Sources' motivations for talking to journalists are a bit of a puzzle. On the one hand, it's helpful for journalists to work out what those motivations are, to keep sources invested in the relationship. On the other hand, sources behave in perplexing ways, for instance sharing information against their own interests, so it's often best to treat their psychology as unknowable.

Reflecting on sources' willingness to share compromising information, one mystified AI journalist told me last weekend, "no reasonable person would do this."

But to the extent I can divine their motivations, here are some reasons I think people talk to me at work:

- Bringing attention and legitimacy to themselves and their work

- Trading tips and gossip

- Steering the discourse in favorable ways

- E.g. Slandering your enemies and competitors

- Feeling in control of your life

- E.g. an employee might want to leak information to feel power over their boss

- Therapy

- A sense of obligation

- E.g. to educate the public

- E.g. to be polite when someone calls you for help

- It feels high-status

Most of these are not particularly inspiring, but if you work in AI safety, I want to appeal to your theory of change. If your theory of change relies on getting companies, policymakers, or the public to do something about AI, the media can be very helpful to you. The media is able to inform those groups about the actions you would have them take and steer them toward those decisions.

For example, news stories about GPT-4o and AI psychosis reach the public, policymakers, OpenAI investors, and OpenAI employees. Pressure from these groups can shape the company's incentives, for instance to encourage changes to OpenAI's safety practices.

More generally, talking to journalists can help raise the sanity waterline for the public conversation about AI risks.

If you are an employee at an AI lab and you could see yourself whistleblowing some day, I think it is extra valuable for you to feel comfortable talking to journalists. In my experience, safety-minded people sometimes use the possibility of being a whistleblower to license working at the labs. But in practice, whistleblowing is very difficult (a subject for a future post). If you do manage to overcome the many obstacles in your way and try to whistleblow, it would be much easier if you're not calling a journalist for the first time. Instead, get some low-stakes practice in now and establish a relationship with a journalist, so you have one fewer excuse if the time comes.

