TL;DR

In this post, I will share the work I have done on the topic of civilisational shelters (1), (2), over the last year as an architecture master's student. I will share my dissertation on improving the social dynamics of confined spaces, including a practical design guide that can be used to design new or evaluate and improve existing confined spaces. I will also share the Shelters Precedents Report Draft I worked on last spring.

Key links from this post include:

- My dissertation in pdf or flipbook formats

- Link to the Wellbeing Worksheet, an interactive design guide proposed in my dissertation

- Video summarising the research and findings (especially useful if you want to learn about my design proposal and the design guide)

- Link to the Shelters Precedents Report Draft

Outline

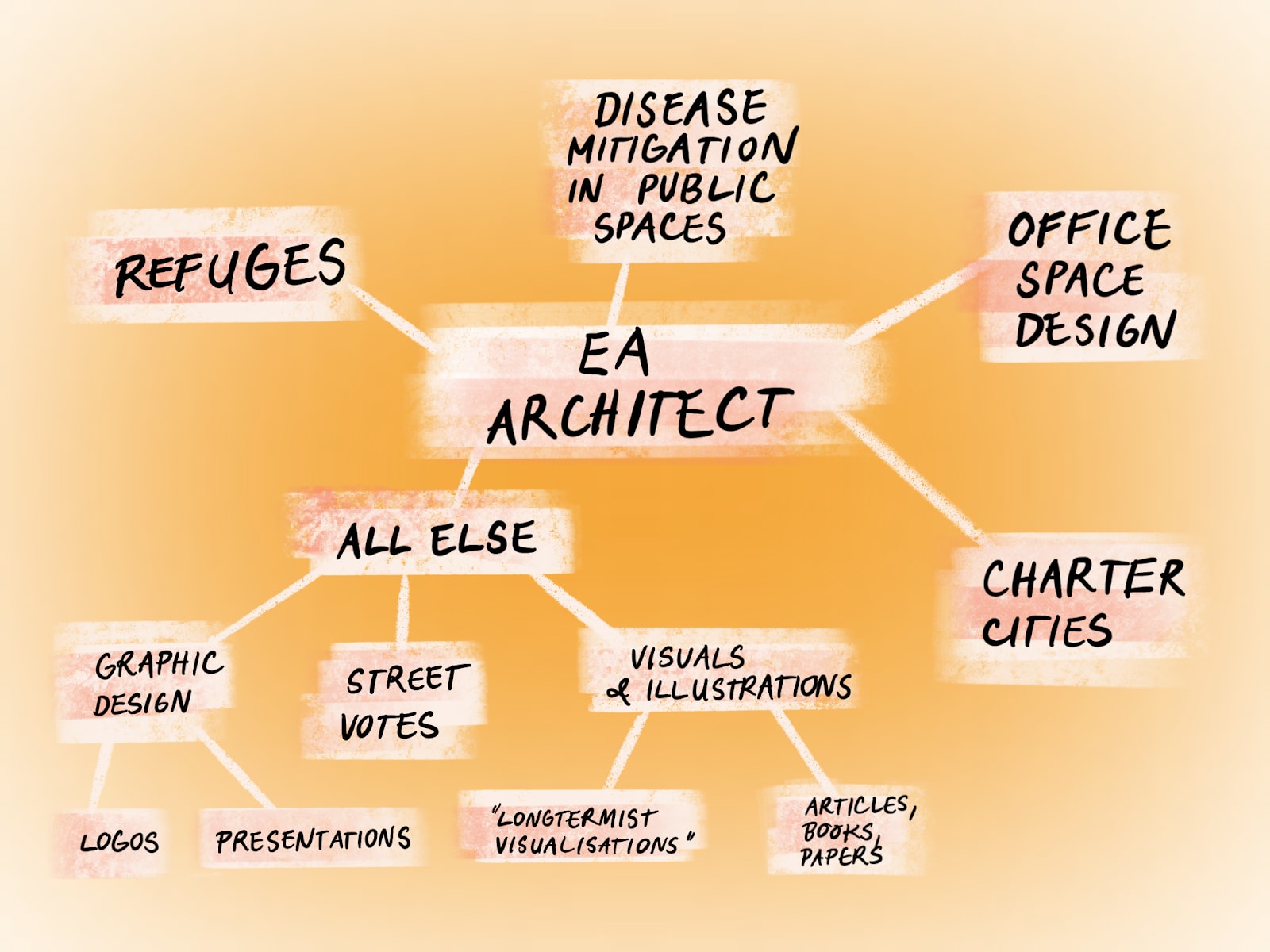

Since last spring, I have explored ways to get involved in EA with my skills as an architect. So far, I wrote this and this article about my ideas and journey of becoming the ‘EA Architect’, and have also started to help anyone with architectural or planning background get involved through the EA Architects and Planners group. One of the key areas I got involved in was civilisational shelters. This summer, I am going to Zambia to intern with the Charter Cities Institute.

This post has two parts:

- Part 1: My architectural research-led dissertation on ‘Improving the Social Dynamics of Confined Spaces Located in Extreme Environments’;

- Part 2: Sharing the Shelters Precedents Report Draft I developed last spring and so far only shared internally.

Part 1: Improving the Social Dynamics of Confined Spaces Located in Extreme Environments

After co-organising the SHELTER Weekend last summer (see this post by Janne for a summary of what has been discussed), as well as studying various precedents and talking to many experts, I concluded that the best way I can contribute to the shelters work is by understanding what influences the social dynamics of very confined spaces. Hence, I chose this as my master’s thesis at Oxford Brookes.

Why I did it

Global catastrophes, such as nuclear wars, pandemics, asteroid collisions or biological risks, threaten the very existence of mankind (Beckstead, 2015). These challenges have caused people to consider distant locations such as polar regions, deep sea, outer space, and even underground facilities as potential locations to seek safety during such crises (Beckstead, 2015; Jebari, 2015). However, living in confined spaces for prolonged periods brings prominent social challenges that might prevent their long-term success (Jebari, 2015). To ensure the successful habitation of confined spaces, special attention needs to be given to their design, allowing humans to survive and thrive long-term.

