TL;DR: I'm trying to get across an emotionally useful framework for thinking about emotionally useful frameworks (optimisms), "the bar of success" and personal responsibility.

Every agent faces a fundamental problem: When to stop thinking and start acting? (exploring/exploiting) Humans have solved this by becoming satisficers. Instead of figuring out the optimal action at every point in time, we merely act in a way that feels "good enough".

From the perspective of our value function, this "satisfaction bar" is meaningless - there is only a list of outcomes that differ in desirability. Nevertheless "being enough" or "meeting expectations" or "doing good, relative to others" seems to form an important psychological anchor that defines other arbitrary lines such as "terrible", "good" and "excellent".

We enter every situation (episode) with a similar "expectation bar" for how pleasant the event will be and how well we will perform. If reality falls below our expectations, we feel bad; if reality outperforms them, we feel good.[1] This expectation bar then determines how the given situation is evaluated and our behavior conforms to this feedback (cf. RL; predictive processing; CBT).

Therefore, emotions are quite firmly tied to our expectation bar. They are the brain's coordination mechanism, in response to novel information or uncertainty. They represent a compressed model of our satisfaction in every dimension and direct our attention to those that seem neglected - and as such, they provide useful information that calibrates our motivation and alertness.

However, the way emotions manifest seems somewhat arbitrary. From the adaptive or decision-making perspective, it is not important whether we experience motivation as "desiring a good thing" or "desiring less of a bad thing": goodness and badness are just two inverse names for a perfectly overlapping spectrum. However, there is a big difference from the experiential perspective.

And this difference is particularly important, when it comes to abstract, big picture concepts like "the loss of the aggregate wellbeing trillions of years into the future": those that matter the most but where there is little adaptive value in imagining them accurately. And so, in response to cognitive dissonance, it is frequently easier to "imagine such problems away", rather than trying to feel their appropriate emotional weight.

However, neither is optimal. I find it useful to imagine yourself as "one neuron of humanity". The brain can lose any individual neuron without collapsing. Yet, the whole system is nothing more than a collection of individual neurons[2]. At the same time, every neuron is good for something else, so it is useful to specialize (to allow other neurons to rely on you) but sometimes defer to other "expert neurons", instead of torturing yourself until you understand every detail of every modern conflict.

This is where the analogy slightly breaks down, because people do often "stay in their lane" by default - and it is one reason why global, systemic problems are neglected. But perhaps, you can identify as a "metacognition" neuron whose job is to correct for these global, systemic problems. Nevertheless, it is not productive to process all global suffering, that is - to take its weight just upon yourself - i.e. spending all your capacity on merely simulating its terribleness. Rather, your responsibility should be to pass on the right signals and hope they catch on. And your ambition should be to be a particularly "inspiring neuron" that can trigger a ripple effect by igniting a whole cortical column.

Perhaps you can see narratives like this don't really alter your "empirical picture" of the world - yet, they matter emotionally, as your concept of identity determines what you count as a "success" or how you feel and prioritize.

Importantly, the count of "success" is partially arbitrary, as your "expectation bar" can differ, depending on the level of description you choose - e.g. what we would expect from the world differs, based on the prior/counterfactual we are considering. When it comes to broad emotional narratives of "who we are" and "how good we're doing", we can tell many truths, which gives us the flexibility to choose to tell ourselves the helpful ones.

