This post is about space governance macrostrategy. I've found the model I present very valuable for thinking about space governance and I'm confident in the overall message, but I expect to refine these ideas a lot.

TL:DR: There are three distinct windows in which a single actor could take control of the long-term trajectory of human civilisation:

- control of Earth (using AI or self-replication)

- control of the Solar System (using a Dyson swarm)

- control of the galaxy (first-mover interstellar expansion).

I argue that stages 1 and 2 dominate, and competition progressing to stage 3 is a failure mode of human civilisation as it leads to conflict, squandered resources, galactic x-risks and s-risks. Interventions to positively influence the long-term future through space governance are centred around affecting the outcome of the second stage of competition.

Introduction

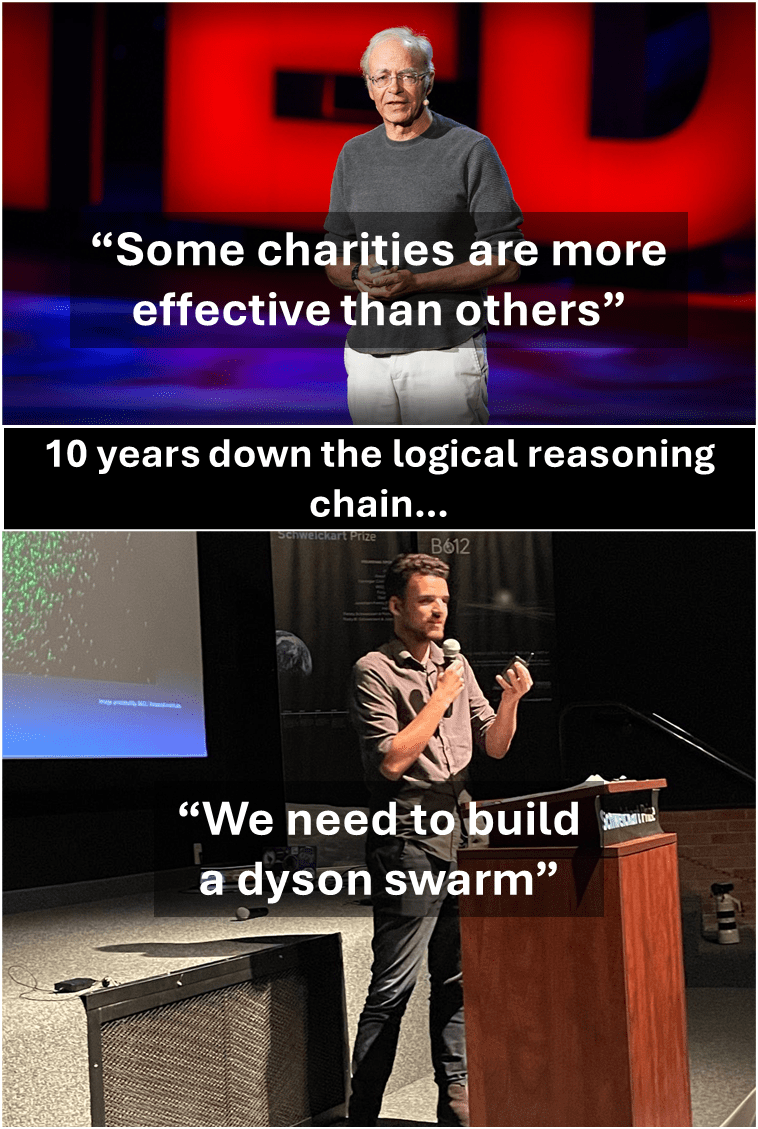

There is no clear best long-term future from a moral perspective:

- Figuring out a set of moral goals for a galactic civilisation has a lot of hard steps, like figuring out what consciousness is, developing a unifying theory of morality, and deeply understanding the universe[1]. I think the chances we successfully pass through all these hard steps is something like 10-30%, where most of the success modes involve developing aligned superintelligence and speed-running the long reflection. But, for now, setting a horizon goal for large scale space expansion risks squandering vast resources on misguided morals.

But we can work on instrumental goals towards making moral progress:

- All these hard problems prompted Toby Ord to recommend a long reflection to figure them all out before we spread to the stars[2]. The idea of being able to aim towards an instrumental goal of making progress on the hard moral questions is really useful[3]. Will MacAskill has also advocated for bootstrapping to viatopia, a state of civilisation where we have the best possible chance of reaching a near-optimal future.

So, when I think about improving the long-term future from a space governance perspective, I don't find it very helpful to think about the higher moral goal, including what present day human space expansion and eventual galactic colonisation ought to look like. However, we can think about the instrumental goals that are probably common to any spacefaring civilisation pursuing any moral goal. These instrumental goals might include existential security[4], avoiding power grabs, avoiding conflict[5], avoiding value drift, and not squandering resources[6].

I think power grabs are particularly interesting, as a power grab could occur on Earth or in the near-term in space (next 10 to 30 years) and that could affect the execution of all of the other instrumental goals forever. This makes tractability for influencing the long-term future much clearer - we needn't decide what a galactic civilisation ought to look like and somehow design policies that would last billions of years to bring that vision to reality. All we need to do is make sure some rogue actor doesn't steal the long-term trajectory of human civilisation and mess up the instrumental goals[7].

I think it's generally assumed that the long-term trajectory of human civilisation might be determined sometime shortly after the creation of superintelligence, or more accurately, based on the decisions taken during the development of AI. But that isn't necessarily the case, and in this post I examine the question: when will the long-term trajectory of human civilisation will be determined?

When is the long-term trajectory determined?