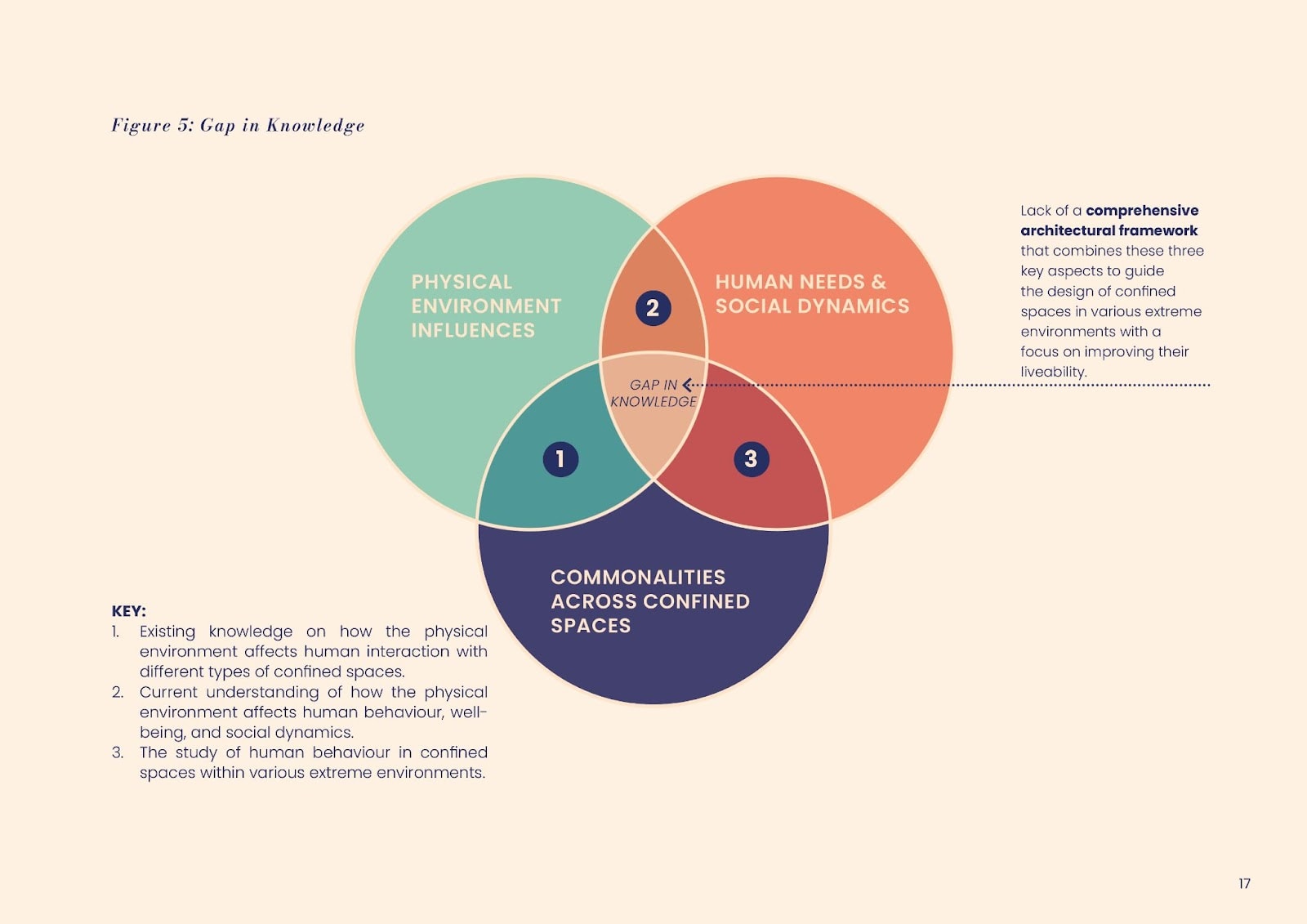

While there is existing research on the design of specific confined spaces, like the design of research stations in polar regions (Bannova, 2014; Palinkas, 2003), space stations (Basner, Dinges, et al., 2014; Harrison et al., 1985), prisons (Karthaus et al., 2019; Lily Bernheimer, Rachel O’Brien, Richard Barnes, 2017), biospheres testing space habitation (Nelson et al., 1994; Zabel et al., 1999) or nuclear bunkers (Graff, 2017; NPR, 2011), there seems to be a lack of a comprehensive architectural framework that can be utilised by designers of confined spaces in extreme environments to help improve their liveability. This is despite the fact there has been much research on the impacts of the physical environment (Klitzman and Stellman, 1989), including staying indoors (Rashid and Zimring, 2008), thermal comfort (Levin, 1995), the impact of light (Basner, Babisch, et al., 2014) and noise (Levin, 1995) on stress levels, psychological well-being and health.