My model

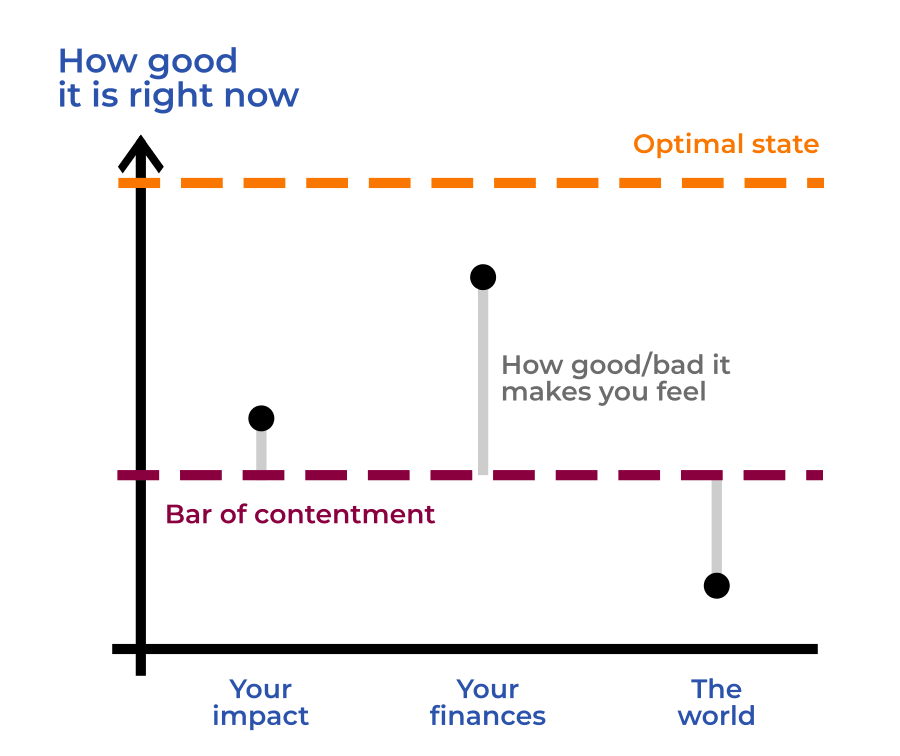

Let's illustrate what I mean. From the experiential perspective, there is the expectation bar - the emotional level of comparison at which your emotions are neutral: everything above it is felt as success, everything below as failure. From now on, I will call it the "bar of contentment" because it seems broader than "expectation", as often situations feel disappointing even though we didn't consciously predict they would be better.

You could also call it the "satisfaction bar" but I use "contentment" to stress that the bar only refers to emotional, not moral/rational zero point. In terms of your "intellectual mindset", it is good to be always dissatisfied, to always strive for the optimum. However, in terms of emotions, I think we should strive for the precise opposite. We should always be "content" - i.e. instead of torturing our own minds when we see suffering, we should approach it with equanimity, and meet every speck of kindness and sanity in this world with gratitude.

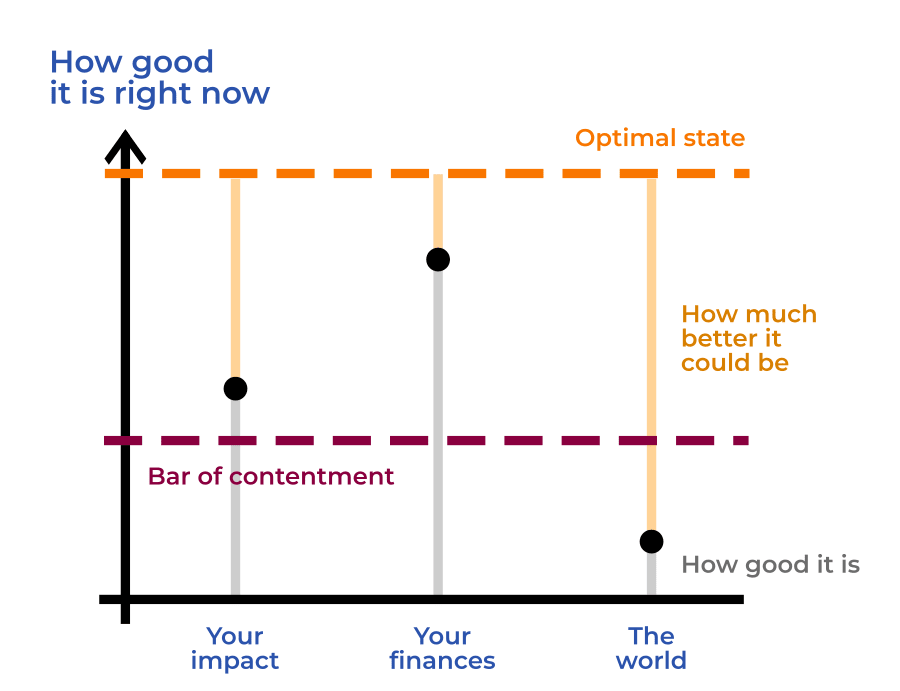

In contrast, from the decision-making perspective, the bar of contentment doesn't really make a difference, i.e. rationally, it makes more sense to view it like this:

