Note: this post was crossposted from Elizabeth's blog, Aceso Under Glass by Lizka, with the author's permission. The author may not see or respond to comments on this post. You can see the original post here.

Tl;dr: being easy to argue with is a virtue, separate from being correct.

Introduction

Regular readers of my blog know of my epistemic spot check series, where I take claims (evidential or logical) from a work of nonfiction and check to see if they’re well supported. It’s not a total check of correctness: the goal is to rule out things that are obviously wrong/badly formed before investing much time in a work, and to build up my familiarity with its subject.

Before I did epistemic spot checks, I defined an easy-to-read book as, roughly, imparting an understanding of its claims with as little work from me as possible. After epistemic spot checks, I started defining easy to read as “easy to epistemic spot check”. It should be as easy as possible (but no easier) to identify what claims are load-bearing to a work’s conclusions, and figure out how to check them. This is separate from correctness: things can be extremely legibly wrong. The difference is that when something is legibly wrong someone can tell you why, often quite simply. Illegible things just sit there at an unknown level of correctness, giving the audience no way to engage.

There will be more detailed examples later, but real quick: “The English GDP in 1700 was $890324890. I base this on $TECHNIQUE interpretation of tax records, as recorded in $REFERENCE” is very legible (although probably wrong, since I generated the number by banging on my keyboard). “Historically, England was rich” is not. “Historically, England was richer than France” is somewhere in-between.

“It was easy to apply this blog post format I made up to this book” is not a good name, so I’ve taken to calling the collection of traits that make things easy to check “epistemic legibility”, in the James C. Scott sense of the word legible. Legible works are (comparatively) easy to understand, they require less external context, their explanations scale instead of needing to be tailored for each person. They’re easier to productively disagree with, easier to partially agree with instead of forcing a yes or no, and overall easier to integrate into your own models.

[Like everything in life, epistemic legibility is a spectrum, but I’ll talk about it mostly as a binary for readability’s sake]

When people talk about “legible” in the Scott sense they often mean it as a criticism, because pushing processes to be more legible cuts out illegible sources of value. One of the reasons I chose the term here is that I want to be very clear about the costs of legibility and the harms of demanding it in excess. But I also think epistemic legibility leads people to learn more correct things faster and is typically underprovided in discussion.

If I hear an epistemically legible argument, I have a lot of options. I can point out places I think the author missed data that impacts their conclusion, or made an illogical leap. I can notice when I know of evidence supporting their conclusions that they didn’t mention. I can see implications of their conclusions that they didn’t spell out. I can synthesize with other things I know, that the author didn’t include.

If I hear an illegible argument, I have very few options. Perhaps the best case scenario is that it unlocks something I already knew subconsciously but was unable to articulate, or needed permission to admit. This is a huge service! But if I disagree with the argument, or even just find it suspicious, my options are kind of crap. I write a response of equally low legibility, which is unlikely to improve understanding for anyone. Or I could write up a legible case for why I disagree, but that is much more work than responding to a legible original, and often more work than went into the argument I’m responding to, because it’s not obvious what I’m arguing against. I need to argue against many more things to be considered comprehensive. If you believe Y because of X, I can debate X. If you believe Y because …:shrug:… I have to imagine every possible reason you could do so, counter all of them, and then still leave myself open to something I didn’t think of. Which is exhausting.

I could also ask questions, but the more legible an argument is, the easier it is to know what questions matter and the most productive way to ask them.

I could walk away, and I am in fact much more likely to do that with an illegible argument. But that ends up creating a tax on legibility because it makes one easier to argue with, which is the opposite of what I want.

Not everything should be infinitely legible. But I do think more legibility would be good on most margins, that choices of the level of legibility should be made more deliberately, and that we should treat highly legible and illegible works more differently than we currently do. I’d also like a common understanding of legibility so that we can talk about its pluses and minuses, in general or for a particular piece.

This is pretty abstract and the details matter a lot, so I’d like to give some better examples of what I’m gesturing at. In order to reinforce the point that legibility and correctness are orthogonal; this will be a four quadrant model.

