Johannes Haushofer and Richard Nerland

Summary

Malengo is a charity that facilitates international educational migration in the pursuit of poverty alleviation. Its flagship program supports Ugandan high school graduates in applying for and completing a Bachelor’s degree in Germany. Four years into Malengo’s operations and two years following GiveWell’s initial cost-effectiveness analysis, we present early results from our ongoing Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT), and an updated estimate of our impact based on these results. Early RCT results suggest that program beneficiaries experience a USD 843 increase in monthly labor income already in their first year in the program, adjusted for purchasing power. They also report substantially improved psychological well-being. There is no evidence of negative economic or psychological spillovers on parents and siblings at home; in fact, parents also report a substantial increase in psychological well-being. Updated program metrics suggest higher retention rates than originally assumed, with only 2 students out of 250 having returned home so far. We use these results to provide an updated Back-of-the-Envelope Calculation (BOTEC) in the style of GiveWell. The program is 28 times more effective than cash transfers in a baseline scenario, and 3,732 times in an optimistic scenario.

Introduction

Malengo was founded with the goal of facilitating substantial, long-lasting reductions in extreme poverty. Recognizing the limitations of other prominent interventions, such as unconditional cash transfers, our thesis is that the combination of international migration and education can produce much larger and durable income gains for low-income individuals from low-income countries (LICs). Malengo uses Income Share Agreements, through which successful beneficiaries repay all costs incurred in supporting their international migration, including effective interest reflecting cost of capital. This theoretically enables extraordinarily high cost effectiveness, as the intervention may prove to be fully cost-neutral or even profitable, with every dollar of funding unlocking migration and subsequent repayments that can then be reinvested in future generations of beneficiaries. We also hope that demonstrating positive returns on financing targeted beneficiaries will allow us to access the $4 trillion dollar global student financing market, from which low-income individuals from LICs have largely been excluded.

Four years into the program, and about 2 years after GiveWell’s grant and first analysis of Malengo’s cost effectiveness, here is an update on what we believe our impact is. We use GiveWell’s approach to measuring impact, which is mainly based on increases in logarithmic income for the scholar and household receiving remittances, but also incorporates mortality effects.

We focus on Malengo’s flagship program: the Uganda–Germany University Program, which supports high school graduates from low-income households in Uganda to apply for and complete a Bachelor’s degree at a German university. This program is the subject of an ongoing RCT, conducted under the supervision of Professors Toman Barsbai (University of Bristol), Marcelo Perez Alvarez (University of Groningen), and Matthias Sutter (Max Planck Institute for Research, Bonn), as well as PhD students Merve Demirel (Stockholm University) and Philipp Moskopp (Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn).

Early RCT Results

An important set of updates to our impact estimates for this program arises from preliminary data from this RCT, collected from the first 3 cohorts (2021–2023 program entry), interviewed in 2024. The current sample consists of a total of 318 applicants, of which 157 are in the treatment group. (The final sample will contain at least 850 participants.) The average time in Germany at the time of interview was 1.3 years, and the survey rate was 81%. The analyses completed by the research team so far average across all students without accounting for time in the program; however, because the 2023 cohort consisted of many more students than the previous two cohorts (2023: 120 students; 2022: 30 students; 2021: 7 students), the results can be broadly interpreted as reflecting effects after one year in the program.

