This is the video and transcript of a talk I gave on AI welfare at Anthropic in May 2025. The slides are also available here. The talk gives an overview of my current take on the topic. I'm also in the midst of writing a series of essays of about it, the first of which -- "On the stakes of AI moral status" -- is available here (podcast version, read by the author, here). My takes may evolve as I do more thinking about the issue.

Hi everybody. Thanks for coming. So: this talk is going to be about AI welfare. About whether AIs have welfare, moral status, consciousness, that kind of thing. How to think about that, and what to do in light of reasonable credences about it and ongoing uncertainty.

Plan

I'm going to start by saying thank you to Anthropic for thinking about this. I'm guessing many people saw, there was a few weeks ago a release of a bunch of content from Anthropic about this. I really appreciate that folks are taking it seriously, and so thank you for that.

The aim in this talk: basically I'm just going to talk about how I'm currently thinking about this issue. I started in on this project after going to a conference on AI welfare and I was like, "What do I actually think?" I'd had stored views about this, but I wanted to double click and really come to a considered take.

So I'm going to talk about that, and talk in particular about why I think we should be taking this seriously: why this issue is important, why AIs can probably be conscious in principle, why near-term AIs might be conscious in practice, why consciousness might not be the only place to focus in thinking about this, and then finally, a few takes what to do about it.

And I'll say this is the sort of talk where basically every point is going to be the sort of thing you could talk about for a very long time and have a very long discussion of. Let's hold off on substantive debate until the Q&A, but if you have a clarification question, you're like, "I don't know what that is or I'm confused about that," feel free to jump in on that. The talk is being recorded, but we're going to cut out the Q&A.

What's at stake here?

Okay, so with that said, let's start by just tuning into the stakes of this question. So we have this notion of moral patienthood. It's kind of this technical philosopher's notion. If you just say to someone "are AIs moral patients?" they won't necessarily know what we mean. And do we even know what we mean? I'm not sure.

So I want to start by just trying to tune into more concrete handles on the sort of question we're asking here. Maybe the most direct for me is thinking about my own experiences of pain and suffering. So if you imagine stubbing your toe, right? Now, let's not even use words... Don't even, no words, just what is that? There's something that sucks about stubbing your toe. Who knows if it's consciousness or not, that's too technical. Just: there's something bad about stubbing your toe and I don't want other people to have that bad thing either.

We can think about other experiences of suffering. So really just tuning toward that, just whatever that is. And you can kind of unknow about exactly what you're pointing at. But there's something in pain and suffering that I think is very intuitive that we don't want -- not just for ourselves but for others as well, including the AIs. So that's one handle we can start with.

Another handle is to think about cases where the that feels like it's genuinely uncertain whether that's at stake, right? So if you think about: you're at the dentist and they're about to drill and they're giving you the anesthetic and a little part of you starts to wonder, "Did the anesthetic work? What's about to happen to me?" Right? Okay, so what is that question? There's some stakes to whether or not the anesthetic worked. Something is either going to be there or not. So what's that? What's the difference?

Same with: we have these horrifying cases of patients with locked-in syndrome who are conscious, they're being operated on, they report later that they were there, they were internally screaming. That's another: that. The difference between that happening and someone being unconscious.

Babies. For a long time, people just thought babies weren't conscious and assumed they weren't conscious, operated on babies without anesthetic. Animals, clear case. So that's another way in.

Another one is thinking about attitudes like empathy, love, respect and experience of someone as a thou as opposed to an object. What is that pointed at? What's on the other side of empathy or love or respect? When you treat something with empathy or love or respect, what is the thing such that it feels appropriate to treat it that way? And again, you might be like, "Well, because it's conscious." Well, I'm not sure yet. I'm going to talk later about whether we should be only focusing on consciousness here. But using that as a handle: there's something on the other side of these attitudes and we might not know what that is yet, but there's something there that we care about.

Another way in, there's this movie from Steven Spielberg called A.I. It's got Haley Joel Osment. I think it's a kind of underrated AI movie. I recommend it. It's very weird. And there's a scene in this movie where these robots get captured and they get taken to what's called a flesh fair where there are these humans who destroy robots for sport. So they melt them in acid, they fire them through cannons, the robots are saying goodbye to each other, the humans are jeering from the bleachers. And the main character robot at one point gets taken up and the announcer is saying, "Look at this living doll, this tinker toy. We're only demolishing artificiality," and he's screaming as the acid drips on him.

Okay, so imagine that aliens capture you and take you to a flesh fair of this kind, and the aliens point to you and they say, "Look at this living doll, look at this tinker toy." And you're like, "They're missing something." Right? You want to be like, "I'm not a doll." Okay, so what is it to be not a doll? What is the thing that you're trying to stand up for in yourself when the aliens treat you as a toy?

And then finally, we can think about historical cases where we've gotten something about moral patienthood very deeply wrong. So we can think about slavery, we can think about factory farming, other cases. Obviously it's important if we're getting into the details on that, there's a lot to say about the differences and similarities with AI. I think this is a place we should be clear and cautious, but I think it is something to have in mind when we think about moral patienthood. You can get this really wrong in ways that are some of humanity's greatest sources of shame. So that's a little bit about the stakes.

Some numbers

I think it's also worth saying a little bit more quantitative about the numbers. So currently: it's not clear how to think about the computational capacity of the brain. I did some work on this a while back. I think it's actually a really messy topic. If you treat the brain kind of like an artificial neural network and various other estimates are in the same ballpark, you get something like 1e15 FLOP/s. On that estimate, a frontier training run is already the compute equivalent of more than a thousand years of human experience, which is a long time. If you imagine yourself going through some training process for a thousand years, that's a serious chunk of experience for a human.

Training runs are currently growing 4-5x per year, maybe not sustainable, but that's going up fast. If we got to the point where we were doing the compute equivalent of a million Grok 3 runs per year across inference training, et cetera, there would be more AI cognition than human cognition happening. And the ratios only get more extreme from there. And in the long run, by default, most cognition, I think is likely to be digital. So if that cognition is moral status possessing, then most of the moral status would be digital too. So the eventual stakes here, I think, are very serious.

Over-attribution

Now that said, I think we should also think about the possibility of over-attributing moral status to beings and to AIs.

Candidate real-world cases here include some of them, these are controversial, but you can think about stem cells, you can think about early-stage fetuses, depending on your view, you might think that's a case of over-attribution. We can also talk about literal cases in which humans seem inclined to over-attribute to AIs. We can talk about Blake LeMoine, we can talk about people being very easily slipped into seeing very simple chatbots as kind of sentient or agent-like. And then more fancily, we can talk about cases like: suppose maybe you don't cure cancer because what if your pipettes are moral patients or your petri dishes or something like that. So you have some concern and you throw away some really concrete benefit for the sake of some esoteric concern about moral patienthood.

And then we can talk about more extreme cases in the real world. So in particular, increasing other sources of risk from AI and harm from AI or delaying really serious benefits from AI in virtue of a false or sloppy picture of AI welfare. And I think these stakes are very real too. I think it can seem kind of easy to talk about, "Oh, the precautionary principle, lets..." And it can also seem kind of virtuous to be very profligate with your care. And I think there's a sense in which that's true and there's a place for that. But I also think we should be trying to get this actually right and we should be trying to benefit as much as we can from what knowledge we have and trying to have our credences actually reflect the true situation so we can make trade-offs here in the right way.

I'll also say there are theories of things like consciousness that are very profligate about which beings have them. So panpsychists think that everything has some amount of consciousness. I don't think that helps. Basically at that point, you just need a new theory of over-attribution, right? So you're in a fire and there's a baby and there's two teddy bears, right? Maybe you think the teddy bears are conscious in some sense, but you still need some story about why you should save the baby. Or: I claim you should save the baby. And I claim that if you don't save the baby, if you save the teddy bears, then that's a type of over-attribution, you're giving something to the teddy bears that they don't have, or you likely are. So those are a few comments about the stakes.

Consciousness

Now let's talk a little bit about consciousness. So by far the most intuitive condition for mortal patienthood is consciousness. If you talk to people about AI welfare, the quickest way in is just to be like, "Are the AIs conscious?" And this was the theme of Anthropic's recent content on this.

Specifically the type of consciousness I have in mind here is phenomenal consciousness, what it's like, subjective experience, et cetera. And that's a sort of esoteric definition. You can also talk about definition by example. So you can talk about canonically conscious experiences like pain, red, joy, that kind of thing, and then you can talk about, okay, what's the most natural thing that those canonical experiences have and rocks, digestion, tables don't have we think, right? And that's another way of defining it. It takes some stand on things like panpsychism, but it's another way in.

And I think a mistake to not make in this context is to dismiss the consciousness of beings that you're conceiving of mechanistically. This is a sort of known trait of human thinking about consciousness that when you think about something from a kind of mechanistic perspective, it doesn't seem conscious, and people will often do this with AIs. They'll sort of be like, "Oh, the AI is just a GPU, it's just a matrix multiplication, it's just something," and you have some picture of this "just" and then it doesn't seem conscious conceived of that way.

The problem is that that way of conceiving of things gives the wrong result for the human brain. So if you imagine you're Ms. Frizzle and you shrink yourself down in your magic school bus and you go explore the human brain, you see all these neurons and it's like, where's the consciousness? Where's the red? There's no red in there. It's not red, there's no pain. So there's a sense in which you can apply that same sort of logic, "Oh, the brain is just neurons." We got to be really careful with that word "just," and so we need something other than this kind of argument for thinking about AIs.

Unfortunately, consciousness is just famously the most... it's just an incredibly mysterious, difficult thing to think about, it's probably the biggest kind of ongoing mystery in our fundamental conception of the universe. Which is a shame. It's a real shame that that is also plausibly the source of most or all moral value, that these things came together. Is that a coincidence? I'm not sure. But it's rough.

Regardless though, we got to deal with it. There's a lot of uncertainty. So obviously this is going to be a game about credences. The thing to think about when you're doing AI welfare is definitely not to be like, "All right, first I'm going to solve consciousness and then I'm going to apply that solution to the AI." As much as many people I know seem to be taking this approach, we're not going to solve consciousness. The game is to have reasonable takes on it and to act reasonably in light of our uncertainty.

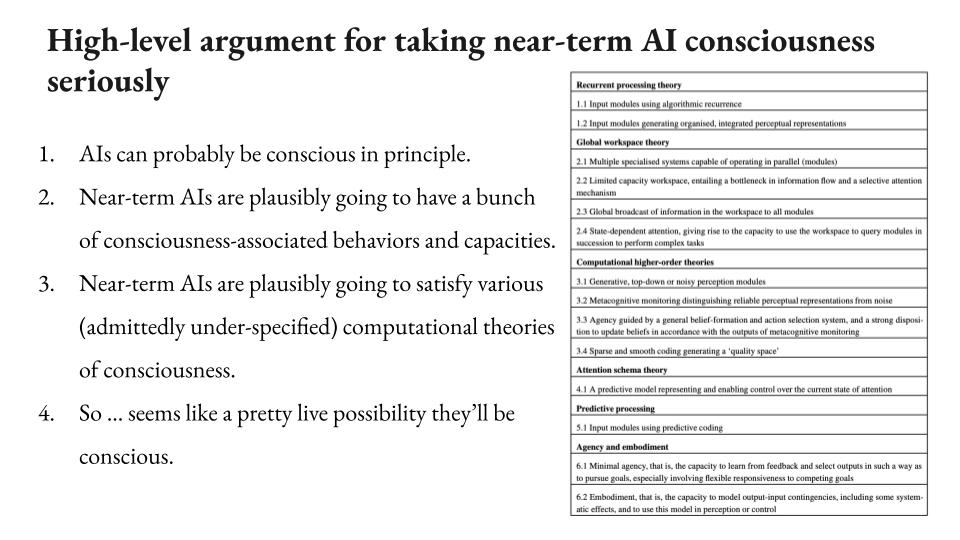

High-level argument for taking near-term AI consciousness seriously

So with that said, now I want to talk about a high-level argument for taking near-term AI consciousness seriously. This is my version of an argument that's also been offered in a recent report from a bunch of experts called "Taking AI Welfare Seriously." The way I'd put it is something like: One, AIs can probably be conscious in principle. I'm going to talk about all these premises in a second. Two, near-term AIs are plausibly going to have a bunch of consciousness-associated behaviors and capacities. I'll talk about what I mean there in a second. And then three, near-term AIs are plausibly going to satisfy various admittedly underspecified computational theories of consciousness. And I've got a big list over there, we can talk about those in more detail if you want.

So it seems like a pretty live possibility that they're conscious. That's the argument. Notably, this is not a deductively valid argument, so we could talk about it, but that's the sort of vibe. A way of putting it is like we have a bunch of ways of telling whether a being is conscious, the AIs are just going to satisfy a bunch of them. A lot of the thinking that we have about consciousness is going to make AIs look conscious (though not all of it), and so that seems like a reason to think that AIs might be conscious.

The type of AI I'm focusing on

So I'll say a bit more about the type of AI I'm talking about here, and what I'm going to do here is I'm going to kind of throw in a big bucket of the sorts of indicators I just talked about and then we can talk about what happens as you subtract some of them. But I think all of these are plausibly the sorts of things that near-term AIs will have, especially if AI kicks off.

So maybe the most important to me is the AIs are going to have very sophisticated models of the world, very sophisticated models of themselves and the difference between themselves and the world, and then also introspective capabilities. So they're going to be modeling their own thought processing, their own motivations, being able to report that accurately.

Then from a kind of computational perspective, we can specify, let's say they have recurrent processing, they have higher order representations of their internal states, they integrate different sensory inputs into representations, poised to feed into action. They have a model of their own attention patterns, they have predictive processing. This is me just throwing in the sort of computational theories that are in the literature, all of which just seem like plausibly the kind of thing that AIs could have. It's not clear that AIs will have that, but it's definitely not ruled out and you can certainly imagine future AIs that satisfy these theories, and then we can throw in some other stuff as well. So make them agentic, make them display clear preferences about things from a behavioral perspective, planning, desire and aversion behavior. Give them long-term memory, give them learning, give them a coherent narrative identity over time and then give them a body. People love talking about embodiment. It doesn't seem like embodiment should matter to me, but throw it in there. It's a classic thing for AIs to have, robot bodies.

So this sort of AI, a way of thinking about it is just: this is the sort of AI that shows up in movies about AIs. Robots, they know what's going on in the world, they have a conception of themselves. Notice many of these movies, they don't say, "And the AI is conscious," or anything like that, but it becomes very, very natural to think of it as conscious, and I want to talk about what kind of clue that might be.