True and Legible

Picking examples for this category was hard. No work is perfectly true and perfectly legible, in the sense of being absolutely impossible to draw an inaccurate conclusion from and having no possible improvements to legibility, because reality is very complicated and communication has space constraints. Every example I considered, I could see a reason someone might object to it. And the things that are great at legibility are often boring. But it needs an example so…

Acoup

Bret Devereaux over at Acoup consistently writes very interesting history essays that I found both easy to check and mostly true (although with some room for interpretation, and not everyone agrees). Additionally, a friend of mine who is into textiles tells me his textile posts were extremely accurate. So Devereaux does quite well on truth and legibility, despite bringing a fair amount of emotion and strong opinions to his work.

As an example, here is a paragraph from a post arguing against descriptions of Sparta as a highly equal society.

But the final word on if we should consider the helots fully non-free is in their sanctity of person: they had none, at all, whatsoever. Every year, in autumn by ritual, the five Spartan magistrates known as the ephors (next week) declared war between Sparta and the helots – Sparta essentially declares war on part of itself – so that any spartiate might kill any helot without legal or religious repercussions (Plut. Lyc. 28.4; note also Hdt. 4.146.2). Isocrates – admittedly a decidedly anti-Spartan voice – notes that it was a religious, if not legal, infraction to kill slaves everywhere in Greece except Sparta (Isoc. 12.181). As a matter of Athenian law, killing a slave was still murder (the same is true in Roman law). One assumes these rules were often ignored by slave-holders of course – we know that many such laws in the American South were routinely flouted. Slavery is, after all, a brutal and inhuman institution by its very nature. The absence of any taboo – legal or religious – against the killing of helots marks the institution as uncommonly brutal not merely by Greek standards, but by world-historical standards.

Here we have some facts on the ground (Spartiates could kill their slaves, killing slaves was murder in most contemporaneous societies), sources for some but not all of them (those parentheticals are highly readable if you’re a classicist, and workable if you’re not), the inference he drew from them (Spartans treated their slaves unusually badly), and the conclusions he drew from that (Sparta was not only inequitable, it was unusually inequitable even for its time and place).

Notably, the entire post relies heavily on the belief that slavery is bad, which Devereaux does not bother to justify. That’s a good choice because it would be a complete waste of time for modern audiences – but it also makes this post completely unsuitable for arguing with anyone who disagreed. If for some reason you needed to debate the ethics of slavery, you need work that makes a legible case for that claim in particular, not work that takes it as an axiom.

Exercise for Mood and Anxiety

A few years ago I ESCed Exercise for Mood and Anxiety, a book that aims to educate people on how exercise can help their mental health and then give them the tools to do so. It did really well at the former: the logic was compelling and the foundational evidence was well cited and mostly true (although exercise science always has wide error bars). But out of 14 people who agreed to read the book and attempt to exercise more, only three reported back to me and none of them reported an increase in exercise. So EfMaA is true and epistemically legible, but nonetheless not very useful.

True but Epistemically Illegible

You Have About Five Words is a poetic essay from Ray Arnold. The final ~paragraph is as follows:

If you want to coordinate thousands of people…

You have about five words.

This has ramifications on how complicated a coordinated effort you can attempt.

What if you need all that nuance and to coordinate thousands of people? What would it look like if the world was filled with complicated problems that required lots of people to solve?

I guess it’d look like this one.

I think the steelman of its core claim, that humans are bad at remembering long nuanced writing and the more people you are communicating with, the more you need to simplify your writing, is obviously true. This is good, because Ray isn’t doing crap to convince me of it. He cites no evidence and gives no explanation of his logic. If I thought nuance increased with the number of readers I would have nothing to say other than “no you’re wrong” or write my own post from scratch, because he gives no hooks to refute. If someone tried to argue that you get ten words rather than five, I would think they were missing the point. If I thought he had the direction right but got the magnitude of the effect wrong enough that it mattered (and he was a stranger rather than a friend), I would not know where to start the discussion.

[Ray gets a few cooperation points back by explicitly labeling this as poetry, which normally I would be extremely happy about, but it weakened its usefulness as an example for this post so right this second I’m annoyed about it.]

False but Epistemically Legible

Mindset

I think Carol Dweck’s Mindset and associated work is very wrong, and I can produce large volumes on specific points of disagreement. This is a sign of a work that is very epistemically legible: I know what her cruxes are, so I can say where I disagree. For all the shit I’ve talked about Carol Dweck over the years, I appreciate that she made it so extraordinarily easy to do so, because she was so clear on where her beliefs came from.

