Introduction

In this piece, I argue that mental illness may be one of the world’s most pressing problems.

Here is a summary of the key points:

- Not only does mental illness seem to cause as much, if not more, total worldwide unhappiness than global poverty, it also seems far more neglected.

- Effective mental health interventions exist currently. These have been improving over time and we can expect further improvements.

- I estimate the cost-effectiveness of a particular mental health organisation, StrongMinds, and claim it is (at least) four times more effective per dollar than GiveDirectly, a GiveWell recommended top charity. This assumes we understand cost-effectiveness in terms of happiness, as measured by self-reported life satisfaction.

- I explain why it’s unclear if StrongMinds is better than all the other GiveWell recommended life-improving charities (due to inconsistent evidence regarding negative spillovers from wealth increases) and life-saving charities (due to methodological issues about where on a 0-10 life satisfaction scale is the ‘neutral point’ equivalent to being dead).

- I make some initial suggestions for the highest-impact careers, as well as alternative donation opportunities. No thorough analysis has yet been done to compare these.

- While mental health has the most obvious appeal for those who believe we ought to be maximising the happiness of people alive today, I explain that belief isn’t necessary to conclude it is of the highest priority: someone could, in principle, value what happens to all possible sentient life and still reasonably decide this cause is where they’ll do the most good. I raise, but do not seek to resolve, the many crucial considerations here.

In order to get a sense of how important work on this area is, I examine (i) the scale, (ii) neglectedness, and (iii) tractability of the problem in turn. Ultimately, tractability - which I understand as cost-effectiveness - is what really matters and the preceding two sections should be seen as providing helpful background. I then set out why someone might - and might not - think this cause is their top priority and what they could do next if they decided it is.

Scale (how many suffer and by how much?)

Section summary: mental illness causes more suffering than poverty in developed countries, seems to cause roughly as much suffering worldwide as poverty does and, unlike poverty, is not shrinking.

The 2013 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) report estimated that depression affects approximately 350m people annually, while anxiety afflicts another 250 million.[1] By comparison, the report estimated that malaria affects 146 million people, while a 2015 World Bank report estimated 702 million people living on less than $1.25 a day.[2] While poverty affects many more people than mental health, the share of the world population living in absolute poverty is falling rapidly: there were 1.76 billion in absolute poverty in 1999, a drop of about 1 billion people.[3] By contrast, severe mental illnesses are on the rise.[4] As one example, in the UK the proportion of those reporting severe symptoms of common mental disorders has risen 34.7% between 1993 and 2014 (from 6.9% to 9.3% of the population).[5] It’s unlikely this is solely due to increased reporting: an American birth cohort analysis running from 1938 to 2010 found large increases in all psychopathologies after using standard methods to control for possible increases in reporting.[6]

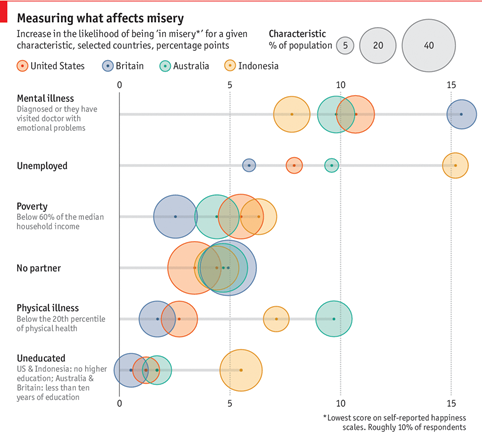

To properly assess scale we also need to know how much suffering each causes: if poverty makes people miserable but mental illnesses are only mildly bad, poverty will be larger in scale. In a recent analysis of self-reported happiness scores, the World Happiness Report evaluated how well poverty, lack of education, unemployment, being single, physical health (N.B. not just malaria) and mental health explain misery, where ‘misery’ here refers to those reporting the lowest happiness scores, roughly the bottom 10%.[7] Happiness is standardly measured by asking, “Overall how satisfied are you with your life these days?” measured on a scale of 1 to 10 (from ‘extremely dissatisfied’ to ‘extremely satisfied’).[8] For discussion of whether such measures of happiness are meaningful in general, see Dolan and White (2007) and Diener, Inglehart and Tay (2013) and for whether are cross-nationally comparable, see Veenhoven (2012).[9] The authors of the World Happiness Report found mental illness was the biggest cause of misery overall (i.e. it accounts for the largest proportion of those in the miserable category). This is represented in figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Mental illness increases the likelihood of being ‘in misery’ the most. Graphics from The Economist, underlying data from World Happiness Report 2017 (ch.5)

Three of the surveyed countries were developed (UK, USA, Australia) and one was not (Indonesia), but in each country emotional problems were the biggest cause of misery. Interestingly, mental illness was still the biggest cause of lost happiness if we look at the non-miserable part of the population too.[10] Of course, we may well expect poverty causes a larger amount of misery in countries even poorer than Indonesia - I’m not aware of an equivalent analysis of very poor countries - so there’s room to disagree about whether poverty or mental illness causes the most unhappiness worldwide.

For our purposes, it’s not essential to work out which of those two is bigger. The key point is that the worldwide scale of suffering caused by mental illness is huge, and at least of the same order of magnitude as poverty. It will almost inevitably increase, relative to poverty, over time. I expect this to be a surprise to many readers; it certainly was to me, as I had assumed poverty caused far more global suffering.[11]

Neglectedness (how many resources are going towards this problem?)

Section summary: Mental health is neglected, even relative to poverty and physical health.

One third of Lower and Middle Income (i.e. developing) Countries do not have a designated mental health budget,[12] and for those that do the average expenditure is 0.5% of their total health budget.[13] In such countries, the treatment gap for mental health (i.e. the number who don’t get treatment as a percentage of those who need it) is 76-85%.[14] A Centre for Global Development report describes mental illness as a “truly neglected area of global health policy”.[15]

Tractability (are there cost-effective solutions?)

Section summary: existing psychological treatments for mental illness are effective; more effective interventions seem to be on the horizon.

Even if mental health is a large-scale, neglected problem, we shouldn’t consider it a possible moral priority if there aren’t effective treatments. Fortunately, there are. Broadly, we can divide the treatments into three types. (Discussion of the cost-effectiveness of mental health treatments, relative to GiveWell top recommendations, occurs in the next section.)