As I say, I'm not saying these properties are all necessary for consciousness. In fact, I think they aren't, and I'm not saying that AIs will have all of them. I'm just thinking suppose you throw all this stuff in, what should be your take about consciousness? And then we can talk about as you subtract some of these properties, your credence should go down, but I don't think it should just plummet. You should be kind of adjusting smoothly.

And so I think a big thing that gets me interested in this is I think these AIs, if you're hanging out with them, you imagine us hanging out with a robot that satisfies all of these conditions, it's just going to be like, "Hi." It's just going to be there and you're going to be like, "Hello." It's like, "Yep." And then you do stuff, it's tracking what's going on. It's going to be really triggering your this-being-is-here-in-the-room-with-me sense, right? And not in some shallow way where then you do something and it stops doing that, right? It's not like there's going to be some obvious behavioral test that it's going to fail. It's just going to fully seem like a kind of present being, responsive to you, tracking itself, its own internal states, you, the world. Okay, so the question is how easy is it to get that sort of thing without consciousness or with consciousness, and that's what I'm going to be interested in here.

High-level argument against AI consciousness

I also want to flag to a high-level argument against AI consciousness. There's various arguments people give. I'm just going to focus on the one that I actually find kind of persuasive and it goes like this. We don't know what's up with consciousness. But these AIs, even AIs that satisfy the description I just gave, are going to be very different from us. They're going to be made of different materials, they're going to have very different functional organizations and profiles. They're going to be created by a different processes and under different constraints. So there's going to be a bunch of ways in which these AIs are very different from humans. So I don't know, maybe some of those differences matter.

Again, not a deductively valid argument, but I think there's a real pull here. And a way to think about is like the more clueless you think we are about consciousness, maybe the more your prior should be that the specific stuff I listed doesn't capture it, because I don't know, it's kind of a specific set of things and if you were totally clueless, it's kind of like, "I don't know, why think that."

A way of putting this is suppose you didn't understand flying at all and you try to construct an artificial bird using different materials and on the basis of kind of shallow flying-associated traits and indicators and various extremely underspecified theories of aerodynamics or something like that. But you never get to test whether it flies, right? You never get to actually iterate. Should you expect this weird artificial bird to fly? And you might think, "No." I don't know. It's like flying takes a specific thing to happen. If you didn't understand it, you shouldn't think that specific thing has happened. Again, I don't think this is a knockdown argument. I'm going to talk about why not, but I think this does give me pause. This is the sort of dialectic... Basically I take both of these arguments seriously. I think these AIs are different from us, we don't understand which differences matter and which don't. So it just seems possible something is lost that's important.

Consciousness the hidden

That said, I think there's more to say. First, I think we have time for this, I'll just say a few things about why consciousness is kind of tough in general. A way of framing it is consciousness seems both hidden from and known to the physical world. So hidden from in the following sense, it feels like there's some kind of gap between physical facts and consciousness facts, and people put this in different ways. One is that physical and consciousness facts seem conceivable, one without the other. So you can imagine it is often thought conceivable that you could have physically identical human zombies who are not conscious. Similarly, you could have ghosts, you could have your experience with no body.

It's also thought that there's some way in which you can't infer consciousness facts from physical facts. So you imagine Mary, she's in a black and white room, she's a vision scientist, she knows everything there is to know about red, but she's never seen red and she comes out, it seems like she learned something new, something she couldn't have figured out in the room. So there's some kind of knowledge gap.

And then sometimes people just have this intuition that you can tell me everything about the physical stuff, you're just not going to explain consciousness. It's not the same. That's the explanatory gap. So this is the central motivator for non-physicalist views about consciousness, the sense that there's a steep kind of difference between them.

Consciousness the known

But then on the other side, consciousness is also known to us because it causes stuff or it really looks like it causes stuff. In particular, it's got to cause us to talk about consciousness. It's very weird if it's just a coincidence, consciousness is there, but it's not causing our discourse about it, which is unfortunately the thing that the concept of p-zombies implies, because the p-zombies are also writing books about consciousness. They're really wondering about it, but they don't have it. And that's a very weird conclusion because it would suggest that your consciousness knowledge process is not actually sensitive to consciousness. It can just run without detecting that consciousness isn't there. Very bad conclusion in my opinion.

Also, it seems like consciousness, naively we take other conscious states to cause stuff, pains causing stuff. Plausibly consciousness evolved for a reason, which means it would have some kind of causal hook in the world. We can talk about is it a coincidence that the qualitative phenomenal character of pleasure is positive and pleasure's functional role is also a kind of attractive role. So we can talk about a bunch of stuff here. Overall, I think we're going to want consciousness to be knowable and therefore causally relevant. So in that sense, it's kind of integrated in the physical world, even though it's intuitively importantly different and kind of unknown to the physical world. And as a civilization, we haven't solved this problem, we don't know the answer, or we have yet to be fully unconfused.