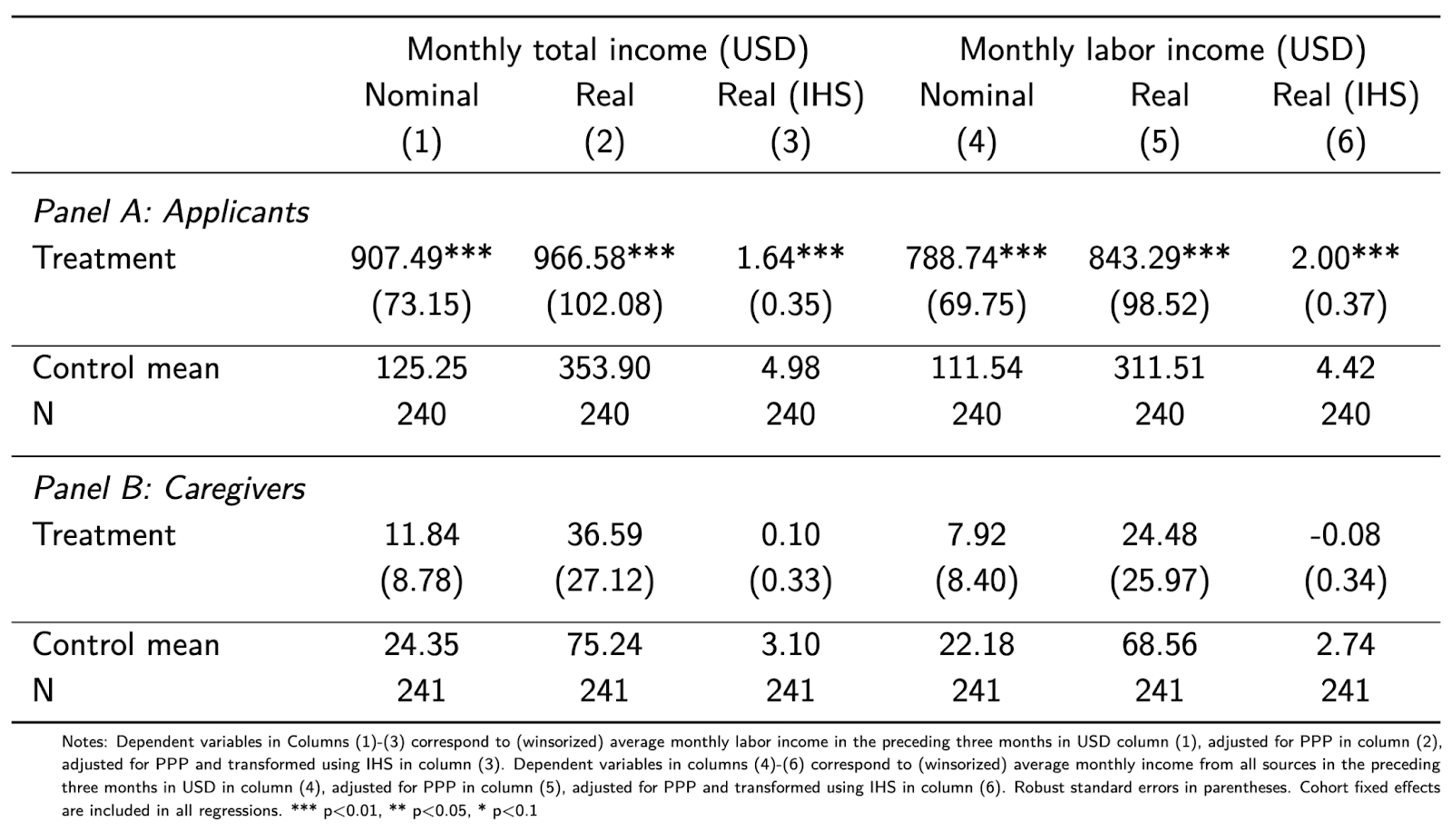

The research team reports substantial income increase amongst treatment students, with an average earnings increase of $907/month in nominal terms, and $967 in real terms, i.e. adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP; Table 1). Compared to the $354 control group mean, this represents a 273% increase in real terms. This increase includes Malengo’s stipends, which some students are still receiving at the time of the survey. Excluding transfers and focusing only on labor market income, the treatment effect is still $843 in real terms relative to a control group mean of $312, an increase of 271%.

Table 1: Impact on monthly income and earnings. The analysis presented here adjusts to USD PPP, reflecting purchasing power in high-income settings. In our GiveWell-style analysis below, all values are adjusted to Ugandan PPP levels, effectively converting outcomes to a common real-income baseline in Uganda. This methodological difference means that the RCT’s “real” figures appear larger when expressed in USD terms, while our GiveWell-style analysis expresses real impacts as they would be valued in Uganda. To maintain consistency with the original research, we retain the RCT team’s presentation here but preserve the original PPP-downward adjustment in our GiveWell-based modeling below.

Caregivers report their income increasing (Panel B of Table 1), and part of this increase is likely due to remittances. The results on remittances sent by the students themselves are still being analyzed. Based on preliminary figures, we assume that students send 8% of their income as remittances throughout their education and working life. This is likely a lower bound: once students earn a higher income in full-time work after graduation, they will be less cash-constrained and likely send higher amounts than at the moment.

