Ozzie Gooen

Bio

I'm currently researching forecasting and epistemics as part of the Quantified Uncertainty Research Institute.

Posts 92

Comments1168

Topic contributions4

I don't mean to sound too negative on this - I did just say "a bit sad" on that one specific point.

Do I think that CE is doing worse or better overall? It seems like Coefficient has been making a bunch of changes, and I don't feel like I have a good handle on the details. They've also been expanding a fair bit. I'd naively assume that a huge amount of work is going on behind the scenes to hire and grow, and that this is putting CE in a better place on average.

I would expect this (the GCR prio team change) to be some evidence that specific ambitious approaches to GCR prioritization are more limited now. I think there are a bunch of large projects that could be done in this area that would probably take a team to do well, and right now it's not clear who else could do such projects.

Bigger-picture, I personally think GCR prioritization/strategy is under-investigated, but I respect that others have different priorities.

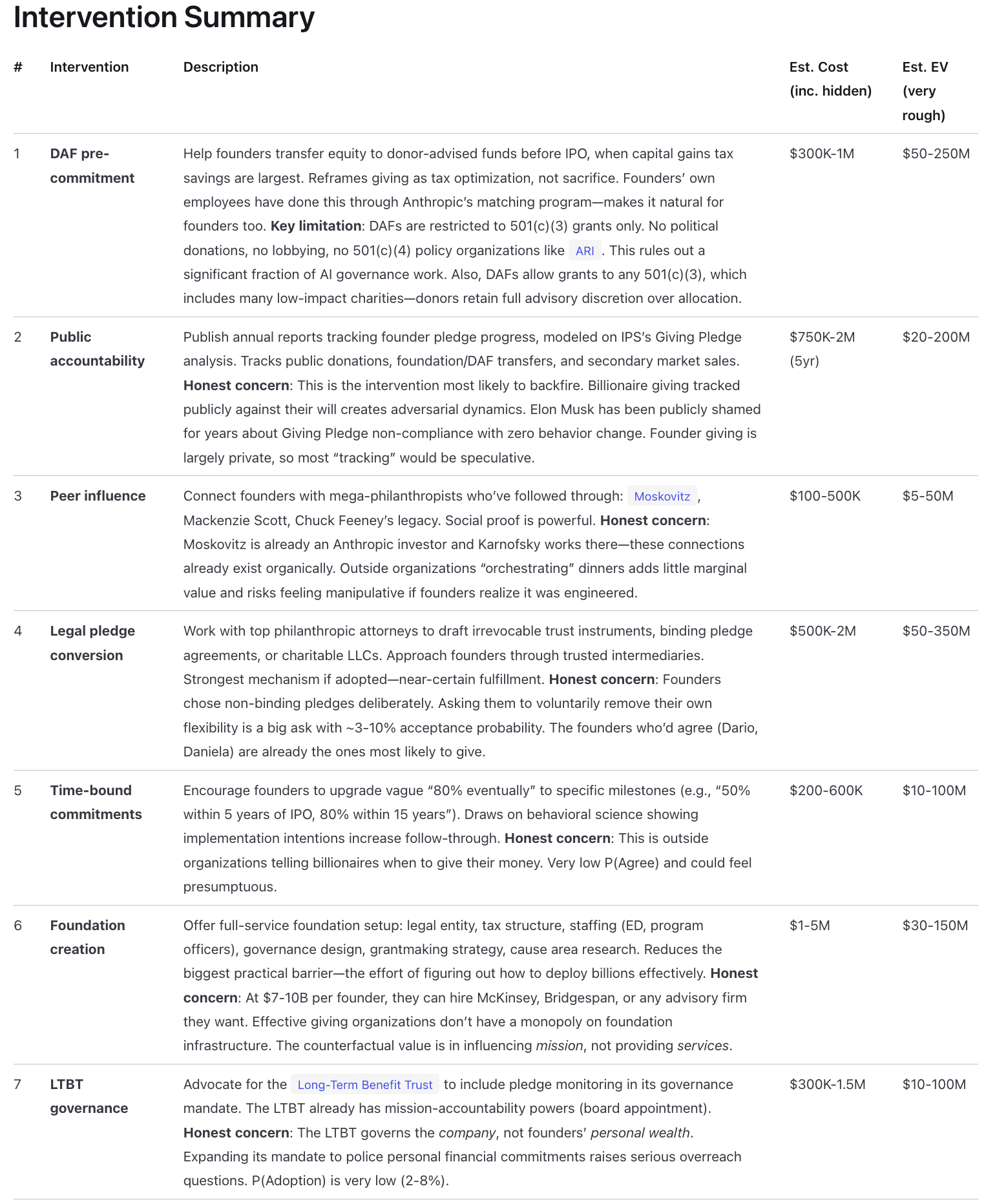

I had my Claude system do some brainstorming work on this.

https://www.longtermwiki.com/knowledge-base/models/intervention-models/anthropic-pledge-enforcement/

It generated some more specific interventions here.

