TLDR

Lafiya distributes self-injectable contraceptives across rural northern Nigeria. This post is meant to give a review of our work in the last year, present Rethink Priorities’ updated cost-effectiveness model on our work, and highlight our plans for the upcoming 18 months.

GiveWell's recent report highlights that they consider family planning interventions highly promising, with a cost-effectiveness bar of $20 per counterfactual year of protection for a couple (CYP); that is, a year of contraception that would not have happened otherwise. According to our most recent external cost-effectiveness analysis, conducted by Rethink Priorities, Lafiya can deliver a counterfactual CYP for $8, making us more than twice as cost-effective as GiveWell’s bar. Their CEA estimates our direct delivery work to be between 35-42x as cost-effective as cash transfers. We aim to reach 500k women with family planning by 2026. Alongside our direct work, we are currently focused on strengthening the contraceptive supply chain in Nigeria, integrating more deeply with government systems, and expanding into new areas. We’re looking to close our 2026 funding gap and would love to hear from you if you want to contribute to closing it.

We previously introduced Lafiya on the EA Forum here and were incubated by Charity Entrepreneurship in 2023.

Introduction

In Nigeria, women have a 1 in 22 lifetime chance of dying from childbirth-related complications. Roughly 75,000 women in Nigeria die every year while giving birth or shortly after. The majority of these deaths are preventable with accessible family planning and maternal health care. But in rural Nigeria, only 30% of women give birth with a skilled provider present, and only 10% of women use modern contraceptives. In many places in the rural North, even fewer women use modern contraceptives (e.g. 3% in Kebbi, 3.5% in Jigawa). This means women give birth frequently (with total fertility rates in our operating states between 5.2 and 7.6 children per woman), and they are left without appropriate healthcare to plan their families or take care of their children. Despite high demand (>20% of women in the north want to use family planning) and the well-established impact of family planning, millions of women remain without access to the information and services they need to make informed choices about their health and futures. Donor exits (e.g. USAID and various other national governments) have exacerbated funding gaps. Systemic obstacles bar women from accessing services. Family planning products are frequently out of stock, and there are few trained providers who can give accurate information with due consideration of women’s concerns. This gap persists not due to low demand, but because existing supply systems face significant inefficiencies that limit consistent availability of family planning commodities at the last mile, particularly in hard-to-reach or underserved areas. Strengthening community-based distribution complements government efforts by extending reach and improving continuity of access. In Northern Nigeria, where coverage is low and demand is substantial, the opportunity to deliver cost-effective services is particularly strong.

Our users who want to learn how to self-inject and can demonstrate the correct technique receive three more doses to take home for a year of contraceptive protection

Our work

To address these access barriers in a scalable and cost-effective way, we designed an approach centred on community-based last-mile delivery. At Lafiya, we're on a mission to make contraception accessible to anyone who needs it and wants it - no matter where they live. Our approach is simple yet innovative: we train a network of dedicated female health professionals (we call them Lafiya Sisters) who are living in rural communities. Our training provides them with information to counsel women on family planning methods, and we provide them with an innovative injectable contraceptive: DMPA-SC. DMPA-SC is a locally highly sought-after contraceptive that is easy to distribute. It lasts three months, costs just $0.85 per dose, does not require a cold chain, is highly effective and has few side effects. Crucially, women can self-inject it: a health provider teaches women how to self-inject during a first visit, and subsequently gives women three doses to take home, so they can self-manage their contraception for the rest of the year. This commodity was specifically designed for remote, low-resource settings, exactly like rural Nigeria.

So why did we design our model in the way we did? To answer that question, we need to take a deeper look at the main barriers to family planning:

- Contraceptives are frequently out of stock. For example, there is a 98% stockout rate reported for DMPA-SC in Kano in March & April 2025 (NHLMIS). Other family planning programs cannot make an impact without contraceptive stock available in health facilities; demand generation and capacity building programs all depend on a functioning supply chain in order to translate into actual contraceptive use. Persistent funding gaps for family planning commodities continue to place pressure on national and state supply chains. Without sustained domestic investment, these gaps risk deepening and further limiting access at the last mile.

- Lack of trained personnel: A mix of brain drain, distrust, and poor compensation leaves Nigeria with fewer than 2 health workers per 1000 people; this proportion is worse in northern Nigeria. Health workers who are available often do not have appropriate training in family planning.

- Misconceptions: Lagging socioeconomic and educational outcomes make misconceptions about reproductive health common in Nigeria. Fears of permanent infertility and long-term side effects deter the use of contraception.

