Saloni will answer the questions in this AMA between 6-8pm BST on July 8th. Leave your questions as comments, and upvote other questions you’d like to see answered.

If you’ve been around EA for a while, and you’re interested in global health, you’ve probably read Saloni Dattani before.

Saloni writes about global health at Our World In Data and is a co-founder and editor of Works in Progress magazine. She’s also recently started a podcast, Hard Drugs, with Jacob Trefethen. She also (somehow) finds time to write a great blog, Scientific Discovery.

She’s recently written on:

- The decline in cancer mortality, and how it’s not all down to decline in smoking.

- How we calculate fertility rates, and why just calculating the total fertility rate leads us astray.

And she delivered a talk at EA Global London on the data that shapes global health.

Question ideas:

For some question ideas (though you can ask her anything), I asked o3 what Tyler Cowen would ask Saloni Dattani. Here are the best questions it spat out:

- Why do reported total fertility rates mislead policymakers, and how would you fix the metric?

- Where are the biggest blind spots in maternal-mortality data, and how should we fill them?

- What single root cause explains the long delay in rolling out a malaria vaccine?

- Which global-health dataset is most underrated, and why?

- Which country gets suicide statistics most wrong, and what are the consequences?

- Editing Works in Progress, what one lesson has most improved the ideas you publish?

- What browser tabs are open on your laptop right now?

- How has bird-watching shaped the way you do science, if at all?

- As head of the WHO for a day, what is the first concrete action you would take?

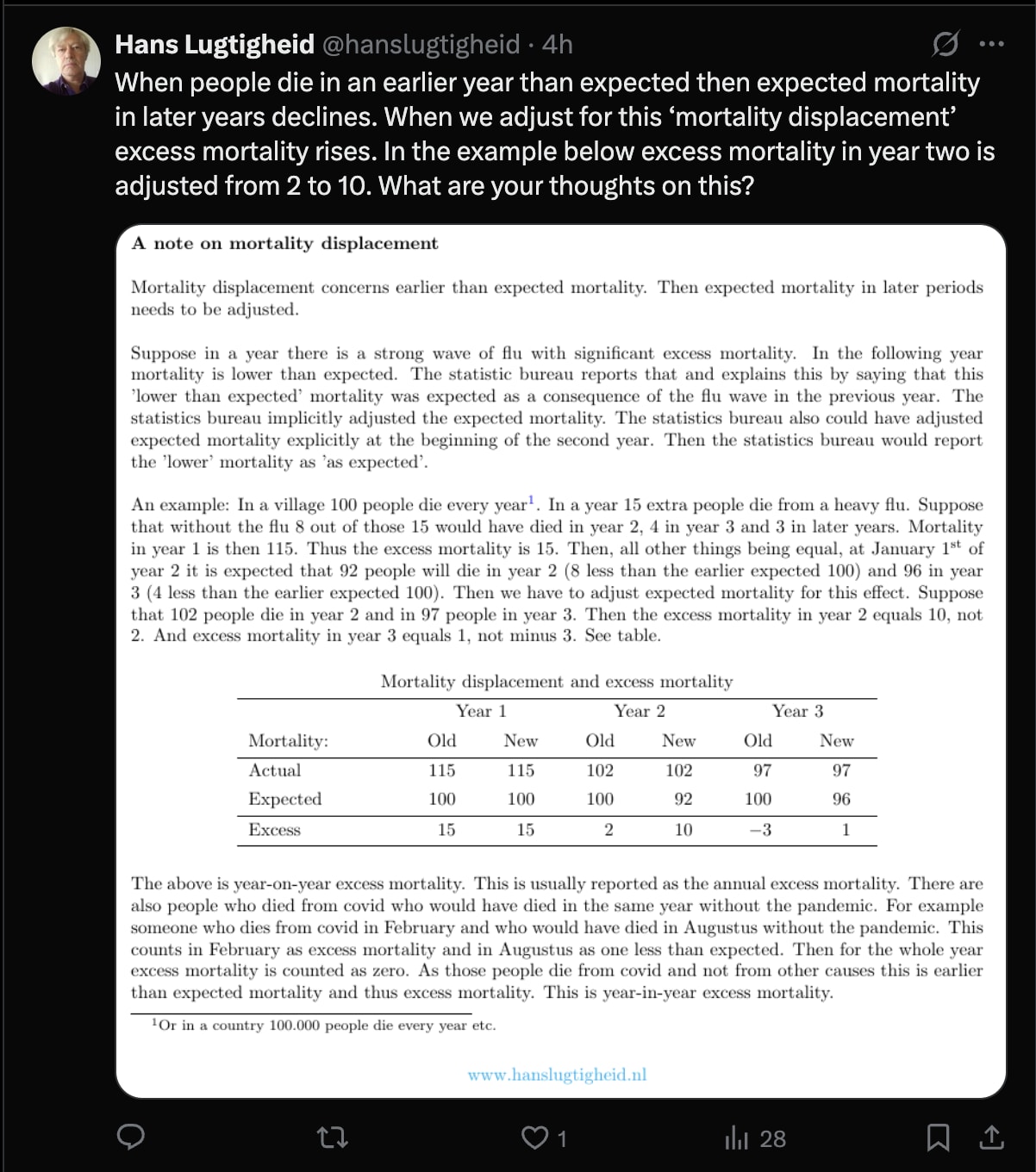

Crossposting some extra questions from Saloni's bluesky post: