I often focus on trying to improve my ability to estimate how much it would cost to avert a DALY or to save the life of a kid under 5 years old by donating to a particular charity. I am especially trying to find an upper limit to these amounts, so that I can very honestly, and with a lot of authority, tell a potential donor that if they donate to a particular charity, they will avert at least one DALY or save at least 1 child's life for the given cost. I want to find such an upper limit so that there can be somewhere around at least a 95% chance that it is correct.

I think a lot of people that might be interested in donating to highly cost-effective charities don't end up doing that, because they just don't trust those charities and the estimates for how cost-effective they are. And, I think trying to find better upper limit values for this kind of thing could help improve the argument for giving money to these kinds of highly cost-effective charities.

As part of this, I recently started trying to figure out how to factor in the costs from various effective altruism or global health organizations that aren't directly doing charity work or even directly giving money to the charities that are directly doing the work, but that do work that facilitates the work that those charities do. For example, the WHO seems to do a lot of work that makes it possible for lots of charities to do their work, so it seems likely that I should try to account for those costs for the WHO.

So far, the best method I have come up with for estimating these kinds of costs is to:

- Add up the money spent on overhead activities like this.

- Compare it to the total impacted charity money that is flowing through the charities and organizations that are being helped by those overhead activities.

- Figure out a good estimate of an upper limit on how much good all the impacted charity money together does in dollars per DALY.

- Multiply the dollars per DALY by the amount spent by the organization and divide by the amount flowing through the applicable charities being helped. This should give you a final number of dollars per DALY of overhead cost from these types of organizations (like the WHO).

For example, doing this calculation for the WHO:

- Start with the budget of the WHO for both sub-Saharan Africa ($496 million) and the HQ ($597 million) added together ($1,093 million).

- Find the total impacted money flowing through the impacted organizations. I'm estimating this to be $114 billion because that is about how much the world spends on health interventions in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Figure out an upper limit of cost per DALY for health interventions in sub-Saharan Africa. It seems like $150/DALY is a good estimate for this.

- Multiply dollars per DALY ($150/DALY) by amount spent by WHO ($1,093 million) and divide by amount flowing through impacted organizations ($114 billion). That comes out to $1.44 per DALY that is overhead costs from the WHO.

Thus far I'm thinking it might be good to account for these kinds of costs from the following organizations: WHO, GiveWell, Rethink Priorities, Giving What We Can, The Life You Can Save, The Centre for Effective Altruism, 80,000 Hours

So I'm wondering:

- Does anyone have any ideas on how I could improve this calculation?

- Or which organizations I should include?

- Or other kinds of costs that I should try to account for?

And also:

- Does anyone have any arguments for why this calculation is unnecessary?

- And why it is only necessary to include the costs of the charity itself?

- Or how estimates from organizations like GiveWell are already accounting for these types of costs somehow?

- Or any other feedback?

I think I understand your perspective, but I think there are two different ways of looking at any particular charity opportunity, and that is only one of them. I think each applies in different circumstances to different extents, and it can be difficult to tell how much each applies, depending on circumstances.

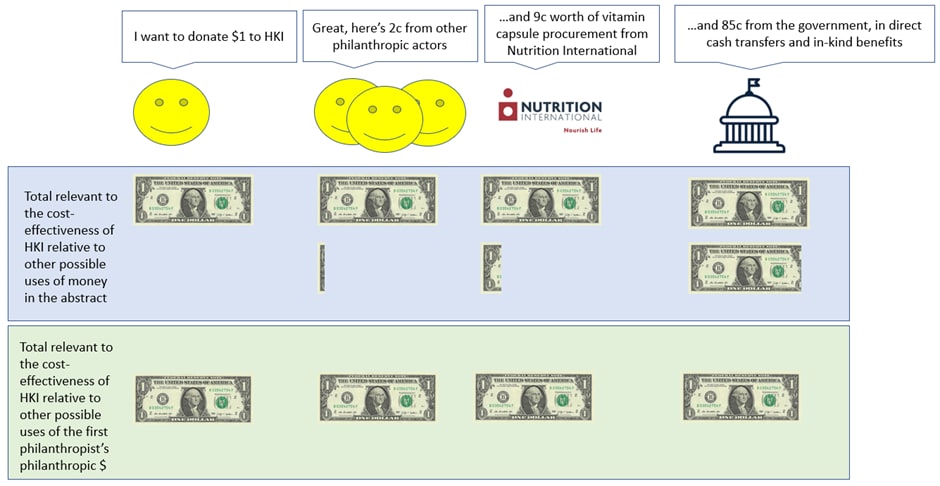

The first way of looking at it is the one that you described, where some other organization has already paid for its part of the health intervention, and would have paid for it regardless of if the donor donated any money. In that case, it might seem reasonable to me to mostly ignore the costs from the other organization, and only look at the cost paid by the donor when doing the CEA.

One example of where I think this would be applicable is when looking at a health intervention that has diminishing returns. For example, looking at AMF, probably the places where the LLINs will be most effective and least costly to distribute tend to receive them first. This could easily result in later LLINs being less cost-effective than earlier LLINs, so it might make sense to just look at what kind of impacting the donor is adding rather than looking at the total cost and impact of AMF.

The second way of looking at it is that the costs paid by the other organization were necessary for the health intervention, so we should account for those costs, although we would also need to somehow account for any other impacts from what the other organization spent. I think this way of looking at it is particularly valid if the money from the other organization will only be spent if the donor makes the donor's donation, but I don't think that's a requirement.

For example, on the AMF website, it says "100% of public donations buys long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs). An LLIN costs US$2.00." But there are actually many other necessary costs that need to be paid in order for LLINs to be effective, like the costs of distribution and the costs of figuring out where additional LLINs are needed. So, if we assumed that $2/LLIN was the only cost being paid, we would end up with incorrect cost-effectiveness numbers.

One thing that I think can help decide which perspective to use is the relative cost-effectiveness of the other organization's impact alone vs. the donor's donation alone. If the cost-effectiveness of the other organization's donations is a lot better than the one for the primary donor's donation, then I think it might be safe not to account for the costs of the other organization's donations. But, if not, I think it might make sense to account for the other organization's costs.

For example, let's say an organization spends $100 on a health intervention that saves one life. Then the donor comes along and pays another $10 to save a second life, but that donor can only do it because of the $100 that the organization already paid. In this case I think the more accurate cost-effectiveness for saving a life would be ($100 + $10) / 2 = $55, rather than just $10. However, if someone is just looking at which charity to donate to rather than trying to figure out realistically how many lives will be saved by a given donation, I could see the applicable number being $10/life. That's because I could see someone from the charity saying, "Hey, somebody else made this $100 donation, but didn't give us the other $10, even though it would make the intervention a lot more cost-effective, and it would be great if you could make up the difference." That seems like a good donation to make. But if someone asked, "How many lives do your donations tend to save?", I think the $55/life number would be more accurate.

In my case, I think the cost-effectiveness of Lafiya Nigeria is dramatically better than the cost-effectiveness of most global health interventions, even GiveWell's top charities, so I think accounting for the overhead costs from other organizations might make sense. Although, maybe only in the context of figuring out how far the money will actually go, not necessarily in the context of trying to figure out which charity to donate to.

Also, to some extent, my cost-effectiveness number for Lafiya Nigeria just seems too low to be possible, so I'm trying to figure out what might be wrong with it. Trying to account for costs from organizations like the WHO seems like a promising path for doing that.

Thanks for all the feedback on this. I think I've done a lot more useful thinking regarding this as a result.