Context: I'm an EA with Long Covid and a contributor to a new research organisation aiming to solve Long Covid. Due to my limited capacity, this is in the form of bullet points.

Summary

The scale of Long Covid

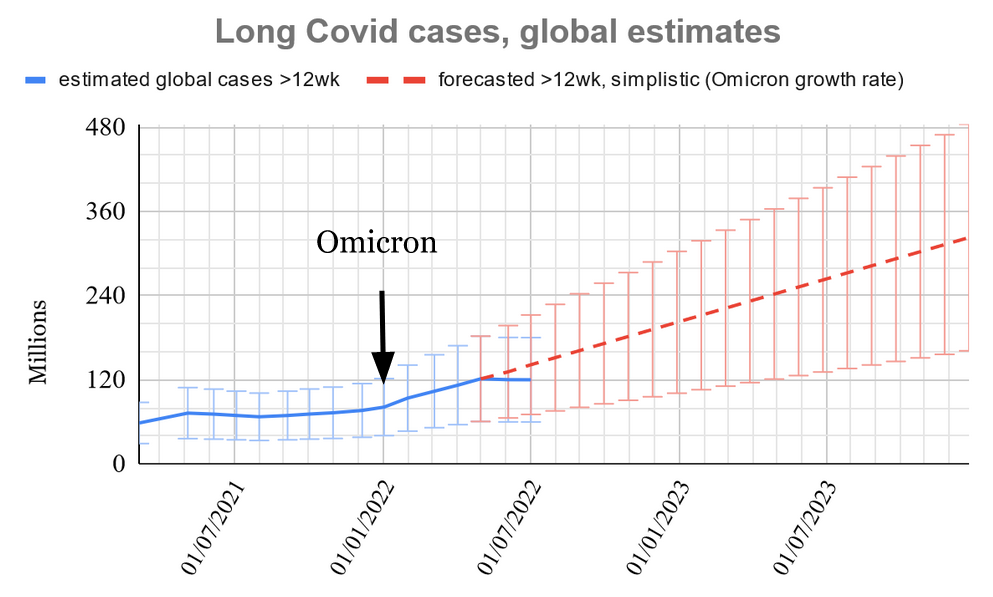

- The scale of Long Covid is large: 120 million (70% confidence interval: 60 mln. to 180 mln.) worldwide as of May 2022

- Due to many infections and limited protection by vaccines, current growth rate appears to be ~120 million/year

- We should expect this rate of disability to have very significant effects on society and economies worldwide

- There is large uncertainty around the true prevalence, thus independent research is valuable

- Health effects after COVID even without direct symptoms ('asymptomatic Long Covid'): brain damage, immune damage, increased mortality → Very concerning trajectory of long-term societal effects

Tractability & Crowdedness

- Symptomatic Long Covid: strongly suggestive evidence that Long Covid is a chronic infection in many cases → can be treated with many therapeutics in development for acute COVID

- Asymptomatic Long Covid: requires prevention

- Quite neglected

Conclusion

- Prevention, treatment, and further cause area research are all impactful

- Comparable to climate change in scale and societal impact, but developing on shorter timescale, more neglected, and (symptomatic Long Covid) is more tractable to solve

Introduction

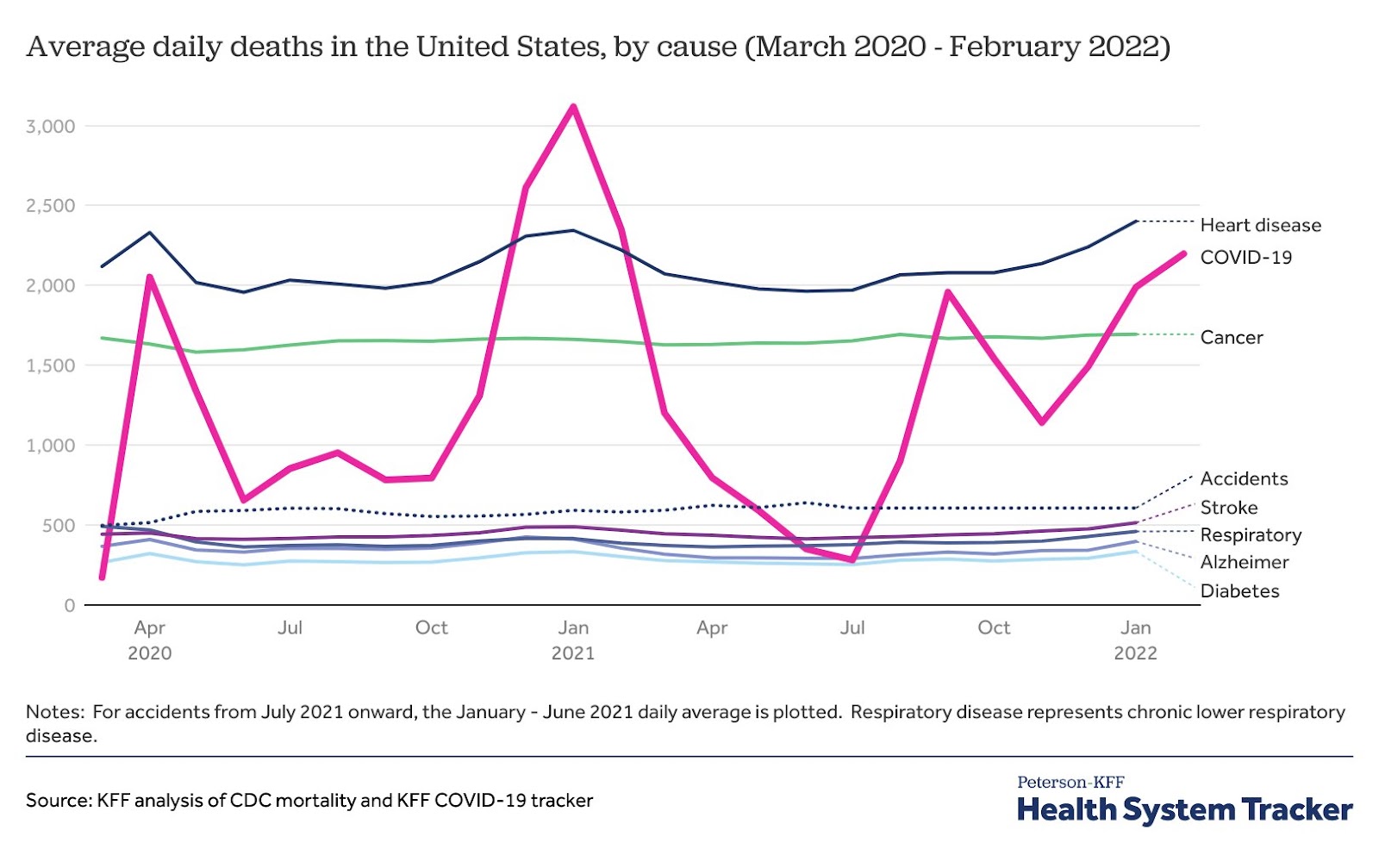

- Focus on deaths has overshadowed disability from Long Covid

- Many viruses/epidemics lead to long-term disease

- In this post, I argue that initial data is convincing enough that Long Covid warrants attention, action, and funding from neartermists

- maybe even longtermists because of broad societal effects

- Exploratory, not in-depth, and I don't pretend to be objective (but I try good faith argumentation)

- I take a cluster-argument approach: many different reasons to believe Long Covid is large and important, even though some sources will not withstand in-depth scrutiny

What is Long Covid?