First, there are psychological treatments. While many people’s mental image of this is still Freudian psychoanalysis (“lie down on the couch; tell me about your childhood”), such therapy has been shown to be ineffective and modern medicine has moved on. In fact, there are no randomised trials which have demonstrated psychoanalysis does better than the natural rate of recovery.[16] The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), as the first line treatment for all mental health disorders.[17] CBT involves teaching people how to understand their thoughts and emotions and process them differently. The UK’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme treats 560,000 patients a year, of whom 50% recover and two-thirds show worthwhile benefits.[18]

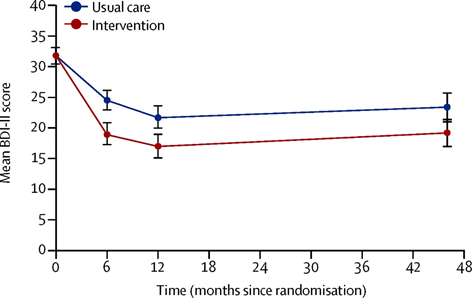

CBT is best understood as a family of therapies, rather than a single treatment: the CBT procedures for depression and, say, social phobia, share almost no overlap.[19] The latest forms of CBT are a substantial improvement on earlier methods. For example, 78% of patients with social anxiety recovered from cognitive treatments, compared with 38% from exposure therapy, which was the original (non-psychoanalytic) procedure used to treat it. [20] The effects of CBT can be long-lasting, too. A study on CBT recipients found the effects of treatment (compared to usual care with antidepressants), measured in standard mental health scores, were present 4 years later without obviously appearing to reduce over time, as shown in figure 2. [21] This can be explained by the fact that CBT teaches the patient a skill; so as long as they remember what they’ve learnt, the effect should continue.

Figure 2. The effect of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) remains for at least 4 years, as indicated by the lower mean scores for the treatment group on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), compared to the control group.

CBT is not the only effective psychological therapy: others include mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, interpersonal therapy, and counselling.[22]

Psychological treatments are conventionally delivered face-to-face, either one-on-one or in a group setting. A leading example of a charity in the developing world providing these types of intervention is StrongMinds, which offers interpersonal group therapy to women in Uganda.[23] Such treatments can also be effectively delivered electronically, either via computers or smartphones.[24] As this doesn’t require human interaction, it could potentially be very cheap and scalable.

Second, there are chemical treatments, the best known being antidepressants.[25] Despite controversy, evidence shows they are effective (more so for severe than mild or moderate depression), although they seem to function like painkillers, treating the symptoms without removing the underlying cause(s). This explains why cognitive treatments, unlike antidepressants, reduce the rates of relapse.[26]

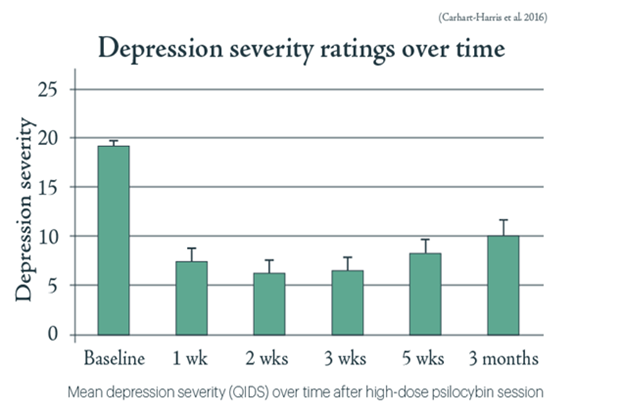

There are also some highly promising treatments for mental illnesses that rely on currently illegal recreational drugs. Ketamine may provide substantial short-term relief from depression.[27] MDMA (‘ecstasy’) has recently been labelled a ‘breakthrough drug’ by the FDA in the USA because of its remarkable effectiveness in treating post-traumatic stress disorder.[28] Perhaps most promising of all is the potential of psychedelics, such as LSD and psilocybin (the active ingredient in ‘magic mushrooms’) for treating mental illness. Carhart-Harris et al. (2016) gave a single dose of psilocybin to 12 people with moderate to severe treatment-resistant depression.[29] The subjects had been depressed for a mean average of 17.8 years. After psychedelic-assisted therapy, 67% were classed as non-depressed after 1 week and 42% as non-depressed after 3 months without any further treatment. This is displayed in figure 3.

Figure 3. Depression severity dropped substantially after psilocybin treatment and shows an effect 3 months later without further treatment.

Stage-2 trials started in September 2018 to test the effectiveness of psilocybin on a larger scale. In October 2018 the FDA granted the 'breakthrough therapy' designation for psilocybin therapy for Treatment-resistant Depression. If psychedelics turn out to be even partially as effective as they first appear, they could still become the most-effective treatment for depression.[30]

Third, there are direct, or electrical, treatments, such as deep brain stimulation (DBS)[31] and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).[32] I am uncertain of how effective these are compared to other treatments, but note that NICE do not recommend these as a first-line treatment. Possibly, further research will improve them or demonstrate their potential.

Of course, we shouldn’t only be thinking about treating people who are already suffering, but also about prevention. One promising (psychological) method of prevention this would be ‘positive education’: teaching resilience and life skills in schools. A series of trials in Bhutan, Peru and Mexico involving over 750,000 students found that positive education not only improved measures of child well-being, but also increased standardised academic test scores.[33]

Overall, there are a number of ways to tackle mental illness and it remains to be seen which will be the best.

Mental health vs global development: comparing charity cost-effectiveness

Section summary: a mental health charity, StrongMinds, looks more cost-effective at improving lives than one of GiveWell’s top charities, GiveDirectly. This assumes we understand cost-effectiveness in terms of happiness, as measured by self-reported life satisfaction. It’s unclear if StrongMinds is better than all GiveWell’s life-improving charities (due to gaps in evidence regarding the size of negative spillover effects) or GiveWell’s life-saving charities (due to methodological issues about where on a 0-10 life satisfaction is the ‘neutral point’ equivalent to being dead).

Even if there are mental health interventions that work, effective altruists shouldn’t donate to organisations that combat mental illness if they can find something even better. As the global development charities recommended by GiveWell are widely accepted as the most effective organisations to donate to at present, they are the natural point of comparison.

I claim that, on the present evidence, a mental health charity, StrongMinds, is at least four times more cost-effective than at least one of GiveWell’s life-improving charities, GiveDirectly, which provides unconditional cash transfers to poor Kenyan farmers. I am not able to say whether it is better than GiveWell’s other life-improving charities - which all, ultimately, aim to alleviate poverty - or GiveWell’s life-saving charities. I will compare StrongMinds first to the life-improving, then to the life-saving, GiveWell recommendations, setting out the key uncertainty in each case.

StrongMinds vs GiveWell's recommended life-improving charities

To evaluate StrongMinds and GiveDirectly, we need to convert their impact into a common unit. I’ll use self-reported life satisfaction scores, as mentioned earlier, to make this comparison. In effect, the question becomes: which charity is more cost-effective at increasing life satisfaction? A longer treatment of how and why life satisfaction scores should be used to measure happiness can be found here.

A study of GiveDirectly indicates cash transfers increase life satisfaction by about 0.3 life satisfaction points - hereafter ‘LSPs’ - on a 10 point scale.[34] To explain, this effect would be equivalent to increasing my life satisfaction from 6 to 6.3 out of 10. This was measured after 4.3 months on average, but let's assume this effect lasts a whole year. I assume it is the same for everyone in the recipient household, and there are 5 people per household on average. Hence the annual LSP impact is 0.3 (LS/person) x 1 (year) x 5 (persons) = 1.5 LSPs. The average cash transfer is $750, implying a cost-effectiveness of 2 LSPs/$1000.