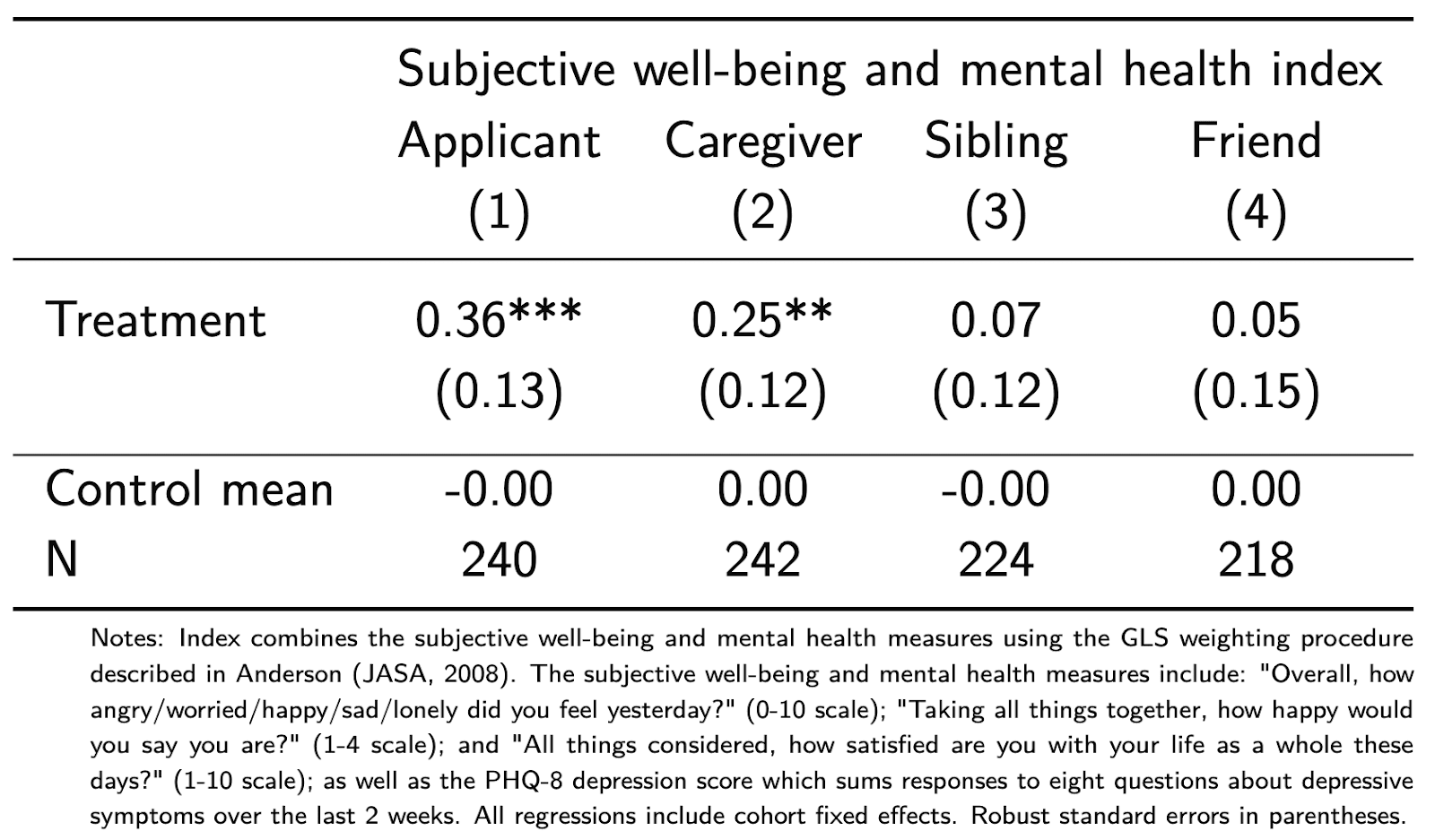

Psychological well-being of both students and parents is also positively affected, with a treatment effect of 0.36 standard deviations (SD) amongst students on an index of psychological wellbeing, and 0.25 SD amongst the parents (Table 2). The coefficients for siblings and friends back in Uganda are not statistically significant, but positive in sign. Importantly, we can rule out moderately sized negative psychological effects on those still in Uganda.

Table 2: Impact on psychological wellbeing. Units are standard deviations.

In addition, treated students report lower levels of discrimination and harassment (mostly driven by dramatically reduced sexual harassment amongst women), and siblings and friends report higher educational and income aspirations (not shown).

Ongoing Survey Results

In addition to the early RCT results reported above by the research team, Malengo itself conducts twice-yearly surveys amongst all students to assess academic progress and intentions to remain in the country. In our September 2025 survey (response rate 89%), 93% of our current students in Germany said that they “definitely” or “maybe” wanted to remain in Germany after graduation, either to get a job or pursue further education (Table 3).

| September 2025 (218 participants) | |

| Moderate to severe levels of anxiety/depression | 12% |

| B1 German or higher | 10% |

| Expected length of study (self-reported) | 4.3 years |

| Failed at least 1 exam ever | 50% |

| Average grade (among all passed subjects) | 2.7 |

| Would like to stay in Germany after BA | 93% |

| Has a job | 73% |

| Average monthly income of those with a job | €760 |

| Average savings | €2,366 |

| Average amount of remittances sent monthly | €152 |

Table 3: Results of September 2025 survey amongst Malengo students in Germany. Remittances sent are reported only for the cohorts which are no longer receiving Malengo stipends. The grading scale ranges from 1 (best) to 4 (pass); 5 (fail) is not reflected in the average grades.

Indeed, all ~250 students except for two are still in Germany and making progress towards their degrees. (We are still working with the two who left and will likely be able to bring them back in the future.) We have two notable updates related to completion likelihood and timeline.

First, program switching (from one university program to another) and pathway switching (from university to vocational training) has turned out to be feasible. On the one hand, this lengthens timelines (more on this below); on the other, it dramatically decreases the likelihood of not finishing any program at all, and allows students to pursue the education that best suits their talents and goals. We work with students on a case-by-case basis in making such switches, and on the order of 20–40 students have done so.

Second, the expected time to complete the program based on actual study progress is much longer than that based on self-reports; it is currently 7.7 years when averaging across all cohorts, based on a simple extrapolation of the number of credits accumulated to date. (Note this figure is not shown in the table above.) The approach based on actual achievement is more conservative; however, it should be considered in the context of three factors. First, it reflects to a significant degree the “slow start” that students get when they adjust to a new system, exacerbated by late arrivals due to visa delays. When we exclude the most recently arrived cohort, the average expected completion time is reduced to 5.9 years, and to 5.6 years when we exclude the two most recent cohorts. This suggests that students will catch up over time. Second and relatedly, in 2025, both Malengo and the German embassy in Uganda have been able to shift the timelines such that we expect the vast majority of students to be in Germany by the time classes start, in contrast to previous years. Finally, as we detail below, because we observe large income increases even in the first year in Germany, our impact model is now less dependent on graduation. Students realize substantial welfare gains as soon as they arrive in Germany, making timely graduation less critical for impact.

The survey also shows that a notable share of students (12%) report moderate or severe levels of anxiety or depression. This percentage is lower than that of 25% reported by Bolotnyy et al. (2022) for graduate students in US Economics departments. The discrepancy possibly reflects the fact that Malengo has invested significantly in psychological counseling for students, with the help of trained professionals.

Impact Model Updates

Based on these findings from both the RCT and the internal survey, we are in a position to update our impact model as detailed below. We use GiveWell’s 2023/2024 analysis of Malengo’s impact and the associated GiveWell Malengo BOTEC as the point of departure, and describe deviations from it. Our updates based on the results described above, and a direct comparison to GiveWell’s original analysis, can be found in a new BOTEC available here.