For example, here’s a quote from Mindset

All children were told that they had performed well on this problem set: “Wow, you did very well on these problems. You got [number of problems] right. That’s a really high score!” No matter what their actual score, all children were told that they had solved at least 80% of the problems that they answered.

Some children were praised for their ability after the initial positive feedback: “You must be smart at these problems.” Some children were praised for their effort after the initial positive feedback: “You must have worked hard at these problems.” The remaining children were in the control condition and received no additional feedback.

And here’s Scott Alexander’s criticism

This is a nothing intervention, the tiniest ghost of an intervention. The experiment had previously involved all sorts of complicated directions and tasks, I get the impression they were in the lab for at least a half hour, and the experimental intervention is changing three short words in the middle of a sentence.

And what happened? The children in the intelligence praise condition were much more likely to say at the end of the experiment that they thought intelligence was more important than effort (p < 0.001) than the children in the effort condition. When given the choice, 67% of the effort-condition children chose to set challenging learning-oriented goals, compared to only 8% (!) of the intelligence-condition. After a further trial in which the children were rigged to fail, children in the effort condition were much more likely to attribute their failure to not trying hard enough, and those in the intelligence condition to not being smart enough (p < 0.001). Children in the intelligence condition were much less likely to persevere on a difficult task than children in the effort condition (3.2 vs. 4.5 minutes, p < 0.001), enjoyed the activity less (p < 0.001) and did worse on future non-impossible problem sets (p…you get the picture). This was repeated in a bunch of subsequent studies by the same team among white students, black students, Hispanic students…you probably still get the picture.

Scott could make those criticisms because Dweck described her experiment in detail. If she’d said “we encouraged some kids and discouraged others”, there would be a lot more ambiguity.

Meanwhile, I want to criticize her for lying to children. Messing up children’s feedback system creates the dependencies on adult authorities that lead to problems later in life. This is extremely bad even if it produces short-term improvements (which it doesn’t). But I can only do this with confidence because she specified the intervention.

The Fate of Rome

This one is more overconfident than false. The Fate of Rome laid out very clearly how they were using new tools for recovering meteorological data to determine the weather 2000 years ago, and using that to analyze the Roman empire. Using this new data, it concludes that the peak of Rome was at least partially caused by a prolonged period of unusually good farming weather in the Mediterranean, and that the collapse started or was worsened when the weather began to regress to the mean.

I looked into the archeometeorology techniques and determined that they, in my judgement, had wider confidence intervals than the book indicated, which undercut the causality claims. I wish the book had been more cautious with its evidence, but I really appreciate that they laid out their reasoning so clearly, which made it really easy to look up points I might disagree with them on.

False and Epistemically Illegible

Public Health and Airborne Pathogen Transmission

I don’t know exactly what the CDC’s or WHO’s current stance is on breathing-based transmission of covid, and I don’t care, because they were so wrong for so long in such illegible ways.

When covid started, the CDC and WHO’s story was that it couldn’t be “airborne”, because the viral particle was > 5 microns. That phrasing was already anti-legible for material aimed at the general public, because airborne has a noticeably different definition in virology (”can persist in the air indefinitely”) than it does for popular use (”I can catch this through breathing”). But worse than that, they never provided any justification for the claim. This was reasonable for posters, but not everything was so space constrained, and when I looked in February 2021 I could not figure out where the belief that airborne transmission was rare was coming from. Some researcher eventually spent dozens to hundreds of hours on this and determined the 5 micron number probably came from studies of tuberculosis, which for various reasons needs to get deeper in the lungs than most pathogens and thus has stronger size constraints. If the CDC had pointed to their sources from the start we could have determined the 5 micron limit was bullshit much more easily (the fact that many relevant people accepted it without that proof is a separate issue).

When I wrote up the Carol Dweck example, it was easy. I’m really confident in what Carol Dweck believed at the time of writing Mindset, so it’s really easy to describe why I disagree. Writing this section on the CDC was harder, because I cannot remember exactly what the CDC said and when they said it; a lot of the message lived in implications; their statements from early 2020 are now memory holed and while I’m sure I could find them on archive.org, it’s not really going to quiet the nagging fear that someone in the comments is going to pull up a different thing they said somewhere else that doesn’t say exactly what I claimed they said, or that I view as of a piece with what I cited but both statements are fuzzy enough that it would be a lot of work to explain why I think the differences are immaterial….

That fear and difficulty in describing someone’s beliefs is the hallmark of epistemic illegibility. The wider the confidence interval on what someone is claiming, the more work I have to do to question it.