However, this may well overstate the effectiveness of cash transfers. It accounts only for the life satisfaction increase of recipients. Research into GiveDirectly has suggested that their cash transfers, while making some people wealthier (and so more satisfied with life) have negative spillovers: it makes non-recipients less satisfied with their lives. As Haushofer, Reisinger and Shapiro (2015, p1) state:

"The decrease in life satisfaction induced by transfers to neighbors more than offsets the direct positive effect of transfers, and is largest for individuals who did not receive a direct transfer themselves."[35]

While this result may surprise the reader, as Clark (2017) notes ‘there is considerable evidence from a variety of sources to suggest that well-being is a function of relative income’.[36] In other words, your absolute level of wealth matters much less than whether you are richer or poorer than your peers. Hence the finding about GiveDirectly is consistent with the other research on happiness. Indeed, Clark et al. (2018), using developed country data, finds doubling one person’s income causes a reduction in life-satisfaction in that individual’s peer group that is nearly identical in size to the life satisfaction gain to the individual themself [37]. What is novel about the 2015 GiveDirectly result is that it finds this relative effect at such a low level of absolute wealth.

We might hope these negative spillovers would dissipate eventually and, over the long run, cash transfers would be effective in increasing life satisfaction. A 2018 study on the long-term (3 year) effects of GiveDirectly by Haushofer and Shapiro (2018, p. 22) finds recipients, compared to non-recipients in distant villages, have 40% more assets but that recipients do no better on a psychological well-being index.[38] Hence, the effect seems to be in the short-term.

Confusingly however, GiveWell claim a more recent ‘general equilbrium’ (GE) study of GiveDirectly, to which GiveWell have been given private access to a draft, shows there is:

"No evidence of across village spillover effects on household asset ownership or subjective well-being. They find a positive spillover effect on subjective well-being of ineligible households within treatment villages".[39]

I note this (more recent) finding is inconsistent both with the 2015 paper, and the more general finding of relative income noted by Clark (et al.) above. Given this inconsistency, and without access to the draft, I’m unclear how to update my views accordingly. Let’s return to this concern in a moment.

There isn’t research on StrongMinds which has directly measured its impact in terms of life satisfaction, so I estimate this using other available information, explained this endnote.[41] I infer that the treatment effect is an increase 0.8 LSPs per person (to 1 d.p.; modelled either as 0.2 LSPs per person per year for 4 years, or 0.2 LSP in the first year with a 75% annual retention thereafter). StrongMinds say their per-participant costs are $102 (StrongMinds Q1.2018 report). That suggests the impact is 8 LSPs/$1000 (to 1 d.p.).

The cost-effectiveness evaluation between StrongMinds and GiveDirectly is not sensitive to inclusion of the negative spillovers as, even if we assume GiveDirectly has no negative spillover effects, then StrongMinds would still seem to be around four times more cost-effective (2 vs 8 LSPs/$1,000). Note that, if we were take the view that its negative spillovers were just as big as its positive impacts, then GiveDirectly would not increase aggregate life satisfaction at all and anything with a positive impact would be more cost-effective.

In contrast, the analysis of whether StrongMinds is cost-effective than GiveWell’s other life-improving charities - namely SCI, Deworm the World, SightSavers and END - is sensitive to how strong we think the negative spillover effect of increasing wealth is. To see this, we must first recognise these other charities could have negative spillovers: they all eventually increase the wealth of their beneficiaries. While those organisations provide deworming interventions, the vast majority of the benefit of deworming, according to GiveWell, comes not from reducing the physical discomfort the worms cause, but from the fact dewormed children earn more in later life.[42] If it’s generally true that making some wealthier (and so more satisfied), reduces the satisfaction by others to at least extent, then this concern will apply there too. Second, note that, according to GiveWell, all these other charities are at least four times more cost-effective than GiveDirectly: Deworm the World is rated as 18.3 times better (the highest), and END 5.5 (the lowest). If StrongMinds is only 4 times more cost-effective on GiveDirectly then, assuming there are no negative spillovers, all these other charities would be better (assuming GiveWell’s analysis is otherwise correct). If, on the other hand, these charities have negative spillovers large enough to entirely cancel out their positive impacts, then StrongMinds will be better. Thus, the size of negative spillovers is highly important, which is why it is frustrating the evidence is inconsistent (at least, it is once we account for the latest, unpublished draft of GiveDirectly seen by GiveWell).

I am not able to offer a resolution to this issue here. What I think follows from this analysis is (a) more work is needed on understanding the size of negative spillover effects from wealth increases, (b) the possibility mental health intervention could be more cost-effective than the best poverty-alleviation interventions should be taken seriously and (c) given how little scrutiny mental health has received with effective altruism, efforts to find even more effective mental health interventions are valuable.

StrongMinds vs GiveWell's recommended life-saving charities

The other important comparison to make is between the life-improving mental health intervention, StrongMinds, and GiveWell’s recommended life-saving interventions, such as the Against Malaria Foundation (AMF). This is analysis is not very straightforward. First, there are different philosophical views about the badness of an individual’s death, as I note elsewhere.[43] Second, a thorough analysis would also need to take into account the ‘social value’ of lives, the value a given life has on everyone else. To assess this we’d need to account for the grief to friends and family saving a life prevents, as well as some complicated and potentially disturbing factors that are not usually considered, such as the meat eater problem[44] and whether or not the Earth is under- or overpopulated.[45]

I will put the complexities of the social value of lives to one side, and use the (simple) life comparative account of the badness of death, on which the value of saving a life is the total well-being the person would have had if they’d lived.

How cost-effective is AMF? According to GiveWell’s estimates, AMF saves a life (i.e. prevents a premature death) for around $3,500 [46]. Suppose that grants 60 counterfactual years of life. Let’s again use life satisfaction scores as our metric of well-being. Average life satisfaction in Kenya, where AMF operates, is 4.4 out of 10.[47] Now we run into a problem. Life satisfaction surveys don’t ask people to specify what point on the 0 to 10 scale they would consider equivalent to not being alive. 0 is labelled ‘extremely dissatisfied’ and 10 ‘extremely satisfied’. Intuitively, the mid-point in the scale, 5, would be the neutral point. Yet, if that’s true, then saving lives through AMF would, in fact, be bad: 4.4 (out of 10) is below the neutral point, so AMF are prolonging lives not worth living.

Let’s suppose instead the neutral point is 4. If this is so, saving the child is worth 0.4 life satisfaction points a year for 60 years, thus 24 LSPs (0.4 x 60). Given the $3,500 cost, we can calculate cost-effectiveness as 6.9 LSPs/$1,000. Earlier, I estimated StrongMinds’ cost-effectiveness was 8 LSPs/$1000.[48] If these estimates are correct, then StrongMinds is still more cost-effective, albeit only slightly, than AMF. Of course, we should be cautious about taking these estimates too literally.