- Share of students graduating and remaining in Germany: 50% → 74%.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 4.8x cash.

We now have some additional evidence on the share of our students who are likely to graduate and remain in Germany long-term.

A first important datapoint that supports this view is that of the about 250 students Malengo sent to Germany, only two have had to move back to Uganda so far. Both those students will potentially return to Germany to join a vocational training program. This suggests that the dropout rate is likely to be very low. Students may take more time to graduate, but it is unlikely that they will not complete any program at all.

To obtain an updated quantitative estimate, we proceed as follows. In our September 2025 survey, 65% of students said that they definitely wished to remain in Germany; 28% reported that they “maybe” wanted to stay, and 7% said that they did not want to stay.

We rely on estimates from Özer et al. (2024) to transform staying intentions into actual outcomes. These authors find that intentions of migrants to remain in the host country are highly predictive of actually remaining: of those who intended to remain long-term, 89% were still in the country 5 years later. Even amongst those who did not intend to remain, the share was 29%.

We therefore assume that 89% of those who intend to remain will actually remain, and 29% of those who do not wish to stay. For the “maybes”, we use 81%, reflecting the figure from Özer for those who wanted to split their time. We then assume that an additional 10% of students do not remain to make the estimate even more conservative. Together, this results in a share of 74% of students remaining in Germany in the base case. This figure is relatively close to the 84% assumed in GiveWell’s “optimistic” scenario, but note that in our estimation it is now actually a rather conservative assumption.

We also model an optimistic scenario where 100% of those who intend to stay do so, 67% of those who do not intend to stay do so, and 90% of those who are unsure remain. Again we apply an additional 10% penalty. This results in an overall share of 85% staying. Malengo’s current track record — only two out of 250 students have left, all others are on track to complete a degree, and only 4% do not want to stay — resembles the optimistic case more than the base case.

We still have some uncertainty about the transition to employment after degree completion. We have hired a full-time staff member whose job is to facilitate this transition. They are heavily focusing on German language skills, which will both facilitate better study outcomes (mainly because it allows students to obtain part-time jobs that require less commuting, leaving more time for study) and make students more attractive for internships and to long-term employers. Program cost per person: $34,358 → $30,012.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 3.1x cash.

In GiveWell’s analysis, the cost of our program for a marginal student was $34,358. Our best estimate is that it is now $30,012. This estimate, in turn, is based on an “all-in” cost per student of $40,656, composed as shown in Table 5. Crucially, these figures represent an average cost derived by spreading substantial startup and infrastructure investments across a relatively small number of initial students. As the program scales, these fixed costs are spread over a much larger student base. Consequently, already now, the marginal cost of adding one additional student is significantly lower than the all-in average. We conservatively estimate that at current scale, a marginal student requires only 80% of the wrap-around service costs and 60% of overhead, with near-zero additional ISA setup costs. This places our current marginal cost at $30,012.Average Cost

Marginal Cost

Prep, travel, and landing cost $2,301

$2,301

Student living expenses and orientations $14,047

$14,047

Wrap-around services (e.g. mental health, legal) $6,018

$4,800

ISA servicing $3,540

$0

Indirect costs (staff, HR, finance) $14,750

$8,850

Total $40,656

$30,012

Table 4: Cost decomposition of Malengo University program.

Optimistic Scenario: Philanthropy as Risk Capital

In our optimistic scenario, we project a marginal cost of $18,233. This reduction is driven not only by operational efficiencies (further reducing the marginal cost of wrap-around services and indirect costs), but by a fundamental shift in our capital structure. We view current philanthropic donations as “risk capital” that proves the viability of the model. In the medium term, we expect this proof-of-concept to unlock debt financing from non-EA lenders (e.g., impact investors or facilities backed by Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). In this mature state, external lenders would finance the bulk of the ISA principal, while philanthropic funds would serve only as the risk buffer or "first-loss" guarantee.

An additional mechanism for reducing cost in the optimistic scenario is innovations in the ISA product itself. For example, in a revised ISA model, students might be able to pause or end the disbursements of their stipends once they have secured a part-time job, or make early repayments of money already received, thereby reducing their need for capital. We are currently exploring modifications to develop this model.- Average number of years between Malengo program and long-term benefits: 5 → 0 years.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 3.0x cash.

The reason for this change is that the part-time jobs students obtain in the first year already represent substantial income increases. Since students’ counterfactual income is $1,503, their student income of $13,310 already is three doublings vs. counterfactual income. Once they graduate, their income will increase by a factor of four, but much of the consumption gains happen before graduation. - Discount rate for future cohorts: 6.5% → 4%.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 3.0x cash.

In GiveWell’s model of Malengo’s impact, the future is discounted at 4% for all outcomes, with one exception: outcomes of all students who are financed through income share agreement repayments are discounted at 6.5%. We suspect this choice was made to capture “unknown unknowns” and execution risks. Instead of adjusting the discount rate, we account for these uncertainties directly by making conservative assumptions about student retention and graduation rate, salaries, program cost, etc., with a heuristic in mind of landing at the 25th percentile of the corresponding distribution. As a result, this uncertainty is already explicitly contained in the model inputs. To avoid penalizing the program twice for the same risks, we therefore apply the standard 4% discount rate for all outcomes. - Counterfactual income: $2,000/year → = $1,503/year.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 2.8x cash.

The new counterfactual income is based on survey reports from the RCT control group. Note these figures are in nominal terms; the model contains a PPP adjustment. - Working lifespan/duration of benefits, years: 40 → 59.4.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 2.8x cash.

