It was a cold and cloudy San Francisco Sunday. My wife and I were having lunch with friends at a Korean cafe.

My phone buzzed with a text. It said my mom was in the hospital.

I called to find out more. She had a fever, some pain, and had fainted. The situation was serious, but stable.

Monday was a normal day. No news was good news, right?

Tuesday she had seizures.

Wednesday she was in the ICU. I caught the first flight to Tampa.

Thursday she rested comfortably.

Friday she was diagnosed with bacterial meningitis, a rare condition that affects about 3,000 people in the US annually. The doctors had known it was a possibility, so she was already receiving treatment.

We stayed by her side through the weekend. My dad spent every night with her. We made plans for all the fun things we would when she was feeling better.

Monday the doctors did more tests.

Tuesday they told us the results.

My mom wasn't going to wake up. The disease had done too much damage to her brain.

We cried. We said our goodbyes. We kept her company.

A little over a week later, she passed away in peace.

My mom's name was Judy. Not Judith; just Judy.

She grew up in a small town in Illinois. The kind of place people come from but never go to.

She left as soon as she could. She enrolled in the nearby community college, where she met my dad, a recent transplant from Baltimore. He got her attention with his motorcycle. She won him over with a plate of cookies.

They got their degrees, then got married. They honeymooned at Disney World. My mom loved it so much she decided they were going to move there.

That took a few years. First they earned their bachelor's and master's of fine arts. Then they spent time teaching in Ohio. They saved their money, and before long they had enough. They made the move to Florida.

Within the year my mom was pregnant, and in a sign of her connection to Disney, I was due the day of EPCOT's grand opening. My dad wanted us to go so I could be born at Disney. My mom reasonably refused. I must have been disappointed, because I waited three more weeks to join them.

