By Robert Wiblin | Watch on Youtube | Listen on Spotify | Read transcript

Episode summary

So if you take as your baseline that the December 2024 announcement was just a codification of what was happening anyway — in terms of OpenAI just like acting like a for-profit that sort of had a nonprofit attached to it in some weird way — then I think the outcome is a lot better than that. … If your baseline for comparison is an idealistic view of what OpenAI was meant to be when it was founded in 2015, I think this is in some sense a catastrophe. We’ve just lost a lot, as the public, of what we should have had if OpenAI had been the better version of itself it was always supposed to be. — Tyler Whitmer |

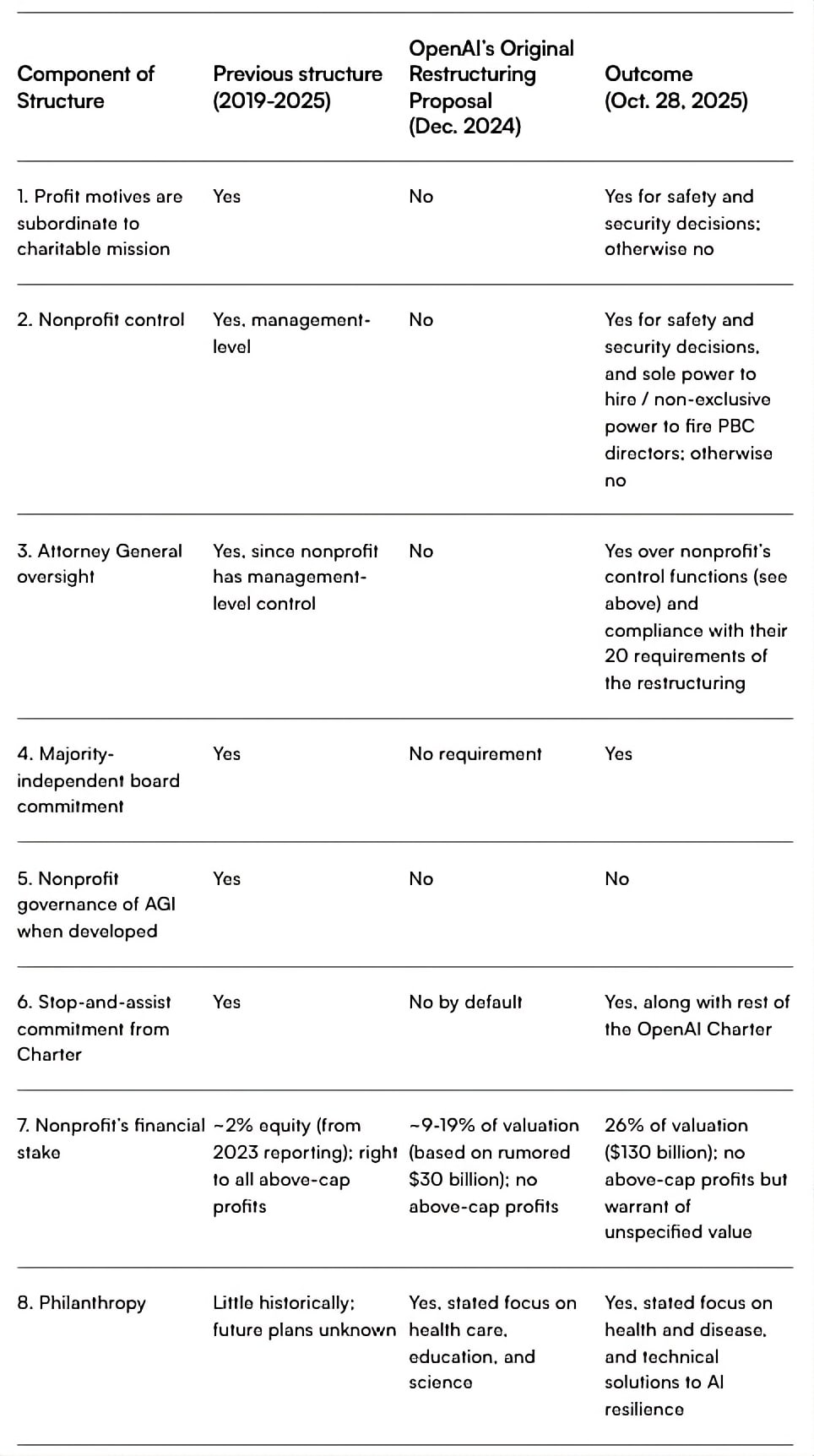

Last December, the OpenAI business put forward a plan to completely sideline its nonprofit board. But two state attorneys general have now blocked that effort and kept that board very much alive and kicking.