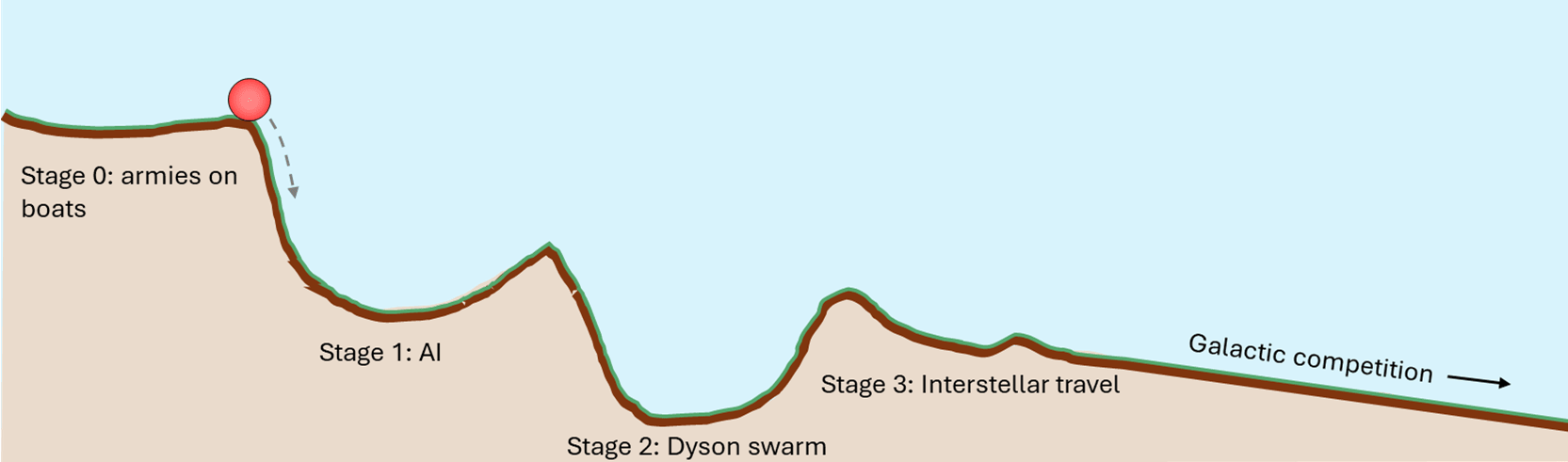

Building on ideas related to persistent path dependence and lock-in, I think the creation of AGI is the first of 3 opportunities, or stages, where an actor could set the long-term trajectory of human civilisation[8]:

- By dominance of the planet’s resources, likely through the control of the most powerful ASI, or by a mastery of self-replicating machines[9]. If not then,

- by dominance of the star system's resources through the control of a Dyson sphere, and later, star lifting[10]. If not then,

- by dominance of the galaxy’s resources through interstellar spacecraft and settlement, and later, control of the galactic centre.

This can be thought of as 3 stages of a competition, where the players compete to gain dominance in each stage. If no-one gains dominance in the first stage (i.e. competition continues), it moves to the next stage, and then the next. The dynamics change at each stage, and I want to set the terrain for each of them, discuss the key levers we might pull now, and assign a bunch of subjective probabilities to things.

Stage 1: Earth's Resources | AI and Self-replication

The potential for AI to enable lock-in has been discussed in-depth. So, briefly, there are many features of AI that lend themselves well to power grabs, including better coordination ability between AIs, removal of humans from workflows, strong first mover advantages, secret loyalties, development of powerful new technologies and weapons, improved strategic planning, immortality through digital sentience, and generally, the ability to dominate economies through optimisation, self-replication, and automation. This could allow a small group, or AI itself, to gain total hegemony on Earth and therefore control the long-term trajectory of human civilisation.

The other technology that I think is generally underappreciated (or miscategorised) as a mechanism to drive power grabs, existential risk, lock-in, and s-risk is self-replication. Self-replication is the most powerful ability that life possesses, and it has allowed life to turn a rock in space into a biosphere and a civilisation, and develop consciousness, probably creating all moral value that exists. AI could enable self-replication, but the development of self-replicating technologies are not dependent on the development of AI. The main development needed to enable self-replication is the design of machines with a lower variety of resource requirements, so that they can be replicated with less complicated resource collection[11]. On Earth, self-replication is the main driver of x-risk from nanotechnology and bio-engineered pandemics. Self-replication is also a mechanism to allow power grabs as they enable exponential productive capacity, which is key for winning in conflicts and dominating the world economy. Self-replicators are also extremely powerful weapons. Consider the mosquito as a self-replicating machine - it kills over a million humans per year incidentally and is extremely hard to defend against primarily because it replicates itself even from a very small population[12].

Self-replication is likely to really come into its own in space. But before I move on to space governance, it's important to note that space governance matters a lot less in some worlds than others. Space governance mostly matters in worlds where one of the following does not occur:

- We all go extinct.

- AI takes over the World or everyone listens to advice from an aligned benevolent superintelligence.

- A person or small group of people take over the World and don't care about other people's opinions.

This can be summarised as: space governance matters most in worlds where competition for resources and (by extension) control of the long-term future is not settled on Earth after the development of ASI and/or mature self-replication[13]. So, we move on to the next stage of the competition for the long-term future.

Stage 2: The Star | Dyson Swarms & Star Lifting

OK, so we have very powerful AI and self-replication and no global hegemony has emerged. Humanity squints and looks at the giant ball of energy in space, representing 99.8% the mass of the Solar System...

I am concerned about Dyson swarm power grabs. I think Dyson swarm construction could start some time between 2035 and 2060, mainly dependent on AGI/transformative AI timelines. Dyson swarms are just solar panels in orbit around the Sun, and they don't have to encircle the whole sun to generate many orders of magnitude more energy than all of Earth. I don't really see them as sci-fi, it just makes a lot of sense for a space economy to start using that energy. A Dyson swarm is likely to grow naturally with the space economy over time.

However, if an actor tried really hard to build one as quickly as possible, then self-replication and positive feedback loops would make the initial resource input to build one surprisingly small, and the timescale for construction of a primitive Dyson swarm surprisingly fast. Without getting into a step by step guide to power grab with a Dyson swarm[14], there are some general dynamics that are quite concerning and might lead to concentration of power.

When assessing the risk of a power grab, I think the most plausible Dyson swarm construction plan involves mining M-type or salicaceous asteroids[15], which have more than enough material, and initiating a positive feedback loop, where the mining of space resources is powered by solar captors created using the space resources. With this plan, a full Dyson swarm could be constructed within decades (definitely longer than 20 years but not as long as 60[16]). However, even just 0.1% of a Dyson swarm[17] would generate 700,000,000× more energy than Earth (this doesn't take 0.1% of the time - 0.1% of a Dyson swarm is at least 80% of the way to constructing a full Dyson swarm).