Lafiya’s model addresses all three barriers. We bring commodities directly to the point of distribution, strengthening the supply chain and ensuring stock is available continuously with our Lafiya Sisters. Training increases the number of health workers available to conduct counselling about various contraceptive methods. During their counselling, they are specifically prompted to address myths and misconceptions. We developed a digital counselling tool that provides Lafiya Sisters with personalised prompts, helping them respond to client questions and concerns in real-time with supportive, accurate information.

The Lafiya Sisters work for the government in primary health clinics, and they also go out into the field on outreach visits, reaching communities that are cut off from the current healthcare system. This works: almost half of the people we reach (46%) have never used contraception before. We now serve approximately 30,000 women per month and keep on growing our scale.

A Lafiya Sister discusses different family planning options and dispels myths about contraception with a local community of rural women

A story from the field

Hafsai (27) from Jigawa state wanted to space her pregnancies, but had no access to family planning because she lives far from the nearest clinics and cannot afford to get there. Her frequent and unplanned pregnancies made it difficult to work and care for her children. During Lafiya’s community outreach in her village, Hafsai learned about the opportunity to take DMPA-SC from the Lafiya Sister, and since she self-injected, she now has contraceptive cover for a year. Zainab says, “I used to cry when I missed my period because I knew I couldn’t handle another child. Now, I can sleep with peace of mind.” She can take care of her six children and provide for them without worrying about the future.

Hafsai and her husband in Jigawa state during one of Lafiya's outreaches

Our evolving programmatic focus

While our early focus was solely on reaching users directly, it became clear that sustainable impact required addressing broader structural bottlenecks in procurement, financing, and data visibility. In addition to our last-mile delivery work, we engage in strengthening the Nigerian health system and the contraceptive supply chain. Specifically, we have observed the following bottlenecks in the supply chain, impeding last-mile distribution:

- Inadequate financing. There is inadequate financing for commodities at scale. Nigeria is operating on a donor-driven model, with the majority of health commodities financed by large donors. Despite donor contributions, there is still a financing gap. With competing priorities, the federal government needs to make difficult decisions on where to allocate funds, based on incomplete information.

- Inaccurate demand forecasting. The government uses modelling to anticipate next year’s demand for family planning. Because forecasting is based on actual consumption and not unmet demand, stockouts are not properly accounted for in the model. This underserves high-need areas and creates a gap that Lafiya’s work explicitly addresses. This challenge is further compounded by capacity gaps among health care staff, with incomplete documentation as a result.

- Little last-mile transport. Contraceptives are transported to the last mile through existing government systems; however, last-mile distribution remains delayed, underfunded and inconsistently implemented. Moreover, there is currently no dedicated government provision for community-based distribution of contraceptives, leaving such services almost entirely dependent on donor-funded partners. There are long lead times for facility orders, significant funding gaps where rural communities draw the short straw, and a lack of trained healthcare providers with an adequate level of family planning knowledge. Lafiya’s work ensures commodities reach rural facilities and even goes one step further: Lafiya Sisters conduct outreaches into rural communities that are left behind by the current healthcare system.

Right now is a pivotal time for implementing a sustainable approach to family planning. The recent exit of USAID has highlighted the sector’s over-reliance on donors, triggering a major reset.

As a result, our work focuses on strengthening the landscape in several crucial ways:

- Matching agreements. We work collaboratively with government stakeholders to reinforce a sustainable family planning ecosystem, prioritising partnerships in states with high unmet need and demonstrable leadership commitment. Our engagement approach encourages increased domestic investment through a performance-based co-financing framework that aligns with national procurement guidelines. Over time, this approach supports a transition to full government ownership, guided by progressive cost-sharing and actual demand patterns.

- Improving quantification and forecasting. We aim to saturate specific local government areas with family planning commodities. This will enable actual usage data to become visible in national systems by making sure that every person who wants contraception can access it, allowing for a more accurate reflection of demand. This will directly influence next year’s data and increase allocations towards family planning budgets.

- Collaborating closely with the private sector to effectively respond to unmet demand. Recognising the fiscal pressures faced by the public health system and the competing demands on government budgets, Lafiya seeks to strengthen the broader ecosystem by facilitating strategic engagement with the private sector. As part of this effort, we will explore pathways to segment users, particularly experienced, returning clients who may have the capacity and willingness to pay, and refer them to appropriate private-sector channels. This approach aims to reduce the burden on the public sector, while preserving free access for those most in need and ensuring long-term sustainability of contraceptive access.