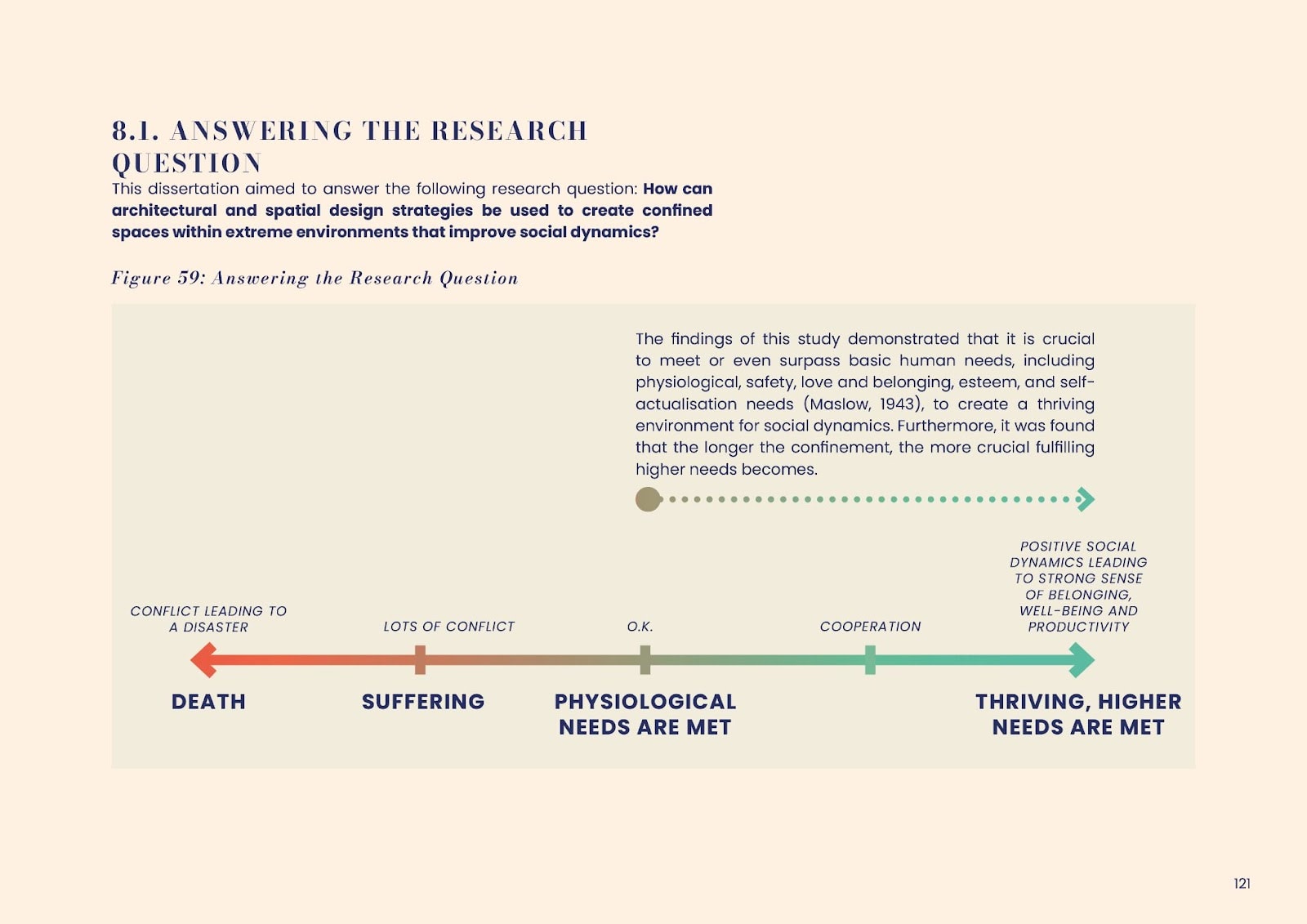

Therefore, my dissertation aimed to investigate the role of architectural and spatial design strategies in creating confined spaces within extreme environments that improve social dynamics. The research question I asked was: How can architectural and spatial design strategies be used to create confined spaces within extreme environments that improve social dynamics?