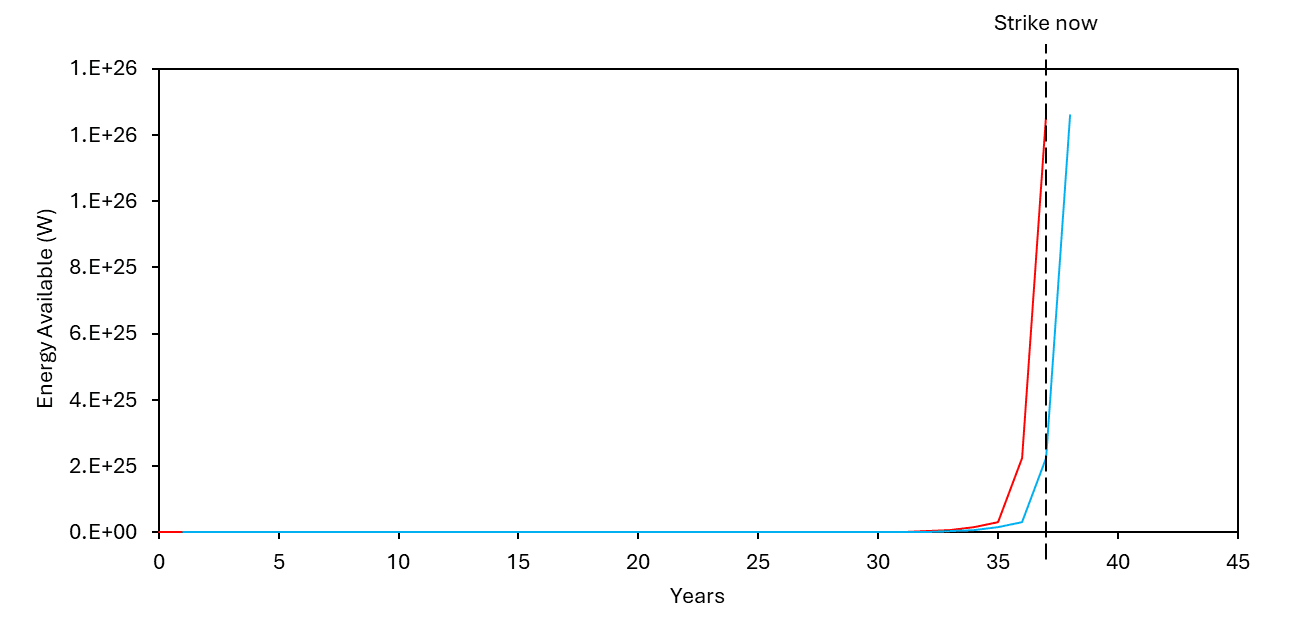

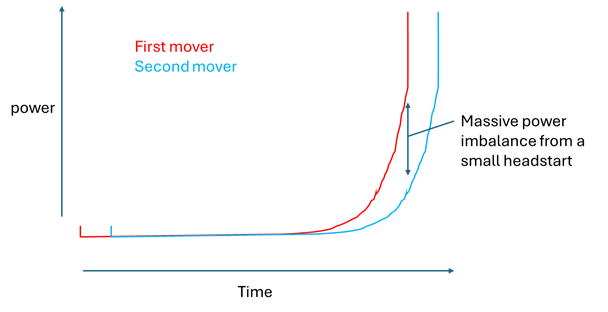

The positive feedback loop is slow to kick in, as in Stuart and Anders’ paper where they lay out a Dyson swarm building plan, 99% of the material is mined in the last 4 years over a 31 year resource collection time. So, competition to gain dominance of the star’s energy is mostly about who can get to that stage fastest. As a result, an actor could gain a massive power imbalance from just a small first mover advantage because of the positive feedback loop that kicks in at the end[18]:

Here’s Anders and Stuart’s Dyson swarm construct plan on a non-logarithmic scale (it's logarithmic in their paper), with an actor that starts their plan just 1 year later:

This results in a huge power imbalance near the end of construction, where the first mover has ~5x as much energy after ~36 years. The first mover could leverage this advantage to destroy the second mover. It's unclear exactly how, but if you have that much energy, you'd have a lot of options, including lasers and kinetic missiles.

Assuming conflict in space has been robustly outlawed, and actors just compete, the main inputs to determine success in competition are energy, tech level, and replication rate/build rate of the Dyson swarm. There is still a first mover advantage due to a few different dynamics:

Figuring out what's going on in space is really hard:

- A first mover could plausibly masquerade as an asteroid mining operation for many years. The solar captors for the Dyson swarm would be very thin (like mm thick), so if they face perpendicular to Earth, they would be essentially invisible to Earth based telescopes - it's hard enough to detect asteroids hundreds of meters across. Or, asteroids orbiting at ~1 AU on the opposite side of the Solar System from Earth could be mined for resources and turned into solar captors out of view from Earth because the Sunlight blocks the view. Even if you were in view of Earth and people knew you were making solar captors, the solar captors could stay near the asteroid for a long time and you could plausibly argue that the solar captors are just for powering the asteroid mining. I'm only about 20% sure that someone could pull off something like this, and if so, not for long. That might be enough given the huge first mover advantage explained above. Also, successful asteroid mining companies would already have a lot of infrastructure in space - so just mining asteroids gives you a strong first mover advantage in Dyson swarm construction when that begins.

Catching up is extremely costly:

- Assuming[19] the first mover launches an array of solar captors to initiate the positive feedback loop, then after 4 years of the positive feedback loop[20], their initial solar captor area is ~80x larger, and after 5 years it's ~150x larger. This multiplier represents the amount of additional initial investment for the second mover to catch up to the first mover after that amount of time. So, as a random example, if a wealthy private actor or a country invested 500 million dollars in setting off a Dyson swarm construction plan, and a second actor realised what they were doing 4 years later, they would have to invest 40 billion dollars to catch up. And the manufacturing time to build and launch $40 billion worth of solar captors might be so high that catching up might even be impossible.

It's unclear that an equilibrium emerges with multiple actors in control:

- Actors can shield others' Dyson swarms by building in front of them, closer to the Sun. This initiates a race to closer orbits, until you either reach an orbit where the cost of radiating the heat is too high, or your material melts. So, this means that the actor with the best Dyson swarm design might win out, decreasing the likelihood that we end up with multiple actors in control of the Sun's energy.

Overall, I think there is a large first mover advantage in Dyson swarm construction, and some aspects make me think that one actor could gain dominance over the energy of the Sun. However, the ability to predict strategies and competition dynamics in Dyson swarm construction is limited, especially since it will most likely happen post-ASI.

How can we influence stage 2 now?

I think that preventing power grabs is a great example of a tractable thing to do to positively influence the long-term future in space. It's quite robust to rebuttals on space governance work, like attempts to influence space policy washing out over long timescales. So, instead of trying to predict the optimal values for a spacefaring civilisation and trying to implement them now, we can aim to create the best conditions for human civilisation to decide on those values. The most obvious way to do that is to prevent one actor from stealing humanity's long-term trajectory.

Here are some interventions that I'm feeling positive about:

- Spread longtermist ideas to the space sector. The more people in the space sector who are familiar with longtermism or large scale space ethics, the higher the chances that the moral importance of large scale space expansion will be taken seriously.

- Influence policy towards inclusiveness[21] and caution in the domains that lead to Dyson swarm construction, including in-space manufacturing (especially self-replicating machines), space-based solar power, and asteroid mining. The policies and norms around Dyson swarm construction will be inherited from these domains. As it currently stands, it's completely legal to power grab with a Dyson swarm. The Parker Solar Probe is already in the Sun’s orbit collecting energy, and there have been no legal issues with this. Also, a global space solar industry is emerging with the goal of placing solar panels in Earth’s orbit and beaming energy down to the ground. Additionally, multiple companies including Karman+ and AstroForge have received tens of millions of dollars to mine asteroids, which is legal under the USA’s Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act and under the Artemis Accords[22]. Furthermore, the Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx missions have collected asteroid material, which they assumed ownership of, with little backlash. So, all the stages in Dyson swarm construction (mining resources -> building solar captors -> collecting sunlight) have legal precedent.

- Get involved in the space industry! This is similar to the strategy of working at OpenAI or Anthropic as someone concerned about AI safety. Working at the companies at the frontiers of the space domain might be a way to influence the norms that eventually emerge around Dyson swarms.

