you do let slip some unrelated detail of your opinions, or your research, or how your organization works, it's unlikely to get printed. Most of the time, you're just not that important. Security through obscurity. (And again, if you don't have direct knowledge, the journalist probably couldn't turn around and print it anyway.)

But journalists do have a bag of tricks that are reserved for the highest-stakes interviews. These dark arts might come out, for instance, if a journalist has an important tip they're trying to confirm, you're one of the only people in the world who can confirm it, and they only have 10 minutes on the phone with you. On the off chance you do find yourself in such an interview, here are two techniques to watch out for:

- Bluffing: Journalists might make it sound like they know more about the topic than they do so you inadvertently confirm their information. For example, they might ask leading questions like "why do you think the CEO fired them?" to confirm that a company had layoffs.

- Repeated Questions: If you deflect a question the first time around, they might ask it again in a different way a few minutes later. Like nosiness, it's a subtle violation of conversational norms.

If all else fails, you can always hang up.

After the Call

Step 9: Follow Up

You can check in about when the article will be published, you can send points that occur to you later, you can link to references that you mentioned on the call, etc.

You can also give feedback once the article comes out (but keep in mind what I said above that journalists and editors hate making corrections.)

Step 10: Keep in Touch

Some of the benefits of talking to journalists require a sustained relationship, so feel free to stay in contact.

If you send them occasional tips, they will try to reciprocate. If you give them scoops, you will be their favorite person in the world.

You probably shouldn't worry that you're messaging them too often; their whole job is badgering people to talk to them. It's not like dating, where there's etiquette about how long you should wait to text them or whatever.

What's Next

For you: What are you waiting for? Go call a journalist! I hope I've made it clear that the game has simple rules, and some basic strategies can take you quite far. It can also be fun to play!

For me: I have two more posts planned for this sequence.

- Newsroom Epistemics: The strange psychology, sociology, epistemology, and incentives of news publications.

- How to Get News Coverage: The techniques I've seen from the best PR people to get their clients in the news.

- ^

Consider this excerpt from Nathan Young's Advice for Journalists:

Currently I deal with journalists like a cross between hostile witnesses and demonic lawyers. . . . I talk to lawyers only after invoking complex magics (the phrases I’ve mentioned) to stop them taking my information and spreading it without my permission.

I actually agree with most of the issues Nathan identifies, I just think the balance of considerations still favors engaging with journalists.

- ^

It probably will be a call. Many journalists prefer to talking on the phone or Zoom over email or text.

- ^

To be clear, I'm calling these "permissions" for the sake of a handle to refer to

them, but that's not a standard industry term that other journalists would recognize. - ^

If you accidentally let slip something you shouldn't have, you can ask to change the permissions for it afterwards. "Actually, I think I'll have more to say on that soon, but could we keep that point off the record for now?"

- ^

Some publications follow a rule that the same source cannot be attributed on background and on the record in the same article, which can complicate things. But that's a problem for the journalist to sort out, not you.

- ^

The causes of that gap are a subject for a future post.