What I did

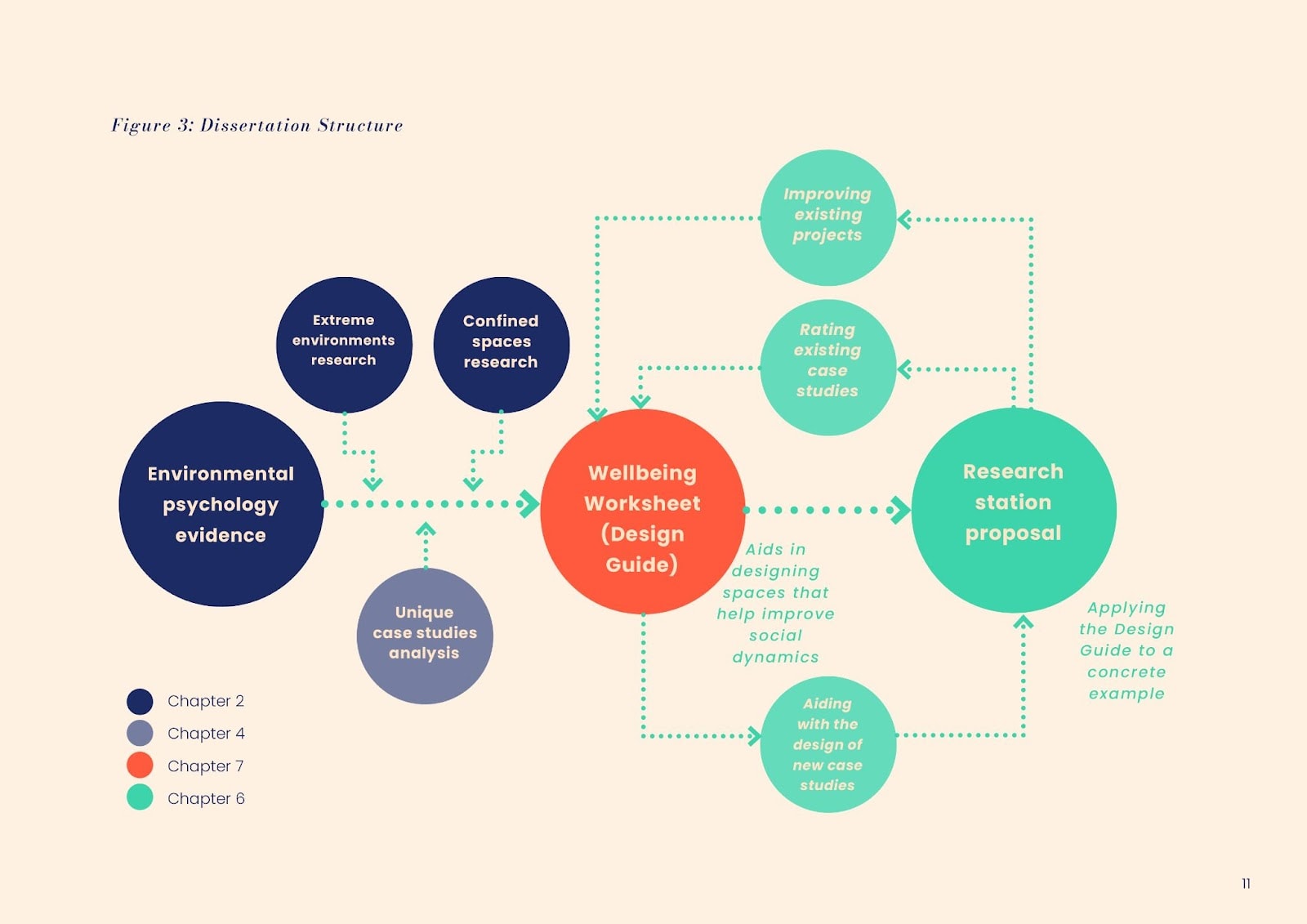

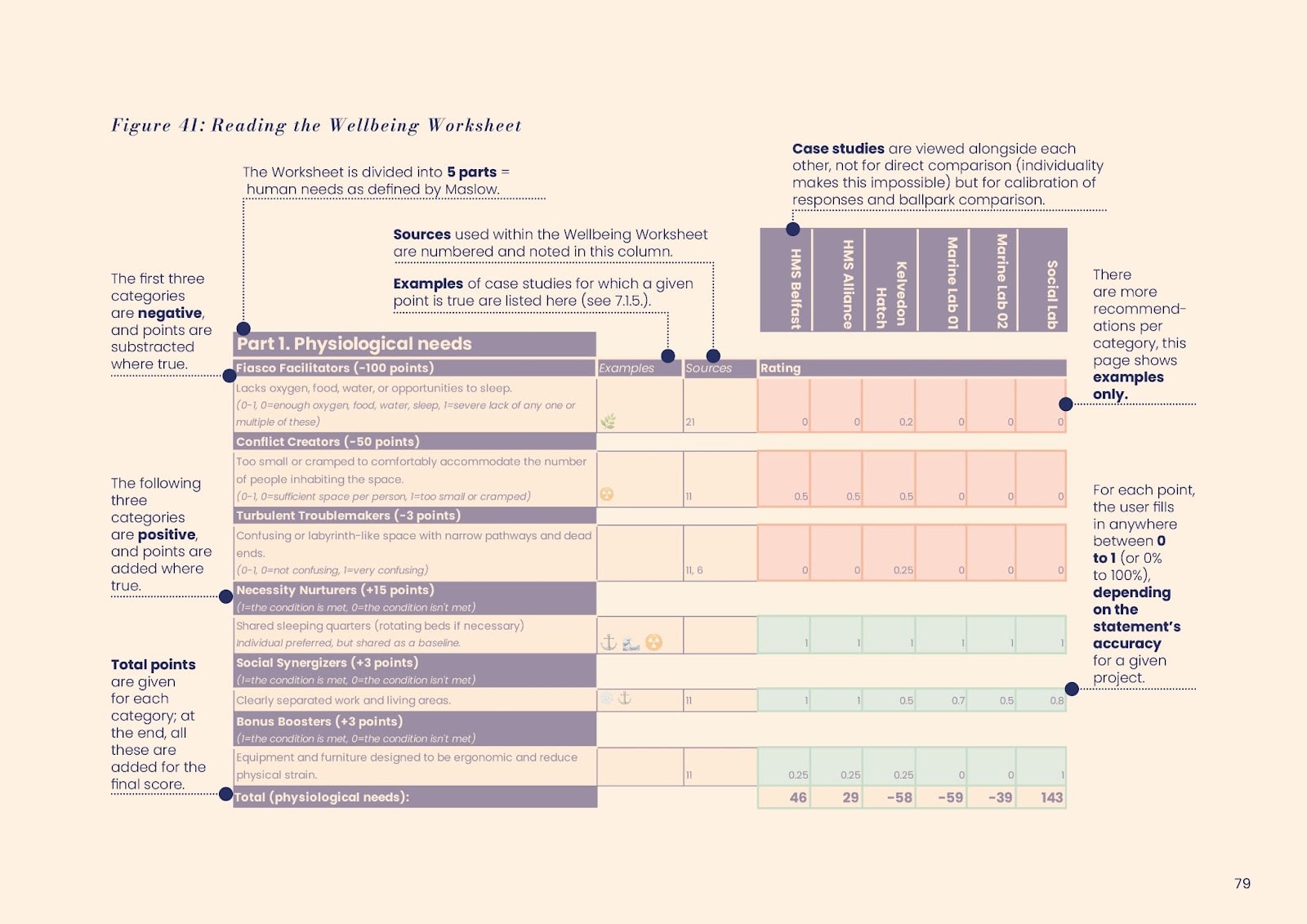

My dissertation investigates how architectural and spatial design strategies can be used to enhance social dynamics in confined spaces within extreme environments. I developed a practical design guide (which I called the ‘Wellbeing Worksheet’ and you can find here), drawing from literature on environmental psychology, confined environment design, space psychology, and sociology. The design guide addresses individuals’ physical and psychological needs, and I employed relevant case studies to determine the transferability of design principles across domains.

The Wellbeing Worksheet can be used to evaluate existing confined spaces, enhance existing spaces, and create new ones. Applying the design guide, I proposed a research station simulating life in confined spaces in extreme environments (plan view of the final proposal. The proposal is covered in depth in Chapter 6. I also designed two more confined iterations shown in Chapter 5). The proposed station aims to examine the social dynamics and psychological aspects of living in confinement while providing training for crewmembers.