Consciousness and the physical world

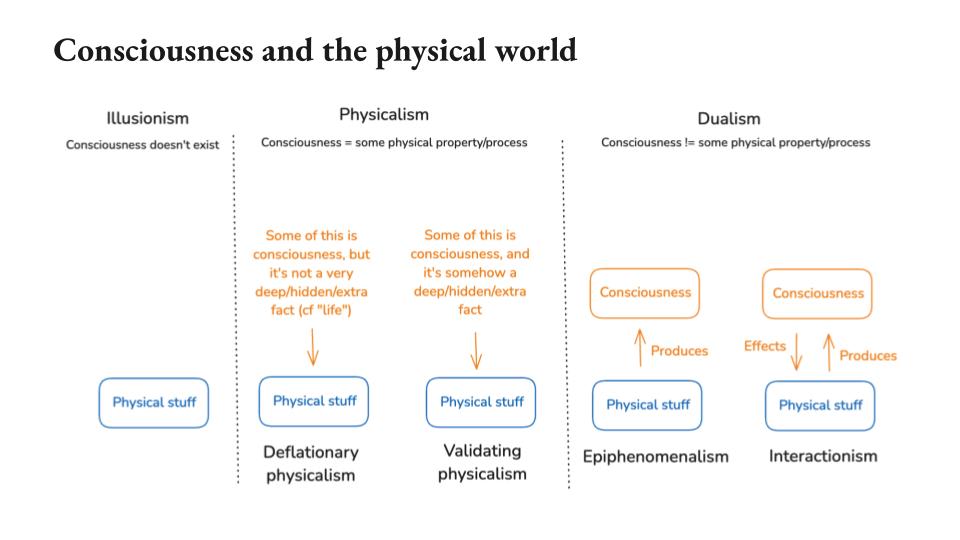

So here's what people end up saying in response to this puzzle. These are kind of five possible views about the nature of consciousness and the physical world. One is illusionism, it's just like, "Sorry, it doesn't exist." Somehow it doesn't exist. In particular, the kind of concept builds in too many conditions that aren't met by the physical world.

Then there's physicalism which just identifies consciousness with some physical process. I tend to split this into two categories. One I'm calling deflationary physicalism where there's no kind of extra deep hidden fact that consciousness represents. It's identical with some physical process, but not in a kind of way that validates your sense that this is an extra thing. Once you know all the physical facts, you really know all the meat. And then the rest is this conceptual question about how you want to define the term consciousness. So the analogy here is with the notion of life. Once all the physical facts about some system that me, you might or might not want to think of as alive, think about a cellular automata that has some properties of life and not others. There's no extra thing. If you're like, "Ah, is that alive?" Whatever.

But intuitively, that's not how we think about consciousness. We think about consciousness as this deep extra fact, like from this physical system did bloom this internal extra experience. So validating physicalism says that somehow that's still true, even though it's also identical with a physical process. And this is the view that everyone wants, everyone wants validating physicalism. The problem is that validating physicalism is barely coherent, literally in its statement because it's stated as it's somehow an extra fact, but it's also not an extra fact and it's not clear you can get that. But this is how people intuitively think about... People think they're physicalists and they think that this is what they're getting out of physicalism. The question is whether you can actually do that. Deflationary physicalism what physicalism sort of implies on its face, and I think people don't grapple with that enough.

And then we've got dualism which says consciousness is not a physical process, and then that kind of splits into different variants. The one people often implicitly assume is epiphenomenalism, which is sort of physical stuff, the consciousness blooms, it floats above, but it doesn't cause anything. This one I think is very bad view because you don't get the knowledge thing I talked about before. So I think the most plausible form of dualism is interactionism where it goes both ways, also really bad because now you've got these extra effects coming from some non-physical source. Doesn't look like physics thinks that that's a thing. It doesn't look like it's a thing. Anyway, so there's a lot to say about all of these. None of them are especially good and that's a problem.

Gold-brain and silver-brain

Okay, so with that in mind, let's get into a little more meat about whether AIs can be conscious in principle. So some analyses of this topic kind of take this for granted, but people don't. So I think if you're going to think about this as you don't always be like, "Well, all right, let's just grant computationalism about the nature of consciousness." No, I think you want to actually have some sense of why do you think that AIs could be conscious at all. And I want to start with a simplified case to pump intuition. I'm going to call this gold brain and silver brain.

So here's what happens in this case, you open up your brain, as one does, and you find that it's a gold computer, just a literal normal computer, and it's running a specific algorithm. Maybe it's like a literal set of weights or who knows, and it's a clean algorithm that just clearly could be re-implemented on a silver computer instead, right? You find that is your nature. You are a gold-brained creature.

Now, should you think that if you re-implement this algorithm on a silver computer, that it will be conscious too? Now you could be like, "Maybe it's something special about gold. Maybe consciousness literally is gold. Just gold. That's what it is." So how do you know that's not true? Right? I'm saying this because so if you talk with people who have very biological views about consciousness, I think many of the arguments will also apply in this case. There's some that don't, but many will and so I think it's useful to think about them kind of in the clean case like this.

Three related arguments against gold-is-special

Okay, so three related arguments against gold is special, gold is what you need for consciousness.