- Found a company. "OpenDysonSwarm: Our mission is to ensure that the Dyson Swarm benefits all of humanity" (that's a joke - the founding of OpenAI might turn out to be one of the worst things to happen in human history). For sure though, there are lessons to be learnt.

In this story, at which point did a Dyson swarm power grab become inevitable?

- Transformative AI is created in 2030, dramatically accelerating space capabilities, primarily through automated robotics[23].

- The USA and the international community build lunar bases. The USA's model of international space policy under the Artemis Accords wins out, securing the ability for private companies to mine, utilise, and sell space resources for a profit[24].

- An asteroid mining industry emerges, and 1 or 2 companies rise to dominate the industry and they build lots of space infrastructure (for mining and refining materials) and acquire claims (legal or physical) to large quantities of asteroids[25].

- After a while, one of those asteroid mining companies begins using the space resources to construct solar panels, which they use to power further resource collection. With that, they initiate a positive feedback loop on energy and resource collection with a lead on everyone else of about 5 years due to their resource claims and existing infrastructure[26].

- No-one can catch up due to the extreme quantities of infrastructure needed to launch into orbit and the strong positive feedback loop started by the asteroid mining companies. One or two actors come to dominate the energy of the Sun and are now in control of the long-term trajectory of human civilisation.

Star lifting

I also mentioned star lifting above. Stars do not generate a lot of energy compared to their mass. By removing the mass of a Star and reusing it (e.g. in fusion reactors), the amount of energy generated from a star can be increased by many orders of magnitude. The Sun has a huge gravity well, so you need Dyson swarm levels of energy to remove the mass in the first place. "Using 10% of the Sun's total power output would allow 5.9 × 1021 kilograms of matter to be lifted per year (0.0000003% of the Sun's total mass), or 8% of the mass of Earth's moon". A civilisation that is star lifting would make a civilisation with a Dyson swarm look pathetic.

Stage 3: The Galaxy | Interstellar Travel

OK, let's assume no actor managed to dominate the asteroid mining industry and a peaceful equilibrium emerged around the Sun, where multiple actors control vast quantities of energy. Humanity looks to the stars.

Competition for control of galactic resources

I won't spend too long on this because I know others have done some really amazing work on answering this question and I'd love to see them publish it, rather than me parrot it[27].

So, briefly, whether or not an actor (particularly a first mover) could gain control of a galaxy depends on whether they can get to most other star systems before anyone else, so the main thing to optimise for is speed. This depends on a few factors:

- Their acceleration method. With a partial Dyson swarm, there are lots of options, like using a coilgun, or laser-propelled solar sail. Rockets aren't very useful due to the rocket equation - the costs are really high.

- Their deceleration method. Spacecraft must decelerate to land on celestial bodies and use resources at their destination. This is where rockets might be useful as it would be exceptionally difficult to slow down spacecraft across a galaxy using a laser. A spacecraft might use antimatter–matter annihilation, nuclear fusion, or nuclear fission rockets.

- The cargo. Carrying humans is a lot slower. I think the faster you go, the more cosmic rays you're exposed to. Also, you'd want to go slower for safety reasons, as at extreme speeds (~0.999 c), even a collision with a dust particle could destroy the spacecraft, whereas you can send hundreds of unmanned probes without concerns about losing some of them.

- The space terrain. The cosmic dust density can vary by many orders of magnitude, so the route you take really matters. The higher the cosmic dust density, the slower the spacecraft has to go to avoid being destroyed. This is most relevant at galactic scales, not really for journeys within our star cluster.

- The defensive capabilities of the interstellar spacecraft. They could drop debris behind themselves to blow up kinetic missiles in pursuit, deploy extremely reflective shields to mitigate space laser attacks, or alter their trajectories stochastically to avoid being hit.

- Star system offense-defense balance. How long before the second mover do you need to get to a star system to be able to defend it indefinitely?

It's unclear to me whether it's possible for a first mover to get everywhere before everyone else, especially if multiple actors are controlling energy on the order of magnitude of Dyson swarms.

Dyson swarms are more important than interstellar travel

Here, I'll argue that stage 2 (Dyson swarm construction) matters much more than stage 3 (interstellar travel).

If there isn't yet a Dyson swarm and interstellar travel hasn't been attempted, then an actor attempting a power grab of other star systems would likely aim for the construction and control of a Dyson swarm first, not other star systems. With control of a primitive Dyson swarm, they could deny interstellar travel rights to others through utilisation of the Sun's energy. So, the battle to conquer the universe is more likely to be settled within the Solar System, and could be initiated by a relatively weak first mover from Earth.

To illustrate the strategic importance of a Dyson swarm, take two actors who want to conquer the universe some time around 2040 (assume we have gone through an intelligence explosion):

- Actor 1 [the Interstellar conqueror] aims to send a (totipotent) spacecraft to Alpha Centauri, where it will intercept asteroids, mine and refine materials from those asteroids, use those materials to construct solar captors in space, and then place them in heliocentric orbit around the star. This leads to a Dyson swarm. Then they will use the Dyson swarm’s energy to travel to thousands of other star systems with the goal of building more Dyson swarms, self-propagating further, and conquering and defending all stars forever.

- Actor 2 [the Sun stealer] aims to build spacecraft to intercept asteroids in the Solar System, mine and refine their materials, construct solar captors in space, and place them in heliocentric orbit around the Sun. They plan to use the Dyson swarm’s power to build and accelerate spacecraft to thousands of other star systems to build more Dyson swarms and grab the energy of the universe.

In this scenario of only two actors, I think the Sun stealer has the better strategy for galactic domination. Their strategy achieves the goal of sending probes across the galaxy sooner, is cheaper to initiate, and is less vulnerable to interference. The interstellar conqueror will not have access to a Dyson swarm to propel their spacecraft to Alpha Centauri. They could use a phased array of ground-based (or in-orbit) lasers to propel the spacecraft, as was planned for the Breakthrough Starshot mission. These lasers could also be used to decelerate the spacecraft on approach to Alpha Centauri. However, laser-propulsion could be interfered with or intercepted by the Sun stealer as they gain dominance in the Solar System. If the Sun stealer gains dominance early on, the spacecraft may not reach the desired cruising speed and will take longer to reach Alpha Centauri. Additionally, the Sun stealer could intercept the laser at a later stage, removing the spacecraft’s deceleration ability and causing it to shoot right past Alpha Centauri. So, if the interstellar conqueror (with limited resources) aims for interstellar colonisation instead of dominance in the Solar System, they would be forced to use traditional rocket engines, which are extremely costly. It’s generally considered extremely challenging to get the travel time to Alpha Centauri very far under 100 years[28]. Even using matter-antimatter engines, a proposed mission to ⅓ the distance of Alpha Centauri has a proposed duration of ~40 years[29].

So, if you want to conduct a power grab in space, an interstellar travel mission is costly and risky unless you have dominance in the Solar System first.