- I use the following definition: any health effects lasting longer than 3 months that were primarily caused by COVID infection

- Health effects such as (see Wikipedia):

- Vasculitis/endothelial dysfunction

- Neuroinflammation

- Microscopic blood clots

- Reduced oxygen extraction from blood into cells

- Insomnia

- GI issues/gut dysbiosis

- Cognitive impairment

- Post-exertional symptom exacerbation

- Orthostatic intolerance

- Intolerance to stimuli (sounds, light)

- Subset of patients have:

- Myalgic encephalomyelitis (aka "chronic fatigue syndrome", ME/CFS)

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): symptoms increase by sitting/standing upright

- Severity:

- ME/CFS: >0.5 DALYs lost per patient per year. Suicide one of the leading causes of death

- Combination of POTS, ME/CFS, and other health issues is highly disabling. Many patients are housebound or even bedbound and often lie in darkened rooms, lose income, social lives, etc.

- ~1 in 5 patients report not working because of their illness

- High amount of stigma among social circles and medical professionals that it's psychosomatic → worse quality of life

- Although hospitalisation and ICU increase risk of Long Covid, most Long Covid patients had a mild or asymptomatic acute phase

- Pace of research (incl. acute COVID and basic virology) is high, but unfocused.

The scale of Long Covid is large

Two methods to estimate total number of Long Covid cases:

- Sample the population

- Estimate and multiply parameters separately

- How many infections become Long Covid?

- How many Long Covid cases recover within 1 year?

- How many people have been infected?

For simplicity, I use data from Western countries and assume it roughly extrapolates worldwide, except for China[1].

Method 1: population samples

- As of early May 2022, 2.2% of the UK population self-reports to currently suffer from ongoing symptoms for at least 12 weeks, and 1.25% for longer than a year, according to the UK’s Office of National Statistics. Of those, roughly 50% are impaired ‘a little’, and another 20% ‘a lot’.

- Advantages of this dataset: updates monthly, population representative

- Drawbacks: no control group, self report

- Issues with self-report:

- Overestimate/over-attribution possible

- Underestimate/under-attribution: people may not be aware their symptoms are due to COVID (Long Covid can be caused by asymptomatic infection)

- Mid June 2022, US CDC reports 7.5% of the US population currently has symptoms that have lasted longer than 3 months since COVID infection

- Difference with UK ONS: US respondents are asked 'any symptoms since COVID' whereas ONS asks respondents whether they'd describe their symptoms as Long Covid, i.e symptoms after COVID not explained by something else

- If we extrapolate the UK data to the world population minus China and adjust for demographics but nothing else, we arrive at ~120 million cases of Long Covid (> 12 weeks) as of May 2022. (extrapolation, explanation)

- Unfortunately, population samples are becoming less accurate; people are testing less, thus are less likely to know they've had COVID for sure. Any long-term symptoms are consequently attributed less to COVID.

Method 2: assessing parameters separately

- Many numbers for each parameter, no consensus. I don't feel comfortable making a single guesstimate. Instead, I present a collection of numbers for each parameter

a) How many infections turn into Long Covid?

ONS self-reporting survey implies ~12% of people who have had COVID report having symptoms they would describe as ‘Long Covid’ 12 weeks after infection (no control)

- There are many studies done on the prevalence of Long Covid, with estimates ranging widely. Many have methodological issues (no controls, sampling bias)

- The probability of Long Covid is dynamic, changing based on e.g. amount of vaccinations, time since vaccination, antigenic difference between strains in case of multiple infections, number of reinfections

Other large scale studies (mixed rates of vaccination):[2]

- “Malaise and fatigue” reported to be 1.3% higher 6 months after infection in ~74,000 COVID-positive veterans compared to a control group of ~5 million (USDVA[3]). In another study with a similar dataset, 'at least one symptom' after infection was ~5% higher than control group (USDVA)

- Dr. Claire Stevens[4] believes the ONS data is roughly a 2x overestimate, based on the ZOE Study, which reports 2.6% of COVID-positive cases to still have symptoms more than 12 weeks after infection (source)[5]

- In Dutch study, in the COVID-positive group (n > 4,000), people reporting at least 1 symptom was 12.7% higher (21.4% vs. 8.7%) than the control group (n > 8,000), 90-150 days after infection

- CDC reports almost 1 in 5 (19%) will develop Long Covid after infection. No controls

Related numbers

- 12.7% of patients with COVID-19 shed fecal viral RNA 4 months after diagnosis, 3.8% at 7 months, and 0% at 10 months. Presence of faecal SARS-CoV-2 RNA is associated with gastrointestinal symptoms

