AndrewRowan

Comments8

I have a problem with reports that track all the farmed species, reporting numbers raised on the same chart. In terms of land animals, broiler chicken numbers dwarf pigs, bovines, goats and sheep, and a chart plotting all of them together hides far more than it explains. Now with the advent of insect and shrimp farming, broilers also virtually disappear on a chart plotting invertebrate and vertebrate species together. I can see plotting growth rates for all species on a single chart but only where the farming of a particular species has passed from early explosive growth to a slower growth trajectory. In fact, perhaps analyses of farmed animal populations should identify which species have passed from early-stage explosive growth into a slower growth stage reflecting a maturing industry.

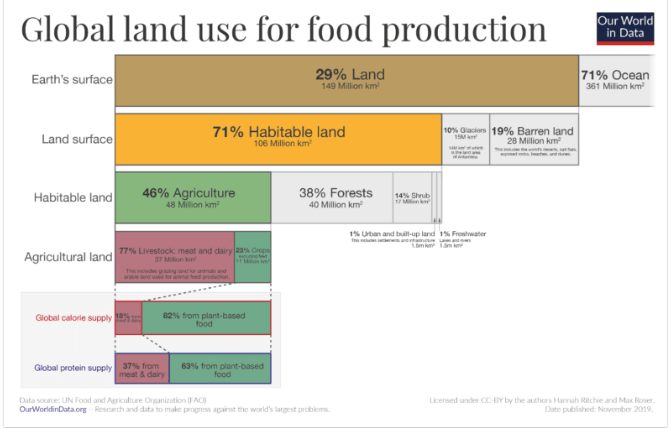

I would also note that the FAO forecasts of 50% or more increases in animal product consumption by humans seldom address where the animal feed to raise twice as many animals might come from. The world currently uses around 70% of arable land to raise food for humans and farmed animals. The world would need to double crop yields per sqkm to produce enough feed for the additional animals. While crop yields are low in some parts of the world, it is hard to discern where the extra feed will come from to raise and slaughter twice as many animals a year!

Andrew Rowan

I agree with many of the points made in the above comment but do not plan to change my vote. When one looks at current expenditures on public health (in the many $trillions of dollars) versus on animal welfare (around $9 billion in revenues annually in the USA), the marginal increase in the utility of grants in the animal welfare space are likely to be greater than those in public health. Open Philanthropy's history project comments on the challenge of producing positive impact in the health space given the large amounts currently devoted annually to support biomedical research let alone the much larger amounts devoted to health treatment, disease surveillance, and prevention.

The marginal effect of increased spending (say $1 billion) on animal welfare is likely to be far greater than the marginal impact of an extra $1 billion on global health. Granted that public health challenges in low and middle-income countries can at times be substantially lessened with relatively small inputs (e.g., niacin enrichment of corn meal), overall, the impact of relatively small amounts of strategically invested money can have a significant impact on the animal space. For example, I believe the support ($1-2 million) Open Philanthropy has provided to Compassion in World Farming to support Compassion's End the Cage Age" citizen's initiative in Europe is going to have substantial global ramifications for how farmed animals are raised and treated down the road. The EU has temporarily stepped back on its commitment to end caged animal farming. Still, the recent Strategic Dialogue on Agriculture in Europe has again emphasized the importance of ending farmed animal cages. I would also refer readers to the recent papers on the impact of the vulture decline in India. The bat decline in the USA (look for documents by Eyal Frank and colleagues), which concluded that the loss of those wild animals has led to substantial increases in all cause human mortality in India and infant mortality in the USA. Calculating the economic impact of biodiversity decline is a significant challenge, but Frank has provided two fascinating and valuable examples of how animal welfare, human welfare and planetary well-being are connected!

The first shareholder case in the USA was the suit filed by Peter Lovenheim of the Humane Society of the U.S. against Iroquois Brands in 1985. The company argued that Foie Gras was too small a part of their business to be the focus of a shareholder lawsuit but the SEC disagreed and held that the shareholder action could proceed.

Andrew Rowan, WellBeing International

The FAO blithely projects a doubling of the population of farmed animals but such a doubling would presumably require a doubling of feedstuffs for those animals. The world is already using half of the available habitable land (71% of all land) and large quantities of ocean animals to feed the existing farmed animal population. If twice as many farmed animals have to be fed, then presumably that would require using all of the habitable land for agriculture (to produce feed for the greater number of animals. That leaves no land for wild animals or forests (or other human needs). This is undoubtedly a simplistic calculation but doubling the number of farmed animals would certainly have disastrous consequences for biodiversity and current land-based carbon sinks.

I would like to see a projection that looks at future animal populations plus the options for feeding those animals from existing land and marine sources.