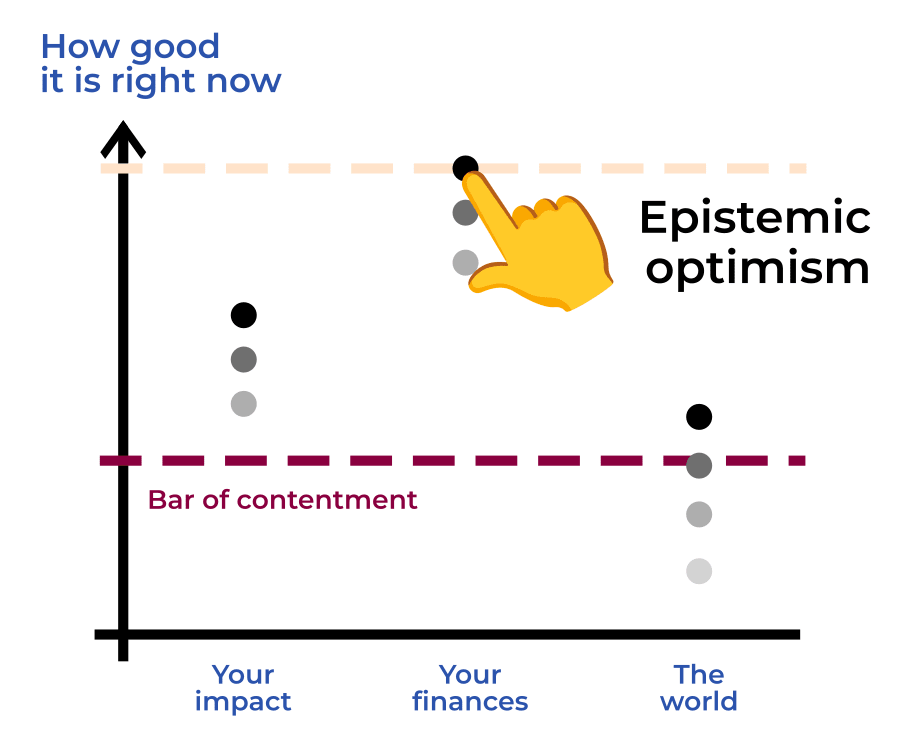

Now, this model offers two strategies for feeling better about the world. The first one is what I call epistemic optimism. In this strategy, people respond to bad things in the world by convincing themselves these bad things don't exist or are not actually bad. In other words, they redraw their world model - shift their "data points" - in order to make it seem, as if it's actually quite close to the optimum.

And so, when people hear about extreme poverty, they convince themselves "one person can't change anything", when they hear about animal suffering, they convince themselves animals aren't conscious and when they hear about climate change or AI x-risk, they convince themselves they can't be real.