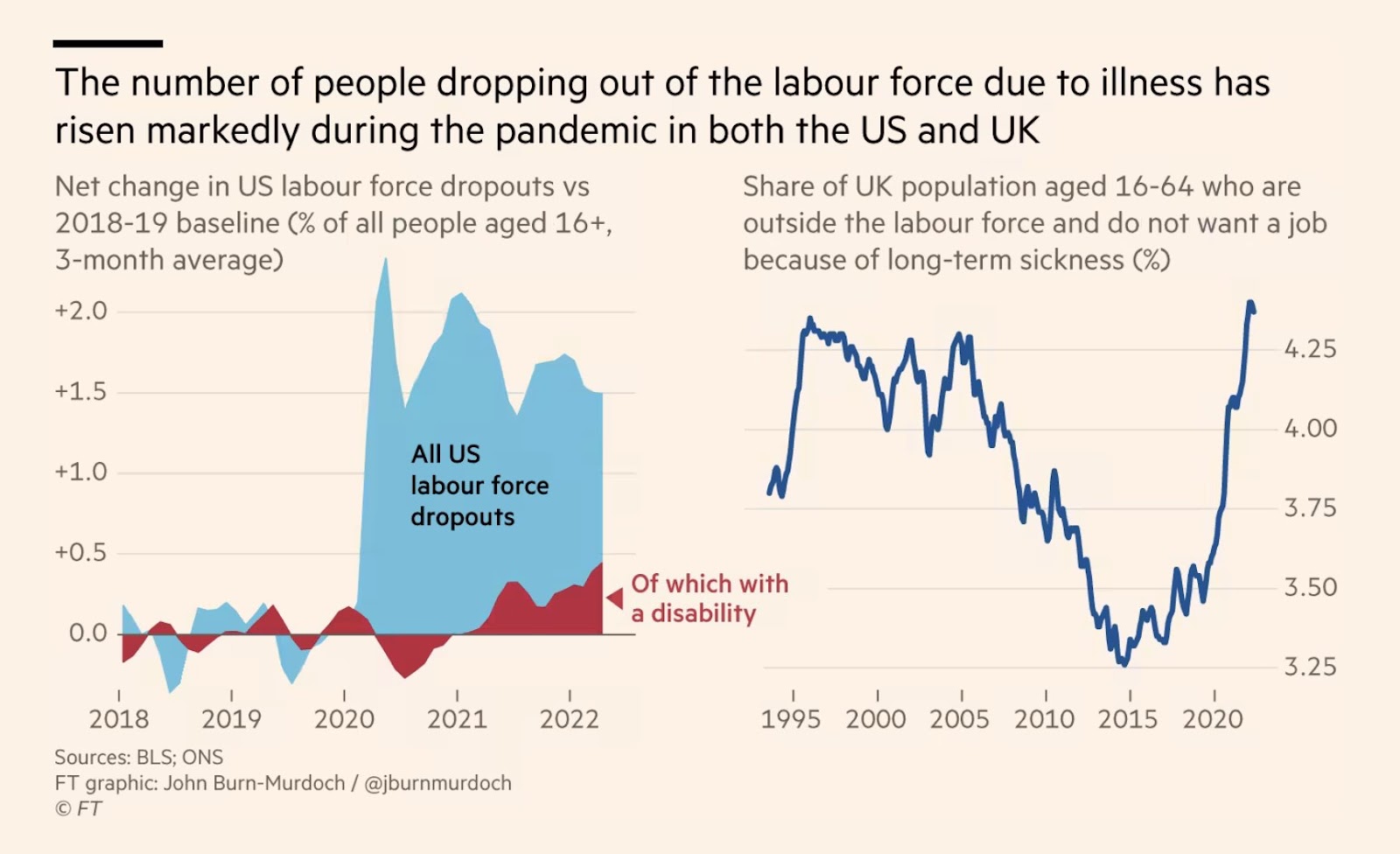

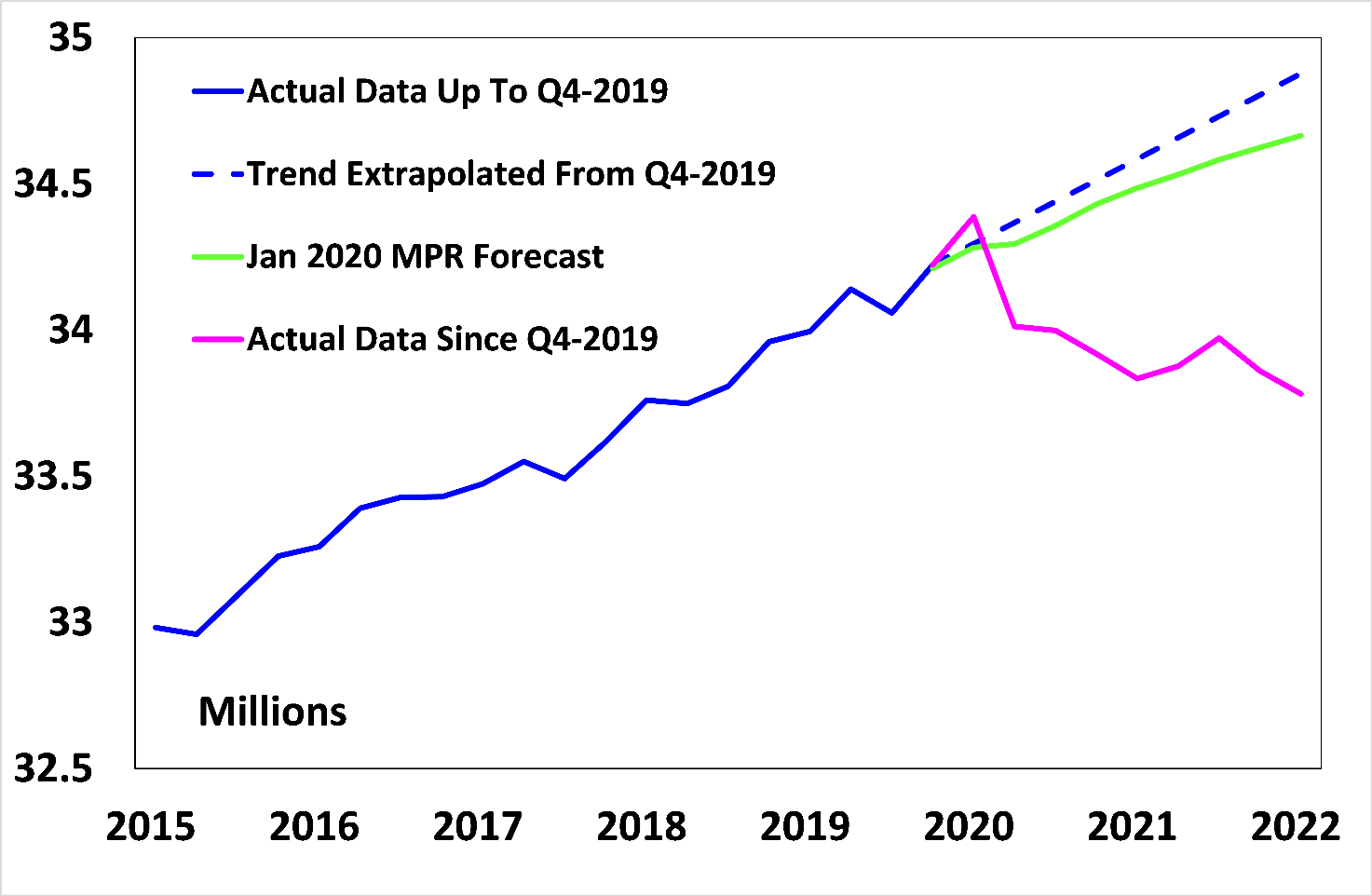

- Between Q4-2019 and Q1-2022, the number of people aged 16-64 years that are outside the workforce and do not want a job because of (any) long-term illness has risen by 320,000 (0.8% of the 16-64 age population) and 30,000 because of short-term illness (0.07%). (Bank of England)

- Note that this is 1-2x more than the amount of people reporting they're "impaired a lot"[6]

Long Covid risk is changing over time

- This makes the analysis substantially more difficult

- Ideally, one would calculate a weighted risk adjusted for the following

- vaccines

- reinfections

- new strains

Vaccines

- Vaccination doesn't fully protect against, but reduces the risk of developing Long Covid by 15-85%

- 15% (USDVA)

- ~50–67% (early 2022 review study)

- 75% (2 vaccinations) or 84% (3 vaccinations); (cohort study)

- Personally, 50-75% reduction seems a reasonable estimate

- Increasing vaccination rates (UK) may dampen growth of Long Covid, if boosters have good uptake

- The higher vaccination efficacy, the less accurate is extrapolation from UK to world (underestimates Long Covid in low vaccine rate countries)

Reinfections

- Previous infection confers little long-term protection (USDVA), and new variants probably will compete on escaping prior immunity (see antigenic sin, antigenic drift).

New strains

- I see no theoretical reason to believe there's lower risk, all things equal

- I would expect variants with better immune evasion to 1) generate a milder acute phase, 2) be more likely to establish viral reservoirs

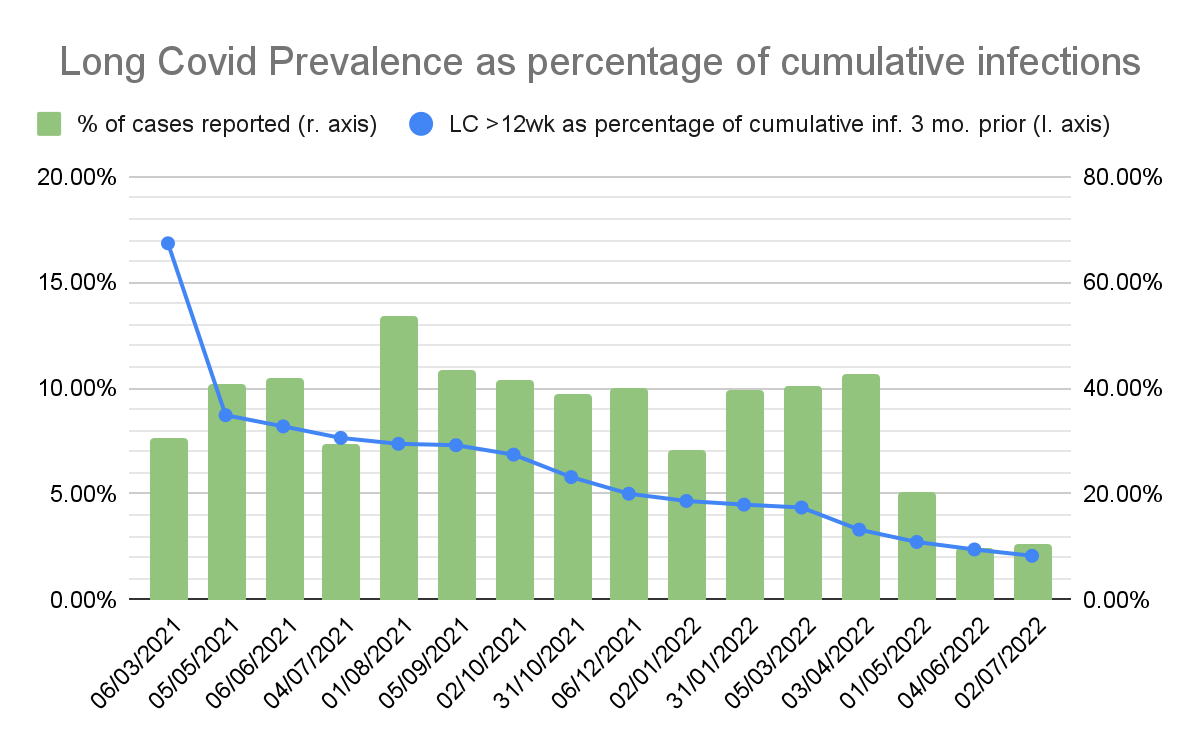

- ONS reported lower Long Covid incidence for Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 compared to Delta (odds ratios of 0.5 and 0.6, respectively) for double vaccinated individuals. For triple vaccinated individuals, there was no difference.