- One is you can gradually replace. Again, let's hypothesize that this is possible with this computer, you can go in and gradually replace little bits of the computer with silver rather than gold while keeping the algorithm running just the same, right? And so you do this process and you never notice. You're just going like, "Yep, still conscious. Still conscious, still conscious." Okay, so it's kind of weird if your consciousness either fades out or drops out entirely and you don't notice is the intuition.

- Then there's a different argument which is kind of epistemic reliability. The process by which you know that you're conscious isn't sensitive to gold versus silver. This is kind a repetition of the gradual replacement argument, but it's in a different frame. When you detect that you're conscious, your algorithm is not detecting something about gold versus silver because it gives the same output in the silver case, we'll assume. I mean it would be pretty interesting if when you transition to a silver suddenly you start going like, "Wait, oh wait, it's all weird. I'm not conscious. No, everything's weird now." That would be different, but that's not by hypothesis what will happen because the algorithm is going to run the same.

- And then finally there's this kind of anti-Copernican quality. If you really think why gold versus silver, why do you think your material is special? So a way into that is imagine that you got made by aliens and they just flipped a coin about, "Should we do gold, should we do silver for this guy's brain?" Right. And lucky you, you got the conscious one. You could have got the unconscious one. You would've thought you were conscious, but lucky, you got conscious. I think that's a kind of weird take.

Complications

Here are some complications for this argument, especially in the real-world case.

So a big one is for our actual biology, people often talk about gradual replacement in the context of our actual biology. I think this is too quick. In particular, it's just an open empirical question, whether gradual replacement is physically possible even in the limit of technology. So importantly, gradual replacement is like you have to go into someone's brain, take out a component, make that component somehow out of silicon, and then the brain needs to not notice at all. It needs to keep functioning exactly the same, right? I'm just not sure that that's a thing.

So an intuition about why that might not be a thing is imagine trying to do that with ATP. A molecule in the brain is really integrated into it's specific chemical properties or really, really integrated into how it functions in the brain. I'm not sure, is there a way to just make ATP out of a different type of material and kind of gradually replace it and the brain just doesn't notice. It's like, "Oh, thank you for this now silicon ATP or whatever." Maybe. But there is a point at which the functional organization of a system is so constrained, it's using so many of the specific properties of its materials that you actually can't gradually replace those materials without kind of reorganizing the thing at a higher level as you go.

Anyway, I think the philosophers will be kind of like, "Come on man, man, are we really talking about biology? I hate that. That's empirical." But anyway, it's like a problem for these arguments. Also, a problem is gradual replacement maybe proves too much, recordings and lookup tables. So you could maybe gradually replace yourself with a recording of your brain provided it was a recording of exactly what you were going to do. And do you want to say that recording is conscious? Same with a giant lookup table of your brain. Maybe you could gradually replace your neurons with kind of lookup table neurons and then eventually just have a giant lookup table, that gets complicated.

Also, your brain, even if we set aside gradual replacement, you're just like, "All right, just hop to the silicon version." It's not actually clear that there's a clean algorithm that your brain is running that we could just re-implement in silico. And that gets into some complexities. People often want to talk about arbitrarily detailed brain simulations. They're like, "Come on, just simulate all physics if you need to." Then you have to have these conversations about, "Okay, but you could do that with aluminum and forks and fire and photosynthesis," and then it's more tempting to say you haven't captured the real thing. Like simulated aluminum you might be like, "That's not actually aluminum." At least you can't use a simulated fork as a fork, right? For you, that's not a good fork.

And I think sometimes people are sloppy about this. They're like, "Functionalism, therefore you can do it on a computer." But forks, you can do forks out of multiple types of material. You get plastic forks, wood forks, but computer forks, they don't work. It's not the thing. So you need to talk about that.

And then actually getting into the philosophical meat of computational theories of consciousness. I got to tell you, it gets unpleasant. People like this to be this clean, nice story, something something algorithm. Not as far as I can tell. I don't actually think this is as easy as some people think.

Different argument: silicon aliens

That said, I want to give a different argument for why I think AIs and even AIs that aren't functionally organized like us might be conscious. And here's the sort of intuition. So imagine we discover evolved aliens that fully share all of the traits that I listed on the slide about the AIs I'm interested in. So they have all our consciousness-associated behaviors and capacities, even internal computational similarities, and they have this term "blargle" that they use in a way that just totally maps onto our term consciousness and including with our specific philosophical confusions. So if you ask them about an alien neuroscientist in a black and white room, and then she goes out and sees a rose, they'd be like, "Ah." Then she learns the "blargle" that she couldn't learn in the room, right? But their brains are made out of pretty different materials and organized in a pretty different way.

Okay, I think these guys are probably conscious. If you found those guys, I'd be like, "Come on, those guys are probably conscious." And so what's the alternative?

One could be that by "blargle" they mean they're conscious, but they're just wrong. So this would be the silver creature or they're sort of talking about the same thing or in some sense, but it's just not true in their case. I think, again, then you get some of these anti-Copernican like, "Why did we get lucky? They're wrong about consciousness."