And More…

The above was an unusually legible case of illegibility. Mostly illegible and false arguments don’t feel like that. They just feel frustrating and bad and like the other person is wrong but it’s too much work to demonstrate how. This is inconveniently similar to the feeling when the other person is right but you don’t want to admit it. I’m going to gesture some more at illegibility here, but it’s inherently an illegible concept so there will be genuinely legible (to someone) works that resemble these points, and illegible works that don’t.

Marks of probable illegibility:

- The person counters every objection raised, but the counters aren’t logically consistent with each other.

- You can’t nail down exactly what the person actually believes. This doesn’t mean they’re uncertain – saying “I think this effect is somewhere between 0.1x and 10000x” is very legible, and sometimes the best you can do given the data. It’s more that they imply a narrow confidence band, but the value that band surrounds moves depending on the subargument. Or they agree they’re being vague but they move forward in the argument as if they were specific.

- Motte and Bailey is a subtype of this.

- You feel like you understand the argument and excitedly tell your friends. When they ask obvious questions you have no answer or explanation.

A good example of illegibly bad arguments that are specifically trying to ape legibility are a certain subset of alt-medicine advertisements. They start out very specific, with things like “there are 9804538905 neurons in your brain carrying 38923098 neurotransmitters”, with rigorous citations demonstrating those numbers. Then they introduce their treatment in a way that very strongly implies it works with those 38923098 transmitters but not, like, what it does to them or why we would expect that to have a particular effect. Then they wrap it up with some vague claims about wellness, so you’re left with the feeling you’ll definitely feel better if you take their pill, but if you complain about any particular problem it did not fix they have plausible deniability.

[Unfortunately the FDA’s rules around labeling encourage this illegibility even for products that have good arguments and evidence for efficacy on specific problems, so the fact that a product does this isn’t conclusive evidence it’s useless.]

Bonus Example: Against The Grain

The concept of epistemic legibility was in large part inspired by my first attempt at James C. Scott’s Against the Grain (if that name seems familiar: Scott also coined “legibility” in the sense in which I am using it), whose thesis is that key properties of grains (as opposed to other domesticates) enabled early states. For complicated reasons I read more of AtG without epistemic checking than I usually would, and then checks were delayed indefinitely, and then covid hit, and then my freelancing business really took off… the point is, when I read Against the Grain in late 2019, it felt like it was going to be the easiest epistemic spot check I’d ever done. Scott was so cooperative in labeling his sources, claims, and logical conclusions. But when I finally sat down to check his work, I found serious illegibilities.