3 Stages of Competition: Summary and Takeaways

The 3 stages of competition can be thought of as chasms in a varied landscape. "Consider a ball rolling over a varied landscape: it might roll up and down hills, changing its speed and direction, but it would eventually settle in some chasm or valley, reaching a stable state". The ball settling into a valley represents lock-in of a particular set of values, and the 3 stages I present above represent the regions in the landscape with the deepest valleys.

So, my overall take on the 3 stages of competition for the long-term future is that stage 1 is in full swing, and it's not clear that one actor will gain global dominance. If stage 2 begins, which I think could happen any time in the next 5 to 20 years, then the race could continue to outer space. I think the long-term future might be ~70% determined in stage 1, ~30% determined in stage 2, and rounding error determined in stage 3. Lock-in is not necessarily bad, and these stages also represent opportunities to influence the long-term future and decide on values for a galactic civilisation. If we pass through all of them without doing that, then we end up with the default pathway to galactic colonisation, which I will discuss next.

If competition for Dyson swarm construction is a game of chess, the pieces are already moving: Google is working on Project Suncatcher, Sam Altman is chatting about Dyson swarms, Elon owns a space company, an AI company, and a solar panel company, and is discussing building thousands of solar-powered AI satellites. Building a Dyson swarm is currently legal. Dyson swarms are extremely important for the long-term future and they can't really be ignored by the longtermism and large scale space ethics communities anymore. One actor cannot be allowed to decide what to do with the long-term trajectory of human civilisation - that's a decision for all of humanity, or, at least, everyone who cares about that sort of thing.

This model of the 3 stages of competition for the long-term trajectory of human civilisation is the essence of my argument for the tractability of working on better futures and space governance[30]. Preventing one actor from stealing humanity's future is an essential goal to achieve a near-optimal future. I will now discuss why a global dialogue and plan for galactic civilisation is so essential.

The default pathway to galactic colonisation sucks

I'm ~90% confident in this statement: Unchecked competition over galactic resources would be a moral catastrophe and a squandering of the potential of human civilisation

So, let's assume humanity has gone through all 3 stages of competition, and no hegemony or totalitarian control has emerged on Earth or in the Solar System, and there's no clear conqueror of the galaxy. Without design from the beginning, there will be competition for the galaxy's resources by diverse actors with different moral goals, and humanity's trajectory will be disentangled. Human civilisation will learn and grow into diverse cultures across the galaxy for billions of years.

This trajectory prevents organised planning and designing of the galactic spreading of human civilisation, but galactic civilisations might need to be designed from the start because of:

- Really hard problems in morality (not totally damning - mostly good futures are still possible without optimisation for the optimal moral good)

- Really hard instrumental goals (a lot more damning - everything might be doomed)

I briefly covered the really hard problems in morality in the first section. I think it's quite clear that it's very hard to figure out what we ought to do in space. So I'll focus on the hard instrumental goals now, as many tend to assume that sending interstellar settlement missions is a morally acceptable thing to do, whereas I think it's totally rude and a moral catastrophe. It's not like I think something could go very wrong and we need to prevent anything from ever going wrong... it's more like I think absolutely everything could go catastrophically wrong and we could squander almost all moral value.

The really hard instrumental goals are:

- Avoiding conflict, and hence, large scale suffering and squandering of resources

- Long-term existential security against galactic x-risks

- Avoiding s-risks and value drift

- Dealing with aliens

Avoiding conflict

The basic thesis here is that if we don't plan a spacefaring civilisation well from the beginning, conflict between and within star systems is likely to lead to significant squandering of resources. The main reasons for this are:

- Human history is littered with conflicts, so the baseline expectation is to assume that conflict would continue as humanity expands into space.

- Star systems will be very far apart and communication will be very challenging, so we might expect values and cultures to drift significantly[31]. Spacefaring civilisations with different moral goals might have problems with each other.

- On a similar track, coordination between star systems seems really hard to figure out due to the large distances. So it seems extremely unlikely that we'd get a centralised galactic authority, unless superluminal travel becomes possible (however, I do also list superluminal travel among galactic x-risks)

(You have now read 90% of the value of this subsection. It now morphs into a rant about star system offense defense balance, and you may safely skip to the "Long-term survival" subsection)

Star system offense-defense balance has been touted as a key question around humanity's long-term future in space. And it usually goes something like "if star systems are defense dominant, then an actor could spread to other star systems and keep them. I'm 80% sure that star systems are defense dominant". I don't really like this framing. There's nothing wrong with it per se, but the more useful (and admittedly, harder to derive but who said this should be easy) metric would be a cite your estimated offense-defense ratio (e.g. "My estimate is that star systems are 5:1 defense dominant because it requires 5x more energy to shoot an interstellar projectile than to build a protective debris cloud"). What this shows is how much of a cost we expect conflict to incur on belligerents in space, and thus how likely we expect space conflicts to be. The higher the cost on the offense side of the ratio, the higher the cost of engaging in interstellar conflict, and thus, we can predict ~ what percentage of resources will be squandered on conflicts if we don't implement strong space governance from the outset.

I'm sorry this is turning into a rant about how to talk about star system offense defense balance. The second thing is: what is the conflict over? If it's between humans then it's much more likely to be offense dominant because you could shoot radiation and particles across large areas and give everyone cancer. But if we're discussing conflicts between actors attempting to control the energy of stars, it's more likely to be defense dominant because the attcker has to destroy a whole Dyson swarm. I lean towards the latter scenario, because what's the point in an attacker killing all the humans if the AI is still in control of the Dyson swarm, and thus, the defensive capabilities? It's a mutually assured destruction problem - but an interesting take from this paragraph is that AI has a huge advantage in space conflicts against biological beings.

The final thing I want to clarify about talking about star system offense defense balance is you need to state what stage of star system development you're talking about. For example:

- When a first mover reaches a star system, it's hard to imagine they'll have more than a few years of a lead on a second mover, so probably won't have set up protective debris clouds or other sophisticated defensive capabilities. Conflicts in space between spacecraft are likely to be very offense dominant, so it'll probably be a close fight depending on the power ratios. Maybe this stage of star system development lasts about 20 years, at which point a primitive Dyson swarm could be constructed by an advanced civilisation.

- Once a primitive Dyson swarm has been constructed, the dynamics change. This phase probably lasts about 100 years at minimum, because the next stage involves star lifting, which is extremely energy-intensive, even for a civilisation with a Dyson swarm.

- If a civilisation develops to a stage where they are star lifting at a large scale, then this allows them to generate many orders of magnitude more energy and spread out that energy generation across a much larger area. They would not be dependent on star systems anymore, and star system offense defense balance would become irrelevant.

OK, so now I shall embody my instructions, and share with you my opinion on star system offense defense balance. *ahem* The offense defense balance between two star systems with Dyson swarms in conflict over the energy of stars is ~1:5 in favour of defense, but I think it's plausibly as high as 1:20. This means that, if an attacker uses 100% of the Dyson swarm to launch an attack on another star system, a defender (with the same size star) only has to use 20% of their swarm to defend, and spend the other 80% on simulating happy people.