- Digital services. We are working with the Federal Government on digitising their services. This kind of digital visibility is essential: it helps the government know how many people are currently being sent away without services, which areas are underserved, and what supplies will be needed in the year ahead. Digital systems also make it easier to spot gaps, for example, where there are not enough trained health workers, or where staff may need more support to deliver services well. Technology helps ensure that limited resources are directed where they are most needed. It strengthens accountability, reduces waste, and allows the whole system to respond in a more targeted, effective way. We are recognised as an official government partner in family planning, and provide technical assistance on using digital data systems for increased monitoring. We have recently presented our findings to the Technical Working Group and have been invited to collaborate on a national digital health tool for family planning.

Klau presenting about Lafiya’s work and digital strategy at the Technical Working Group, a major coordination platform with national policymakers

Cost-effectiveness

Our approach is highly cost-effective: based on current assumptions and modelling inputs, Rethink Priorities’ CEA estimates that with our direct delivery model, we are able to cover one counterfactual year of contraception for $8 this quarter (Q3 2025). For reference, GiveWell’s recent report states that programmes providing a counterfactual year of contraception for under ~$20 could be competitive with their top charities.

Our programmatic cost for one year of contraceptive access (CYP) is $4.85. This includes contraceptive and pregnancy test procurement, Lafiya Sister stipends, field staff cost, and set-up cost & training. The majority of this cost (74%) is DMPA-SC procurement. In our current model, we directly procure the contraceptives to ensure consistent supply and expand access where it is otherwise limited. Over time, our aim is for the government to take on procurement and running costs, a shift that supports long-term sustainability. We are primarily focused on driving down programmatic costs, since these will be the primary cost at scale. In this stage of growth, we consider it justifiable to invest more into our operations and M&E to iterate our model towards the best possible version before deploying at scale. Philanthropy can fund the set-up; government can take on running costs to ensure long-term sustainability.

The benefits of family planning go beyond direct health outcomes for women - the flow-through effects on their families and communities make this intervention particularly cost-effective

Evidence for our model

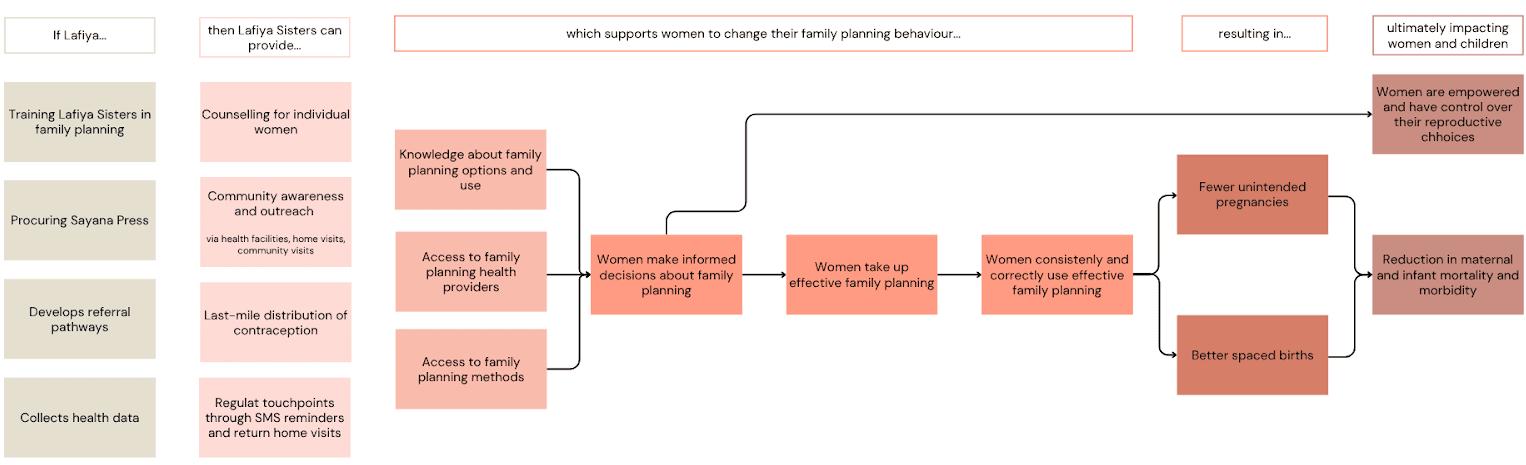

Our theory of change (below) is based on robust research conducted in the area of family planning. From literature, we see that consistent use of family planning is a highly effective method to reduce maternal deaths: an analysis of 172 countries shows that contraceptive use prevented 44% of maternal deaths, meaning the global maternal death rate would have been 1.8x as high without family planning. Women with an unmet need for contraception account for 84% of unintended pregnancies. Satisfying unmet need for family planning could lead to an additional reduction of 29% of maternal deaths.