The problem here is that these cost-effectiveness numbers are highly dependent on a (so far) arbitrary decision about where the neutral point goes. If someone instead assumes the neutral point were 3 - which, intuitively, seems too low - then AMF’s cost-effectiveness would leap to 24.4 LSPs/$1,000 and it would be more cost-effective than StrongMinds, at least on this simplified picture. I note this approach to comparing life-improving to life-comparing interventions (i.e. assessing how much additional life satisfaction is generated) is different GiveWell’s approach (i.e. asking their staff to judge how many years of doubled consumption are morally equivalent to saving a child’s life).

More work is therefore urgently needed to determine where the neutral point is. Two potential methods for doing this would be (1) asking people to state where they think this neutral point is; or (2) using mood reports and finding out at what score on the life satisfaction scale people report net neutral mood.

Why might you - and why might you not - prioritise this area?

Section summary: there are a large number of open-ended questions which need to be resolved before we can determine how we do the most good. This section sets out some of the crucial considerations, but does not attempt to answer them.

Ultimately, you should prioritise the problem that you think will allow you to do the most good with your spare resources (your time and money). Working out what will do the most good is obviously rather complicated. In this section I’ll set out some of the considerations that seem most relevant to deciding whether mental health could be your top priority. I do not consider this an exhaustive list.

Value: is happiness all that ultimately matters?

Earlier, I suggested a particular mental health charity might be more cost-effective at increasing happiness than at least one of the global development charities GiveWell recommend. Presumably, happiness, a positive balance of enjoyment over suffering, is one of the things that is intrinsically good, that is, good in itself. Some (including this author), believe it is the only intrinsic good.

If you believed there were other intrinsic goods, that would potentially change the priorities. Suppose you thought autonomy, equality and happiness were all valuable in themselves. As a result, you might, perhaps, think poverty is more important than mental health on the grounds poverty alleviation increases autonomy and equality whereas improving mental health does not.

However, such a conclusion might be a bit too quick. Even if you value things other than happiness, a mental health intervention might, from the point of view of your moral theory, still do the most good. You could believe targeting mental illness is just as autonomy-enhancing or equality-increasing as alleviating poverty, given how disabling it can be to be depressed, anxious, etc. Or, even if treating mental health does a poor job at promoting autonomy and equality, you might think that it does a good enough job of increasing happiness, something that you, presumably, value anyway, so as to compensate for its apparent lack of effect on other values.

Population ethics: do only some people matter morally, such as those currently alive, or does everyone who could ever live matter?

The (mathematically) simplest view in population ethics is totalism, which holds the best outcome is the one with the greatest sum total of well-being of everyone - past, present, and future. As a result, all possible people matter according to totalism.[49]

In contrast, many people intuitively hold a ‘person-affecting’ view of population ethics: while the well-being of those who do (or will) exist matters, there is no value in creating new lives. This is typically justified on the grounds that an outcome can be better or worse because and to the extent that it’s better or worse for persons, and existence can never be better or worse for a person than non-existence. Hence there’s no value in creating new lives, as being created is not good for anyone. Much of this is captured by Jan Narveson’s famous slogan “We are in favor of making people happy, but neutral about making happy people.” [50]

One particular person-affecting view is necessitarianism, which holds the only people who matter, when choosing between two outcomes, are those that are going to exist whatever we choose to do (i.e. exist necessarily). On this view, we still count the future people who will exist anyway. However, in practice, it’s unlikely there are many necessary, future people. The identities of who comes into existence depends, among other things, on whom the genetic parents of someone happen to be.[51] Given the nature of human reproduction, if your parents had had sex a moment earlier, or later, then someone else would almost certainly have been born instead. Plausibly, even small changes in the world are likely to change who gets conceived and thus alter the identities of future people. As a result, necessitarians will think our moral concerns are, in effect, restricted to those who presently exist.

As is probably obvious, whether you think a person-affecting view (e.g. necessitarianism) or what we can call an ‘impersonal’ view, one that counts all possible people (e.g. totalism), is correct may be a very important consideration in prioritising what to do (there are other views in population ethics, but it would be an unnecessary diversion to discuss those here). Some causes, such as reducing existential threats to humanity (e.g. from AI) or improving animal welfare (e.g. by reducing factory farming) primarily affect future people (technically: sentient life), rather than present people. By contrast, while alleviating the mental illness or reducing the poverty of those alive today will have some effect on future people, presumably their main impact is that they benefit the present generation. Thus, if you think an impersonal view is correct, you might think factory farming or reducing existential risks are simply a lot more important than mental health or poverty; if you think a person-affecting view is correct, mental health or poverty may be the priority instead.

Which is correct? Population ethics is a notoriously problematic area, where all of the views can be shown to have apparently implausible implications, and there is not space to get into this here.[52] (Psychologically autobiographical aside: I tend to think person-affecting views are the least-bad of the options).

Empirical and personal complications

Simply settling your moral views is not sufficient to tell you what to prioritise; there are a range of empirical considerations too.

For example, you could hold a person-affecting view but still conclude reducing existential risks is the top priority simply based on the risk they pose to the present generation.[53]

Or, you could hold an impersonal view - and therefore accept that it would be good, in theory, to make progress on animal welfare and shaping the far future - but nevertheless think, in practice, you can do more good by focusing on something in the near-term, such as mental health or global development instead. You might reach this conclusion if you held some of the following beliefs: (a) the expected value of the future will be negative, such that it would be good if sentient life dies out and so reducing existential risks would be bad; (b) there are especially good opportunities to do good in the present; (c) there is very little we can do to improve the far future; (d) we have a particular moral duty to help other existing humans compared to future humans or animals; or (e) (probably the most important of all) your skills, abilities and personal motivation mean you have particularly high aptitude to work on some nearer-cause area rather than another.

Finally, someone could decide that making currently existing humans lives happier (as opposed to, say, saving humanity), is how they’d do the most good, but not think mental health is the top priority. To state the obvious, mental illness is not the only source of unhappiness. If we could wave a magic wand and fully treat all mental health conditions, the world would not be at maximum happiness. Some possible contenders not otherwise mentioned in this document are:

- Pain. A recent Lancet Commission on the subject said, “lack of global access to pain relief and palliative care throughout the life cycle constitutes a global crisis, and action to close this divide between rich and poor is a moral, health, and ethical imperative”.[54]

- Loneliness (lacking friends) and ‘lovelessness’ (lacking a romantic partner). Given the amount of misery these seem to produce (e.g. see figure 1 ‘No partner’), finding a way to progress here could be high impact.

- ‘Ordinary human unhappiness’, which refers to mundane, everyday existence being less good than it could be. Even projects that attempt to cause seemingly trivial lifestyle changes, such as exercising more or encouraging people to take shorter commutes (commuting is shown, in time-use studies, to be one of the worst parts of the day), are potentially high impact if they have a small, but long-term, daily impact across many people.

How can you help?

Section summary: some initial charity and career recommendations are made. More work is needed here.

Let’s suppose you’ve decided that mental health is how you can do the most good with your time or money. What next?

Regarding charitable donations, StrongMinds seems to be the current low-risk favourite.