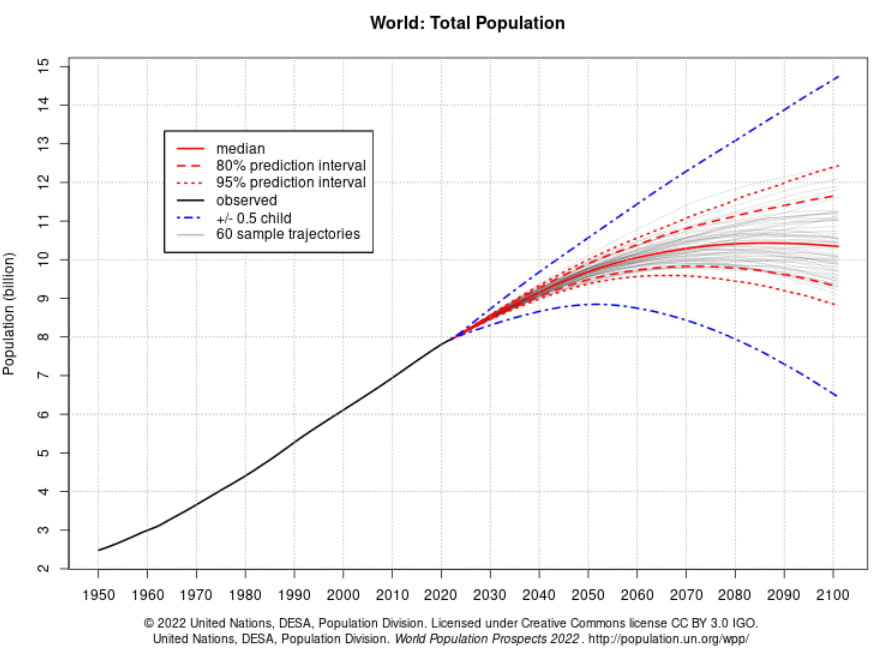

In addition, just because someone projects that the world will reach a particular condition does not mean that such a condition is inevitable. At one point, population scientists projected that the world population would peak at around 12.4 billion people.

However, their projections have fallen. Forecasts now suggest that there will be 8.9 billion people by 2100 (1 billion more than today). That number could be driven even lower if the world was better at preventing a larger portion of unintended pregnancies.

Andrew Rowan, D.Phil.

President, WellBeing International

I empathize with Akash Kulgod's efforts to estimate the owned and street dog population of India. There are no good surveys of the national dog population. The government does publish estimates of the dog population but they are hopelessly wrong. However, there is an interesting method that could produce relatively accurate estimates of India's dog population. It turns out that the relative population of dogs in India (that is the number of dogs per 100 or 1,000 people) varies inversely with human density and one can capture that variation by plotting dogs per 100 (or 1,000) people against log human density in a particular community. For example, a survey in the state of Haryana reported that there were approximately 25 million dogs in the state. The trendline equation for the State of Haryana is y (dogs per 1,000 people) = -100 X (log human density per sqkm) + 440. A survey of dogs in Punjab produced data that gave a trendline equation of y = -32.5 X + 158.4. In Bangalore, the equation is y = - 49 X + 250. In Jamshedpur, the equation is y = -43.6 X + 204. Therefore, it is likely that one could develop a reasonably accurate estimate of the number of dogs in India using a range of human density values and estimates of human populations in different landscapes across India.

However, the Indian pet dog population is currently growing very rapidly and so it may be necessary to undertake a few careful surveys of pet and street dog populations to update the above equations.

Amid the various claims re leadership gaps and animal welfare deficits, it may surprise many that animal protection has seen substantial increases in income over the past fifty years (since the first "animal liberation" article by Peter Singer in 1983. The report on the growth in animal philanthropy on the Animal Grantmakers website tracks some of the animal protection funding developments since the founding of the affinity group in 1999. However, it is not just funding that has grown. In 1980, there were no university-based animal protection programs. Today, there is an undergraduate degree in animal protection (Eastern Kentucky University) and several masters degree programs (Tufts Center for Animals and Public Policy, Canisius College) and multiple animal protection centers at universities around the US (Tufts, UPenn, Canisius, UC Davis, Colorado State, Washington State, University of Tennessee, Arizona State and a number of others). Animal protection is thriving and students are flocking to animal advocacy courses across the USA. In my estimation, animal protection currently spends around $8 billion annually on various aspects of animal advocacy. The movement is not struggling. It is growing rapidly. The only question in my mind is how much further can the movement grow? In Colorado, animal advocacy organizations raise $18 per capita. At the low end, there are state animal advocacy movements that are raising "only" around $3 per capita. Animal advocacy income growth since the turn of the century has increased 3-4 fold in a number of states.

I have not looked at the issue but I suspect that many animal advocacy organizations offer multiple internships to students already. They could probably do more but the challenge is growing such opportunities, not creating a whole new structure.

Andrew Rowan