The for-profit’s trouble was that the entire operation was founded on the premise of — and legally pledged to — the purpose of ensuring that “artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity.” So to get its restructure past regulators, the business entity has had to agree to 20 serious requirements designed to ensure it continues to serve that goal.

Attorney Tyler Whitmer, as part of his work with Legal Advocates for Safe Science and Technology, has been a vocal critic of OpenAI’s original restructure plan. In today’s conversation, he lays out all the changes and whether they will ultimately matter:

After months of public pressure and scrutiny from the attorneys general (AGs) of California and Delaware, the December proposal itself was sidelined — and what replaced it is far more complex and goes a fair way towards protecting the original mission:

- The nonprofit’s charitable purpose — “ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity” — now legally controls all safety and security decisions at the company. The four people appointed to the new Safety and Security Committee can block model releases worth tens of billions.

- The AGs retain ongoing oversight, meeting quarterly with staff and requiring advance notice of any changes that might undermine their authority.

- OpenAI’s original charter, including the remarkable “stop and assist” commitment, remains binding.

But significant concessions were made. The nonprofit lost exclusive control of AGI once developed — Microsoft can commercialise it through 2032. And transforming from complete control to this hybrid model represents, as Tyler puts it, “a bad deal compared to what OpenAI should have been.”

The real question now: will the Safety and Security Committee use its powers? It currently has four part-time volunteer members and no permanent staff, yet they’re expected to oversee a company racing to build AGI while managing commercial pressures in the hundreds of billions.

Tyler calls on OpenAI to prove they’re serious about following the agreement:

- Hire management for the SSC.

- Add more independent directors with AI safety expertise.

- Maximise transparency about mission compliance.

There’s a real opportunity for this to go well. A lot … depends on the boards, so I really hope that they … step into this role … and do a great job. … I will hope for the best and prepare for the worst, and stay vigilant throughout.

Host Rob Wiblin and Tyler discuss all that and more in today’s episode.

This episode was recorded on November 4, 2025.

Video editing: Milo McGuire, Dominic Armstrong, and Simon Monsour

Audio engineering: Milo McGuire, Simon Monsour, and Dominic Armstrong

Music: CORBIT

Coordination, transcriptions, and web: Katy Moore

The interview in a nutshellTyler Whitmer, a commercial litigator and founder of Legal Advocates for Safe Science and Technology (LASST), explains how the California and Delaware attorneys general (AGs) rejected OpenAI’s December 2024 restructure proposal. While he argues the public suffered a “poignant loss” by ceding exclusive nonprofit control over AGI, the AGs forced major concessions that are a significant win for safety and oversight compared to the “flagrant misappropriation” that was originally proposed. 1. The AGs enshrined the nonprofit’s safety mission and controlOpenAI’s original proposal would have sidelined the nonprofit, turning it into a minority shareholder focused on generic grantmaking. The AGs rejected this, forcing a new structure that preserves the nonprofit’s power in several key ways:

2. The nonprofit’s Safety & Security Committee (SSC) has real teeth — but may lack the will to use themThe new structure’s primary safety check is the SSC, a committee of the nonprofit board.

3. The biggest loss: The public’s exclusive claim on AGI is goneThis was the one area where Tyler feels the public lost, as the AGs did not successfully intervene.

4. “Scrappy resistance” worked, and continued vigilance is crucialTyler credits public advocacy from groups like his (LASST) for giving the AGs the “wind at their back” and “courage of their convictions” to challenge a “really well-heeled opponent.” The fight now shifts to monitoring this new structure.

|