This update is based on the most recent figures from Our World in Data for life expectancy in Germany, which is 81.4 years. We assume that the program benefits will persist until the end of life, which is plausible because Germany has a functioning pension system. - Household size in Germany: 3 → 3.5.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 2.6x cash.

We use 3.5 as the expected household size in Germany to reflect the fact that students on average in the future will likely live in couples and have 1.5 children (reflecting Germany’s low birth rate of around 1.4 children per woman, increased slightly to reflect the fact that the rate in Uganda is 4.5). - Repayment Compliance Rate: 90% → 98%.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 2.6x cash.

This rate applies to those who finish their degree and find a job in Germany; it therefore doesn’t concern repayments in other countries (e.g. for those who return to Uganda). This rate is based on the modeling of our partner organization Chancen eG, which assumes 2% defaults when estimating repayment compliance. We think this figure plausibly applies to Malengo students because:- Students are contractually obligated to repay. Our ISA contracts are fully enforceable in Germany. Students are obligated to keep Malengo updated about address changes and to provide income information and tax returns. They face (enforceable) financial penalties for failure to comply.

- Repayments are automatic: students are contractually obligated to provide Malengo with SEPA mandates so that we can automatically debit their bank accounts.

- Anecdotally, students are grateful to Malengo and motivated to repay. In our view this is the most important motivating factor.

- Remittances sent: $1,000 → $690.

Changes GiveWell’s estimate from 2.5x cash to 2.3x cash.

Based on Malengo’s RCT data. Note that this is a very conservative adjustment because it reflects remittances while students are still studying and earning low incomes. We expect that remittances will increase substantially once they graduate. - Income for those who migrate, net of remittances and repayment: $40,000 → $41,223.

No change to GiveWell’s estimate of 2.5x cash.

To update our earnings estimate for graduates in Germany, we proceeded as follows. We first obtained average salaries for a number of sectors in Germany — engineering, tech/IT, business, tax and law, natural sciences, agriculture, and humanities and others — both immediately after labor market entry, and 10 years thereafter. We then compute a weighted average based on the actual sector composition amongst Malengo students, and an annual growth rate based on the “immediate” and “10-year” figures.

To model students’ progression through university, we use Malengo’s RCT data to estimate monthly student incomes at $907.49 + $125.25 = $1032.74 (column 1 in Table 1 above). Beginning in the fifth year in Germany, students gradually enter the labor market; the cumulative transitions are: 20%, 40%, 55%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% over years 5 through 10 after program entry, respectively. Note that this is a conservative estimate relative to the expected average completion time of less than 6 years described above, because it implies that the median student enters the labor market in their seventh year in the program.

We then apply a 20% earnings penalty on the resulting income, to account for the fact that Malengo students may have a harder time placing in the labor market due to imperfect language skills and racism; some may leave the labor force temporarily for family reasons; and some may switch to lower-paying career paths. We then subtract from this income 8% of remittances; 14% of ISA repayments during the 10 repayment years following which students reach the EUR 27,000/year income threshold that triggers repayment.

Finally, we apply an annual discount rate of 4% to the resulting lifetime income stream and construct an annuity equivalent to the earnings curve so that we can ignore the non-linearity of graduation. (We also explored sensitivity to taxes and transfers and found it did not meaningfully change results.) - Life expectancy at birth in Uganda: 64.0 → 68.3.

No change to GiveWell’s estimate of 2.5x cash.

This update is based on the most recent figures from Our World in Data for life expectancy in Uganda. It leads to a reduction in the moral weight assigned by GiveWell on averting the death of a person that age, from 40 to 31, and therefore a reduction in the mortality benefits of the program from 5 to 4. - Average age of participant: 18 → 22.

No change to GiveWell’s estimate of 2.5x cash.

Based on Malengo’s RCT data.

Combining all these updates, we are now in a position to update our impact estimates:

Updated Baseline Impact Estimate: 28.4x cash

(Original GiveWell Estimate: 2.5x cash)

Updated Optimistic Impact Estimate: 3731.5x cash

(Original GiveWell Estimate: 17.3x cash

Relation to GiveWell’s updated estimates of GiveDirectly’s effectiveness

Note that these multiples are based on GiveWell’s estimate of the effectiveness of cash transfers as of early 2024, which was 0.0035 units of value per dollar. With GiveWell’s November 2024 updates to their estimates of GiveDirectly’s program, this value has increased to 0.09 units of value per dollar in Uganda. Importantly, however, Malengo’s impacts are almost entirely in cash/income increases. The impact multiple for Malengo therefore likely remains approximately the same. It could be lower if e.g. the general equilibrium effects of Malengo’s income gains accrue to richer individuals. This is unlikely for the remittances sent back to Uganda by the students, which reach their extremely poor families, many of whom live in equally poor communities. But it is likelier for the income gains of the students themselves, which will generate general equilibrium effects in Germany and thus benefit richer individuals. We have not modeled this distinction so far. For the sake of completeness, when we apply GiveWell’s new impact estimate for cash transfers, the baseline estimate of Malengo’s impact is 10.6x cash, and the optimistic estimate is 1391.0x cash.

Outlook

The research team is hoping to complete the intake for the RCT with this year's or next year's cohort. We still need funding for both the program costs and the research costs associated with the RCT; if you're in a position to support, please don't hesitate to reach out to Johannes Haushofer at johannes.haushofer@malengo.org. Through a new partnership with Neta, you can also invest in the success of Malengo's students through a DAF (minimum investment: $25,000). More detail about this option can be found here.