- Unfortunately, the above graph contains a confounding factor: we should expect a cumulative rate to always grow faster (because people can count more than once) than a prevalence rate. But I was unable to access data on new Long Covid cases per month.

- The drop in the last 3 months can be explained by reduced testing.

- The relative prevalence cannot be directly compared to the probabilities mentioned in section a), because the blue line does not include people who developed Long Covid but have already recovered.

- My takeaway: I think it is unlikely the rate of Long Covid will drop further over time, compared to April 2022, unless:

- Significantly better vaccines are rolled out

- A new variant is extraordinarily different

b) How many Long Covid patients recover within 1 year of symptom onset?

- To predict Long Covid prevalence longer than 3 months, we need to know how many recover

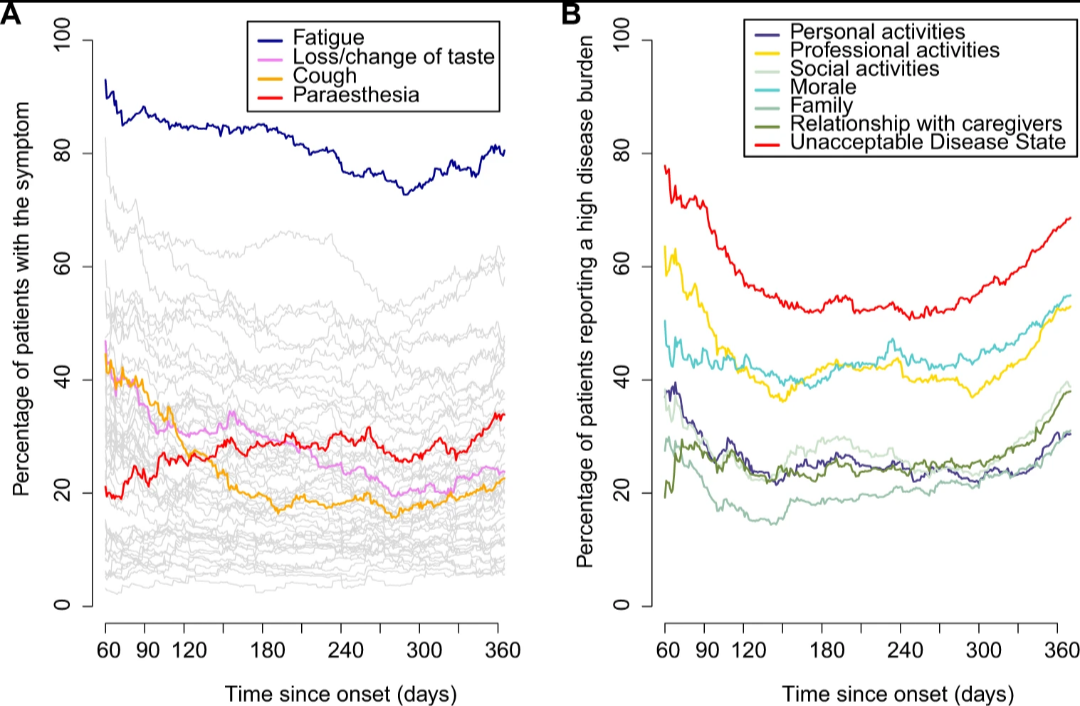

- Recovery rates after 3 months aren't good in ONS data: -11% to +37% have recovered 9 months later

- Yes, that's a negative recovery rate: in some months, more people are sick for 12 months compared to sick for 3 months, 9 months earlier.[7]

- I believe that the actual recovery rate is probably higher

- I believe recovery after 1 year to be low (<10%/year). I'm ignoring that for simplicity.

- Prospective cohort study (n=968) by Tran et al. (2022) had 15% full remission between month 2 and month 12

c) Estimating cumulative infections

- Intuitive heuristic: average amount of infections per person

- E.g. if it's 0.2, you should expect to see 1 in 5 of your social network to have had 1 infection. If it's 1.2, you should expect most people you know to have been infected, and some people more than once.

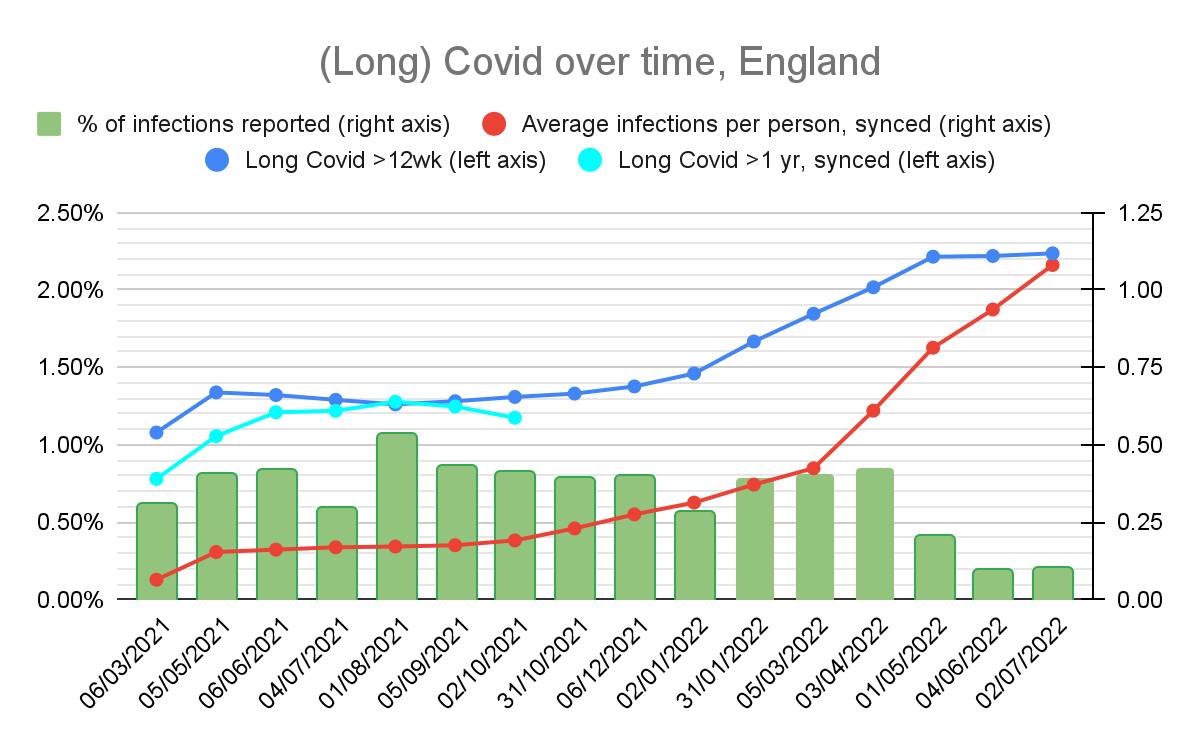

- In the graph below, I have

- summed the incidence rates of ONS infection survey (large scale random sampling) for England[8]

- I adjusted the numbers for a false negative rate of 15%[9].

