Many diet change advocates think, explicitly or not, of animal farmers as opponents instead of potential allies. This is ill-advised for a few reasons. Firstly, factory farming is itself an abusive system that harms animals and humans alike — consider how U.S. contract chicken farmers are frequently exploited by big business or how slaughterhouse workers endure some of the poorest welfare standards of any job globally.

Secondly, it’s a strategic blunder. Any group that believes a social change will harm them is going to fight like hell to stop it… including farming groups, who are more than happy to open their wallets to influence legislation. At best, animal farmers can be strong allies, opting to transform their farms into either a plant-based farm or an animal sanctuary (often called a “transfarmation”).

We’d do well to keep farmers’ perspectives top of mind when advocating for meat reduction — so here’s what the research says about their mindsets and motivations.

SubscribeThis is a crosspost from my newsletter on meat reduction, which you can subscribe to (for free!) here:

Farmers Think About Welfare Differently Than You Do

Farmers recognize that their animals are sentient, intelligent, and capable of emotions. This isn’t surprising on its face — anyone who's spent time around animals can recognize their interiority, just ask me about my birds’ many moods! But farmers tend to conceive of animal welfare in practical terms, not emotional or ethical ones. They’re more likely to think about the structure of their cage or the lack of visible injuries rather than access to fresh air or the ability to play with their friends.

“Farmers recognize the emotional and natural living aspects of animals as important but tend to prioritize productivity and biological functioning, especially health, when making practical decisions affecting farm animal welfare.” (Hötzel et. al., 2025)

This mentality isn’t inherently a problem on the surface, but can get messy. As meat demand grows, production intensifies — this is nearly always bad for animal welfare, as more animals are kept in tiny enclosures, given less time outside, and often fattened at a faster rate, leading to health problems. As a result, industrialized countries like the U.S. are seeing fewer and fewer farms every year, which are growing in size.

Research suggests that this intensified production is changing the way that farmers conceptualize welfare. In a study of Brazilian dairy farmers, pastoral farmers linked welfare with the intrinsic needs of cows, like sunshine and open space, while farmers who used more confinement prioritized reducing stressors, increasing comfort, and improving “productivity”. The authors argue convincingly that situational factors drive farmers to view their animals with a more instrumental lens: units of productivity, not individuals.

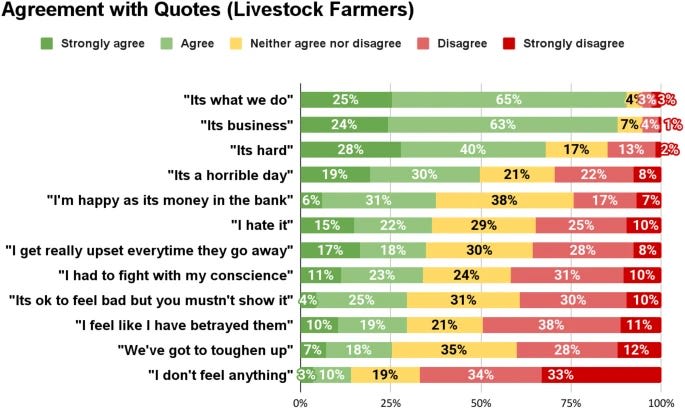

These contradictory views of animal welfare lead to emotional suppression and poor mental health outcomes for many farmers. A 2025 survey of UK animal farmers finds that they use various coping mechanisms when sending animals to slaughter. What’s striking to me is that the most agreed-upon statements are also the most neutral — “it’s what we do,” or “it’s business” — suggesting that farmers are trying to distance themselves emotionally from the slaughter process. Only 13% of farmers stated they don’t feel anything about sending their animals to slaughter.

In a later question, farmers were asked how they thought the rest of the group responded to these questions. Farmers overestimated how many people were “happy with money in the bank” and underestimated “I have to fight it with my conscience.” This suggests that there is a social norm not to express negative feelings regarding animal slaughter. A majority of participants also said they felt mental health was one of the biggest hidden problems in animal farming today — a cause that Vegans Support the Farmers is working on addressing.

However, a 2025 review argues that positive attitudes towards welfare don’t predict improved welfare standards such as cage-free systems or stopping painful castration and tail-docking practices, not to mention reduced herd sizes. In other words, while animal farmers may hold positive views of sentience and welfare and may even emotionally suffer when sending animals to slaughter, they aren’t changing farming practices as a result. Attitudes aren’t predicting behavior…something else is at play.

Money Talks

Okay, it’s money. You probably already knew it was money, but it’s money. Four studies I reviewed found that farmers value economic prosperity when making decisions about the future of their farm, including potential shifts to plant-based agriculture.

The 2025 UK study found that many livestock farmers would consider decreasing their herd size (63%) or shifting away from farming animals entirely (49%) if they could find an economically viable alternative. Another found that profit and economic concerns were the top motivators when making decisions about the future of their farm — environmental concerns were ranked third. A meta-analysis makes a case for why: farmers, like all people, have an attitude-behavior gap. Changing our behavior is hard for everyone, especially when it may be financially risky.

“[...] The expectation of improved economic returns is perhaps the most important factor underlying more positive attitudes and intentions to make investments in animal welfare improvements and voluntarily join animal welfare assurance programs.” (Hötzel et. al., 2025)

That’s why Transfarmation, an organization devoted to farmer transition, focuses on assisting farmers with the economic difficulties of transforming their farm. We can also create more government programs to make the transition easier economically, like how the Netherlands is spending 1.5 billion euros to help livestock farmers transition.

As the number of transformations has grown in recent years, researchers have been examining the motivations of those farmers. We need to note something here: these farmers are not representative of the larger population — in fact, I find it likely that early adopters of this change are likely quite different than the broader farming population. Still, these studies are more likely to find that ethical concerns are more prevalent, with one study even finding that sending animals to slaughterhouses is the act that’s most likely to trigger a transformation. This is encouraging, even if we don’t know how widespread these concerns can be.

Other Motivations At Play

There are other significant barriers to change: feeling that the land was better suited for animal production than plant production, a sense of personal or national identity as an animal farmer, and a historical or ancestral connection with their animal farming methods. To overcome these barriers, farmers need support, both social and practical, to change their farms (to see a detailed analysis of the required support, check out this table from a 2023 study).

Some advocates have argued that societal diet change might incentivize farmers to change their farming style, but that likely won’t be possible for a while, if ever. Most farmers don’t currently consider diet change, veganism, or meat reduction to be a significant threat to their careers.

Climate, on the other hand, is a different beast. Since agriculture is both a cause and a victim of a warming climate, most farmers are aware of climate change, even as they may use unsustainable farming methods. But, according to one 2015 study in the U.S., while most animal farmers believe climate change is occurring (68%), only a minority think it’s primarily because of human action (10%). That’s a problem because the study found that only “those farmers who assign blame to humans see value in societal efforts to reduce GHGs.” However, in recent years, farmers are more likely to believe that climate change is caused by humans (62%) or agriculture (57%), which is good, because this is correlated with wanting to change farming practices.

Still, farmers might support political reform even if they are unwilling to transition themselves — similar to how consumers are more likely to support higher-welfare laws but don’t buy higher-welfare products (the “vote-buy gap” in researcher terms). Farmers are very supportive of policies that fund farmer transition to “climate-smart” agriculture conservation practices. 70% of UK farmers would support government policies to help farmers transition out of animal farming, with 74% even open to alternative protein development or similar practices!

Expanding Our Coalition

Global meat reduction is going to be a hell of a lot easier if farmers are in on the process. We need to create more pathways for animal farmers to employ higher welfare practices, reduce their herd sizes, or transition to plant-based agriculture — this means addressing the very real social and financial barriers they are experiencing. Secondly, we can lobby with farmers for better government programs to create funding for farm transformations. Many of them are already open to the cause! We also should support farmers who experience emotional distress over slaughter — they can be potential allies in the future.

We also need more research. The vast majority of research I could find was interview-based and qualitative, with very few survey-based, messaging RCTs, or other quantitative measures in the mix. This suggests a stark research gap — I think that more messaging research in particular would benefit the global meat reduction movement, as we can improve our outreach with better data.

Overall, I’m surprised by how few non-profit organizations are taking animal farmer collaboration seriously as an intervention. Long term, we’re going to need to work harder on welcoming them into the fold… without them, changing our food systems will only become more difficult.

Executive summary: This exploratory post argues that effective animal advocacy must treat farmers as potential allies rather than adversaries, since their decisions are driven less by attitudes toward animal welfare and more by economic, social, and cultural factors, and collaboration with them could be pivotal for advancing meat reduction and farm transitions.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.