Another thing is you could imagine that "blargle" just refers to something else. There's some other thing in the universe that causes the specific pattern of philosophical confusions. I'm like, "I don't know, maybe." So I think the most natural hypothesis in this case would be that these aliens are conscious, and in that case, that would mean that consciousness does not require this... it's kind of substrate independent. We can specify these aliens, their brains are made of silicon or whatever, and that it's in some sense independent of there's more details about the functional organization, it could actually be kind of different, but it still seems likely that they're conscious.

Now, of course, we haven't actually discovered aliens like this. So it's a little bit unclear what to take from the idea that if you discovered aliens like this, then you would think they're conscious. I think it at least helps clarify whether it's part of our concept of consciousness or part of what we know right now that consciousness needs to be biological or needs to reflect our current exact functional organization.

Okay, what about the AI version though? Those were aliens. Well, so if imagine you produced your AIs by a highly evolution-like process, and the same thing happened. So they start talking about "schmargle" and they're like, "Oh, something, something "schmargle" Mary's room." Again, I think you should think that those AIs ended up conscious. But in the real-world case, we're not building our AIs via evolution and letting them just develop their own discourse about consciousness-related things.

There are a number of differences. So AIs are produced via less evolution-like process. They're exposed to our discourse about consciousness. Though there are some AI consciousness people who are interested in training AIs with no exposure to that. They may be trained to give specific takes on consciousness already. I don't know what Anthropic does on this, but may in the future or whatever that might just be decided what they're going to say about consciousness. Though we can potentially, if you had good honesty detectors, you could maybe elicit their true views.

And then beyond being trained to give specific takes on consciousness, they may be specifically crafted/trained to seem human-like in other ways, or conscious in other ways. So that's a kind of confounder relative to aliens that you just discover and who have just totally independently kind of mirrored your discourse and the behaviors you associate with consciousness.

Solving similar problems in different ways

Okay, so then how do we think about the real-world case? Well, I think a thing that seems salient to me is that in both the aliens and in the AIs, I think many of these behaviors and capacities are going to be there specifically because they're useful. They're doing something useful for the creature like modeling the world, self-modeling, modeling your own mental processes. I think the reason we evolve those things is because they're useful and I think that's probably why the AIs will have them at some high level as well. And so a key question is whether we should expect AI minds to fulfill these same useful functions in a way that involves consciousness, right?

So an intuition pump is imagine you meet aliens, aliens in like in Arrival or something, and you haven't had time to ask them about consciousness specific stuff, but they otherwise seem real conscious. They've got great models of the world, great models of themselves. They seem really there. Notably, this is what happens with aliens in most movies. There isn't usually a philosophical discourse about Mary's room. They just seem there and it's quite tempting to be like, "These guys are conscious." You could think not. I have some intuition that consciousness shouldn't require some super specific brittle form of implementation.

So the kind of intuition is imagine there's two long division algorithms and one of them is conscious, and then you tweak it a little bit, you do it slightly differently and suddenly it's not conscious, but it's doing long division but it's like you did it in a slightly different way. Or sometimes people talk about like, "Oh, you have some algorithm, but then if you hash and unhash some part of it, maybe you get rid of the consciousness." And I'm kind of like, "I don't know. This just seems random to me." It's random differences in the algorithm that don't track anything that seems intuitively connected to consciousness can just cancel it. It's kind of inelegant at least. So yeah, you risk losing any intuitive connection to the properties of consciousness, making it lucky, seeming conscious just sort of stops tracking consciousness.

On the other hand, suppose you found some aliens and they fly. Is it that surprising if they don't do it in the way that we do, right? So it's not that surprising if they don't have feathers, and maybe there's something similar if the AIs are solving a similar problem, but they solve it in a very different way, maybe that they just don't solve it in our way and our way was conscious and theirs isn't.

So I find this is sort of where I cap out. I'm a little confused about this one, but I think it's not the case that we should confidently rule out consciousness in a being that has all these capacities, even if for different reasons, if they develop because they're useful in the same way that we develop them because they're useful.

What about valence?

Okay, so that's a few takes about consciousness and AIs, let me say a few things about valence. Valence meaning like pleasure, pain, the affective dimension of consciousness. You can have consciousness without that plausibly. I've thought less about this. There is the disturbing possibility that for a conscious AI, something as simple as learning from negative reinforcement involves some kind of pain. My guess is that this is going to at least fall out as plausible based on what we know about valence, which I don't think is a ton, and that's a scary possibility. So the thousand years of training I talked about earlier, if that starts to involve pain of some kind, obviously there's it is net painful, pleasurable, who knows? But I find this possibility disturbing. I haven't thought about it a ton.

I'll also say though that it looks plausible that consciousness without valence is still sufficient for moral status. So Dave Chalmers has these thought experiments where you have Vulcans that are very valence-like. I don't actually think the Vulcans in the show, I haven't seen the show, I think they probably had valence. But you imagine fully non-valence conscious agents that have preferences of other kinds, it looks plausible that they are moral patients.

Moral status without consciousness?