Briefly, the main reasons I think star system conflicts are defense dominant are:

- Building a debris field around a star system will generate early warnings of particle beams, electromagnetic beams, and relativistic kinetic missiles. The leading attacks are absorbed, probably with a bang, and defenders can respond during that warning time by simply moving space infrastructure (e.g. Dyson swarm solar captors) out of the way or intercepting the attacks with dust.

- The defender is able to react in real-time to attacks with resources in close proximity (stellar influx and materials), whereas the attacker must use more energy to launch an assault over interstellar distances.

- An attacker 100 light years away can observe the defender but cannot know what defenses they will have in place by the time weapons travel across interstellar distances and cannot know whether a strike successfully destroyed the target for another 100 years, by which point the defender could totally rebuild if they survive the initial strike. So, the attacker is forced to use as much energy as is necessary to ensure entire destruction of an enemy’s Dyson swarm in a first strike and combat any possible defense.

- For a technologically mature civilisation, regeneration and replacement of damaged infrastructure is probably much cheaper than sending interstellar beams or kinetic missiles. So, during an attack, a star system might just have to invest more energy into regeneration than the attacker is investing in offensive strikes.

- The attacker must conquer and keep a star system, or the conflict is not considered offense-dominant. Even if the defender is totally destroyed, they could have spacecraft outside the solar system waiting to move back in and turn the debris into a new Dyson swarm. So, to combat this, the attacker would not only have to fire extremely powerful interstellar weapons, but also send more spacecraft than the defender could possibly have (unlikely, see point 2) to win a space battle. That’s basically the definition of defense dominant.

Overall, this is good news and means that we might expect there to not be very many conflicts in outer space, and very few resources squandered on conflicts. However, if a star system does not constantly have a defense in place, they could be destroyed with no warning by an interstellar laser or particle beam. So, star systems might have to incur a "standing army resource cost" in the form of a debris field and constant surveillance, even if conflicts are highly defense dominant. So, if there is no mechanism to prevent interstellar conflicts, then lots of resources will still be squandered - but I can live with that.

Long-term survival

Survival? Of a galactic civilisation?!

There are some events that could potentially destroy many star systems, squander a large portion of a galaxy's resources, or even destroy galactic civilisation (I wrote about this in a lot more detail here - this section can be skipped if you're familiar with it). These "galactic x-risks" include:

- Vacuum decay: A bubble expands at the speed of light changing all of fundamental physics across the affectable universe.

- Memetic hazards: Similar to mindset hazards, but for spacefaring civilisations, some extremely dangerous and contagious piece of information, like a joke so funny you die, but bad enough to topple civilisations or convince them to abandon their moral goal.

- Self-replicating machines: Von-neumann probes with lasers and particle beams that spread out and consume resources, a.k.a. griefers.

- Time travel: Underappreciated x-risk – you could destroy a whole galactic civilisation before it’s created, depending on your favourite theory of time travel.

- Strange matter: A super stable form of matter that turns other matter into strange matter if they make contact. It could spread through large regions of space, but very slowly.

- Artificial superintelligence: Like self-replicating machines, this depends a lot on star system offense-defense balance, but an evil ASI somewhere else in the galaxy could destroy your star system using all of the above, even if you have an aligned ASI.

- Aliens: Use all of the above to destroy you.

- Superluminal travel: If you can travel faster than the speed of light somehow (e.g. wormholes), then you can destroy everyone in a short amount of time and there’s no defence – Oh no, a massive wormhole has opened up on my star system, guess I’ll die now.

- Unknowns: There is a very long list of constants and fundamental physics things that have to be very specific for life to exist. If any of them could be changed on a chain reaction-type event like vacuum decay, a galactic civilisation could be destroyed. Nothing jumps out as obvious though.

OK, but no one will actually create these things right? Yeah, maybe the probability is like 1 in a million star systems would do this, maybe they believe the universe has negative moral value so want to destroy it, or they attempt an extreme experiment that goes very wrong and initiates vacuum decay. Well, if you settle a billion star systems then the probability that a star system initiates one of these things becomes a lot closer to 100% than 99%. Furthermore, over long timescales, unlikely events become almost inevitable. So, creating a bunch of independent civilisations spread out across a galaxy is probably civilisational suicide.

The EA community consensus is that there's a ~25% chance that galactic x-risks are a real problem, with the main rebuttals being that all the galactic x-risks I list above are either not real or not capable of destroying a galactic civilisation. For reference, I'm about 60% sure that these galactic x-risks are real and inevitable under certain uncorrelated trajectories of large scale space expansion, and the main reason for my higher certainty is that I'm mostly concerned that the list of unknown galactic x-risks might be longer than we think.

So, if a competition and conflict expand into outer space, it's likely that many independent civilisations will emerge and the number of actors that could initiate galactic x-risks would increase exponentially. This might lead to catastrophe in the long-term.

Avoiding s-risks and value drift

The same mechanism of the inevitably of galactic x-risks due to the multiplication of independent actors also applies to s-risks. So, if we spread throughout the stars and let billions of independent civilisations do what they want, then it's a probabilistic certainty that at least some of them will do unimaginably terrible things like use a whole Dyson swarm to create digital beings living tortuous lives.

How bad you think this is really depends on your moral theory, and is very similar to the "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" philosophical thought experiment. Like pure utilitarians might accept this cost to access the cosmic endowment, but as I've passionately stated elsewhere, I do feel like we have a responsibility to prevent these moral catastrophes from ever happening.

A poll could be interesting (this assumes we can't have our cake and eat it, which I hope we actually can):

My main take here is that this is something worth really thinking hard about before we naively spread human civilisation throughout the galaxy.

Dealing with aliens

Aliens just make everything a lot more complicated. If galactic x-risks are real, aliens could initiate one, so do we have to conquer them to prevent that? If they're organised and probably won't initiate a galactic x-risk, do they have the same moral goal as us? If not, what should we do about that? What if their idea of morality is the complete opposite of ours? These are hard problems and they've been investigated in works related to the orthogonality thesis, moral trade, instrumental convergence, and the Fermi Paradox, particularly related to grabby aliens.

Rebuttals to my ultra-cautious approach

I think the strongest arguments for disagreeing with me that we need to coordinate and not allow competition and conflict to continue into the galaxy are along the lines of:

- What about mechanisms for driving progress on morals and the organisation of society? Competition and conflict have been the main drivers of this.

- Diverse cultures and societies have a lot of moral value, and preventing conflict might prevent the emergence of these diverse cultures.

- Galactic coordination is impossible or might drastically slow down progress, so we should focus on what we can achieve despite it.

- By correlating all star systems, aren't you drastically increasing the probability of a galactic authoritarian tyranny?