Thank you for reading!

|  |

| Johannes Haushofer, Founder & CEO | Richard Nerland, Investor & Board Member |

Hi Johannes and Richard,

It’s great to see the work of Malengo continuing! What a fascinating, ambitious project. Some questions.

Again, fascinating, and very cool work! I wish it to succeed.

First based on other income sharing agreement orgs, i think it's very likely they will recover close to all the money so I think that's a reasonable assumption.

A couple of comments/questions on this take here

"I think immigration may be one of the single greatest ways to increase human wellbeing, and (a hotter take) ultimately will be critical to maintaining the balance of power of democracies against autocracies"

Can you explain the pathway that immigration "may be one of the single greatest ways to increase human wellbeing". I can see how it has the potential to do good in many cases but "one of the single greatest" is a big call.

Also this..."immigration ultimately will be critical to maintaining the balance of power of democracies against autocracies". How would this work? my instinct would be in the other direction at the moment. I would say anti-immigration sentiment is one of the biggest drivers of the global trend towards autocracy around the world at the moment. The anti immigration sentiment has been a huge source of support for Trump, and in England/many European countries there's a similar dynamic. Do you think that immigrants are more likely to vote against autocratic leaders? That seems less and less the case, naturalized immigrant voters seem to be about 50/,50 on Trump last election, and even if we assume immigrant voters generally favor less authoritarian candidates, I really doubt that would overcome the harm the anti - immigration sentiment is bringing.

https://www.cato.org/blog/naturalized-immigrants-probably-voted-republican-2024

Germany is a decent test case too, where after bringing in 1 million immigrants,(which i support for the record) anti immigration sentiment has soared and has given the AFD a foothold.

My impression in Uganda is that there is increasing support for authoritarian regimes. many of my friends are huge fans of the West African Coups, and Africans might be the strongest Trump supporting countries in the world. just a few months ago 79 percent of Nigerians had at least some confidence in Trump, which is pretty mind-blowing

https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2025/06/11/confidence-in-trump/

I'm not an expert on this though and you might well have another mechanism for this statement.

Howdy Nick,

I was secretly hoping you'd show up given your past comments about brain drain.

Right, this comes from Sam and I's previous look into immigration. Based on this work, our working model is that immigrants adapt to the level of wellbeing (proxied by satisfaction) of the host country. If we take this seriously, then there's no known intervention that is more powerful than immigration. We can imagine this is plausible because immigration is a super intervention where you are getting tens to hundreds of potentially positive economic, health and psychological interventions altogether. Now, I also take this as a bit of a puzzle. Is it really the case that immigrating from India to the USA is ~2x better than moving from moderate to minimal depression symptoms?

One further thing is that this depends on preferring measures of satisfaction to happiness / mood. In some ongoing work it seems like the Kenya / Nigeria are about as happy as the UK even though they're less satisfied.

I'm curious what you think about this, since you've supposedly made the move down the ladder of life satisfaction by going from NZ to Uganda (but this is I assume a relatively smaller dip in terms of daily happiness).

I could have spoken more precisely here -- I meant that immigration is critical if we can do it right and not have it undermine our democracies (which is arguably what's happened in the USA).

This topic is outside of my happiness wheelhouse, and involves putting on my much smaller hat of geopolitics dilettante. But I buy the argument that to compete economically and deter militarily autocracies like China the west will need to be constituted by much larger countries, or have tighter alliances. Both prospects seem bleak at the moment. This is of course assuming we don't have an AI singularity and the world looks relatively normal by 20th century standards.

I'm not super familiar with the literature but I lean towards "yes", but I imagine this could depend quite a bit on the country of origin and the filter (e.g., Cuban Americans tend to be very anti-communist and Republican).

Thanks @JoelMcGuire for that wonderful response.

There's so much here to think about, which I think reflects the complexity of immigration as a topic, both as a debate about benefits/harms and the challenges measuring outcomes, especially if we throw wellbeing in there.

Immigration benefits/harms

I think Immigration is unusual as a GHD intervention, because it has the almost unique situation where there are many potential benefits and potential harms. Most global health charities like AMF/New Incentives/ just don't have this problem. An exception might be GiveDirectly where there were a lot of potential harms touted at first, but their research has put to bed a lot of the initial concerns about inflation/dependency/jealousy.

The main benefits of immigration are personal and measurable, whereas the potential harms are diffuse and hard to measure, although there have been attempts to model brain drain harms. I still think CEAs should at least discount a bit for these potential harms, but its tricky to be sure.

Potential Benefits (Some Included in CEAs)

- Improved Wellbeing of immigrant

- Remittances

- Migration opportunities for families (often not measured)

- Immigrants who return to the country with improved skills (often not measured)

Potential Harms (I've never seen included in CEAs)

- Loss of high impact country builders. The most talented, and motivated people who might go on to become politicians/innovators/business leaders and influence thousands of people are the ones leaving. These people aren't necessarily replaceable like regular workers. Malengo might be taking some of these, as their pool includesthat passed senior 6 well, which is the top 5%-10% of Uganda's talent

- Negative psychological/emotional effect on migration on the population remaining. "Japa" syndrome in Nigeria has been well documented, I'm scared of Uganda becoming like Nigeria, with everyone's eyes abroad, and people not investing in their own businesses/future in country but instead always thinking about/talking about/trying to leave. This would not make for a nice workplace!