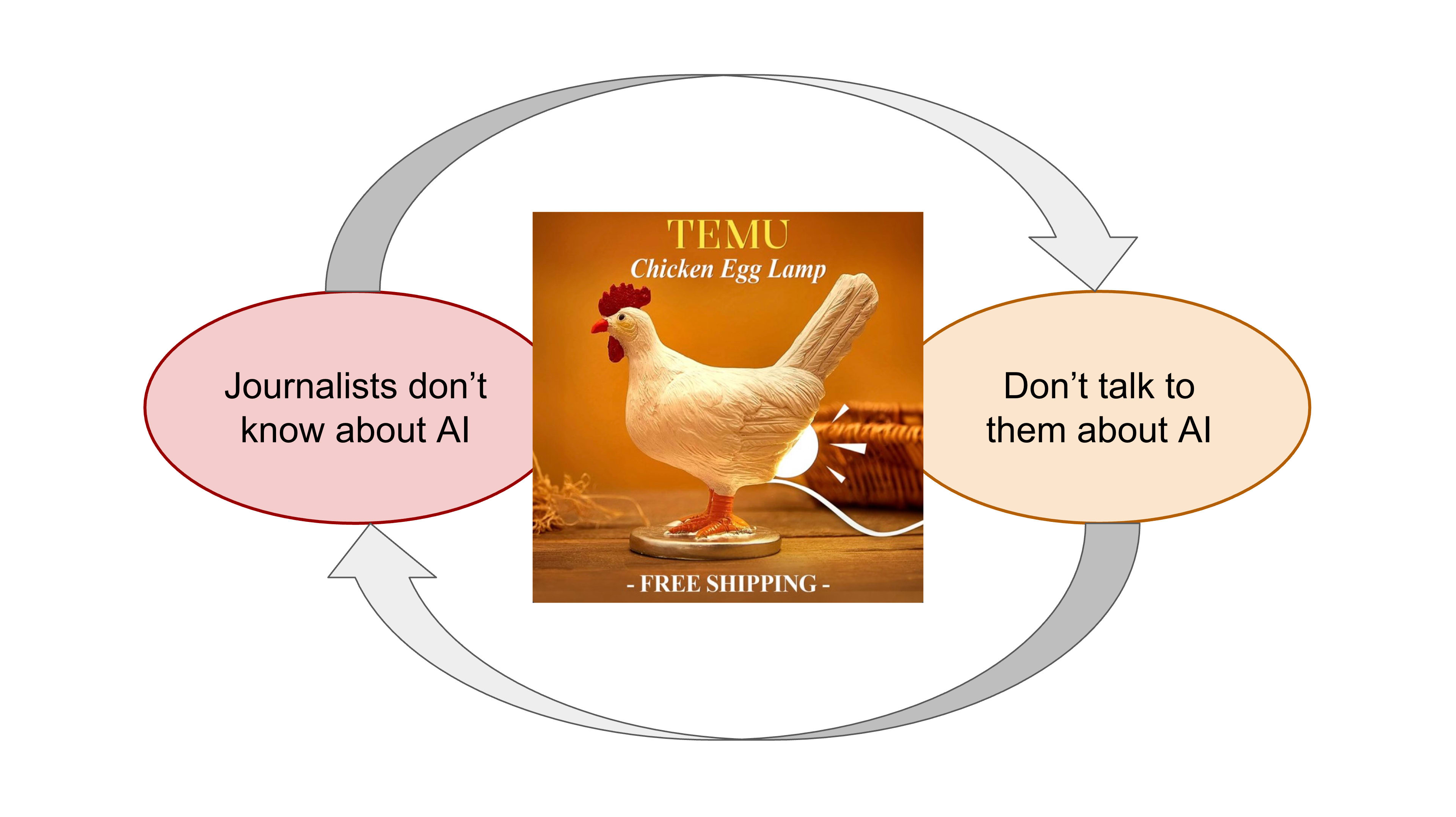

Maybe news articles offend your epistemic sensibilities because you've experienced Gell-Mann amnesia and have read too many sloppy articles. Unfortunately, I don't think we can afford to be so picky. If you don't talk to journalists, you cede the discourse to the least scrupulous sources. In this case, that's often corporate PR people at the labs, e/acc zealots, and David Sacks types. They are happy to plant misleading stories that make the safety community look bad. I think you can engage with journalists while holding to rationalist principles to only say true things.

It's pretty easy to steer articles. It often only takes one quote to connect an article on AI to existential risks, when counterfactually, the journalist wouldn't have realized the connection or had the authority to write it in their own voice. For example, take this recent CNN article on a ChatGPT suicide. Thanks to one anonymous ex-OpenAI employee, the article connected the suicide to the bigger safety picture:

One former OpenAI employee, who spoke with CNN on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation, said “the race is incredibly intense,” explaining that the top AI companies are engaged in a constant tug-of-war for relevance. “I think they’re all rushing as fast as they can to get stuff out.”

It's that easy!

Overall, it sounds disingenuous to me when people in AI don't talk to journalists because they dislike the quality of AI journalism. You can change that!

If you appreciate initiatives like Tarbell that train journalists to better understand AI, you should really like talking to journalists yourself! Getting people who are already working in AI safety to talk to journalists is even more cost-effective and scalable. Plus, you will get to steer the discourse according to your specific threat models and will enjoy the fast feedback of seeing your views appear in print.

Here are some genres of safety-relevant stories that you might want to contribute to:

- Exposing wrongdoing at AI companies

- E.g. whistleblowing about companies violating their RSPs

- Early real-world examples of risks (warning shots)

- E.g. the Las Vegas bomber who got advice from ChatGPT

- Connecting news to safety topics

- E.g. explaining why cutting CAISI would be bad

- Highlighting safety research

- E.g. explaining how scheming evals work

- Explainers about AI concepts

- These generally improve the public's AI literacy

In practice, articles tend to cut across multiple of these categories. Op-eds also deserve an honorable mention: they don't require talking to journalists in the sense I'm writing about here, but some of the best articles on AI risks have been opinion pieces.

Quick Defenses

I'll briefly preempt a common objection: you're worried that journalists are going to misquote you or take you out of context.

First, I think that's rarer than you might expect, in part because you've probably over-indexed on the Cade Metz incident. Plus, journalists hate being wrong and try to get multiple sources, as I wrote in Read More News.

Second, you can seek out experienced beat reporters who will understand you, rather than junior ones.

Third and most importantly, even if you do get misquoted, it doesn't mean talking to the journalist was net-negative, even for that particular piece and even ex-post. As annoying as it is, it might be outweighed by the value of steering the article in positive ways.

Huh? You said the idea of sources talking to journalists is perplexing, mystifying, and indicates "unknowable" psychology, but then listed one of the obvious — not perplexing, not mystifying, and eminently knowable — explanations for this behaviour, i.e., a sense of moral obligation or social responsibility.

It’s not perplexing, mystifying, or unknowable at all! You said why it happens!

I find posts like this unsettling. This is such a Machiavellian, cynical, dominance-oriented mindset — obsessed with power, obsessed with status, obsessed with advancing your own narrow self-interest. What kind of people are you hanging out with? Frank Underwood?

My experience of people is that they mostly don’t think and act in this way. Most people:

Ah yes, unfortunately journalists are very cynical in general (more on this in the upcoming newsroom epistemics post.) And rationalists are very suspicious of journalists. Together, that means my points probably sound pretty cynical/defensive. I agree with you that in practice some sources are motivated by altruistic, pro-social reasons as well.