- I shifted these by 3 months. Infections at x = April 2022 are from January 2022. Now, the Long Covid prevalence (which lags by 3 months) can be visually compared to infections 3 months earlier.

- Calculated the Long Covid Prevalence for symptoms lasting at least 12 weeks

- Calculated the Long Covid prevalence for symptoms lasting at least 1 year.

- I shifted these by 9 months later for visual comparability. Prevalence at x = March 2021 reflect cases reported at December 2021.

- Calculated the percentage of cases that were reported, calculated by dividing the reported cases by the estimated cases based on the Infection Survey.

- I am assuming this correlates to some extent with at-home testing.

- summed the incidence rates of ONS infection survey (large scale random sampling) for England[8]

- First things first: why did Long Covid cases flatline in the last 2 months?

- As we can see, testing has massively decreased. People in the ONS Long Covid survey are asked about lasting symptoms from covid. Based on this data, I believe the flatlining in the last 2 months is caused by people not knowing their long-lasting symptoms are from covid.

- Unfortunately, this means

- We can not use the ONS data to keep track of Long Covid prevalence in the future

- More and more people are going to have unexplained symptoms

- Now, how many people have been infected?

- At the start of April 2022, roughly 2.02% had Long Covid in the UK, as the result of 0.61 infections/person. This means a 3.31% prevalence:infection rate.

- Latest known infections are 1.47/person (mid June). I think we're currently (mid August) at ~1.8.

- Note again that 3.3% is not directly comparable to the figures at a). However, it definitely seems to be in the same ballpark.

- My conclusion: UK ONS prevalence seems reasonable median estimate, but we should have wide uncertainty interval

- In my personal estimate, I have the UK ONS data as median, and a 70% confidence interval of 0.5x to 1.5x

We should expect many more cases

[UPDATE NOV 2022: turns out this forecast was wrong and incidence (new cases) is decreasing, severity of new cases is decreasing, and significant amounts of people are recovering in the <1 year category. I now expect prevalence to be stagnating/decreasing for a while, and then slowly growing over the next few years.]

- As things currently look, there will still be many (re)infections.

- Waning vaccine immunity and limited uptake of further boosters may further dampen the protective effect of vaccines on Long Covid prevalence

- The sheer amount of infections by omicron variants will still lead to many more cases of Long Covid.

- The growth rate of Long Covid prevalence might decrease as most at risk patients already developed Long Covid, but I would be surprised if this has substantial effects on the growth rate

- This will only stop if the pandemic is curbed, via either next generation vaccines that prevent infection and create herd immunity, or large uptake of therapeutics that prevent development of Long Covid (unlikely)

- I extrapolated UK ONS numbers to world population excluding China, adjusted for demographics and nothing else (data, explanation).

- If we ignore the invalid growth rates of the last 2 months, the average growth rate in 2022 (since Omicron BA.1) is ~10 million/month. If that rate holds, this (simplistic) model predicts the following by the end of 2023.

- Please note that these are not my all-things-considered predictions.

- The confidence bars represent my 70% confidence that the UK data this is based on, falls within this interval.

- They don't account for a change in pandemic response, effective therapeutics, effective vaccination, or different vaccination rates worldwide.

- However, I do think it’s a reasonable median scenario to assume

- Vaccination rate worldwide is definitely lower than UK, so the extrapolation is more likely to be higher than the median of this extrapolation.

Effects of Long Covid on society

Note: this part is more a case for reduction/prevention of cases, rather than for treatment of viral persistence

Health effects of 'asymptomatic Long Covid'

- There are concerns of long-term complications that do not initially manifest in symptoms (we can call this ‘asymptomatic Long Covid’).

- 2.4% increased risk of death (USDVA)

- Prior COVID infection appears to increase risk of cardiovascular events by 50-70% (USDVA), increasing even in non-risk groups

- COVID infection may lead to ongoing (mild) immunosuppression and T cell exhaustion

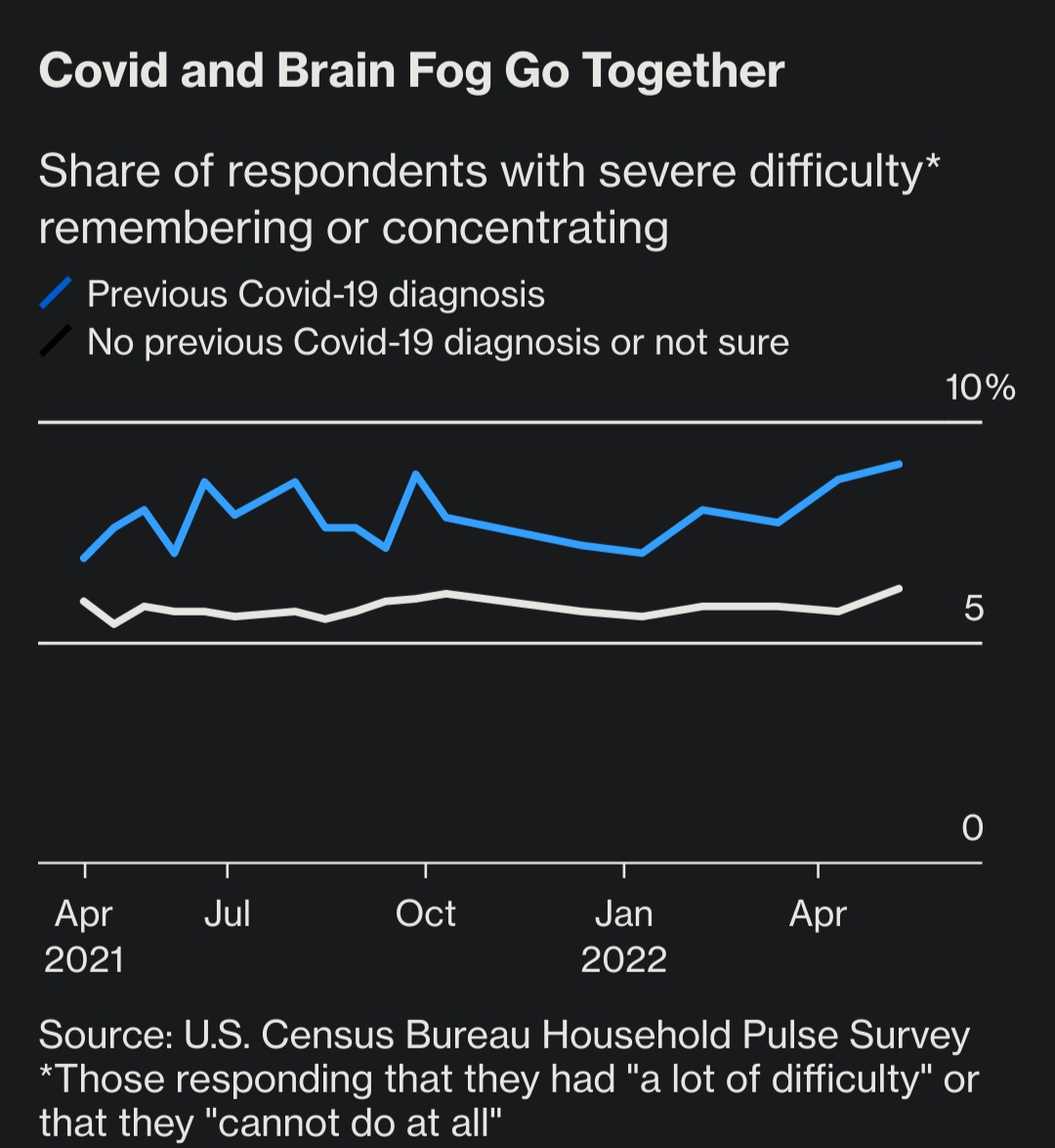

- COVID may lead to brain damage (large biobank study), although maybe cognitive performance is preserved[10]

- There are more effects, such as lowered testosterone in men. I expect we will find more long-term health effects over time, especially as infections accumulate

Economic effects

- High rates of disability contribute to labour shortage, which has wide-ranging economic effects.