I acknowledge these as potential trade-offs in figuring out the optimal future under our starting conditions. But in my view, conflict over galactic resources prevents us from figuring out those trade-offs in the first place. This is similar to the debate around the long reflection, where initiating a long reflection might involve taking steps that we ought to think about in a long reflection.

Implications

An actor could seize the long-term trajectory of human civilisation on Earth (using AI or self-replication) or in the Solar System (using a Dyson swarm). If neither occurs, competition and conflict will likely continue throughout the galaxy. So, I've outlined two mainline trajectories for human civilisation in relation to competition and power:

- An actor seizes control of the long-term future on Earth or in the Solar System

- Competition and conflict continue as humanity expands beyond the Solar System

Both scenarios have trade-offs. In the first scenario where an actor seizes control of the long-term trajectory, they could have the time and ability to design a galactic civilisation from the beginning, but in expectation, will probably do something awful[32]. If competition and conflict continue beyond the Solar System, then reflection and coordination on the building of a galactic civilisation might not be possible. If that's true, then we might squander resources on conflict, potentially destroy ourselves, or create unimaginably terrible suffering. So, neither scenario is likely to lead to a near-optimal future.

The alternative scenarios include some form of achieving viatopia, where we coordinate as a global civilisation on our long-term goals, potentially enabled by superintelligent AI.

Final note

Finally, I just want to note that, if you buy the arguments in this post, then there are some uncomfortable truths and hard trade-offs. I want to make it clear that I don't currently advocate for conducting a power grab in space to achieve galactic coordination or thwarting certain space activities due to abstract concerns. There's a lot of progress to be made on mapping this all out in the longtermist space governance world and coming up with models for specific interventions that best balance the trade-offs. In the meantime, there are a lot of great interventions that relate to broad risk factors for a bad long-term future, like promoting longtermism within the space sector, ensuring space policies are more inclusive, understanding how AI interacts with space activities, and promoting caution in outer space activities.

Acknowledgements

Most of the ideas presented here did not originate in my brain. I am very grateful for conversations on these topics with Aviel Parrack, Toby Ord, James Giammona, Matt Allcock, Anders Sandberg, and Fin Moorhouse, and for comments on the draft from Aviel Parrack. This does not imply endorsement and all errors are my own.

- ^

Which involves answering questions with important context on our goals, like:

- Was the universe created and are we in a simulation?

- Are there aliens?

- What are the fundamental limits on technology and resource acquisition?

- ^

Robin Hanson has argued that the long reflection might be a bit dystopian and not really work in practice[33], but his alternatives are not clearly better. In my opinion, although a long reflection might be hard, it might also be necessary to achieve a near-optimal future, so we should try to solve the issues, not disregard the idea. Like developing a mechanism to speed run the long reflection using ASI or bootstrapping to viatopia.

- ^

Pursuing instrumental goals toward deep moral progress is related to the idea of instrumental convergence, which is the hypothetical tendency for beings with different moral goals to pursue very similar sub-goals like survival and resource acquisition.

- ^

Existential security is very relevant to a spacefaring civilisation. I argue that here but I'll also briefly summarise that argument in this post.

- ^

not necessarily competition, but definitely conflict.

- ^

There are some exceptions, like maybe freedom is so important that we'd be willing to allow vast quantities of resources to be squandered. Or diverse cultures and ideas are so morally valuable that the occasional conflict is acceptable. The near-optimal future doesn't mean everything is perfect as it will probably involve trade-offs unless it turns out we should just plate the universe in hedonic tiles.

- ^

However, it's important to note that, the goal is not to prevent anyone gaining power of the long-term future. An actor or group taking control of the long-term trajectory of human civilisation is inevitable eventually, whether it be a rogue actor, a country, an international coalition, longtermists, or AI. It's about influencing that towards broad factors that seem in line with viatopia, for example, ensuring the dialogue is global, high quality, thoughtful, and well-intentioned.

I think this is super important but its in a footnote to keep the post on topic.

- ^

This categorisation comes with all the caveats that every categorisation comes with: it's probably more like a scale, they blend into each other etc.

But this division has precedent with the Kardashev scale, which is based on a fundamental grouping of mass into planets, stars, and galaxies. If I was being silly about it I might group it like: Atoms, molecules, minerals, rocks, planets, stars, star clusters, galaxies, galaxy groups, and the cosmic web.

Planets, stars, and galaxies are the ones most relevant to power grabs.

- ^

I think self-replication is super important as the key dynamic that enables the industrial explosion or total dominance in conflict. Self-replication could plausibly be reached without ASI.

- ^

Star lifting is the idea of removing the mass of a star to use it for energy generation. You get way higher energy production levels this way. Like many orders of magnitude.

- ^

Trees replicate themselves completely and they're made of wood!

(that's a joke)

- ^

This is also true for diseases, of course.

- ^

An exception might be if an actor takes over the World but they're open to advice. Having a plan ready for what to do with the universe when they get to the stage of interstellar travel from a longtermist perspective might be very high leverage.

This scenario is quite unlikely though, as "the sorts of power-seeking actors who are likely to end up as global dictators are more likely to have dark tetrad traits — sadism, narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy". di Redazione, ‘Psychopathology of Dictators’; Goldman, ‘The Psychology of Dictatorship’

- ^

That one is remaining in a google doc, ready to deploy :D

- ^

Depends on the type of Dyson swarm you want to make. The main ones are:

- Mirrors, for power beaming or concentrating sunlight. The mirrors could concentrate sunlight on water containers to make Dyson swarm powered steam engines. Mirrors are best made with reflective metals like aluminium and maybe iron.

- Photovoltaics, for direct electrical generation. They need silicon which you can get from asteroids, but also a range of other materials.

- ^

Anders and Stuart estimate 31 years to deconstruct Mercury. This is unrealistic in my opinion (understatement) and not relevant to power grabs.

- ^

at 33% efficiency

- ^

This dynamic also seems to apply to the intelligence explosion.

- ^

Based on private calculations. I'm being cautious about info hazards

- ^

Based on a 4-year construction time for solar captors.

- ^

By that I mean:

- Sharing the benefits from space resources

- Including less powerful nations in space activities and in decision-making and space policy and norms

- ^

Asteroid mining is not legal under certain regimes, and many argue that the Outer Space Treaty outlaws space mining. e.g. "outer space is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means"

- ^

https://ai-2027.com/

https://www.forethought.org/research/preparing-for-the-intelligence-explosion - ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

I am very grateful for conversations with Aviel Parrack and Toby Ord about this.

- ^

Heller, René, and Michael Hippke. "Deceleration of high-velocity interstellar photon sails into bound orbits at α Centauri." The Astrophysical Journal Letters 835.2 (2017): L32.

- ^

Jackson, Gerald P. "Deceleration of Exoplanet Missions Utilizing Scarce Antimatter." Acta Astronautica 197 (2022): 380-386.

- ^

I strongly echo arguments made in the "Persistent Path-Dependence" essay arguing for the tractability of working on better futures.

- ^

building on arguments made by Daniel Deudney

- ^

They just stole the Sun. Probably not a nice person.