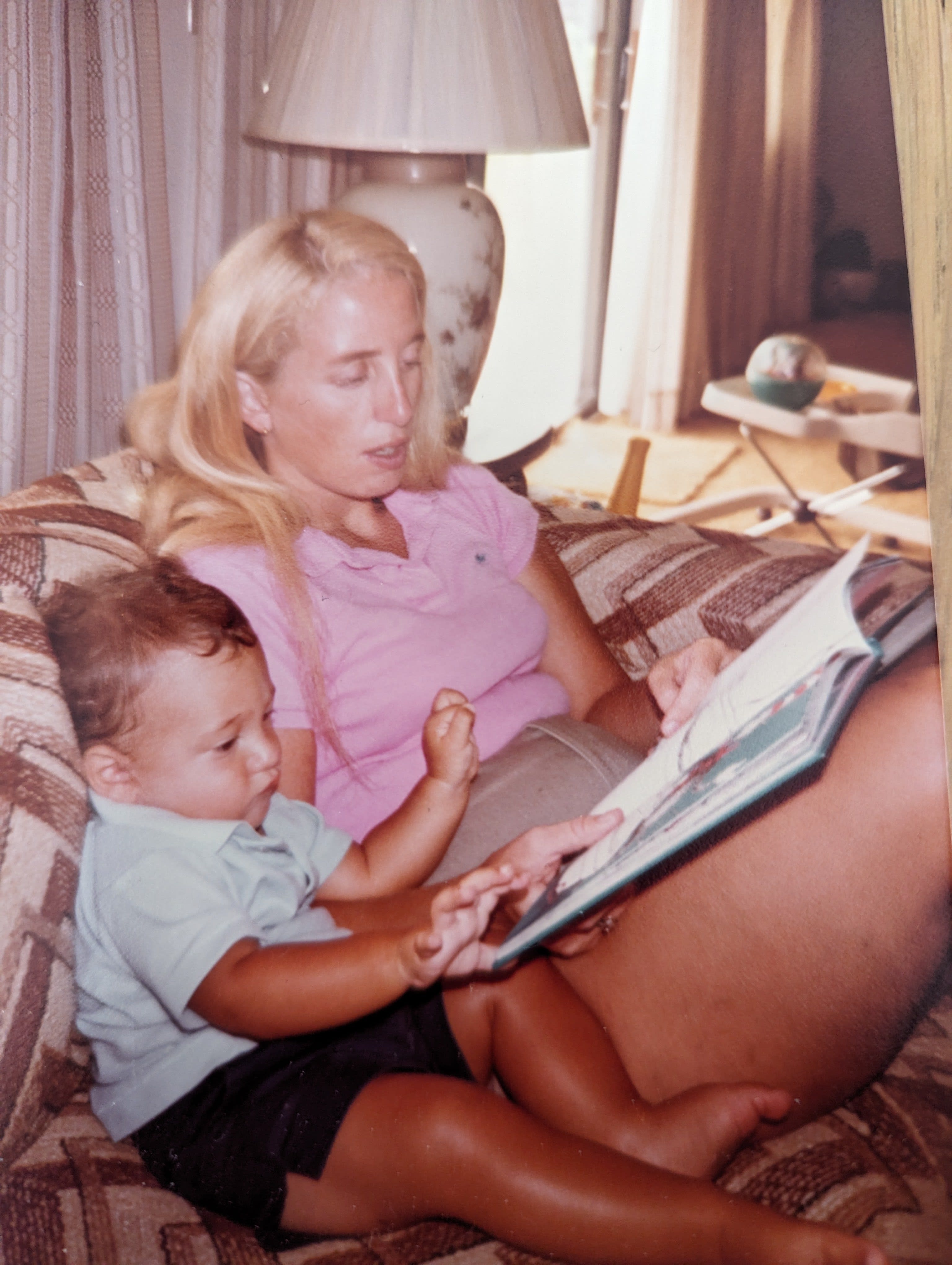

My three sisters soon followed, and my mom took a decade off from teaching to stay home with us. We spent many fun days playing in the yard, swimming in the pool, and tending the garden. When the afternoon sun rose high and threatened to melt us, we'd hide inside to play games, watch TV, and make art.

My mom made a lot of art. She threw pots. She weaved fibers. She painted in oils and drew with colored pencils. A few times a year she'd show her art, along with my dad's, at weekend art festivals. They'd sell a few pieces, but never a lot. They always kept the best stuff on our walls at home.

Most other weekends we were at Disney. On a typical Saturday we'd wake up early, drive through the sunrise to get there before opening, then race to do as many rides as we could before the lines got long. We'd spend the whole day playing, as my mom liked to say, until we were too tired to have fun anymore.

We all had our favorite rides. One of my sisters loved Big Thunder Mountain. Another always wanted to ride the Carousel. I liked Mr. Toad's Wild Ride, and my dad was a fan of anything he could take a nap on.

My mom also had a favorite ride: Peter Pan's Flight.

She never said this to me, but I think she loved that ride because she saw herself in Wendy. Like Wendy, she had to grow up, but that didn't mean she had to stop having fun. With help from my dad—her Peter—and us kids—her Lost Boys—she had many great adventures for many happy years.

This past year was an especially happy one. She and my dad celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. She got to meet her second grandchild. And everyone came home to help her celebrate her favorite time of year—Christmas.

My mom loved almost everything about Christmas. Decorating the tree. Baking cookies. Finding the perfect present to give someone. But what she loved most of all was spending time with family. Having everyone together, all in one place, sharing the little moments of our lives.

Now, we have to go on living our little moments without her.

I've had a lot of feelings about my mom's death.

I've felt sad. I've felt lost. I've felt frustrated and depressed and like wallowing in despair.

I've also been angry.

Angry that she didn't go to the doctor at the first sign of infection.

Angry that doctors had spent years teaching her to delay treatment by dismissing her concerns.

But most of all angry that the world couldn't keep her alive for just a few years more.

Family history suggests she could have easily lived another 5 or 10 or 20 years. And if she had managed to live that long, then she might have lived a lot longer.

In the next two decades we're likely to reach longevity escape velocity: the point at which medicine can increase our healthy lifespans faster than we age. That might sound like science fiction to you, but we're surprisingly close. And with rapid advances in AI, we're accelerating the research necessary to make it a reality.

So while I'm sad my mom didn't live longer, I'm devastated that she didn't live long enough.

And at the same time I'm terrified, because the very AI progress that could have saved her may ultimately be the end of us all.

I've spent 25 years thinking about the potential dangers of AI. Not everyone agrees, but I believe the creation of artificial superintelligence will pose an existential threat to all living beings. I also believe we can avoid this fate, but only if we develop the theories and techniques necessary to steer AI towards supporting life's flourishing.

Before my mom's death, it was easy for me to say we should go slow. That we should take the time to do additional safety research.

Now I know first hand the terrible price of taking even one day more.

The accounting is grim. If we go faster, we might save more lives, but risk the extinction of all life on Earth. If we go slower, we sacrifice millions, but protect the future lives of trillions yet to be born.

Most days I don't think about this tradeoff. I just do what I can that may lead to safely creating AI.

Unfortunately, it's not a lot.

Others are able to do more. I applaud their efforts. I support their work. And I worry that, despite doing our best, we'll still fail.

Yet, I have hope. Maybe I shouldn't, but I do. It's a trait I inherited from my mother. She was a fundamentally hopeful person. I am, too.

I don't know how we'll do it, but I have hope we'll find our way through.

And if we do, it won't bring back my mom. But she will be among the last of the moms we had to lose. I hope that will be her legacy, and the legacy of every person we lost too soon.

Cross-posted from my blog.