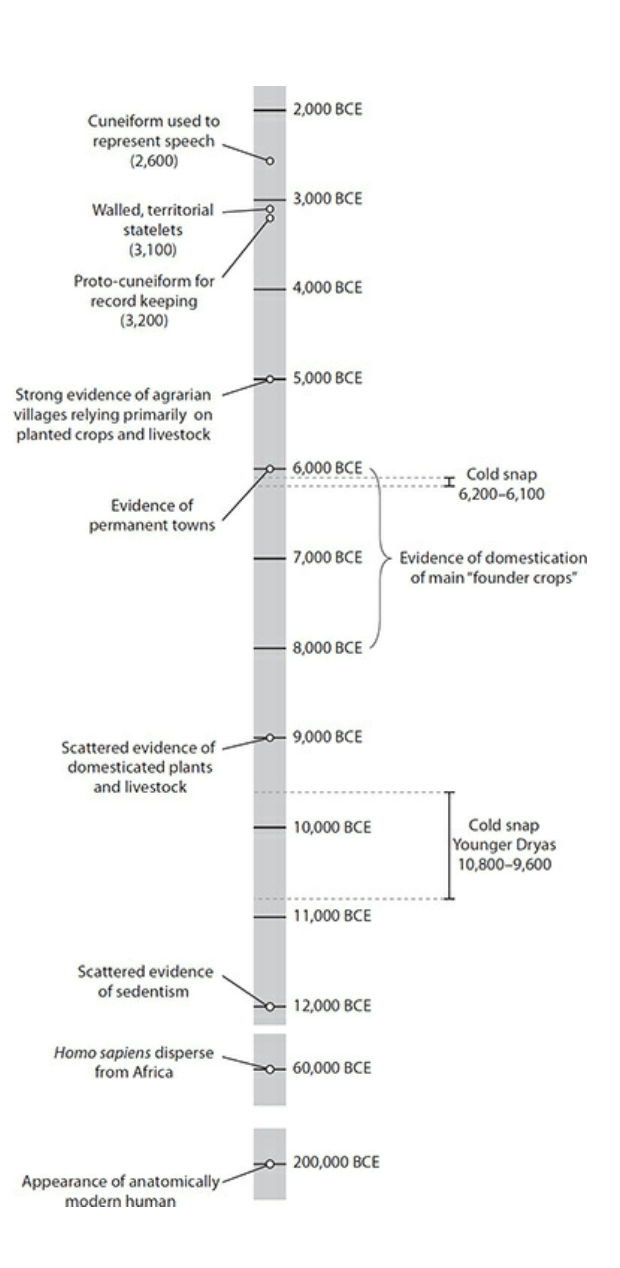

I did the spot check over Christmas this year (which required restarting the book). It was maybe 95% as good as I remembered, which is extremely high. At chapter 4 (which is halfway through the book, due to the preface and introduction), I felt kinda overloaded and started to spot check some claims (mostly factual – the logical ones all seemed to check out as I read them). A little resentfully, I checked this graph.

This should have been completely unnecessary, Scott is a decent writer and scientist who was not going to screw up basic dates. I even split the claims section of the draft into two sections, “Boring” and “Interesting”, because I obviously wasn’t going to come up with anything checking names and dates and I wanted that part to be easy to skip.

I worked from the bottom. At first, it was a little more useful than I expected – a major new interpretation of the data came out the same year the book was published, so Scott’s timing on anatomically modern humans was out of date, but not in a way that reflected poorly on him.

Finally I worked my way up to “first walled, territorial state”. Not thinking super hard, I googled “first walled city”, and got a date 3000 years before the one Scott cites. Not a big deal, he specified state, not walls. What can I google to find that out? “Earliest state”, obviously, and the first google hit does match Scott’s timing, but… what made something a state, and how can we assess those traits from archeological records? I checked, and nowhere in the preface, introduction, or first three chapters was “state” defined. No work can define every term it uses, but this is a pretty important one for a book whose full title is Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States.

You might wonder if “state” had a widespread definition such that it didn’t need to be defined. I think this is not the case for a few reasons. First, Against The Grain is aimed at a mainstream audience, and that requires defining terms even if they’re commonly known by experts. Second, even if a reader knew the common definition of what made a state, how you determine whether something was a state or merely a city from archeology records is crucial for understanding the inner gears of the book’s thesis. Third, when Scott finally gives a definition, it’s not the same as the one on wikipedia.

[longer explanation] Among these characteristics, I propose to privilege those that point to territoriality and a specialized state apparatus: walls, tax collection, and officials.

Against the Grain

States are minimally defined by anthropologist David S. Sandeford as socially stratified and bureaucratically governed societies with at least four levels of settlement hierarchy (e.g., a large capital, cities, villages, and hamlets)

Wikipedia (as of 2021-12-26)

These aren’t incompatible, but they’re very far from isomorphic. I expect that even though there’s a fairly well accepted definition of state in the relevant field(s), there are disputed edges that matter very much for this exact discussion, in which Scott views himself as pushing back against the commonly accepted narrative.

To be fair, the definition of state was not that relevant to chapters 1-3, which focus on pre-state farming. Unless, you know, your definition of “state” differs sufficiently from his.

Against The Grain was indeed very legible in other ways, but loses basically all of its accrued legibility points and more for not making even a cursory definition of a crucial term in the introduction, and for doing an insufficient job halfway through the book.

This doesn’t mean the book is useless, but it does mean it was going to be more work to extract value from than I felt like putting in on this particular topic.

Why is this Important?

First of all, it’s costing me time.

I work really hard to believe true things and disbelieve false things, and people who argue illegibly make that harder, especially when people I respect treat arguments as more proven than their level of legibility allows them to be. I expect having a handle with which to say “no I don’t have a concise argument about why this work is wrong, and that’s a fact about the work” to be very useful.

More generally, I think there’s a range of acceptable legibility levels for a given goal, but we should react differently based on which legibility level the author chose, and that arguments will be more productive if everyone involved agrees on both the legibility level and on the proper response to a given legibility level. One rule I have is that it’s fine to declare something a butterfly idea and thus off limits to sharp criticism, but that inherently limits the calls to action you can make based on that idea.