- People living in poverty/hand-to-mouth will be very hard hit[11]

- Burden on care systems (doctors & caretakers), caused by increased disease and mortality + disabled/burned-out healthcare workers → lower quality of care → more loss of healthy life years[12]

- This is also affecting the effective altruism labour pool

Susceptibility to pandemics (speculative)

- Reduced immune function could lead to more susceptibility to other infectious diseases

- This could be a contributor to the monkeypox outbreak

- This would be a massive risk factor for biorisk, if true

Decision-making & reduced cognition

- The fact that COVID can cause lasting brain damage and cognitive issues on a large scale should be very concerning

- Effects are hard to quantify/identify, but it's a factor affecting any cause you care about

- Examples of consequences: worse decisions by those in power, reduced impulse control, worse communication, reduced research quality

Tail risks

- Given the high uncertainty around prevalence there's a non-negligible probability that already a lot more than 2% of the population has Long Covid. If so, continued reinfection would lead to even larger societal disruption

- Long-term complications from 'asymptomatic Long Covid' can be more severe than foreseen

Outside view

"This sounds dire, but also unprecedented. Surely we would have seen this in previous pandemics? Otherwise, what's unique about the current pandemic?"

- I think similar disability happened after other pandemics like the 1918 Spanish flu, but it was largely ignored

- See e.g. the 1919 famine in Tanzania, which was caused by workers being too exhausted to work the field (+ supposedly a fraction of the working population having died)

- Without modern communication, the current patient community would not have been able to raise the alarm

- There seems to be a cultural phenomenon of 'pandemic forgetting'

- SARS-CoV-2 seems relatively effective at causing long-term disease

- Modern interconnectedness and scale giving unprecedented rate of mutations and reinfections

Tractability

This section only relates to 'symptomatic Long Covid'. Also: I have no biomedical background.

The Viral Persistence Hypothesis is the idea that some SARS-CoV-2 infections are not fully cleared. Instead, (small) amounts of virus may persist in patient tissue by evading the immune system. There, it can provoke ongoing inflammation, aberrant immune responses, affect host metabolism, and consequently damage the patient's body and interfere with normal functioning. Locations of persistence are called viral reservoirs.

Occam's Razor: viral persistence is one of the simplest explanations.

There is plenty of evidence of other RNA viruses persisting in many different ways. Traditional virology accepts that many RNA viruses can persist, also in immunocompetent humans. However, it is very understudied, especially in how it relates to particular chronic diseases. Most virologists and MDs are not aware of the latest research in this area.

Standard approaches to diagnose infection are not sufficient to exclude viral persistence:

- Antibodies not reliable

- PCR for viral protein in blood/other fluids/feces; easiest place to remove by immune system

- Expectation: in tissue → biopsies are gold standard

Evidence is strongly suggestive of viral persistence:

- Circulating full spike was found in 20/31 (60%) Long Covid patients' blood with novel technique, and 0/26 controls

- Have to be produced in some reservoir; very unlikely to be preserved 'leftovers' from acute phase

- Sniffer dogs trained on acute COVID identified sweat samples of 23/45 (51%) Long Covid patients, and 0/180 healthy controls. Follow-up with better samples identified 13/14 (93%) patients with Long Covid

- Not clear what exactly the dogs are detecting: are the volatile organic compounds viral particles or something else unique to COVID infection?

- Successful virus isolation confirmed up to 128 days post infection in immunocompetent and PCR-positive cases.

- Complete SARS-CoV-2 genome integrity was demonstrated, suggesting the presence of replication-competent viruses.

- Promising anecdotes of people trying short courses of antivirals[13]

- Antivirals have very specific mechanisms, so highly likely the benefits are due to temporary viral suppression

- Long Covid patients exhibit much more active SARS-COV-2 specific T-cells

- Immune system is still recognizing infected cells and trying to clear them

- Larger overview of viral persistence-related papers here

Alternative hypotheses for root cause(s)

A number of disease processes have been found. In theory, these could by themselves account for ongoing symptoms. However, it seems more likely that they are downstream consequences of viral persistence.[14]

- Autoimmunity triggered during acute infection

- Autoimmune markers have been found (e.g. auto antibodies)

- Fits traditional autoimmunity paradigm that immune system can be "triggered" into self-harming equilibria by viruses[15], including SARS-COV-2

- Alternatively, autoimmunity is the side effect of the immune system targeting ongoing pathogen activity but being unable to resolve it (via e.g. 'molecular mimicry' or 'bystander activation')

- Self-sustaining inflammatory cascade

- Inflammation is both a repair and destroy function.

- Could theoretically self sustain

- Self-sustaining clotting cascade

- Microscopic blood clots have been found in most cases

- Could theoretically self sustain

- More likely to be driven by spike protein

- Reactivated pathogen(s)

- E.g. landmark paper showed 1 in 3 patients who developed Long Covid had reactivation of Epstein-Barr Virus during the acute phase

- Reactivated pathogens could drive disease even after SARS-COV-2 clearance

Postvax anomaly

- Some people present with identical symptoms to Long Covid immediately after vaccination[16], and subset of these are allegedly never infected

- Potentially conflicts with viral persistence hypothesis: if same symptoms can be caused by vaccines, viral persistence isn't necessary

- However, it's hard to rule out prior infection. Perhaps there is viral persistence, and a vaccine induces a stronger (but not sufficient) immune response, leading to symptoms

- Also possible for two different mechanisms to cause same symptoms

Viral persistence offers clear targets for symptom resolution

- If Long Covid is often caused by viral persistence in tissues, the logical solution is to aim for viral clearance or permanent viral suppression.

- Case studies exist of patients with Long Covid and other infection-associated chronic diseases in which all symptoms disappear after successful antiviral therapy. Nonetheless, it remains a possibility that there is organ damage irreversible by antiviral therapy.

- Viral clearance/suppression can be achieved with the right combination of antivirals (including monoclonal antibodies) and immonusupportive drugs.

- Many of these drugs are already being developed, researched, and approved for acute COVID.

- Besides discovering effective treatment, deploying accurate diagnostics and achieving worldwide accessibility to treatment will still be challenges.

Secondary effects of addressing Long Covid

Long Covid research may

- Accelerate a paradigm shift towards the role of chronic infections in a wide range of diseases

- Create scientific opportunities in other fields by using new methods and technologies

And it may have specific positive spillover effects on

- Other diseases that are linked to chronic infections, such as ME/CFS, Lyme, and MS

- More speculatively: Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and (other) autoimmune diseases

- Pandemic response therapeutics (e.g. immunomodulating therapeutics, antiviral combinations)

- All virally-mediated diseases

Urgency

- Earlier treatment likely more effective

- Earlier treatment less disruptive to lives and society than long-term illness

Crowdedness

- Current treatments are largely ineffective or even harmful, relying often on 'reconditiniong'

- NIH is biggest funder ($1.15B), but not able to distribute it fast, effectively, and flexibly (see e.g. criticism in The Atlantic[17])

- Other countries have smaller budgets, and not allocating much to promising treatments (none to antivirals)

- Lots of research groups working on acute COVID, SARS-COV-2, and a decent amount on Long Covid with (presumably) pre-existing budgets

- Balvi/Vitalik Buterin: funded $6M to Patient-Led Research Collaborative + $1.4M to gut biopsy study by PolyBio/Mt. Sinai

- Institutional biases:

- Acknowledging Long Covid in conflict with "let it rip" policy of many governments and current social norms

- ME/CFS is the most underfunded disease in relation to disease burden

- ME/CFS has a long history of being dismissed as 'psychosomatic'

- If current growth rates continue, hard to imagine governments not starting to fund significant amounts within a year or three

- Will depend on which infrastructure exists then, whether that funding is used effectively

- Personal impression: absent 'intervention', current time to a treatment with 50% efficacy (relieving 90% of a patient's health burden) seems like >10 (70% confidence: 5-25) years.