- ^

The argument here as I understand it is that the long reflection could be a type of lock-in risk. If we implement a world government to prevent interstellar travel, that might be extremely stable and civilisation could stagnate. Also, whether or not to create a world government and prevent interstellar travel seems like the type of thing we might want to think about in a long reflection. It's tricky.

I don't understand where your confidence re Dyson swarm construction times is coming from. Definitely more than 20 years? Why? Not longer than 60? Why?

This is quite a large range, but yeah I get that this comes out of nowhere. The range I cite is based on a few things:

So yeah, good point, that Dyson swarm construction time is not well justified within the post, and the timeline I cite should be taken as just the subjective opinion of someone who's spent a decent amount of time researching it.

OK, thanks. My vague recollection is that A&S were making conservative guesses about the time needed to disassemble mercury, I forget the details. But mercury is 10^23 kg roughly, so e.g. a 10^9 kg starting colony would need to grow 14 OOMs bigger, which it could totally do in much less than 20 years if its doubling time is much less than a year. E.g. if it has a one-month doubling time, then the disassembly of Mercury could take like 4 years. (this ignores constraints like heat dissipation to be clear... though perhaps those can be ignored, if we are disassembling diverse cold asteroids instead)

I don't think it's infohazardous at all fwiw. This is part of a more general disagreement I have with your model of Stage 2 competition. I think you are right that dyson swarms are where the action is at, but I think that your framing is off. The exponential graph to think about is not the dyson swarm construction graph in particular, but the "Economic Might" graph more generally. If tech exists to build a dyson swarm by having self-replicating industry in space, then presumably the tech also exists to have self-replicating industry on earth, and basically everyone who has that tech will be in a race to boom their economies as fast as possible or else fall behind and face a huge disadvantage. A one-year gap in getting started will indeed be decisive, which is why there won't be such a gap between factions that have the requisite technology (they won't want to wait a whole year to start growing exponentially, that would be like the USA deciding to just... not grow their own economy for a whole century...)

Thanks for this comment, very useful feedback.

In A&S' paper, they assume a 5 year construction time for solar captors, which is essentially the doubling time. That is actually extremely conservative, especially if we're considering post-AGI robotics. I imagine the construction time from asteroid material to solar captors might be on the order of days to weeks, but I definitely want to look into that. Great point. There might be other fundamental constraints though. The rate limiting factor is probably more likely to be a rare material required for something like onboard computers, or argon for ion thrusters, something like that.

I think the comparison to economic might is interesting. But a weaker actor on Earth trailing far behind the leading economic power could initiate Dyson swarm construction and overtake the leader with either a huge investment or a lead time. It's not so much that they would wait around, but that they would change their strategy from building economic might on Earth to power generation in space[1]. In the end, if it's the long-term future that has the most moral value, then the most important strategic outcome is who has control of that future. All the economic might of Earth cannot compete with a Dyson swarm[2], so the Dyson swarm owner has control of the future. Economic might on Earth should be seen as instrumental to providing an advantage in stage 2 competition or denying access to stage 2 competition by winning stage 1 on Earth.

I think one nation could get away with this if:

The Sun is 99.8% the mass of the Solar System. All the energy is there.

Aside from sheer power, I think a huge intelligence advantage on Earth could win out against a Dyson swarm. Like if I was controlling a Dyson swarm with AGI but there was an ASI on Earth, I would be scared. But I wouldn't be worried about Earth's economic might.

I'm more confused by how this apparent near future, current world resource base timeline interacts with the idea that this Dyson swarm is achieved clandestinely (I agree with your sentiment the "disassemble Mercury within 31 years" scenario is even more unlikely, though close to Mercury is a much better location for a Dyson swarm). Most of the stuff in the tech tree doesn't exist yet and the entities working on it are separate and funding-starved: the relationship between entities writing papers about ISRU or designing rectenna for power transmission and an autonomous self-replicating deep space construction facility capable of acquiring unassailable dominance of the asteroid belt within a year is akin to the relationship between a medieval blacksmith and a gigafactory. You could close that gap more quickly with an larger-than-Apollo-scale joined up research endeavour, but that's the opposite of discreet.

Stuff like the challenges of transmitting power/data over planetary distances and the constant battle against natural factors like ionizing radiation don't exactly point towards permanent dominance by a single actor either.

Is the threat model for stages one and two the same as the one in my post on whether one country can outgrow the rest of the world?

That post just looks at the basic economic forces driving super-exponential growth and argues that they would lead an actor that starts with more than half of resources, and doesn't trade, to gain a larger and larger fraction of world output.

I can't tell from this post whether there are dynamics that are specific to settling the solar system in Stage II that feed into the first-mover advantage or whether it's just simple super-exponential growth.

My current guess is that there are so many orders of magnitude for growth on Earth that super-exp growth would lead to a decisive strategic advantage without even going to space. If that's right (which it might not be), then it's unclear that stage two adds that much.

Thanks Tom, yeah the threat model for stage two is quite similar to your post, where I'm expecting one actor to potentially outgrow the rest of the world by grabbing space resources. However, I do think there might be dynamics in space that feed into a first mover advantage, like Fin's recent post about shutting off space access to other actors, or some way to get to resources first and defend them (not sure about this yet), or just initiating an industrial explosion in space before anyone else (which maybe pays off in the long-term because Earth eventually reaches a limit or slows down in growth compared to Dyson swarm construction).

As for the threat model of stage 1, I don't have strong opinions on whether a decisive strategic advantage on Earth is more likely to be achieved with superexponential growth or conflict, though your post is very compelling in favour of the former.

I'm thinking about this sort of thing at the moment in terms of ~what percentage of worlds a decisive strategic advantage is achieved on Earth vs in space, which informs how important space governance work is. I find the 3 stages of competition model to be useful to figure that out. It's not clear to me that Earth obviously dominates and I am open to stage 2 actually not mattering very much, but I want to map out strategies here.

I do already think that stage 3 doesn't matter very much, but I include it as a stage because I may be in a minority view in believing this, e.g. Will and Fin imply that races to other star systems are important in "Preparing for an Intelligence Explosion", which I think is an opinion based on works by Anders Sandberg and Toby Ord.

Love this as a lock-in diagram.

Years ago when I was working with Richard Fisher on The Long View, we were trying to come up with a good extended metaphor for lock-in. I was pretty stuck on the idea of a tilt-maze (which is intuitive but unfortunately the term means little to people reading).

The problem with the tilt maze is that it is binary - you are either totally free to move the ball wherever, or you are trapped in a hole. Your diagram works much better - it intuitively gives you the idea of more and less sticky troughs. You could also represent a more binary lock in with a deeper valley.

I really enjoyed reading this post; thanks for writing it. I think it's important to take space colonization seriously and shift into "near mode" given that, as you say, the first entity to start a Dyson Swarm has a high chance to get DSA if it isn't already decided by AGI, and it's probably only 10-35 years away.