In this post, I lay out some different ways of looking at what’s alive right now.

This seems worth knowing about to me, but also hard to grasp because of how huge the numbers are. A lot of what I’m doing in the post is trying to find ways to get my human brain to understand big numbers about how the world is.

I don’t have a considered view on which organisms are sentient or how much, or on how much different organisms matter morally compared to other organisms.

Biomass

I like this graphic a lot:

It’s from Our World in Data article on Biodiversity and Wildlife [I recommend following the link so you can zoom in on the graphic], which pulls from a 2018 paper by Bar-On, Phillips and Milo.

Some of the headlines that OWID pull out:

- Life on earth is dominated by plants – they make up 82% of global biomass.

- The animal kingdom makes up just 0.4% of global biomass.

- Humans account for just 0.01% of biomass. However, our livestock outweighs wild mammals and birds ten-fold.

The reason to look at life on earth in terms of biomass rather than individual organisms is an intuition that this makes it more comparable: otherwise the numbers get dominated by loads and loads of tiny things, and the bigger things (which most people care more about) barely show up.[1]

Numbers

I’m still kind of interested in the absolute numbers though. I think this is partly because my brain is better at conceptualising ‘individual organisms’ than ‘weight in tonnes of carbon’.

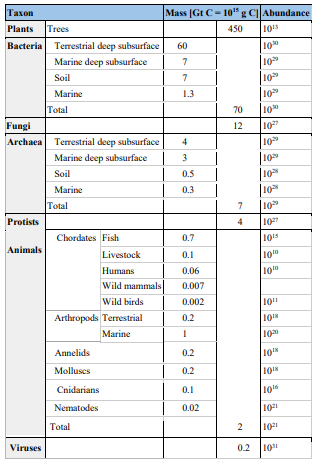

Bar-On, Phillips and Milo do give estimates for the absolute numbers (which they call ‘abundance’), to the nearest order of magnitude:[2]

| Taxon | Billion tonnes of carbon | Abundance | |||

| Total for subclass | Total for class | ||||

| Plants | Trees | 450 | 10^13 | ||

| Bacteria | Terrestrial deep subsurface | 60 | 10^30 | ||

| Marine deep subsurface | 7 | 10^29 | |||

| Soil | 7 | 10^29 | |||

| Marine | 1.3 | 10^29 | |||

| Total | 70 | 10^30 | |||

| Fungi | 12 | 10^27 | |||

| Archaea | Terrestrial deep subsurface | 4 | 10^29 | ||

| Marine deep subsurface | 3 | 10^29 | |||

| Soil | 0.5 | 10^28 | |||

| Marine | 0.3 | 10^28 | |||

| Total | 7 | 10^29 | |||

| Protists | 4 | 10^27 | |||

| Animals | Chordates | Fish | 0.7 | 10^15 | |

| Livestock | 0.1 | 10^10 | |||

| Humans | 0.06 | 10^10 | |||

| Wild mammals | 0.007 | - | |||

| Wild birds | 0.002 | 10^11 | |||

| Arthropods | Terrestrial | 0.2 | 10^18 | ||

| Marine | 1 | 10^20 | |||

| Annelids | 0.2 | 10^18 | |||

| Molluscs | 0.2 | 10^18 | |||

| Cnidarians | 0.1 | 10^16 | |||

| Nematodes | 0.02 | 10^21 | |||

| Total | 2 | 10^21 | |||

| Viruses | 0.2 | 10^31 | |||

(See also this post by Brian Tomasik for another set of estimates and much number crunching.)

I want to zoom in on the animals part of this table. First, for people who like me don’t intuit how big the difference between 10^10 and 10^18 is, here is the animals part of the same table with zeros:

| Chordates | Fish | 1,000,000,000,000,000 |

| Livestock | 10,000,000,000 | |

| Humans | 10,000,000,000 | |

| Wild mammals | - | |

| Wild birds | 100,000,000,000 | |

| Arthropods | Terrestrial | 100,000,000,000,000,000 |

| Marine | 10,000,000,000,000,000,000 | |

| Annelids | 100,000,000,000,000,000 | |

| Molluscs | 100,000,000,000,000,000 | |

| Cnidarians | 10,000,000,000,000,000 | |

| Nematodes | 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 | |

So for every one human, there’s something like 10 billion nematodes.

The estimates Bar-On, Phillips and Milo give are orders of magnitude (which makes sense given how big most of the numbers are). For some of the smaller numbers, we can get more precise estimates. Here’s a table I made with some more numbers I was interested and able to find:

| Order of magnitude from Bar-On, Phillips and Milo | Estimate | Year | ||

| Fish | 1 quadrillion (a million billions) | Farmed fish | 126.5 billion[3] | 2015 |

| Wild fish | 999,873.5 billion (999.9 trillion)[4] | - | ||

| Livestock | 10 billion | Poultry | 25.7 billion[5] | 2018 |

| Cows | 1.5 billion | 2018 | ||

| Sheep | 1.2 billion | 2014 | ||

| Goats | 1 billion | 2014 | ||

| Pigs | 1 billion | 2018 | ||

| Humans | 10 billion | - | 8 billion | 2022 |

| Wild mammals | - | - | 550 billion[6] | -[7] |

My brain can track these numbers better than the raw orders of magnitude. But even smaller numbers would be even easier for me to make sense of.

One way of getting smaller numbers is to think about how many organisms of different types there are for every individual human. So for each human alive today, there are:

- <1 cow, sheep, pig, and goat, respectively

- ~3 poultry in farms

- ~16 fish in farms

- ~70 wild mammals

- ~127,000 fish

What’s dying right now?

Another way of getting smaller numbers is to look at how many individual organisms die each year, or day, or minute. This is grim, and I feel a bit bad raising it, but it also seems important to have a sense of. Please skip this part if it’s too much for you.

The graph below shows an estimate for the number of deaths each minute, for humans and some kinds of farmed animals:

[Spreadsheet form here.]

That’s 2 people every second of every day.

Of the 116 humans who die each minute, roughly 2 have been deliberately killed by other humans. All of the fish, chickens, pigs, sheep and cows represented in the graph above are farmed animals who have been deliberately killed by humans.

Again, we can make these numbers smaller by asking how many deaths there are for each human death.

If I were to die in the next minute, more than 100 other humans would probably die with me. And in that minute, for each of those human deaths (including my own), the following animals would die:

- 5 cows

- 9 sheep

- 25 pigs

- 1,150 chickens

- 1,800 farmed fish

- ^

Brian Tomasik suggests that respiration might be an even better way of looking at life on earth, given that a lot of the biomass of trees is essentially dead. See here.

- ^

On p. 89 of their supplementary materials.

- ^

This is the midpoint of their range.

- ^

This is just the order of magnitude minus the estimate for farmed fish.

- ^

NB this is slightly lower than some estimates I've seen for just chicken populations. Not sure what's up with that.

- ^

This is the midpoint of Tomasik's range.

- ^

Post last updated in 2019; Tomasik is pulling from various sources and I don't think it makes much sense to give a year.

Thanks Elias, I think you're right.

Isaac, I've tried to make this clearer in the table in the post.

[Also by happy chance this process made me notice that I'd lost all of my footnotes in the process of transferring from google docs, which I've now fixed. Thanks both for indirectly causing me to notice this.]