- Fueling support for authoritarian regimes (hard to argue against at this point)

- Brain drain in general, which despite protestations does exist although it can be mitigated.

Scales and Surveys and Wellbeing

"Now, I also take this as a bit of a puzzle. Is it really the case that immigrating from India to the USA is ~2x better than moving from moderate to minimal depression symptoms?". Yeah this is either implausible or absurd. I wonder if you could find even one person who would consider this plausible. This incongruous issue should trigger a hard look into where the data problem is exactly. Different countries almost certainly have different scales, and that migrants will scale-adjust. This makes it hard/impossible to track wellbeing accurately when people move countries/. Also I wonder if you've considered that its more well off people who will generally be immigrating so they will on average be far happier than the average person before leaving. Its probably best to take the top quartile (or higher) of home country happiness statistics as baseline.

As I discussed in some of my first forays into the forum, going head to head with the mighty Michael, I have huge doubts about the veracity of before/after surveys in development. I straightforwardly buy point surveys of happiness/satisfaction surveys of the first order. But I don't put a lot of trust in before/after satisfaction surveys in where you do an intervention first, then survey satisfaction later. This concern cuts across including GiveDirectly, StrongMinds and here. I think Malengo is doing the right thing in doing before/after surveys as it is standard practise, I just don't buy it myself. I'm going to quote myself from 3 years ago

"Self reporting doesn't work because poor people here in Northern Uganda at least are primed to give low marks when reporting how they feel before an intervention, and then high marks afterwards - whether the intervention did anything or not. I have seen it personally here a number of times with fairly useless aid projects. I even asked people one time after a terrible farming training, whether they really thought the training helped as much as they had reported on the piece of paper. A couple of people laughed and said something like "No of course it didn't help, but if we give high grades we might get more and better help in future". this is an intelligent and rational response by recipients of aid, as of course good reports of an intervention increase their chances of getting more stuff in future, useful or not...

You also said "Also, we're comparing self-reports to other self-reports", which doesn't help the matter, because those who don't get help are likely to keep scoring the survey lowly because they feel like they didn't get help.

So Back to your question...

"Our working model is that immigrants adapt to the level of wellbeing (proxied by satisfaction) of the host country. If we take this seriously, then there's no known intervention that is more powerful than immigration.

I don't think that immigrants adapt to the satisfaction level of the host country (survey/scaling issues make this almost impossible to measure), although I do think there will be improvement. Then I think you also don't consider the potential harms which mitigate the power of immigration.

On my life...

"I'm curious what you think about this, since you've supposedly made the move down the ladder of life satisfaction by going from NZ to Uganda (but this is I assume a relatively smaller dip in terms of daily happiness). I'm afraid my case is too weird, I'm extremely happy and satisfied, but that won't help this discussion at all :D

On the political question...

"I could have spoken more precisely here -- I meant that immigration is critical if we can do it right and not have it undermine our democracies (which is arguably what's happened in the USA)." I agree with this in principle (And Richard's link on how to make immigration more appealing to host countries), but when it comes to considering interventions we need to observe the evidence of what is actually happening, not what we hope to happen. Right now (see my previous links) I think immigration isn't helping democracy, unfortunately...

On happiness vs. satisfaction

I must confess I'm a bit confused here, but its super interesting. I struggle to understand why these measures would be so different after looking at the questions. I think the jury is still out and I await the final authoritative report from HLI ;).

Thanks for this incredibly thoughtful comment and the BOTEC work! It is exciting to see someone digging into the implications for the WELLBY impact.

Here are my thoughts on your questions:

1. ISA Recovery & Cost per Person

You are right that the cost-effectiveness depends heavily on the recycling of funds. I built two related Monte Carlo simulations to assess the sensitivity of IRR, impact, and students educated to our input parameters. For the sake of brevity, I won't paste the full methodology here (it helps explain the logic behind the sheer number of variables), but I’ve attached a takeaway screenshot below. It shows how many students would be supported over the next 55 years with $1m in recycling investment.

The assumptions in our GiveWell sheet align with the p25 Scenario, which could be interpreted (539 student on an initial $1m investment, recycled) as a ~$2k cost per student.

https://malengo.org/impact_simulation/

I want to caveat that this has optimistic and pessimistic assumptions. There are some indivisibilities that could make expenses higher if the program runs at a smaller scale than a budget (explained below) of around $5m a year.

On the other hand, this represents completely unleveraged investment. With a stable underwriting model, Malengo (or similar lending with an educational migration approach) could eventually be lending against the contracts. A reasonable rule of thumb, if we are successful, would be achieving 5:1 leverage. In that scenario, $1m in the first-loss guarantee would unlock $5m in capital that would send at least 5x as many students, knocking the cost per student to $400. (Note: We might be able to swing something like 2:1 leverage at the moment, but it is a lot of work!)

In the true optimistic case, Malengo has infrastructure-like financing where donors wouldn't even need to donate to Malengo, they only offer a guarantee backed by assets in their DAF or Foundation or it is offered by a DFI and that unlocks bank loans that are serviced by the ISA obligations. In this scenario, philanthropy covers the fixed cost of building the "flywheel", while the scaling capital itself comes from credit markets.

I am hoping that our new CIO, Chad Sterbenz, will be able to post to the EA forum soon to do more justice to how this type of fund would work in practice with examples.