Methodologies and methods

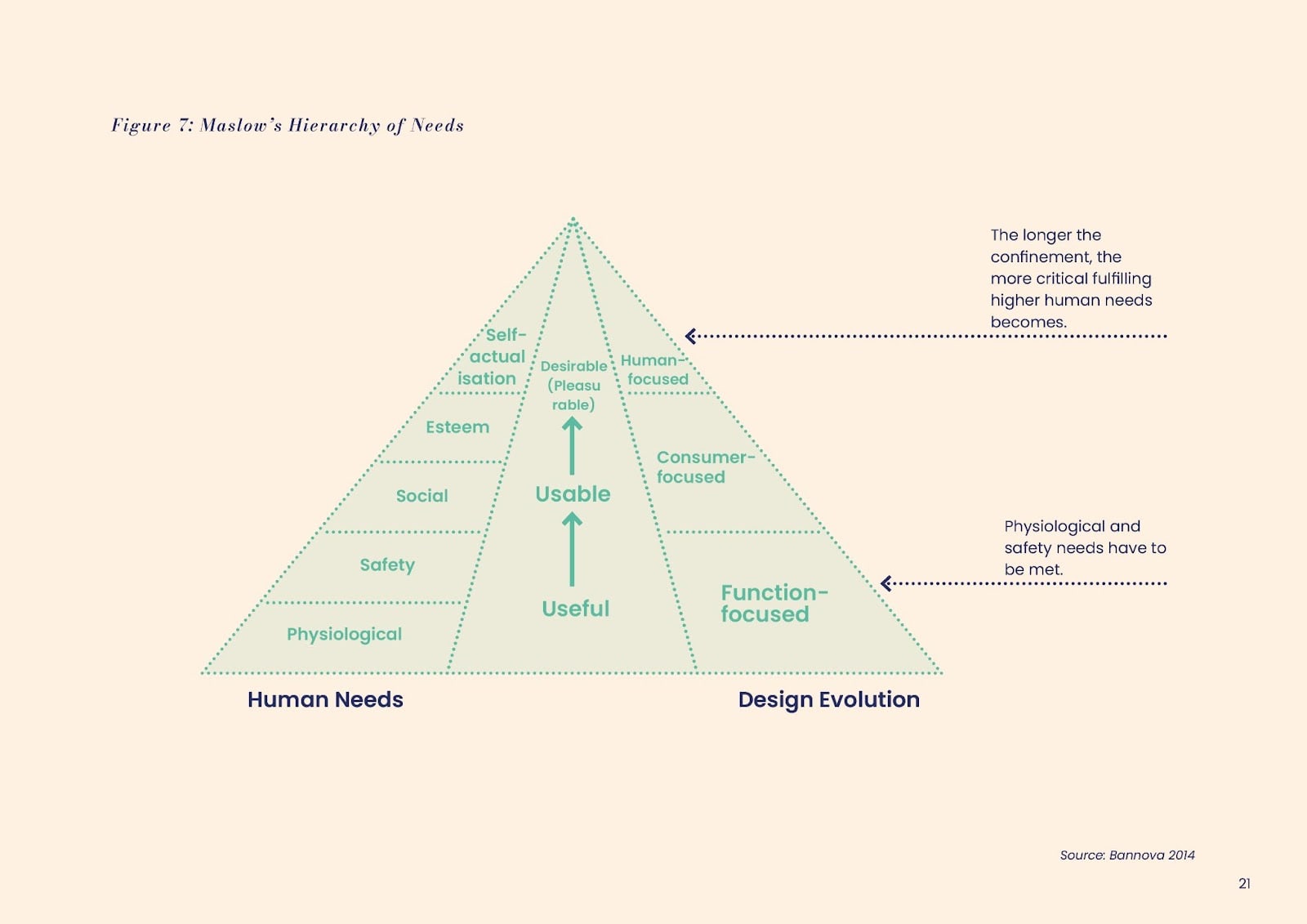

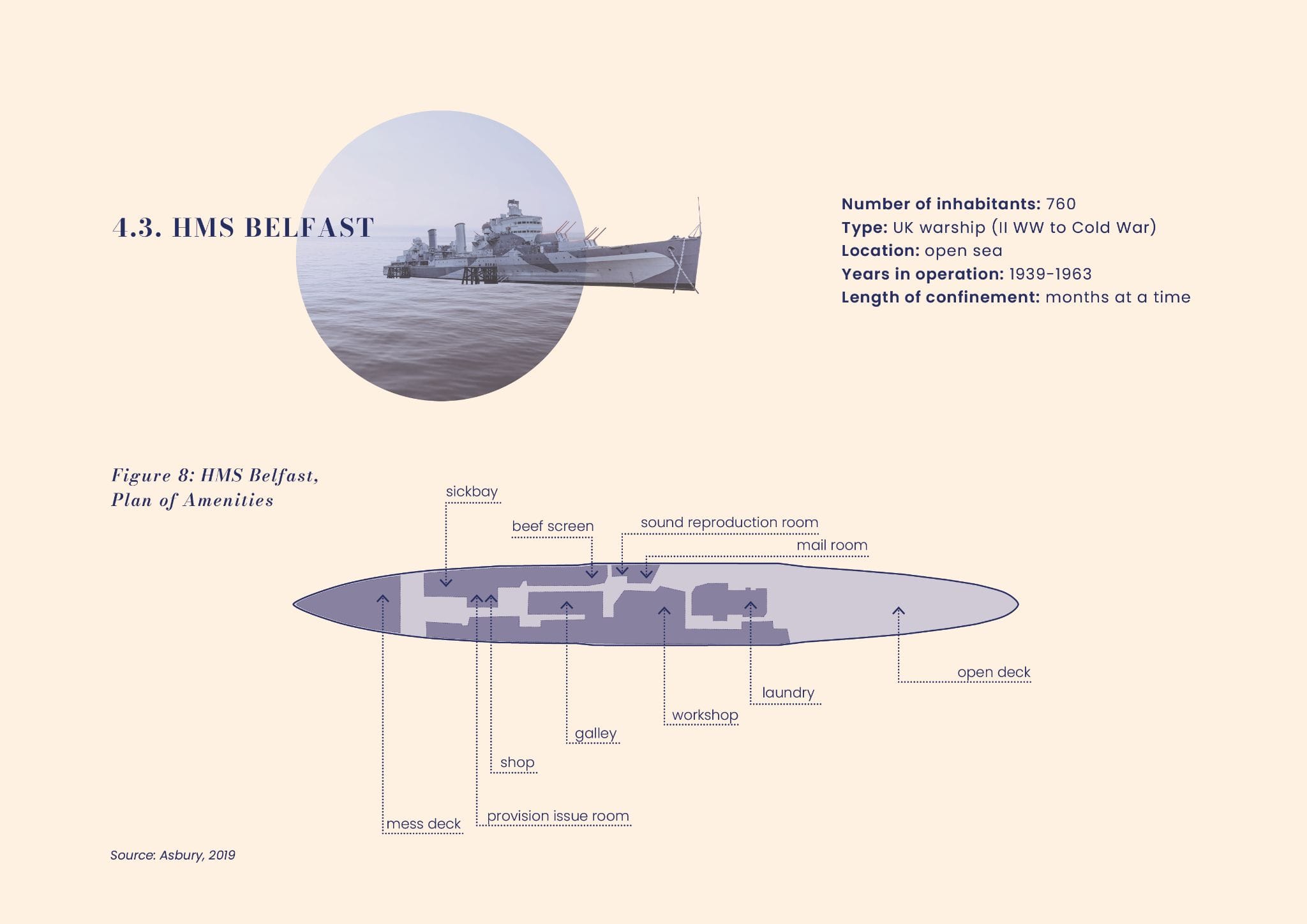

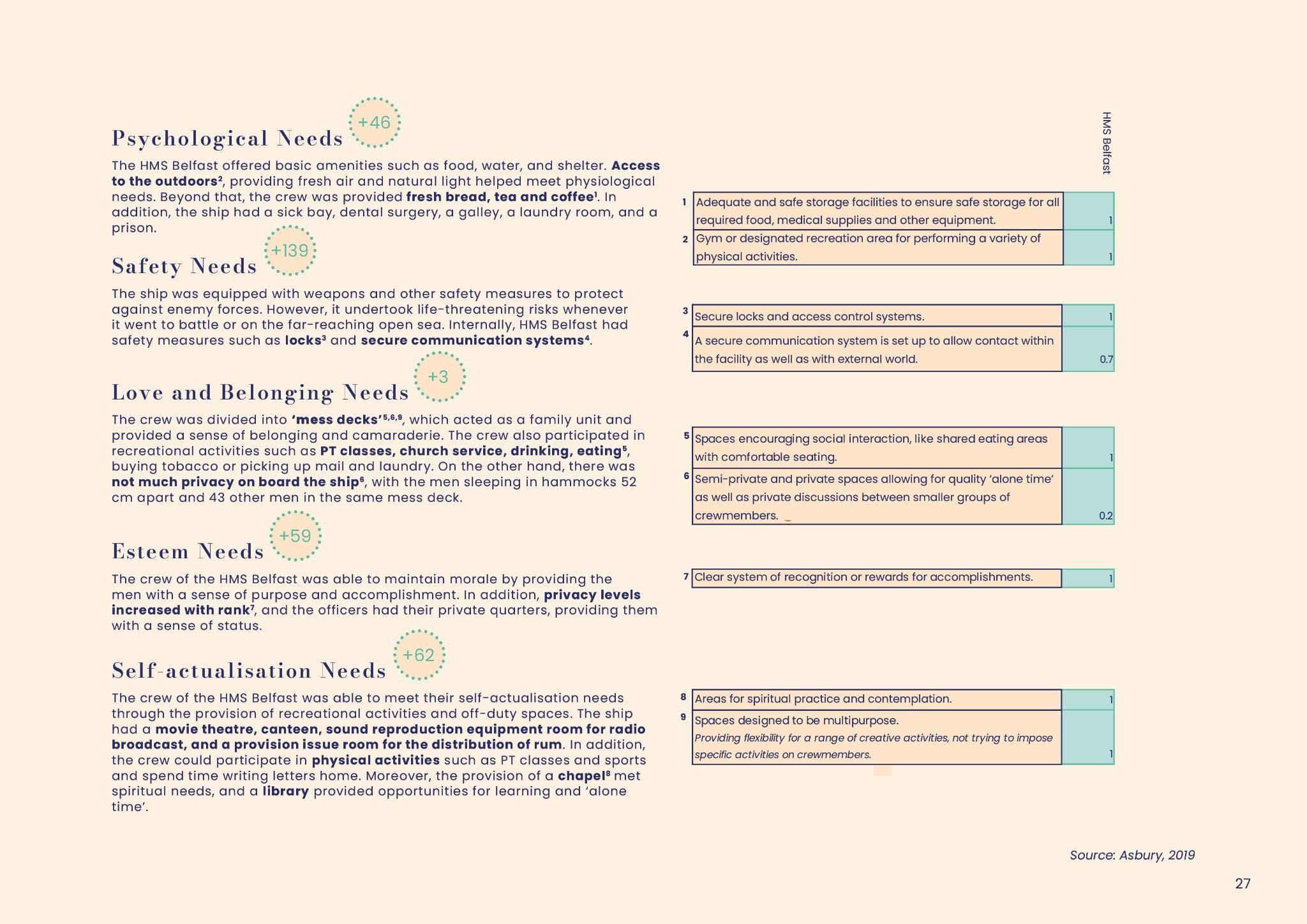

I adopted a mainly qualitative research approach, using Maslow’s hierarchy to examine confined spaces in extreme environments. The primary research methodology is the case study approach. Three cases - a nuclear bunker (Kelvedon Hatch, UK), a submarine (HMS Alliance, UK), and a warship (HMS Belfast, UK) - have been selected for relevance to the research question and firsthand site visit experience. Cases are evaluated using archival data and direct observation, with desktop analysis of other precedents supplementing findings.

Employed research methods include:

- Archival Data Analysis: Using various data sources to gain insight into occupants’ experiences.

- Direct Observation: Observing case studies firsthand to identify design strategies.

- Application of the Wellbeing Worksheet: Applying the Wellbeing Worksheet (Chapter 7) as a systematic method for assessing and designing confined spaces.

- ‘Day in the Life’ Method: Imagining moments within case studies to inform design development.

Conclusions and key findings

I explored the role of architectural and spatial design strategies in creating confined spaces within extreme environments that improve social dynamics. I developed a framework and design guide and came to appreciate the significance of meeting and surpassing basic human needs, such as physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation needs (Maslow, 1943). My case study analysis revealed key strategies for enhancing social dynamics in confined environments, including providing larger spaces, ensuring lower densities, incorporating variety and flexibility, and fostering a shared sense of purpose (Harrison et al., 2012).

The design guide was tested by designing a research station simulating life in extreme conditions, which could further test social dynamics and psychological aspects of living in confinement and provide training for crewmembers.

Key findings related to how architectural strategies can be employed to meet or surpass individual human needs and consequently improve social dynamics include:

- Meeting physiological needs by providing oxygen, food, water, and sleep facilities. To surpass these needs, offer daylight or its imitation, ventilation and filtration systems, heating and cooling, medical care, and nourishing food. Surprisingly, personal comfort alone does not significantly impact social dynamics.

