In a fiery, though somewhat stilted speech with long pauses for translation, Javier Milei delivered this final message to a cheering crowd at the Conservative Political Action Conference last week:

Don't let socialism advance. Don't endorse regulations. Don't endorse the idea of market failure. Don't allow the advance of the murderous agenda. And don't let the siren calls of social justice woo you.

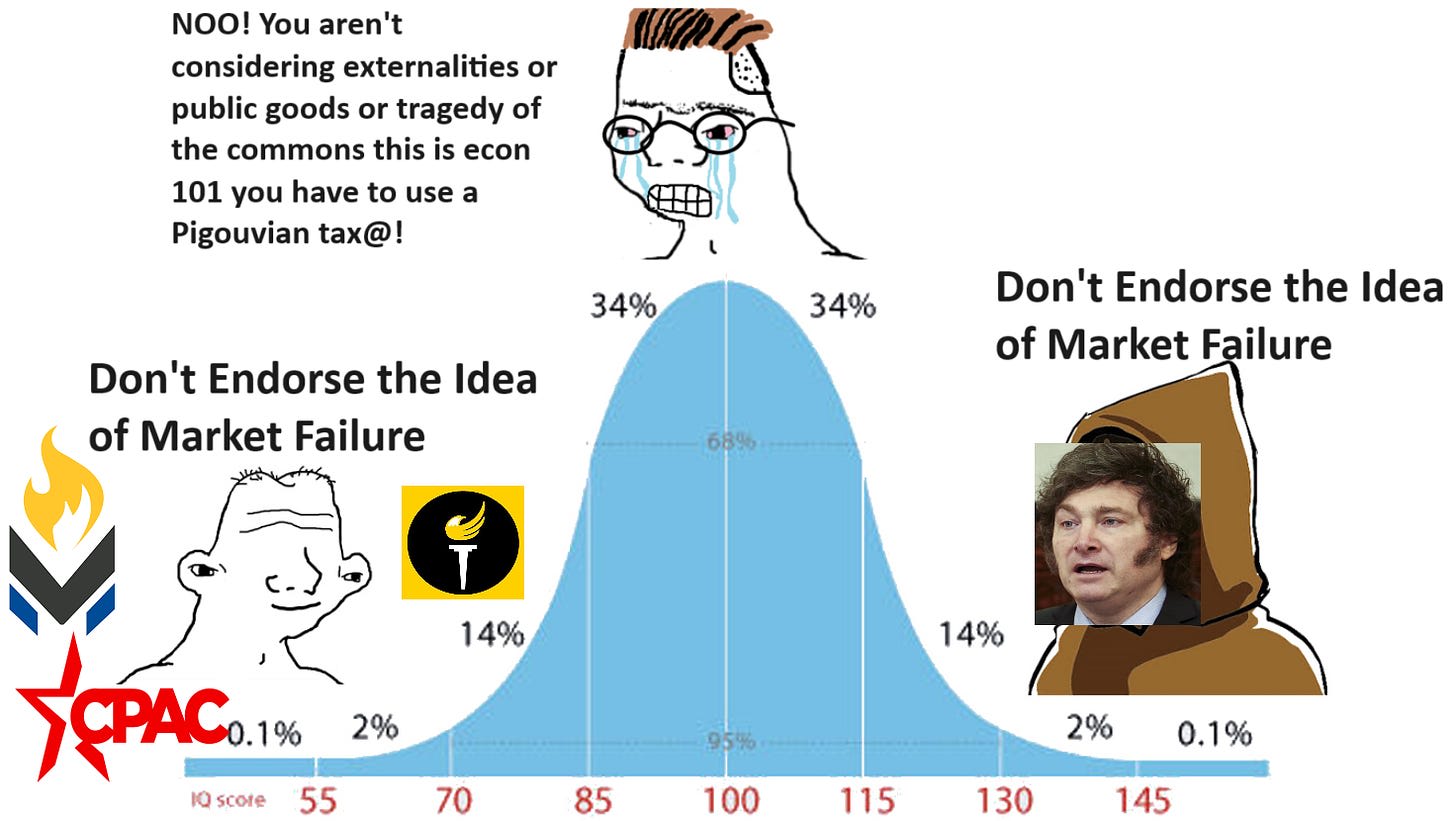

The reactions on econ twitter were unsurprisingly less positive than the CPAC crowd about calls to boycott market failure, one of the most well established facts in economics. James Medlock, for example, begs libertarians to get a step past econ 101.

The people cheering in the crowd and self-righteously quote tweeting on X are cheering for the wrong reasons. Medlock is correct that these credulous fans need to get a grip on the basics before they start denying established economic theories.