Eventually I hope people will develop some general consensus around the rights and responsibilities of a given level of legibility, and that this will make arguments easier and more productive. Establishing those rules is well beyond the scope of this post.

Legibility vs Inferential Distance

You can’t explain everything to everyone all of the time. Some people are not going to have the background knowledge to understand a particular essay of yours. In cases like this, legibility is defined as “the reader walks away with the understanding that they didn’t understand your argument”. Illegibility in this case is when they erroneously think they understand your argument. In programming terms, it’s the difference between a failed function call returning a useful error message (legible), versus failing silently (illegible).

A particularly dangerous way this can occur is when you’re using terms of art (meaning: words or phrases that have very specific meanings within a field) that are also common English words. You don’t want someone thinking you’re dismissing a medical miracle because you called it statistically insignificant, or invalidating the concept of thought work because it doesn’t apply force to move an object.

Cruelly, misunderstanding becomes more likely the more similar the technical definition is to the English definition. I watched a friend use the term “common knowledge” to mean “everyone knows that everyone knows, and everyone knows that everyone knows… and that metaknoweldge enables actions that wouldn’t be possible if it was merely true that everyone knew and thought they were the only one, and those additional possible actions are extremely relevant to our current conversation” to another friend who thought “common knowledge” meant “knowledge that is common”, and had I not intervened the ensuing conversation would have been useless at best.

Costs of Legibility

The obvious ones are time and mental effort, and those should not be discounted. Given a finite amount of time, legibility on one work trades off against another piece being produced at all, and that may be the wrong call.

A second is that legibility can make things really dry. Legibility often means precision, and precision is boring, especially relative to work optimized to be emotionally activating.

Beyond that, legibility is not always desirable. For example, unilateral legibility in an adversarial environment makes you vulnerable, as you’re giving people the keys to the kingdom of “effective lies to tell you”.

Lastly, premature epistemic legibility kills butterfly ideas, which are beautiful and precious and need to be defended until they can evolve combat skills.

How to be Legible

This could easily be multiple posts, I’m including a how-to section here more to help convey the concept of epistemic legibility than write a comprehensive guide to how to do it. The list is not a complete list, and items on it can be faked. I think a lot of legibility is downstream of something harder to describe. Nonetheless, here are a few ways to make yourself more legible, when that is your goal.

- Make it clear what you actually believe.

- Watch out for implicit quantitative estimates (“probably”, “a lot”, “not very much”) and make them explicit, even if you have a very wide confidence interval. The goals here are twofold: the first is to make your thought process explicit to you. The second is to avoid confusion – people can mean different things by “many”, and I’ve seen some very long arguments suddenly resolve when both sides gave actual numbers.

- Make clear the evidence you are basing your beliefs on.

- This need not mean “scientific fact” or “RCT”. It could be “I experienced this a bunch in my life” or “gut feeling” or “someone I really trust told me so”. Those are all valid reasons to believe things. You just need to label them.

- Make that evidence easy to verify.

- More accessible sources are better.

- Try to avoid paywalls and $900 books with no digital versions.

- If it’s a large work, use page numbers or timestamps to the specific claim, removing the burden to read an entire book to check your work (but if your claim rests on a large part of the work, better to say that than artificially constrict your evidence)

- One difficulty is when the evidence is in a pattern, and no one has rigorously collated the data that would let you demonstrate it. You can gather the data yourself, but if it takes a lot of time it may not be worth it.

- In times past, when I wanted to refer to a belief I had in a blog post but didn’t have a citation for it, I would google the belief and link to the first article that came up. I regret this. Just because an article agrees with me doesn’t mean it’s good, or that its reasoning is my reasoning. So one, I might be passing on a bad argument. Two, I know that, so if someone discredits the linked article it doesn’t necessarily change my mind, or even create in me a feeling of obligation to investigate. I now view it as more honest to say “I believe this but only vaguely remember the reasons why”, and if it ends up being a point of contention I can hash it out later.

- More accessible sources are better.

- Make clear the logical steps between the evidence and your final conclusion.

- Use examples. Like, so many more examples than you think. Almost everything could benefit from more examples, especially if you make it clear when they’re skippable so people who have grokked the concept can move on.