- Addressing safety needs by implementing monitoring systems, secure locks and access control, fire and smoke detection, emergency lighting and alarms, and fire suppression systems. Also, consider structural integrity and provide secure alternatives in case of key system failures.

- Fulfilling love and belonging needs by respecting crew privacy, avoiding crowding, and designing areas promoting social interaction and collaboration, such as shared eating areas. Group rituals, consistent rules, expectation management, and activities like cooking and eating in shared spaces foster connections.

- Meeting esteem needs by offering opportunities for individual achievement, recognition, and rewards. A shared sense of purpose is vital for satisfying esteem needs. Additionally, providing diverse spaces and activities helps prevent boredom, while adaptability and flexibility create universal spaces catering to personal preferences.

- Addressing self-actualisation needs by granting access to resources and activities that encourage creativity and spiritual contemplation. Consider different personalities, allowing for highly social as well as private and quiet activities. This includes meditation and spiritual contemplation spaces, libraries, virtual reality, workshops, and comfortable common areas for discussions.

I have tried to fill a knowledge gap by providing a design guide for architects and designers to evaluate and enhance existing spaces or inform new confined environment designs. Moreover, I have demonstrated the relevance and application of these design strategies in real-world settings, contributing to the well-being and success of those living and working in extreme conditions (Harrison et al., 2012).

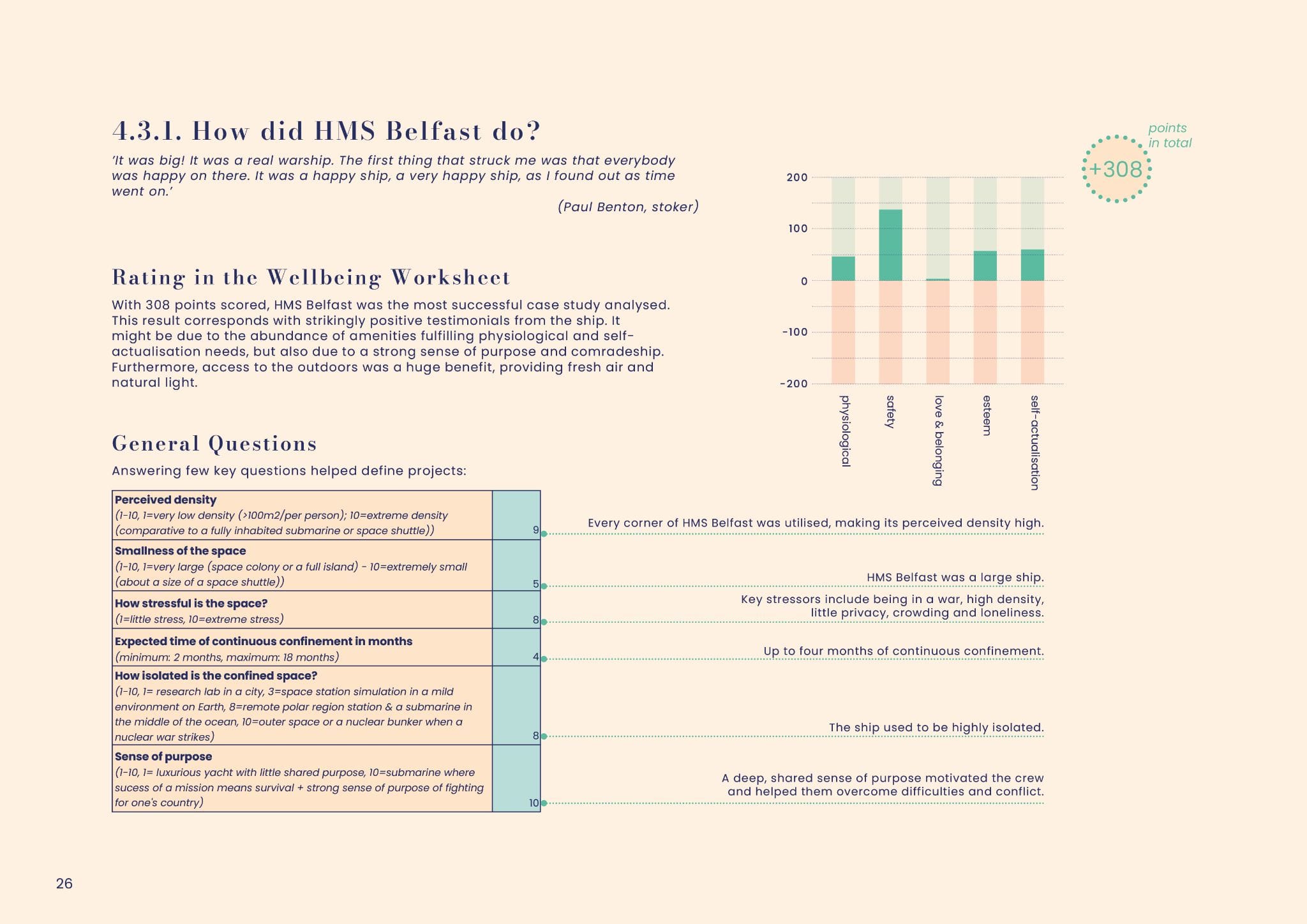

HMS Belfast: Examples of Findings from Successful Case Studies

Some surprising learnings came from analysing confined spaces with rich social structures and well-functioning social dynamics, such as the UK warship HMS Belfast.

Launched in 1938 and decommissioned in 1961, HMS Belfast offered various spaces to meet inhabitants’ needs, including a medical centre, canteen, laundry, movie theatre, and chapel (Asbury, 2019). The ship’s size enabled movement, exercise, and outdoor time, contributing to the crew’s well-being. Personal accounts highlight strong relationships formed among crew members, with competition between groups fostering bonds. A shared purpose, clear social hierarchy, and the military chain of command facilitated conflict resolution.

With 308 points scored, HMS Belfast was the most successful case study analysed. This result corresponds with strikingly positive testimonials from the ship. It might be due to the abundance of amenities fulfilling physiological and self-actualisation needs, but also due to a strong sense of purpose and comradeship. Furthermore, access to the outdoors was a huge benefit, providing fresh air and natural light.