There are, however, other charities someone could consider, though none have yet been thoroughly evaluated against StrongMinds. These are, with brief explanations in brackets:

- Friendship Bench (a charity which provides problem solving therapy in Zimbabwe through lay health workers. They’ve had a RCT conducted on their intervention, which found an initial impact greater than my estimate for StrongMind’s; however, I don’t yet have costs so can’t make a cost-effectiveness calculation).

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) or The Psychedelic Society (both work to do research into, and increase access to, psychedelic treatments for mental illness).

- The International Positive Education (‘IPEN’; as the name suggests, the organisation aims to spread positive education in schools).

- Mental Health Research UK (currently funding PhDs in mental health research).

Regarding high impact careers, no systemic work has been done to evaluate what these might be. Intuitively, the following stand out as promising, but these are just some initial ideas:

- Cause prioritisation research - it’s hard to escape this conclusion, given how little work has been done. For those who are interested, I’ve highlighted some important questions in the following document: Human Welfare: A Research Agenda. I am in the process of forming an organisation to conduct such research. If you would like to participate, please contact me.

- Economics (or other social science) research into happiness, e.g. determining what the most effective government policies are.

- Research into new treatments for mental health, e.g. psychedelics, and/or advocacy for these treatments. Lee Sharkey and I have written about drug policy reform elsewhere.[55]

- Work in developing world mental health. Trying to improve organisations already in this area, possibly with a view to trying to start new, more effective ones.

- Entrepreneurship in mental health technology. There are some effective altruists working on projects in this area already, such as Mind Ease and UpLift.

- Politics or policy. Trying to change what governments do and their attitudes towards happiness.

Conclusion

Whilst mental health has so far not been considered one of the world’s most urgent problems among effective altruists, it seems, on further reflection, there is a strong case it should as high a priority as global health and development, a current EA top-cause. Given the variety of options for improving mental health, and the lack of prioritization research on the topic, it seems likely we’ll find even better ways to make progress on this problem in the near future. Establishing which cause allows one to do the most good is complicated. This document set out some of the crucial considerations relevant to deciding whether this should (or should not) be someone’s top priority; and suggested what you might do if you conclude working on improving mental health is how you will do the most good.

Endnotes

[0] I am very grateful to Max Dalton, Alex Lintz, Siebe Rozendaal, Justus Arnd, Andrew Fisher and Paul Davies for reading and offering comments on this draft.

[1] Theo Vos et al., “Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 301 Acute and Chronic Diseases and Injuries in 188 Countries, 1990–2013: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013,” The Lancet 386, no. 9995 (2015): 743–800, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. Depression and anxiety are the ‘common mental health disorders’; I’ve left out others such as schizophrenia, anorexia, bipolar disorder, etc.

[2] Vos et al.

[3] Ibid

[4] Brandon H. Hidaka, “Depression as a Disease of Modernity: Explanations for Increasing Prevalence,” Journal of Affective Disorders 140, no. 3 (November 2012): 205–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.036.

[5] NHS, “Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, England, 2014 - NHS Digital,” 2016, https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey-survey-of-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2014#key-facts.

[6] Jean M. Twenge et al., “Birth Cohort Increases in Psychopathology among Young Americans, 1938–2007: A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis of the MMPI,” Clinical Psychology Review 30, no. 2 (March 2010): 145–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.005.

[7] John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard, and Jeffrey Sachs, World Happiness Report 2017, chapter 5 (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2017), http://worldhappiness.report/ed/2017/.

[8] Ibid. Those interested in how life satisfaction (one of the components of what is sometimes called ‘subjective well-being’) is measured, and how reliable those measures are should see Ed Diener, Ronald Inglehart, and Louis Tay, “Theory and Validity of Life Satisfaction Scales,” Social Indicators Research 112, no. 3 (July 13, 2013): 497–527, OECD, Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being (OECD Publishing, 2013) and Paul Dolan and Mathew P. White, “How Can Measures of Subjective Well-Being Be Used to Inform Public Policy?,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 2, no. 1 (March 21, 2007): 71–85

[9] Dolan and White, “How Can Measures of Subjective Well-Being Be Used to Inform Public Policy?” Ed Diener, Ronald Inglehart, and Louis Tay, “Theory and Validity of Life Satisfaction Scales,” Social Indicators Research 112, no. 3 (July 13, 2013): 497–527, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0076-y. Ruut Veenhoven, “Cross-National Difference in Happiness: Cultural Measurement Bias or Effect of Culture?,” International Journal of Wellbeing 2, no. 4 (December 13, 2012), https://www.internationaljournalofwellbeing.org/index.php/ijow/article/view/98.

[10] Ibid. See also Sarah Fleche and Richard Layard, “Do More of Those in Misery Suffer from Poverty, Unemployment or Mental Illness?,” Kyklos 70, no. 1 (February 1, 2017): 27–41, https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12129.

[11] Another approach would be to use health metrics. This is less useful that using happiness scores for two reasons. First, that only allows us to compare health states, and we want to able to compare health states to poverty, which we can do with happiness scores. Second, health metrics (DALYs and QALYs) reflect how people who have mostly never experienced these illnesses imagine they would feel if they did so. A better alternative is to measure directly how people actually feel when they actually do experience the illness. When QALYs have been compared to happiness scores, it was found the public hugely underestimated by how much mental pain (compared with physical pain) would reduce their satisfaction with life, as discussed by Paul Dolan and Robert Metcalfe, “Valuing Health,” Medical Decision Making 32, no. 4 (July 2, 2012): 578–82, https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X11435173.

[12] Shekhar Saxena et al., “WHO’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems: Collecting Essential Information for Policy and Service Delivery,” Psychiatric Services 58, no. 6 (June 2007): 816–21, https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.816.

[13] WHO, Mental Health Atlas 2011 (World Health Organization, 2011).

[14] Victoria de Menil, “Missed Opportunities in Global Health: Identifying New Strategies to Improve Mental Health in LMICs,” 2015.

[15] Ibid

[16] A Roth and P Fonagy, What Works for Whom?: A Critical Review of Psychotherapy Research, 2nd ed. (Guilford Publications, 2005).

[17] Richard Layard and David M. (David Millar) Clark, Thrive : The Power of Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies, n.d.

[18] David M. Clark, “Realizing the Mass Public Benefit of Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies: The IAPT Program,” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 14, no. 1 (May 7, 2018): 159–83, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084833.

[19] Layard and Clark, Thrive : The Power of Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies. P143

[20] B Boecking, “Mechanism of Change in Cognitive Therapy for Social Phobia” (King’s College London, 2010).

[21] Nicola J Wiles et al., “Long-Term Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy as an Adjunct to Pharmacotherapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression in Primary Care: Follow-up of the CoBalT Randomised Controlled Trial,” The Lancet Psychiatry 3, no. 2 (February 1, 2016): 137–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00495-2.

[22] Layard and Clark, Thrive : The Power of Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies.

[23] For a longer discussion of mental health and StrongMinds, see John Halstead and James Snowden, “Cause Report - Mental Health,” n.d., https://founderspledge.com/research/Cause Report - Mental Health.pdf.