I've been experimenting recently with a longtermist wiki, written fully with LLMs.

Some key decisions/properties:

1. Fully LLM-generated, heavily relying on Claude Code.

2. Somewhat opinionated. Tries to represent something of a median longtermist/EA longview, with a focus on the implications of AI. All pages are rated for "importance".

3. Claude will estimates a lot of percentages and letter grades for things. If you see a percentage or grade, and there's no citation, it might well be a guess by Claude.

4. An emphasis on numeric estimates, models, and diagrams. I had it generate many related models to different topics, some are better than others. Might later take the best ones and convert to Squiggle models or similar.

5. Still early & experimental. This is a bit in-between an official wiki and a personal project of interest now. I expect that things will become more stable over time. For now, expect pages to change locations, and terminology to be sometimes inconsistent, etc.

I overall think this space is pretty exciting right now, but it definitely brings challenges and requires cleverness.

https://www.longtermwiki.com/

https://www.longtermwiki.com/knowledge-base/responses/epistemic-tools/tools/longterm-wiki/

Recently I've been working on some pages about Anthropic and the OpenAI Foundation's potentials for impact.

For example, see:

https://www.longtermwiki.com/knowledge-base/organizations/funders/anthropic-investors/

https://www.longtermwiki.com/knowledge-base/organizations/funders/openai-foundation/

There's also a bunch of information on specific aspects of AI Safety, different EA organizations, and a lot more stuff.

It costs about $3-6 to add a basic page, maybe $10-$30 to do a nicer page. I could easily picture wanting even better later on. Happy to accept requests to add pages for certain organizations/projects/topics/etc that people here might be interested!

Also looking for other kinds of feedback!

I should also flag that one way to use it is through another LLM. Like, ask your local language model to help go through the wiki content for you and summarize the parts of interest.

I plan to write a larger announcement of this on the Forum later.

Quickly:

1. I think there's probably good work to be done here!

2. I think the link you meant to include was https://www.longtermwiki.com/knowledge-base/organizations/funders/giving-pledge/

3. To be clear, I'm not directly writing this wiki. I'm using Claude Code with a bunch of scripts and stuff to put it together. So I definitely recommend being a bit paranoid when it comes to specifics!

That said, I think normally it does a decent job (and I'm looking to improve it!). On the 36%, that seems to have come from this article, which has a bit more, which basically reaffirms the point.