2. Cost Duration

To answer your clarification: Yes, the model accounts for 1-year stipend and then wrap-around support through the full duration of schooling. The "cost per person" is an all-in figure. It is derived from a conservative strategic plan: it represents the total dollars spent per student to sustain the entire organization for 20 years at a minimum viable scale (covering tuition, living cost gaps, and operational overhead), with a buffer in case a wind-down is required.

3. Disaggregated SWB/MH Measures

This is a great point about the difference between life satisfaction and affective happiness. I don't have that breakdown on hand, but I believe you are correct about the divergence. I will inquire with the research team about sharing those exact measures.

Regarding your BOTEC assumptions: Your spillover duration assumption (pegged to parents' lives) strikes me as reasonable, though perhaps conservative in scope. In practice, scholars send remittances to many family members, particularly to fund younger siblings' schooling. (We don't currently expect them to facilitate additional migration via their own funds). I actually incorporated a taper reflecting this into the impact simulation shared above after reading your comment. Thank you for that nudge!

Second, regarding the assumption that wellbeing benefits represent a flat line: I agree that is conservative. If the economic integration works as intended (see point 4), we should expect the convergence toward host-country wellbeing levels to be faster and stickier for these scholars than for the average migrant.

4. The Political Question & The OECD Graph

You anticipated the rejoinder perfectly. I’m with Alexander Kustov on this: migration has to be demonstrably beneficial to receiving countries. Migration will happen either through chaos or competence. Money can buy competence if the contract lets it.

The ISA is that contract: it pays for language, skills, and placement quality, and then pays itself back. We are betting that competence and successful integration are the best counter-arguments to populism.

As shown in your OECD chart, there is a massive gap in Germany between immigrants with foreign degrees and those with host-country degrees.

By ensuring our scholars get German degrees, we bypass the primary friction point. Our scholars face a lower "immigrant penalty" in the labor market sense; they (hopefully) perform almost identically to native-born graduates (We model 20% discount decaying as they integrate for 10 years of working). Malengo wants to demonstrate that deep economic integration can happen with sufficient resources.

Thank you for the response Richard!

I'm going to focus on the funds recycling since this seems like it may be the most important bit.

Since you're assuming $1mil recycled for a budget of $5mil does this imply that you will recycle 20% of costs? If so, that seems low given everything else you've said, so I assume I'm missing something.

The leverage point is really interesting. Do you have any current prospects for making the leverage work? I would guess you have to wait (how long?) to see if the default rate is sufficiently low for the ISA?

What has to be true for this to work out financially? Something like the real rate of return on $ / euro invested in students has to be equal or greater than the interest rate on the loan?

It'd be great to hear more about this!

When you mention $2k and $400 per student, could you explain how this differs from the $30k listed as the best guess in the spreadsheet. Sorry for all the questions, I just want to understand!

The mechanics of the fund are counter-intuitive compared to standard grant-making, so let me break down the math behind the $2k and $400 figures and how they relate to the $30k cost.

1. The Recycling vs. The Multiplier Effect

I think the confusion here stems from a coincidence of numbers in my previous comment. I mentioned a $5m budget and a $5m leverage target, but those are distinct concepts.

2. Financial Viability & Blended Capital

You asked: "Something like the real rate of return on $ / euro invested in students has to be equal or greater than the interest rate on the loan?"

Yes, exactly. In nominal terms, the Net Portfolio Yield (after defaults/expenses) must be greater than Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC).

In the p25 scenario, the Net Portfolio Yield is 3.8% (Listed under the IRR column).

This is too low to attract pure commercial capital (Even with data, European rates for this risk profile might be 4–7%). However, this is where Blended Finance comes in. We don't need 100% commercial capital; we can stack different tranches:

I have initiated talks with impact funds, DFIs, and banks to structure this. It is difficult to achieve, but within reach, so we hired a CIO. While lenders naturally want years of repayment data, there are creative ways to use philanthropic guarantees to de-risk them early on. We hope to share a more detailed write-up on the structuring of these capital stacks soon!

This is super helpful to have explained and makes more sense now.

So what is your best guess of the cost per student educated given Malengo's expected ability to recycle costs and leverage? What is the cost per person Malengo educates / facilitates the immigration of that you would put into my BOTEC?

At the risk of being pedantic, the answer depends heavily on your decision rule regarding uncertainty (relevant: Noah Haber's work on GiveWell's uncertainty problem).

I am comfortable recommending a rule that is internally valid with all our presented assumptions. Our analysis operates in the 25th percentile of outcomes; that implies a cost per student of $1,855. (This lines up with the ~95% cost coverage in your row 39, though that is a happy coincidence!)

However, if you choose to weight across the distribution, here is how the cost per student evolves based on recycling performance and leverage assumptions:

Note: These figures are derived from the distribution in the top comment: $1m / (num_students * leverage).

If you want my personal "best guess": I believe management will react to the data. If we are able to iterate for a decade, we will push toward p90. The team will find cost reductions using partners and tech, optimize contract specifications to ensure we achieve the target leverage, and refine the underwriting model to find the students most likely to succeed.

So, for your BOTEC, I would put $141 per student (implying ~99.5% effective cost coverage via recycling + leverage). But bear in mind, you are speaking to the person who already made that wager!

I appreciate the caveat and you sharing your best guess!

Can you explain Panel B in Table 1 to me?

It looks to me like the income of the Caregivers in the treatment group is lower than in the control group.

Hi Milli,

good question — these are coefficients on the treatment dummy, so they represent the *difference* between the treatment and control groups. So the average caregiver salaries in the treatment group are given by the sum of the control group mean and the coefficients on treatment.

Best

Johannes