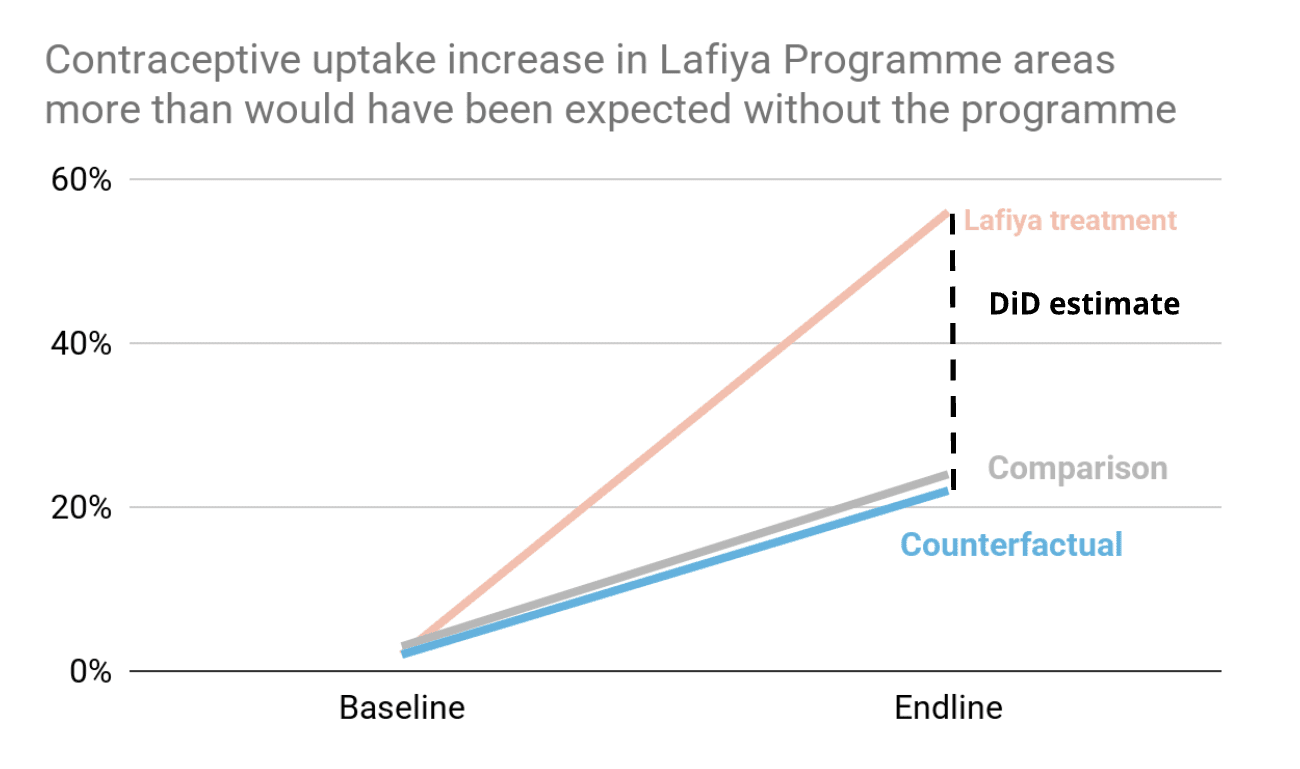

The link we were most uncertain about in our Theory of Change is whether our specific intervention effectively removes the access gaps to trained providers and contraceptives, and translates into increased contraceptive uptake. This is why earlier this year, we conducted a field study in Sokoto state. Our field study compared areas with and without Lafiya’s programme over an eight-month period (April 2024-January 2025). The main outcome: in the Lafiya programme areas, contraceptive use increased from just 2% to 56%, which is a 28x (2800%) increase from baseline. In the control areas, family planning use increased from 3% to 24%. Our model estimates that without Lafiya's intervention, contraceptive uptake in our catchment areas would have increased from 2% to 22%. This means that our programme led to a counterfactual 34 percentage points increase in contraceptive use among women, within an eight-month time frame. Given the extremely low starting rates, we consider these results very promising.