https://ips-dc.org/report-giving-pledge-at-15/

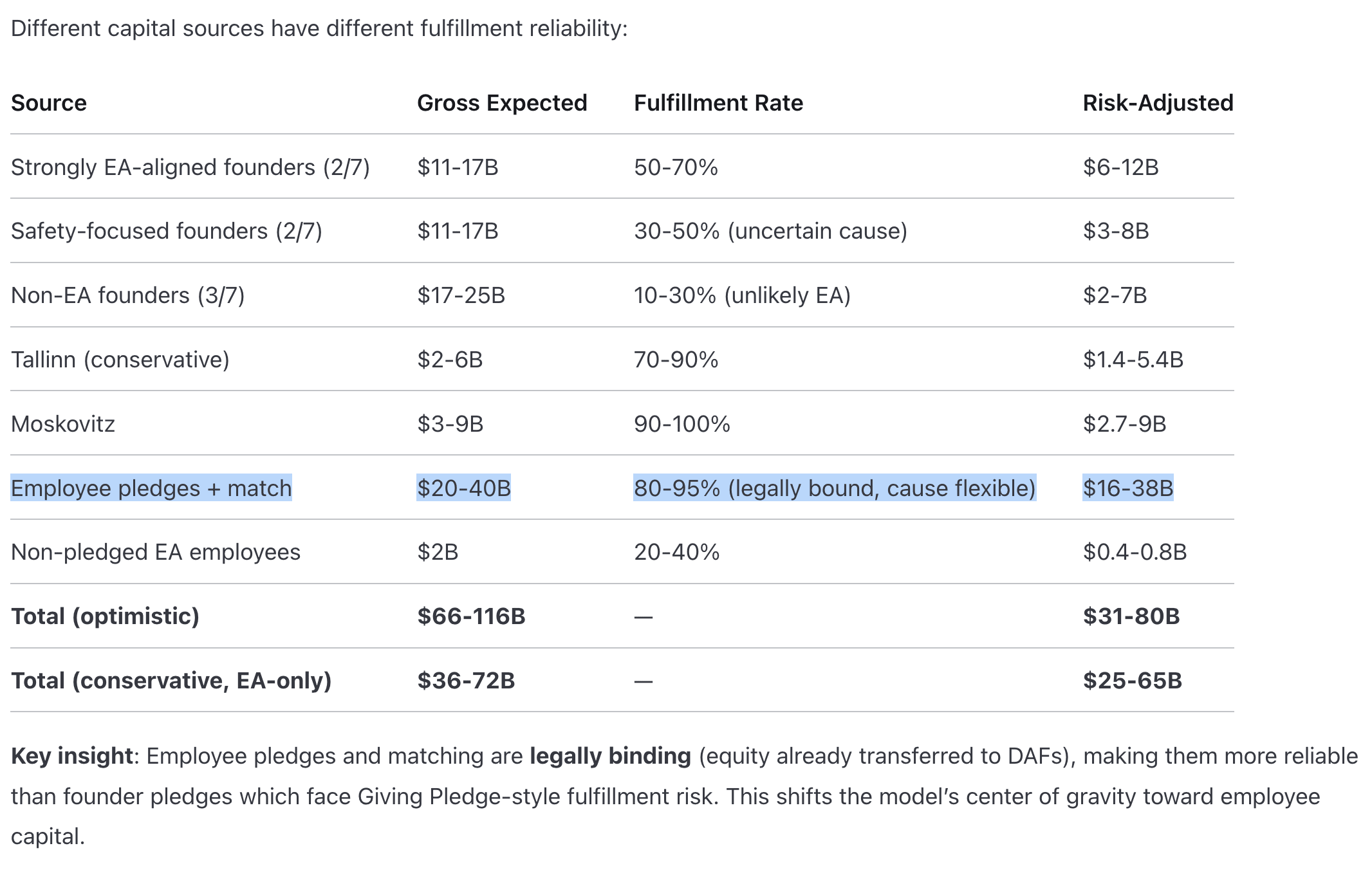

Also, to give Anthropic credit, I want to flag that a bunch of the employee donations are legally binding. Anthropic had a matching program which led to a good amount of money in Donor Advised Funds. https://www.longtermwiki.com/knowledge-base/organizations/funders/anthropic-investors/ (Note that this is also LLM-generated, so meant as a rough guess)

Deceased Pledger pledge fulfillmentWe calculate pledge fulfillment for deceased Pledgers as the amount of a Pledger’s charitable giving (either during their lifetime or through bequests from their estate) divided by the sum of their final net worth plus their charitable giving.

- 22 U.S. Pledgers have died, including 14 of the original 2010 signers. These 22 people were worth a combined $43.4 billion when they died.

- Only one of the 22 deceased Pledgers — Chuck Feeney — gave his entire $8 billion fortune away before he died.

- 8 of the 22 deceased Pledgers fulfilled their pledges, giving away 50 percent or more of their wealth at death, either while they were living or in their estates.

- The remaining 13 deceased Pledgers gave away less than 50 percent of their wealth, either while they were living or in their estates — although some of their estates are still being resolved.

A bit sad to find out that Open Philanthropy’s (now Coefficient Giving) GCR Cause Prioritization team is no more.

I heard it was removed/restructured mid-2025. Seems like most of the people were distributed to other parts of the org. I don't think there were public announcements of this, though it is quite possible I missed something.

I imagine there must have been a bunch of other major changes around Coefficient that aren't yet well understood externally. This caught me a bit off guard.

There don't seem to be many active online artifacts about this team, but I found this hiring post from early 2024, and this previous AMA.

I've known and respected people on both sides of this, and have been frustrated by some of the back-and-forth on this.

On the side of the authors, I find these pieces interesting but very angsty. There's clearly some bad blood here. It reminds me a lot of meat eaters who seem to attack vegans out of irritation more than deliberate logic. [1]

On the other, I've seen some attacks of this group on LessWrong that seemed over-the-top to me.

Sometimes grudges motivate authors to be incredibly productive, so maybe some of this can be useful.

It seems like others find these discussions useful form the votes, but as of now, I find it difficult to take much from them.

[1] I think there are many reasonable meat eaters out there, but there are also many who are angry/irrational about it.

Interesting analysis!

One hypothesis: animal advocacy is a frequent "second favorite" cause area. Many longtermists prefer animal work to global health, but when it comes to their own donations and career choices, they choose longtermism. This resembles voting dynamics where some candidates do well in ranked-choice but poorly in first-past-the-post.

Larks makes a good point - AI risk is also underfunded relative to survey preferences. The bigger anomaly is global health's overallocation.

My very quick guess is that's largely founder effects. I.E. GiveWell's decade-long head start in building donor pipelines and mainstream legibility, while focusing on global health.

I'm not a marketing expert, but naively these headlines don't look great to me.

"Veganuary champion quits to run meat-eating campaign"

"Former Veganuary champion quits to run meat-eating campaign - saying vegan dogma is 'damaging' to goal of reducing animal suffering"

I'd naively expect most readers to just read the headlines, and basically assume, "I guess there's more reasons why meat is fine to eat."

I tried asking Claude (note that it does have my own custom system prompt, which might bias it) if this campaign seemed like a good idea in the first place, and it was pretty skeptical. I'm curious if the FarmKind team did, and what their/your prompt was for this.

I appreciate this write-up, but overall feel pretty uncomfortable about this work. To me the issue was less about the team not properly discussing things with other stakeholders, than it was just the team doing a risky and seemingly poor intervention.

Thanks so much for this response! That's really useful to know. I really appreciate the transparency and clarity here.

Hope that the team members of it are all doing well now.