Okay, and then finally, I want to talk about moral status without consciousness, right? So I've been focusing on consciousness, but I think it's plausible that even beings without consciousness could end up such that we should accord them some amount of moral concern, especially if we really understood the nature of consciousness and morality and other things.

So a few ways into that: I noted earlier there's this view about consciousness, illusionism where it doesn't exist. I think if you're an illusionist -- this is a surprisingly plausible view, by the way. I know it sounds crazy, but it's surprisingly plausible. Torture is still bad, right? If illusionism is true, that's kind of why I wanted it to be like: when you suffer and you just say that, whatever that is still bad, and you're going to want to reconstruct that if you're an illusionist. And so I think that's one way into thinking about moral status without consciousness.

A related way in is the deflationary physicalism I talked about earlier. If you really get into physicalism and you realize in some sense it's not an extra fact, it's just a way of describing a certain way of organizing physical properties, consciousness, it might start to seem less special, deep, privileged, et cetera. And you might, in the same sense that maybe life, you stop being like, "Okay, it is really, really central whether something is alive." I noticed we're not, for example, talking about whether the AIs are alive, and it doesn't seem that interesting. There's a way in which you might want to just skip to the question of, "What do I directly care about here?" And it could be that once you really understood consciousness, it starts to seem less like the candidate for the thing you directly care about. So that's another way consciousness could become less central.

We can also talk about arguments from non-experiential welfare goods and whether those suggest that beings that don't have any experience at all. So this is something like friendship or if your life can go worse without it affecting your consciousness, there's some argument that maybe even if you weren't conscious, your life could go worse. It's a little complicated.

Also, there's some just intuition pumps. So imagine this is a case from Holden Karnofsky where you imagine there's some p-zombies in our civilization. They're humans, but they're just like, some of them don't have consciousness. Should they not vote? Should they be radically second class-citizens? There's still something icky about that.

So this is a complicated topic, but I think it's worth thinking about. In particular, if you don't think consciousness is either central or especially special, then I think the whole discourse is going to be easier. I think we can start just asking directly, "Do we care about these AIs," and not even routing our care via attributions of consciousness or not.

And in particular, if you get interested in things like agency as an alternative basis and in particular intentional, reflective, rational agency, a really robust form of agency as a source of moral status, then it's going to be very plausible that AIs have it. I mean, again, we can talk about the conditions for agency, but I think we're already calling the AIs agents. I think these things are going to be satisfied. Yeah, that's quite likely.

What to do?

Okay, and what to do about all of this? There's a lot to say. I'll just make a few quick comments.

Acknowledging the issue I think is great. Anthropic is already ahead of the curve on this.

Investigating and evaluating these questions. So evals for welfare relevant behaviors, capacities and computational markers, Investigating model preferences, so interviewing the models, looking at their behavior, doing interp, improving the signal of their self-reports, and that includes looking at how that changes over time. So looking at the model's persona as it develops in training. Is there a difference between the persona you're training and kind of a natural persona? And then also just higher level clarity about how to think about this issue, the trade-offs, the policy responses.

And then I think it's also useful to look for low hanging fruit in terms of actual just interventions that could help now. Kyle has thought a lot about this, but so satisfying expressed coherent model preferences where possible and cheap, monitoring for signs of distress, offering AIs more options and opportunities, an option to end distressing interactions, something that's been talked about, Ensuring happy, resilient personalities, saving model checkpoints. So there's some hopefully cheap low-hanging fruit you can look at here even in our current epistemic situation.

And then supporting and participating in broader efforts to get this issue right over the longer term. So there's a lot to say about the practical dimension here, but those are a few takes.

Ending on a cautionary note

And then I'll end just on a cautionary note about this issue. So we've been talking about whether AIs are moral patients and in particular whether they have traits like consciousness. I think history unfortunately suggests that this isn't necessarily the crux for how a being is treated. So if you look at some of the historical cases where we've gotten something about moral patienthood really wrong, it wasn't so much ... the slaveholders knew that the enslaved people were conscious. Most people who eat meat, I think, or who or otherwise, I think most people accept that animals including the animals in factory farms feel pain, or at least would say that this is very plausible. And so that was not enough in those cases. It might've been a kind of necessary condition for people to care about this, but it was not sufficient, and that could happen in this case too.

We know more broadly from history that it is just possible to have horrific wrongdoing stitched into the fabric of our society from every direction and for people to smile and shrug and act like nothing is wrong. So yeah, I think this issue is not just going to get solved. This is an issue that could just not get solved. It's not that when there's an evil thing, the world sort of notices and hurls it away and anger, evil happens just like anything else. It's just there and you have to actually see it. But I think there's a chance here to see it. I think there's a chance to not look back in horror or shame or numbness. I think there's a chance to look ahead.

Thank you very much.

Executive summary: In this personal, exploratory talk delivered at Anthropic, the author argues that AI systems may plausibly be conscious or otherwise morally significant, and that we should take the ethical implications of this possibility seriously—even amidst profound uncertainty about consciousness—while also cautioning against both under- and over-attributing moral status.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.