- The field lacks coordination, speed, and a vehicle for pharmaceutical companies to collaborate

Conclusion

- I'm really very concerned

- Tentatively, I want to say that symptomatic + asymptomatic Long Covid is comparable in scale/societal disruption to climate change

- But developing faster

- And more tractable to solve (especially symptomatic Long Covid)

- Next month, I will share more about the organisation I'm helping, when they launch publicly.

- They have $50-100 million room for funding that can be rapidly deployed usefully

Policy implications

- Often mentioned by other organisations regarding covid prevention/mitigation:

- healthy indoor air: HEPA, CO2 monitoring, UVC ceiling lights

- masking indoors/certain public spaces like hospitals, pharmacies, supermarkets

- High value to zero COVID via next generation vaccines (e.g. nasal, T-cell) in addition to above non-pharmaceutical interventions

- High value of information for more robust cause area research and exploratory grants

- Including the speculative risks of cognitive decline and immune damage

- Value in protecting the EA labour pool by increasing the air safety of physical EA spaces

- Research into treatments is very urgent and likely very cost-effective

- Large scale diagnosis should be urgently pursued

- Large scale treatment will be a later bottleneck

Possible actions people can take individually

- If any potential funders are convinced Long Covid is worth funding, you can contact me at sieberozendal@gmail.com

- Do cause area research.[18] I’m happy to assist in the capacity of ‘expert to be consulted’ rather than ‘research mentor’

- Figure out biggest obstacles in COVID mitigation/prevention and address them

- Found a charity to roll out valid diagnostics

- Make EA spaces safer[19]

- Follow me for tweets about (Long) COVID on Twitter[20]

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Justis Mills, the team of the organisation I'm working with, and especially Anne Ore for feedback on earlier versions of this document.

Footnotes

- ^

I'm excluding China in this extrapolation due to much fewer acute COVID infections there.

- ^

Unfortunately, none of these studies included the ME/CFS hallmark feature of Post-Exertional Malaise (disproportionate exhaustion/symptom flares after exertion), nor a diagnosis of orthostatic intolerance/POTS (difficulty tolerating upright posture).

- ^

I refer to multiple USDVA studies, but there is criticism that this dataset has heavy selection bias. E.g. more severe cases are more likely to get a test for COVID, dataset is skewed male while Long Covid skews female, and they use antibodies to determine prior infection (inaccurate)

- ^

- ^

It’s not clear to me how this number compares to their control group.

- ^

Disability rates are higher in the working population.

- ^

See tab 'Implied Recovery Rate'. This is one reason why I believe self reports are more likely to lead to underestimates than overestimates; people seem to initially not recognise their symptoms as Long Covid, especially in the case of parents reporting on their children's health.

- ^

They are very similar to UK numbers, but were more accessible

- ^

Number based on vague recall of PCR sensitivity/specifity.

- ^

There are concerns that the neuropsychological testing used in this study was inadequate to pick up the specific deficits

- ^

For example, see the 1919 post-pandemic famine in Tanzania; workers were too few and too disabled to harvest the full yield.

- ^

There are already hospitals in Western countries unable to take emergency cases during the BA.5 peak, let alone planned treatments: e.g. UK, and Dutch hospital closing emergency department 3 days/week (citing sick leaves & inability to hire). In the UK, there are serious excess deaths among all age groups that are thought to be the result of delayed/lower quality care + long-term effects of COVID.

- ^

Effective antiviral therapy is often much longer (>8 weeks), uses multiple antivirals to prevent antiviral resistance, ideally includes an immunosupportive drug, and requires clinical monitoring of progress and side effects.

- ^

Here's a great talk by Amy Proal, ME/CFS and Long Covid researcher, and one of the primary proponents of the Viral Persistence Hypothesis.

- ^

The current mainstream view of autoimmunity holds that a time-limited trigger or genetic defect causes the immune system to attack host cells. Long Covid is associated with autoimmune markers. If Long Covid is a chronic infection, this lends evidence to an alternative paradigm; that autoimmunity is the result of the immune system trying and failing to eradicate an ongoing trigger, such as an infection. Recently the 'autoimmune disease' MS has been linked to chronic Epstein-Barr Virus infection.

- ^

I've met plenty of post-vaccine patients online. They are never anti-vaxxers, and I believe them fully.

- ^

The Atlantic has the best Long Covid coverage

- ^

Some high-level research considerations here

- ^

I personally like Corsi-Rosenthal Boxes: cheap DIY HEPA filters that are equal to/more effective than commercial devices. But there are many alternatives with lower time cost.

- ^

Deepti Gurdasani also has very insightful threads.

I'm sorry you are suffering with long covid Siebe. I'm personally more sceptical of the size of the effects of long covid.

One argument is a sense check - if the effects were this big, we would expect many celebrities and footballers to have retired with long covid, but I know of no such cases having looked for some time. The BBC has an article on a footballer who retired with long covid, but he wasn't a pro footballer at the time he retired.

There's also this paper which sheds some light on the overall background rate of long covid symptoms - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2787741

We've gotten a bit into the weeds in the other comments, and in this one I'd like to zoom out a bit to see what argument you're actually making. I'll make an attempt to (re)construct your argument, and you can tell me where I'm misrepresenting it.

I've already argued against 2 with the Airtable containing >100 athlete sudden deaths/collapses + a few news articles of arguably below-top-level.

[Jan 2023 EDIT : I don't think this Airtable is strong data anymore, but very weak]

Re: 1.

I do think that it should be taken into account that the information ecosystem around COVID and Long Covid is really, really bad. Patients typically get misdiagnosed a lot before biological abnormalities are found, public health authorities spread a lot of misinformation, and most media outlets have pretty bad coverage. In this ecosystem, I don't think it's easy to spot athlete retirements due to confirmed Long Covid, or any other signals.

Re: 3

More importantly, I'm of the opinion that the evidence I offer in the post is of sufficiently higher quality than a google search for news reports: i.e. cohorts with controls, population samples, disability data, and biological data (e.g. seems like at least 50% of LC patients have COVID-specific markers). In my opinion, if you want to assert that the main claim in the report is wrong, you have to additionally argue that at least one of the following is wrong (If not, I think you're only justified to claim 'something here doesn't make sense, but it's not clear what').

A. The controlled cohort studies & disability data is wrong

B. The controlled cohort studies & disability data are do not justify the high amounts in the UK population sample

C. The population sample is right, but professional athletes have significantly lower rates of Long Covid

D. The numbers are right, but a signifcant fraction are not attributable to COVID, but something else

E. Something else, or a combination of weaker versions of the above claims

I agree with you that C is unlikely.

Also, the rate would need to be substantially lower for my claim that 'this is a major problem' to be invalid (although you're not explicitly claiming it's invalid). E.g. at 60million/year, it's still enormous. At 30million, arguably still big.

I had a quick look at the Airtable. Many of the people included do not seem to be professional athletes at the time that they died/collapsed. For example, this includes an ice hockey player at a university, someone who plays basketball in the fourth tier of the Spanish league and a former pro runner. This expands the sample so much as to make inference from the data impossible. There is a reason to focus on professional footballers in England because we know the sample size, there are a lot of them (5,000) and we should expect news about long covid-induced retirement to make it into the news.