- It’s helpful to make clear when an example is evidence vs when it’s a clarification of your beliefs. The difference is if you’d change your mind if the point was proven false: if yes, it’s evidence. If you’d say “okay fine, but there are a million other cases where the principle holds”, it’s an example. One of the mistakes I made with early epistemic spot checks was putting too much emphasis on disproving examples that weren’t actually evidence.

- Decide on an audience and tailor your vocabulary to them.

- All fields have words that mean something different in the field than in general conversation, like “work”, “airborne”, and “significant”. If you’re writing within the field, using those terms helps with legibility by conveying a specific idea very quickly. If you’re communicating outside the field, using such terms without definition hinders legibility, as laypeople misapply their general knowledge of the English language to your term of art and predictably get it wrong. You can help on the margins by defining the term in your text, but I consider some uses of this iffy.

- The closer the technical definition of a term is to its common usage, the more likely this is to be a problem because it makes it much easier for the reader to think they understand your meaning when they don’t.

- At first I wanted to yell at people who use terms of art in work aimed at the general population, but sometimes it’s unintentional, and sometimes it’s a domain expert who’s bad at public speaking and has been unexpectedly thrust onto a larger stage, and we could use more of the latter, so I don’t want to punish people too much here. But if you’re, say, a journalist who writes a general populace book but uses an academic term of art in a way that will predictably be misinterpreted, you have no such excuse and will go to legibility jail.

- A skill really good interviewers bring to the table is recognizing terms of art that are liable to confuse people and prompting domain experts to explain them.

- All fields have words that mean something different in the field than in general conversation, like “work”, “airborne”, and “significant”. If you’re writing within the field, using those terms helps with legibility by conveying a specific idea very quickly. If you’re communicating outside the field, using such terms without definition hinders legibility, as laypeople misapply their general knowledge of the English language to your term of art and predictably get it wrong. You can help on the margins by defining the term in your text, but I consider some uses of this iffy.

- Write things down, or at least write down your sources. I realize this is partially generational and Gen Z is more likely to find audio/video more accessible than written work, and accessibility is part of legibility. But if you’re relying on a large evidence base it’s very disruptive to include it in audio and very illegible to leave it out entirely, so write it down.

- Follow all the rules of normal readability – grammar, paragraph breaks, no run-on sentences, etc.

A related but distinct skill is making your own thought process legible. John Wentworth describes that here.

Synthesis

“This isn’t very epistemically legible to me” is a valid description (when true), and a valid reason not to engage. It is not automatically a criticism.

“This idea is in its butterfly stage”, “I’m prioritizing other virtues” or “this wasn’t aimed at you” are all valid defenses against accusations of illegibility as a criticism (when true), but do not render the idea more legible.

“This call to action isn’t sufficiently epistemically legible to the people it’s aimed at” is an extremely valid criticism (when true), and we should be making it more often.

I apologize to Carol Dweck for 70% of the vigor of my criticism of her work; she deserves more credit than I gave her for making it so easy to do that. I still think she’s wrong, though.

Epilogue: Developing a Standard for Legibility

As mentioned above, I think the major value add from the concept of legibility is that it lets us talk about whether a given work is sufficiently legible for its goal. To do this, we need to have some common standards for how much legibility a given goal demands. My thoughts on this are much less developed and by definition common standards need to be developed by the community that holds them, not imposed by a random blogger, so I’ll save my ideas for a different post.

Epilogue 2: Epistemic Cooperation

Epistemic legibility is part of a broader set of skills/traits I want to call epistemic cooperation. Unfortunately, legibility is the only one I have a really firm handle on right now (to the point I originally conflated the concepts, until a few conversations highlighted the distinction- thanks friends!). I think epistemic cooperation, in the sense of “makes it easy for us to work together to figure out the truth” is a useful concept in its own right, and hope to write more about it as I get additional handles. In the meantime, there are a few things I want to highlight as increasing or signalling cooperation in general but not legibility in particular:

- Highlight ways your evidence is weak, related things you don’t believe, etc.

- Volunteer biases you might have.

- Provide reasons people might disagree with you.

- Don’t emotionally charge an argument beyond what’s inherent in the topic, but don’t suppress emotion below what’s inherent in the topic either.

- Don’t tie up brain space with data that doesn’t matter.

Thanks to Ray Arnold, John Salvatier, John Wentworth, and Matthew Graves for discussion on this post.

Thanks for sharing!

Relatedly, there is also the concept of reasoning transparency.