Limitations and Future Research

This dissertation has limitations that require further research:

- Theoretical context: The study relies on a theoretical framework and case studies, but empirical research could strengthen the findings by validating the effectiveness of the design guide in improving social dynamics in confined spaces.

- Lack of empirical testing: The proposed design guide has not been tested in real-life situations, limiting its validation. Constructing and testing spaces designed using the Wellbeing Worksheet can explore the impact of architectural strategies on social dynamics.

- Limited scope of case studies: Additional case studies from different extreme environments would enhance understanding of the design strategies' applicability.

- Duration of confinement: The relationship between confinement duration and the importance of self-actualisation needs further exploration, especially in case studies involving extended habitation.

- Cost-effectiveness analysis: Future research should consider cost in scoring mechanisms.

If you want to learn more

- Flip through my dissertation to learn more.

- Or, see the pdf on Google Drive to make comments directly in the document. Any comments are welcomed.

- Or watch a video where I guide you through it.

If you are interested in learning more, using my design guide or applying my research, feel free to reach out to me at tereza.flidrova13@gmail.com, I would be excited to hear from you.

Part 2: Shelters Precedents Report Draft

This report offers a summary of precedents that have the potential to inform the design and processes of shelters. It is a tool that allows comparing different aspects of designs, like layouts, sizes, construction methods and costs, and, where relevant, draws parallels to shelters.

Where relevant, this report also incorporates findings from key writings on shelters to date.

It's been noted that we might need a diversity of different typologies of shelters. This report provides a sample of the existing variety and suggests a direction for future research.

The precedents this report focuses on are:

- Continuity of Government Bunkers

- Government Bunkers for Citizens

- Private Shelters

- Research Stations in Remote Locations

- Research Experiments (like Biosphere 2)

- Laboratories (BSL-4)

- Island Refuges

- Peoples Living in Seclusion

- Submarines

- Space Exploration

- Seed Banks

For each case study, there are the following sections that allow cross-comparison:

- Quick facts

- Why is it relevant? ⚙️

- Sources ℹ️

- Videos 🎥

- Type

- Location📍

- Size 📏

- Capacity 👭

- Tags

- Year built ⏳

- Owner

- Supplier 👷

- Costs 💰

- Layout

- What threats does it protect from? 💣

- Safety and design features ⚠️`

- Fun facts 🧬

- Main design limitations 🚫

- People to reach out to

The report also includes Editor’s picks to direct the reader to intriguing or relevant findings. I enabled anyone to comment on the document and created this form to allow anyone to submit information about additional precedents.

Thanks a lot for reading this post, and if anyone is interested in this topic, feel free to reach out, I would be happy to chat.

Bibliography

Asbury J (2019) HMS Belfast. IWM Publishing.

Bannova O (2014) Extreme Environments: Design and Human Factors Considerations. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/074fe7a38f93be1a6ce496da9976afc0/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

Basner M, Babisch W, Davis A, et al. (2014) Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. The Lancet 383(9925): 1325–1332.

Basner M, Dinges DF, Mollicone DJ, et al. (2014) Psychological and behavioral changes during confinement in a 520-day simulated interplanetary mission to mars. PloS one 9(3): e93298.

Beckstead N (2015) How much could refuges help us recover from a global catastrophe? Futures 72: 36–44.

Graff GM (2017) Raven Rock: The Story of the U.S. Government’s Secret Plan to Save Itself--While the Rest of Us Die. Simon and Schuster.

Harrison A, Sommer R, Struthers NJ, et al. (1985) Implications of privacy needs and interpersonal distancing mechanisms for space station design. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/8f53f718f073c0553950571708550889acf558e5 (accessed 27 October 2022).

Jebari K (2015) Existential risks: exploring a robust risk reduction strategy. Science and engineering ethics 21(3): 541–554.

Karthaus R, Block L and Hu A (2019) Redesigning prison: the architecture and ethics of rehabilitation. Journal of Architecture 24(2). Informa UK Limited: 193–222.

Klitzman S and Stellman JM (1989) The impact of the physical environment on the psychological well-being of office workers. Social science & medicine 29(6): 733–742.

Levin H (1995) Physical factors in the indoor environment. Occupational medicine 10(1): 59–94.

Lily Bernheimer, Rachel O’Brien, Richard Barnes (2017) Wellbeing in Prisons: A Design Guide.

Nelson M, Dempster W, Alvarez-Romo N, et al. (1994) Atmospheric dynamics and bioregenerative technologies in a soil-based ecological life support system: initial results from Biosphere 2. Advances in space research: the official journal of the Committee on Space Research 14(11): 417–426.

NPR (2011) The Secret Bunker Congress That Never Used. 26 March. NPR. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2011/03/26/134379296/the-secret-bunker-congress-never-used (accessed 13 June 2022).

Palinkas LA (2003) The psychology of isolated and confined environments. Understanding human behavior in Antarctica. The American psychologist 58(5): 353–363.

Rashid M and Zimring C (2008) A Review of the Empirical Literature on the Relationships Between Indoor Environment and Stress in Health Care and Office Settings: Problems and Prospects of Sharing Evidence. Environment and behavior 40(2). SAGE Publications Inc: 151–190.

Zabel B, Hawes P, Stuart H, et al. (1999) Construction and engineering of a created environment: Overview of the Biosphere 2 closed system. Ecological engineering 13(1): 43–63.

Hi Tereza !

First of all, congratulations on your ambition and perseverance in your project!

In this publication, you touch on many aspects of typically well-being, happy existence and social cooperation. These are not areas in which I am an expert, so let me go a little further and ask you what tangible next steps you plan to take in the field of investment, not just research? Do you see promising prospects for such an investment? Which organizatsions could provide funding (or are already doing so?). Who do you need on the team to work on it? Of course, I ask for a reason :) As you know, I work in a similar industry to you (designing installations in buildings) and, like you, I am looking for a place to use my competences in the EA world. I am excited about your research and would like to consider joining forces on such a project. If you have time and space to expand this discussion, I'm waiting for it on priv :)