Milei, on the other hand, is an accomplished academic economist. Far from an infallible group, but we can be confident that he understands the concept of market failure well, and he’s right that we should treat it with suspicion.

What is the idea of market failure?

Market failures arise when a decision maker does not account for some costs or benefits that accrue to others. A West Virginia coal plant, for example, only considers the cost of fuel and electricity, not the cost of air pollution which accrues to people living in the surrounding mountain hollers.

In situations like this, West Virginians would be willing to pay coal mines to produce less and save them from the smog, but it is too costly to coordinate as a large group. These coordination frictions sully the conclusions of the fundamental theorems of welfare economics and drain value from the economy.

This is an uncontroversial example of the phenomenon of market failure, but the idea of market failure is more susceptible to motte-and-bailey strategies.

Here is the most common and easily defensible motte: Define “the idea of market failure” to be the claim that markets are not perfect; that there are > 0 market failures. This claim is true, and anyone who denies it plants themselves on the far left side of the mid-wit meme.

There are imperfections in every market and there are many markets with massive externalities. All the econ 101 examples are correct. Pollution, traffic, science and invention all impose costs and benefits that are difficult to trade onto people who are difficult to transact with. It is important to identify and understand these failures.

But when market failure is taught in econ classes or wielded in policy, the idea reclaims the bailey: markets are not perfect, therefore governments are capable of consistently improving them using taxes, subsidies, rules and regulations. The concept of market failure is never taught without using it to study and justify government intervention in markets, implicitly or explicitly defining the government as a “social welfare maximizer.”

It is this idea, that the imperfection of markets is easily improved by government intervention, that Milei is imploring us not to endorse.

Governments don’t automatically care about market failures

Lets return to our mountain town in West Virginia. We know there’s a market failure here: too much coal burning and too much of the smog it produces. On our econ homework we would call for a tax on coal producers to add the social cost of pollution into the coal plant’s optimization problem.

But look at West Virginia in the real world. They are full of coal plants pumping out ash without any extra tax bill. In fact, the coal industry in West Virginia is subsidized and protected by the state. All economists agree that coal plants have massive negative externalities that could be corrected with an optimal tax. Governments have lots of control over energy production and taxes, more than enough to implement this correction. Instead, they use their control to protect and expand the coal industry at deadly expense to many West Virginians.

This isn’t at all unique to West Virginia. The US doesn’t have a carbon tax. The German Green party shuts down its nuclear power plants in favor of coal. Environmental permitting regulations make it easier to frack for gas than geothermal and easier to set up offshore oil rigs than offshore wind farms. Europe and the US subsidize their fossil fuel industries.

It’s not unique to pollution or climate change either. Governments massively underfund research and development despite it being the world’s most important positive externality. Governments impose huge negative externalities across borders with tariffs and immigration restrictions. They also ignore the burden that debt places on future generations.

In general, governments are not social welfare maximizers. They are personal welfare maximizers, just like the firms involved in market failures. More accurately, they are large collections of personal welfare maximizers who are loosely aligned and constrained by lots of internal and external forces.

Some of these forces improve social welfare, like democracies expanding civil rights and avoiding famine. Others do just the opposite. Powerful lobbying by concentrated interest groups makes it profitable for legislators to spread out costs a few dollars at a time among millions of unaware voters while the benefits are concentrated a few million dollars at a time among highly motivated rent-seekers. Self-interested local governments tax or ban construction in their city as a massive negative-sum transfer from disenfranchised migrants to landholding voters. Internal bureaucratic career incentives at the FDA caused tens of thousands of deaths during the Covid-19 pandemic. Nationalism among voters and personal power seeking among leaders often makes war appealing to governments, though it is almost always negative for social welfare.

The morass of incentives and agents that make up government do not aggregate into a social welfare maximizer.

Governments are not reliable stewards of social welfare, so identifying imperfections in markets is not enough to consistently improve them. If we want governments to help us correct market failures, we need better ways to monitor, constrain, and incentivize the people inside to do so. This is the true challenge of market failure but the intellectual culture in economics too often obscures it. Once Milei’s fans (and detractors) get past econ 101, I am begging them to get started with public choice 101 before they start making policy recommendations that could easily make things worse, even in response to market failure.

Javier Milei is a politician and he is susceptible to incentives at least as much as anyone else. One of his incentives pulls towards sloganeering and shallow takes that spread quickly. “Don’t endorse the idea of market failure” can be easily interpreted as a shallow rejection of economics, which might be popular, but is false.

Still though, the automatic connection between identifying a market failure and justifying government intervention in response is worth arguing against. Governments have no inherent incentive to correct market failures and often have incentives to exacerbate them. We can and should work to improve these incentives but that can only happen after we acknowledge the serious failure of the current ones.