[24] KC Cukrowicz and TE Joiner, “Computer-Based Intervention for Anxious and Depressive Symptoms in a Non-Clinical Population,” Cognitive Therapy and Research, 2007, http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10608-006-9094-x. E Kaltenthaler et al., “Computerised Cognitive–behavioural Therapy for Depression: Systematic Review,” The British Journal Of, 2008, http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/193/3/181.short.

[25] Andrea Cipriani et al., “Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of 21 Antidepressant Drugs for the Acute Treatment of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis.,” Lancet (London, England) 391, no. 10128 (April 7, 2018): 1357–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. Irving Kirsch et al., “Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration,” ed. Phillipa Hay, PLoS Medicine 5, no. 2 (February 26, 2008): e45, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045.

[26] Keith S. Dobson et al., “Randomized Trial of Behavioral Activation, Cognitive Therapy, and Antidepressant Medication in the Prevention of Relapse and Recurrence in Major Depression.,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 76, no. 3 (June 2008): 468–77, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.468.

[27] Olivia F O’Leary, Timothy G Dinan, and John F Cryan, “Faster, Better, Stronger: Towards New Antidepressant Therapeutic Strategies,” European Journal of Pharmacology 753 (April 2015): 32–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.046. Marije aan het Rot et al., “Safety and Efficacy of Repeated-Dose Intravenous Ketamine for Treatment-Resistant Depression,” Biological Psychiatry 67, no. 2 (January 15, 2010): 139–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2009.08.038. Rebecca Brachman, Could a Drug Prevent Depression and PTSD? | TED Talk, 2016, https://www.ted.com/talks/rebecca_brachman_could_a_drug_prevent_depression_and_ptsd/transcript?language=en.

[28] MAPS, “FDA Grants Breakthrough Therapy Designation for MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for PTSD, Agrees on Special Protocol Assessment for Phase 3 Trials,” 2017, https://maps.org/news/media/6786-press-release-fda-grants-breakthrough-therapy-designation-for-mdma-assisted-psychotherapy-for-ptsd,-agrees-on-special-protocol-assessment-for-phase-3-trials. Michael C Mithoefer et al., “Durability of Improvement in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Absence of Harmful Effects or Drug Dependency after 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Prospective Long-Term Follow-up Study.,” Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 27, no. 1 (January 2013): 28–39, https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881112456611.

[29] Robin L Carhart-Harris et al., “Psilocybin with Psychological Support for Treatment-Resistant Depression: An Open-Label Feasibility Study,” The Lancet Psychiatry 3, no. 7 (July 2016): 619–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7. See also D. E. Nichols, M. W. Johnson, and C. D. Nichols, “Psychedelics as Medicines: An Emerging New Paradigm,” Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 101, no. 2 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.557.

[30] Michael Plant and Lee Sharkey, “High Time For Drug Policy Reform. Part 1/4: Introduction and Cause Summary,” Effective Altruism Forum, 2017, http://effective-altruism.com/ea/1d8/high_time_for_drug_policy_reform_part_14/.

[31] Sidney H. Kennedy et al., “Deep Brain Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression: Follow-Up After 3 to 6 Years,” American Journal of Psychiatry 168, no. 5 (May 1, 2011): 502–10, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10081187.

[32] J Brunelin et al., “Efficacy of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (RTMS) in Major Depression: A Review,” L’Encephale 33, no. 2 (2007): 126–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-7006(07)91542-0.

[33] Alejandro Adler, “Teaching Well-Being Increases Academic Performance: Evidence From Bhutan, Mexico, and Peru,” Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations, January 1, 2016, https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1572.

[34] I’ve put all the calculations for the cost-effectiveness of both GiveDirectly and StrongMinds, including references, in the following spreadsheet: Michael Plant, “Life Satisfaction Impact of Treating Mental Health vs Alleviating Poverty,” 2018, n.d., https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1FcpfiP6P-nxJ7ilqOH0Vv-6TwYdsWc2bOtWLvBmt8wM/edit#gid=0.

[35] Johannes Haushofer, James Reisinger, and Jeremy Shapiro, “Your Gain Is My Pain: Negative Psychological Externalities of Cash Transfers, Working Paper,” 2015.

[36] Andrew E. Clark, “Happiness, Income and Poverty,” International Review of Economics 64, no. 2 (June 21, 2017): 145–58, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-017-0274-7.

[37] Clark, Andrew E., Natavudh Powdthavee, Sarah Flèche, Richard Layard, and George Ward. The Origins of Happiness : The Science of Well-Being over the Life Course, 2018.

[38] Johannes Haushofer and Jeremy Shapiro, “THE LONG-TERM IMPACT OF UNCONDITIONAL CASH TRANSFERS: EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE FROM KENYA,” 2018, http://jeremypshapiro.com/papers/Haushofer_Shapiro_UCT2_2018-01-30_paper_only.pdf.

[39] Available at: https://blog.givewell.org/2018/05/04/new-research-on-cash-transfers/

[40] A list GiveWell top charities is available here: https://www.givewell.org/charities/top-charities

[41] Plant, “Life Satisfaction Impact of Treating Mental Health vs Alleviating Poverty.” https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1FcpfiP6P-nxJ7ilqOH0Vv-6TwYdsWc2bOtWLvBmt8wM/edit#gid=0. Note the impact is nearly identical whether an assuming of a constant benefit of four years (i.e. the inference for Wiles et al. 2016) or if we assume a 75% annual retention of benefits, which is the method taken by Halstead and Snowden, “Cause Area Report: Mental Health”, Founders Pledge, https://founderspledge.com/research/Cause%20Report%20-%20Mental%20Health.pdf

[42] GiveWell "2018 Cost-effectiveness analysis -version 4" states that 2% of the cost-effectiveness of the deworming charities (DtW, SCI, Sightsavers, END) comes from 'short-term health effects' and 98% from 'eventual income and consumption gains'. See Results tab in this spreadsheet: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1moyxmsn4UjhH3CzFJmPwAN7LUAkmmaoXDb6bdW3WILg/edit#gid=1364064522.

[43] Michael Plant, “Are You Sure You Want To Donate To The Against Malaria Foundation?,” Effective Altruism Forum, 2016, http://effective-altruism.com/ea/14k/are_you_sure_you_want_to_donate_to_the_against/.

[44] “The Meat-Eater Problem - Effective Altruism Concepts,” accessed September 21, 2018, https://concepts.effectivealtruism.org/concepts/the-meat-eater-problem/.

[45] Hilary Greaves, “Optimum Population Size,” in Oxford Handbook of Population Ethics, ed. Arrhenius, Bykvist, and Campbell (Oxford University Press, n.d.).

[46] GiveWell, “2018 GiveWell Cost-Effectiveness Analysis — Version 4,” 2018, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1moyxmsn4UjhH3CzFJmPwAN7LUAkmmaoXDb6bdW3WILg/edit#gid=1364064522.