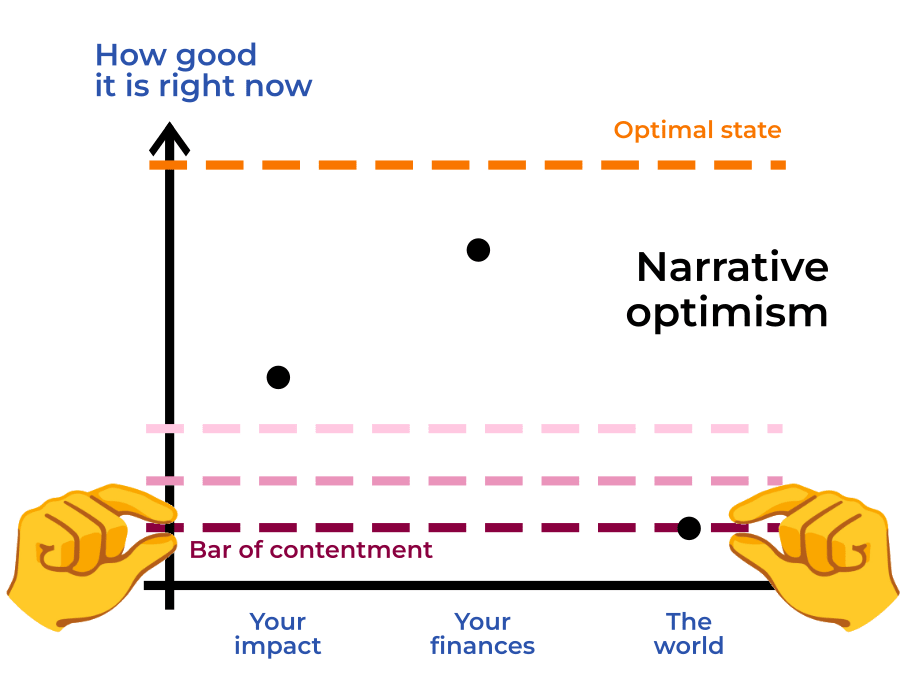

A better idea is something I call narrative optimism. This strategy responds to bad things by putting them in a perspective that takes away their negative emotional weight, ideally without sacrificing an accurate picture of reality.

Of course, the simplest, science-stamped hack for lowering your bar of contentment is gratitude. For instance, many people in the developed world feel like they are barely holding on when they cannot afford what others can. However, holding in mind how our condition compares to the rest of humanity or the vast majority of people in history, gives us a different picture. Not to mention, how "lucky" we are to be humans, rather than animals or mere cellular life forms. For me, the gratitude for my own life in no way diminishes how much suffering there is - if anything, it makes it "more real". Yet, it makes me feel better than striving for the arbitrary bar of contentment set by status norms.

(I'm not recommending that people should keep their bar of contentment at zero at all times. Sometimes, it seems wise to share a bit of suffering with others, to reconnect with your values and recalibrate your priorities or just to be a human when others need your support. However, most of the time it's not productive to suffer.[3])

Why

I had two motivations for writing this post. Firstly, I think it is very harmful that society doesn't really distinguish between narrative and epistemic optimism - both for our collective happiness and epistemics. People imagine a grand future for themselves and the world and when evidence to the contrary emerges, they suffer because the world failed to meet their expectations. And so, people are constantly shocked by news headlines, predictably updating only in the direction of "the world is bad", as if it's obvious that in all parallel universes, the world is better. In my understanding, this is one big idea behind stoicism.

Once you start noticing it, you will constantly see, just how often people confuse their hopes for their expectations. Yudkowsky recounts a typical example:

Once upon a time, I went to EFNet’s #philosophy chatroom to ask, “Do you believe a nuclear war will occur in the next 20 years? If no, why not?” One person who answered the question said he didn’t expect a nuclear war for 100 years, because “All of the players involved in decisions regarding nuclear war are not interested right now.” “But why extend that out for 100 years?” I asked. “Pure hope,” was his reply.

The second reason is tangential and much more speculative - but it gives me an intuitive reason to trust that, perhaps outside of extreme poverty, mental health interventions might be more effective at increasing happiness than economy-focused ones, as one could infer from the Happier World reports (+ their critique) and some disappointing recent UBI results. Even though the world GDP is 10 times higher than it was in 1960, human happiness is likely not 10 times higher. I think we could see this dilemma using the same metaphor, where we can either make the world happier by trying to "move the data points up" or "move the bar of contentment down". Even though money does actually make most people somewhat happier, changing the algorithm that ties people's happiness to their relative socioeconomic status might be cheaper.

However, this model also offers one explanation for why measuring the effects on happiness seems so hard, as it is hard to distinguish between a "reporting effect" and "experiential effect". To a certain extent, relative rating of your happiness is merely a question of how high you put your arbitrary bar of contentment. But at the same time, studies suggest that the way you feel does actually depend on how you score your life relative to your bar of contentment - as that seems to depend on the prominent thoughts in your mind and the narratives behind them.

- ^

An illustration of how interpretation/narrative can make a big difference: If you feel bodily discomfort during a medical examination, you might not feel any emotion. If you walked on a street and suddenly experienced the identical sensation, you might, e.g. feel a stark confusion and anger.

- ^

This is a lie because I don't have a good metaphor for astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, endothelial cells & pericytes (BBB), ependyma/choroid plexus (CSF), meningeal fibroblasts, resident immune cells, and the extracellular matrix/perineuronal nets (thanks, ChatGPT).

- ^

I disagree with Paul Bloom's framing of this argument in Against Empathy but he provides a lot of evidence for this claim.