Now that we have this result, an open question remains whether women actually continue using family planning consistently (the next link in the ToC). In the initial study, we see that 87% of women in Lafiya areas reported using their contraceptive method consistently. We see this as a sign that the characteristics of DMPA-SC align well with the needs of the target population. To follow up, we now plan to test these results further through longer-term evaluation and have planned a follow-up study for Q4 2025.

Although it was not a central outcome metric of the study, we also found that in our intervention area, the pregnancy rate at the endline was 6%, while in control areas it was 30%. We see this as a plausible indication that our model is effective at reducing the number of unintended pregnancies.

Our future monitoring and evaluation plans are dedicated to systematically moving toward longer-term health and autonomy results, with the next stage of evaluation examining the impact of our intervention on short-term births and averted unintended pregnancies.

Limitations and open questions

We’re proud of Lafiya’s progress, but we also recognise the limits of what we know. Below are some of the key uncertainties and areas we’re actively investigating. We share these in the spirit of transparency and as an invitation for collaboration and learning.

- We are still studying contraceptive continuation rates over a longer time horizon, and will conduct a follow-up of our field study in Q4.

- We are exploring whether users with increased income and familiarity with family planning may be open to paying for future services; users’ ability to pay is currently an open question.

- Seeing our approach succeed at scale relies on increasing state government investment. While early signs are promising and we have Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) in place, we recognise that political and budgetary priorities can shift, and public procurement commitments may take time to fully materialise.

The launch of our program in Kano and the training of new Lafiya Sisters, November 2024

Scaling plans and strategy for sustainability

We are now focused on:

- Collaborating with the government to sustainably increase access to contraceptive commodities.

- Our first cost-sharing agreement is about to be signed with one state, and we are working on expanding it to two other Nigerian states.

- We are integrating our digital health system of stock management with the governmental systems for increased monitoring.

- We are co-developing a new training curriculum with local government stakeholders to counsel and administer multiple contraceptive methods to ensure that our users can freely choose their preferred method (Lafiya will procure DMPA-SC, whereas the government will procure alternative methods under the co-financing MoU).

- Scaling our innovative last-mile direct delivery model.

- By the end of 2026, we want to scale to 640 Lafiya Sisters (from the current 280) and distribute an additional 1.4 million doses.

- We aim to expand to one additional state in Nigeria, and are considering an additional pilot in a second country to further test our model and its replicability.

- Rigorous impact evaluation

- We are planning a follow-up to our Sokoto field study in Q4 of 2025 to assess the longer-term (16-month) impact of our work.

- We’re planning a process evaluation study to assess the counterfactual impact of several model elements, to see where we can improve further. Specifically, we’ll be studying Lafiya Sisters' decision-making processes, effective distribution pathways, quality of counselling, and post-user experience.

We work closely with partners within the family planning and primary care ecosystem to coordinate our work and leverage respective expertise to advance those objectives.

Funding needs

We are seeking to close a $1.62 million funding gap on our $2.6M 2026 budget [note that we will edit this section regularly as new commitments come in, to give you an up-to-date figure]. We are very intentional about building sufficient runway: continuity of services is essential for our programme. Any interruption of family planning services can lead to immediate risk of unintended pregnancy, reversing months or even years of progress. We’ve also worked hard to build trust with users who rely on consistent access: service gaps would jeopardise this trust and undermine future uptake of services.

Funding would support:

- Expansion to 2 additional states in Nigeria

- Training and supervision for 180 more Lafiya Sisters

- Operational capacity to build out our supply chain strengthening work

- Advocacy to conclude on multiple state governments' co-financing of the commodity procurement

- Our field impact study tracking core impact metrics over the medium-term (16-month and 24-month follow-up to our earlier 8-month study)

We believe Lafiya represents a credible, evidence-backed bet for funders interested in high-upside opportunities within global health, aligned with the evolving thinking of organisations like GiveWell.

Want to talk further?

We welcome you to reach out if you are interested in speaking with us about helping us close our funding gap, partnering to increase our impact, or conducting research on our work.

Please email us at klau.chmielowska@lafiyanigeria.org and celine.kamsteeg@lafiyanigeria.org to continue the conversation.

Our leadership team at EAG London in June 2025 - missing Miranda, our new Director of Advocacy