[47] Helliwell, Layard, and Sachs, World Happiness Report 2017 p28

[48] Plant, “Life Satisfaction Impact of Treating Mental Health vs Alleviating Poverty.” https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1FcpfiP6P-nxJ7ilqOH0Vv-6TwYdsWc2bOtWLvBmt8wM/edit#gid=0.

[49] For a summary of the problems of population ethics, see Hilary Greaves, “Population Axiology,” Philosophy Compass, 2017. Note Greaves is unsympathetic to person-affecting views.

[50] Jan Narveson, “Moral Problems of Population,” The Monist, 1973, 62–86.

[51] See Parfit, Reasons and Persons, part 4, 1984.

[52] Gustav Arrhenius, “An Impossibility Theorem for Welfarist Axiologies,” Economics & Philosophy 16, no. 2 (2000): 247–66.

[53] Gregory Lewis, “The Person-Affecting Value of Existential Risk Reduction,” Effective Altruism Forum, 2018, http://effective-altruism.com/ea/1n0/the_personaffecting_value_of_existential_risk/.

[54] Felicia Marie Knaul et al., “Alleviating the Access Abyss in Palliative Care and Pain Relief-an Imperative of Universal Health Coverage: The Lancet Commission Report.,” Lancet (London, England) 0, no. 0 (October 11, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8.

[55] Plant and Sharkey, “High Time For Drug Policy Reform. Part 1/4: Introduction and Cause Summary.”

Hi Michael! I'm an EA from Sheffield. Thank you for all this! :)

I just wanted to introduce into this discussion some broader critiques about the concept of 'global mental health'. Because I think this article rests on some fundamental assumptions about the 'universalism' of mental disorders, such as depression. Assumptions like this are increasingly regarded as problematic by many critical psychiatrists and anthropologists. I will split these into three main criticisms - firstly to do with the framing of the problem of global mental health, then the proposed solutions. This is all very relevant to arguments about scale, neglectedness, tractability and your example of the StrongMinds intervention. ..The final section is about the nature of the global mental health movement and may be less directly relevant but worth putting down anyway!

I think it's super important that we engage with these debates !!!

Critiques of the 'PROBLEM'

The most widely cited prevalence figures on mental disorders globally are sourced from the WHO World Mental Health Survey (Kessler et al., 2009). This is based on diagnosis using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, which assesses mental disorder based on criteria from the US Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM), and the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (Kessler et al., 2009). These classification systems were both developed in the ‘West’, and are representative of ‘Western psychiatry’ – which this essay defines as “psychiatry developed in specific high-income countries of the Global North” (Mills, 2014a, p. 2). Diagnoses used in the World Mental Health Survey are therefore defined by Western psychiatric nosology.

However, decades of anthropological and ethnographic research suggests that understanding, classification, presentation, and prognosis of ‘mental disorders’ varies greatly between cultures (Summerfield, 2012). As a result, the universal application of Western classifications is regarded by critics as deeply problematic. Fernando (2012), for instance, writes of the ‘etic-emic balance’. The term ‘etic’ refers to the approach of studying behaviours from outside a culture, aimed at finding broad culture-general patterns. ‘Emic’, however, refers to the approach of studying behaviours from within a culture, aimed at understanding culture-specific aspects. Fernando argues that the ‘etic-emic balance’ is “largely missing” from current GMH model, which leans heavily towards an ‘etic’ approach of identifying culture-general patterns, whilst importing Western measures to other cultures – in what constitutes an ‘imposed etic’ (Fernando, 2012, p. 401).

Arthur Kleinman has been making similar observations on the pitfalls of cross-cultural psychiatric research for over thirty years – accusing mainstream research of regularly committing a ‘category fallacy’. He describes a ‘category fallacy’ as:

The reification of a nosological category developed for a particular cultural group that is then applied to members of another culture for whom it lacks coherence, and its validity has not been established (Kleinman, 1987, p. 452).

Kleinman (1987) argues that rather than using Western nosological categories, experiences of distress globally may be better understood through the anthropological model of ‘idioms of distress’: “culturally prescribed ways of communicating that someone feels bad and/or unhappy” (Ventevogel, 2016, p. 247). These ‘idioms of distress’, though perhaps sharing similarities with Western categories, should not automatically be assumed to align with them in a meaningful way. Many authors argue that today’s GMH approaches continually misalign ‘idioms of distress’ into Western categories, hence subscribing to Kleinman’s ‘category fallacy’ (Miller et al., 2009; Summerfield, 2013; Mills, 2014a; Ventevogel, 2016). It is argued that cultural understandings are too often an “after-the-fact consideration”, when in fact they ought to represent the starting point for capturing the experiences that mental health research seeks to understand (Bass, Bolton and Murray, 2007, p. 918).

For many critics, these epistemological problems are fundamental – so far as to render claims about worldwide prevalence of mental disorders invalid (Fernando, 2012). In fact, Summerfield (2013) argues that the very concept of ‘global’ mental health should be considered an oxymoron for such reasons.

Critiques of the 'SOLUTIONS'

Secondly, there are criticisms of ‘The Solutions’ as presented by GMH advocates – that is, the urgent scaling up of evidence-based interventions worldwide (Patel et al., 2018). The roots of many criticisms lie in the ways in which these evidence-based ‘Solutions’ may act as a vehicle for exporting the ‘biomedical model’ which dominates Western psychiatry, with potentially harmful consequences.

This ‘biomedical model’ understands mental illness as the result of “faulty mechanisms”, arising from “abnormal physiological and psychological events occurring within the individual”, which – like the rest of medicine - can be understood with causal logic, and captured with scientific tools (Bracken et al., 2012, p. 430). This model works within a positivist orientation, which critical psychiatrists describe as the ‘technological paradigm’. Many critical psychiatrists assert that the primacy of this paradigm is problematic in the West, let alone elsewhere. It is argued that the ‘technological paradigm’ does a disservice to the specialty through reducing its scope to that of an ‘applied neuroscience’. This approach, termed by some as ‘psychiatric reductionism’, valorises the individual brain and specific technical interventions (such as medication or CBT), whilst comparatively neglecting the complicated interplay of psychological, social and cultural forces which underlie mental disorder (Bracken et al., 2012). Generally then, it seems that the application of the Western psychiatric model is not without its controversies.

Nevertheless, the GMH movement was born out of this dominant paradigm, and so naturally promotes ‘Solutions’ that are reflective of it. This is seen as problematic for several reasons.

One concern is that the GMH movement, through exporting the ‘biomedical model’, may become an “unwitting Trojan horse” for mass medicalisation in the Global South (Whitley, 2015, p. 288) – paving the way for exploitation by large pharmaceutical companies with corporate interests to market psychotropic agents in ways that are potentially harmful (Fernando, 2011).

More broadly, there is serious concern over how GMH is framed, within the ‘biomedical model’ – or what Mills calls the “GMH within-brain approach” (Mills, 2014a, p. 11). This model puts the focus on individuals, and so accordingly promotes technical, individual solutions. This idea of effective technical solutions is a strong narrative of the GMH movement - well captured, for example, by the WHO’s assertion that “unlike many large scale international problems, a solution for depression is at hand” in the form of amitriptyline, fluoxetine, or talking therapies, as guidelines recommend (Marcus et al., 2012, p. 8; WHO, 2016b). However, framing GMH in this way can have the result of deflecting attention away from crucially important determinants of mental health which go far beyond individuals.

The anthropological theory of ‘social suffering’ helps to emphasise the profound influence of these wider factors - conceiving of suffering in the context of “what political, economic and institutional power does to people” (Kleinman, Das and Lock, 1997, p. 9). A shocking example is illustrated by Mills (2014b), in her chapter ‘Suicide Notes to the State’. Mills describes the devastating impact of agricultural reforms on small-scale farmers in India, which have led to socioeconomic crisis and unprecedented levels of suicides among this group – 87% of which are linked to debts (Mills, 2014b). While farmers write suicide notes to the government, GMH calls for increasing their access to anti-depressants. Mills argues that reducing intervention down to this biochemical level completely fails to address the systemic ways in which global power imbalances and socioeconomic inequalities are making people’s lives unliveable.

Additionally, Paul Farmer’s (2009) theory of ‘structural violence’ is useful in describing how macro-level social arrangements can systematically put individuals and populations in harm’s way; thereby creating the conditions for both psychical and mental suffering.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the most recent Lancet Commission went some way towards responding to these criticisms, with authors acknowledging that the “biomedical framing of the treatment gap has attracted criticism from some scholars and activists”. The report notably placed stronger emphasis on the “social determinants of mental health”, as well as the need to strike a balance between pharmacological and psychological interventions - steps which were met with approval by several of the movement’s critics (Patel et al., 2018, pp. 1557, 1560).

Critiques of the nature of the 'global mental health' movement

Thirdly, the nature of the GMH movement itself has come under attack from several quarters.

Through a postcolonial lens, Mills (2014a) calls for a wider analysis of the mechanisms which allow the ‘global norms’ for mental health, as stated by GMH and WHO, to circulate as ‘true’, whilst foreclosing other ways of thinking from circulating. Indeed, the movement is seen by Mills and others to constitute a form of ‘psychiatric imperialism’ (Summerfield, 2013; Christopher et al., 2014; Mills, 2014a).

These critiques are closely tied up in global power relations, and both Kleinman (2010) and Summerfield (1999) invoke the theories of Foucault in the context of GMH. Foucault theorized an inseparable relationship between knowledge and power - suggesting that those in control can create norms and categories which become the basis of knowledge. This knowledge can then serve to legitimise political and socioeconomic conditions, as modes of power (Gutting and Oksala, 2003). Foucault’s knowledge/power relationship seems highly relevant to previous critiques of GMH – including notions of category fallacies, dominant paradigms, and Western psychiatric hegemony.

The aforementioned call by Patel to make “mental health for all a reality” therefore merits deeper questioning. In this discipline, whose ‘reality’ counts? Who has the power to define it? GMH’s current ‘psychiatric reductionism’, Mills (2014a) argues, is far from offering a reality check. On the contrary - GMH proceeds to put people in biological and epidemiological boxes, whilst failing to adequately understand or represent the complex multiple realities of their lived experiences.

REFERENCES

Bass, J. K., Bolton, P. A. and Murray, L. K. (2007) 'Do not forget culture when studying mental health', The Lancet, 370(1), p. 918.

Bracken, P., Thomas, P., Timimi, S., Asen, E., Behr, G., Beuster, C., et al. (2012) 'Psychiatry beyond the current paradigm', British Journal of Psychiatry, 201, pp. 430-434.

Christopher, J. C., Wendt, D. C., Marecek, J. and Goodman, D. M. (2014) 'Critical Cultural Awareness Contributions to a Globalizing Psychology', American Psychology, 69(7), pp. 645-655.

Farmer, P. (2009) 'On Suffering and Structural Violence: A View from Below', Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts, 3(1), pp. 11-28.

Fernando, G. A. (2012) 'The roads less traveled: Mapping some pathways on the global mental health research roadmap', Transcultural Psychiatry, 49(3), pp. 396-417.

Fernando, S. (2011) 'A 'global' mental health program or markets for Big Pharma?', Open Mind, 168(1), p. 22.

Gutting, G. and Oksala, J. (2003) Michel Foucault: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/foucault/#ClasRepr (Accessed: 3 February 2019).

Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Chatterji, S., Lee, S. and Üstün, T. B. (2009) 'The World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys', Psychiatrie (Stuttg), 6(1), pp. 5-9.

Kirmayer, L. J. (2012) 'Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health: Epistemic communities and the politics of pluralism', Social Science & Medicine, 75(6), pp. 249-256.

Kirmayer, L. J. and Pedersen, D. (2014) 'Toward a new architecture for global mental health', Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(6), pp. 759-776.

Kleinman, A. (1987) 'Anthropology and Psychiatry: The Role of Culture in Cross-Cultural Research on Illness', British Journal of Psychiatry, 151(4), pp. 447-454.

Kleinman, A., Das, V. and Lock, M. (1997) Social suffering. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press.

Mills, C. (2014a) Decolonizing Global Mental Health: The psychiatrization of the majority world. Concepts for Critical Psychology New York: Routledge.

Mills, C. (2014b) ''Harvesting Despair' - Suicide notes to the state and psychotropics in the post', Decolonizing Global Mental Health: The psychiatrization of the majority world Concepts for critical psychology. New York: Routledge.

Mulder, R., Singh, A. B., Hamilton, A., Das, P., Outhred, T., Morris, G., Bassett, D., et al. (2018) 'The limitations of using randomised controlled trials as a basis for developing treatment guidelines', Evidence-Based Mental Health, 21(1), pp. 4-6.

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., et al. (2018) 'The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development', The Lancet, 392, pp. 1553-1598.

Summerfield, D. (1999) 'A critique of seven assumptions behind psychological trauma programmes in war-affected areas', Social Science & Medicine, 48(10), pp. 1449-1462.

Summerfield, D. (2012) 'Afterword: Against "global mental health"', Transcultural Psychiatry, 49(3), pp. 519-530.

Summerfield, D. (2013) '"Global mental health" is an oxymoron and medical imperialism', British Medical Journal, 346, p. 3509.

Ventevogel, P. (2016) Borderlands of mental health: Explorations in medical anthropology, psychiatric epidemiology and health systems research in Afghanistan and Burundi. PhD thesis. University of Amsterdam. Geneva. Available at: https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/2769192/176799_Ventevogel_Thesis_Borderlands_of_mental_health.pdf (Accessed: 17 January 2019).

Ventevogel, P. and Faiz, H. (2018) 'Mental disorder or emotional distress? How psychiatric surveys in Afghanistan ignore the role of gender, culture and context', Intervention, 16(3), pp. 207-214.

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Flaxman, A. D., Johns, N., Burstein, R., Murray, C. J. L. and Vos, T. (2013) 'Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010', The Lancet, 382, pp. 1575-1586.

Whitley, R. (2015) 'Global Mental Health: concepts, conflicts and controversies', Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24(1), pp. 285-291.