By your estimates, 0.25% of people in the whole UK population are impaired a lot by long covid. We should therefore expect 13 of the 5,000 English pro footballers to have retired or gone on the news saying they can't play because of long covid. I have looked into this and know of no cases of this. I know other people have looked into this after I offered them a bet and also haven't found any.

I think the studies of long covid are wrong and that the controls are not good. The symptoms of long covid are vague, highly variable in severity, and already widely prevalent in the population (in the integers of percent).

Thanks for the clarity John!

It's actually higher than 0.25%. More like 1 in 5 out of ~1.8% (avg. prevalence among 17-34, with shootings >3 months), so 0.36%.

Some of those will be recent though, so those we shouldn't expect to be reported in the news even if the news was taking everyone. 30%?

Some will retire not knowing it's actually Long Covid and state other reasons. 50%?

That leaves like 6 people, which to me is sufficiently small that it can be missed by chance (eg. no top level players have gotten severe Long Covid).

I'm also wondering if heart failure is another outcome rather than Long Covid and disability. ME/CFS is a really strange disease where people can push through a lot, and only get the bill later. It's not that people literally can't run.

Regarding the studies: I agree that there's a lot to be desired regarding symptom measurement (I think we'll see better measurement in the future). But even the vague symptom descriptions are significantly higher in PCR-confirmed covid cases, so I don't understand your worry.

I went through the Airtable more systematically and found 7 English football players that had heart issues/collapsed on the field in 2021/2022. None were explicitly linked to covid, but only 1 had rumours of an underlying condition. 2 out of 7 players were in League 7 though. I think it's still pro, not sure.

Analysis here.

Hi John,

I've considered checking samples of public figures, but dismissed it because it's really hard to get a good sense of who has Long Covid:

I'm not sure how much top performance is affected in mild cases. I think in early stages it's possible to push through a lot. The main symptom is fatigue post exertion. We would still expect to observe reduced performance though, but that's harder to observe.

Retirement is a drastic decision and people would generally postpone that.

Due to these issues, I feel like disability data is a much more reliable sense check, and I think it fits the ONS UK numbers.

The article you link to isn't good, because they probably had a lot of Long Covid cases in their control group. They used antibodies as sole diagnostic criterion of prior infection. But about 1 in 3 people do not create detectable amounts of antibodies (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/27/9/21-1042_article), antibodies fade over time, and there's some rumors that Long Covid patients are now likely to not have antibodies but I haven't checked that. The fact that there's no easily accessible diagnostic tool makes it hard for all these prevalence studies.

On the study, even if the antibody test isn't that accurate, one would still expect people with confirmed covid to have more long covid symptoms than people without confirmed covid. In fact, the study finds that belief in having had covid is a stronger predictor than confirmed covid, which suggests that the symptoms are caused by something else.

But people who have had COVID do have more Long Covid, if actually use an accurate measure (PCR testing). I report multiple studies in the post with control groups.

In the study, people with positive serology HAD more of 10 specific symptoms, even though serology is very inaccurate. Only when controlled for belief did that disappear. But belief in having had COVID has strong confounding effects:

If you control a weak predictor by a strong predictor correlated with the weak predictor, I'm not surprised that significant effects disappear.

The study also had data on PCR testing but didn't use that in any way, which seems suspicious to me.

Also, in 2020 the base rate for other communicable diseases dropped a lot (flu dropped by factor 50x)

The problem with PCR test controls is that they would only catch an infection around the time you get infected, whereas antibody tests would catch infections further back in time.

I don't see the evidence that belief in having had covid is a better predictor of having had covid than is a serology test.

And here's an Economist article analysing footballer performance after COVID infection: https://archive.ph/qGWKs

Average performance measures definitely dropped significantly long-term. But it doesn't have data on all-out disability.

And this article lists a few names, but also mentions what you write: that surprisingly few athletes had Long Covid at the time of writing: https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2021/04/19/athletes-long-haul-covid-justin-foster/

On the economist article, the study didn't find a significant drop, it found a reduction in minutes played of 2 minutes per game and a reduction in passes of 3 per 90 minutes 225 days post-covid. Although zero effect is outside of the confidence interval for the passes metric (but not minutes played) according to the study, the effect is so small, and the measure so noisy, that in my view it is almost certainly a statistical artefact.

Fair enough re: significance and effect size. I don't think it's an artefact though

Regarding public samples, I had been thinking of a political body like a parliament, but as this Senator with Long Covid says: many people are not public about their disability. https://twitter.com/wsbgnl/status/1505814009722798081?s=20&t=iLBZn1qk_BUJQcJx8kIQEg

(Not clear from the quote whether he refers to other senators, or colleagues in different positions)

I agree the number of soccer players reported to be out of play due to Long Covid is low enough so we can be confident that Long Covid risk for healthy young demographics is <<2%. I'm not sure it's low enough to be confident it's <0.5%.* I think "0.5% Long Covid risk for young people; higher for older people" would just about make it into the lower end of Siebe's 70% confidence interval of people who are suffering from Long Covid. (To get to the higher end of the confidence interval, we'd have to assume that the vast majority of people who get Long Covid are from older demographics and presumably had severe disease – and maybe vaccinations have brought these risks down a bunch, so I'm skeptical about the higher parts of the range in the confidence interval.)

*Professional athletes are probably trying to avoid getting Covid. After 5 minutes of googling, I could find a bunch of accounts of soccer players with Long Covid. Arguably, there are fewer than 200 "world-famous soccer players" currently active, so not seeing a case in the news of a famous player who was forced to retire isn't strong evidence against a Long Covid incidence of 0.5%.

Here's the long Covid prevalence per age group per the ONS UK data, per May 1st 2022

2 to 11 0.45%

12 to 16 1.44%

17 to 24 1.50%

25 to 34 2.14%

35 to 49 3.23%

50 to 69 3.10%

70+ 1.53%

Average 2.21%

I don't think pro athletes are any less likely to get covid than other people. The English football leagues continued throughout the early peaks of covid and (anecdotally) vaccine scepticism rates among footballers seem to be surprisingly high.

If any English footballer retired due to long covid, it would be national news. The premier league is by far the most popular sports league in the world and if any player retired due to long covid it would be huge news. The second tier of English football has the third highest attendances of any league in Europe; numerous clubs gets tens of thousands of fans at each game. The only case of news reporting on a footballer retiring with long covid was a BBC report report on one non-famous squad player for AFC Wimbledon (a fourth tier club with few fans) who retired because of long covid. But he had been released from his pro contract before getting covid and so wasn't actually a pro footballer. There are about 5,000 pro footballers in England and there are no other news stories about players retiring with long covid after 1.5 years of covid. This suggests that the risk to healthy young people is low.

There are reports in the news of players suffering with long covid, where this is struggling with recovery a couple of months after getting covid, but all of those people have subsequently started playing again.

don't really get why this has been downvoted so much. The BBC reported on a non-famous non-pro footballer player who claimed to retire due to long covid, which is evidence that the media would report on one of the 5,000 other pro footballers if they were to retire due to long covid

(wasn't me!)

Okay so a person on the org's team sent me the following:

He also sent these news articles:

Sergio Agüero quit (striker Barca): https://www.sportingnews.com/us/amp/soccer/news/sergio-aguero-retired-heart-doesnt-work-man-city-barcelona/o6ikz9xb9h466zxdtzbdagg6

Scottish #1 female tennis player (supposedly recovered after 18 months): https://news.stv.tv/sport/scottish-number-one-tennis-player-maia-lumsden-feared-career-was-over-after-long-covid-diagnosis

2 British female tennis players (don't know their rank) 1 supposedly recovered after 18 months, 1 bedbound: https://www.skysports.com/tennis/news/12110/12577541/british-tennis-duo-maia-lumsden-and-tanysha-dissanayake-fear-for-careers-due-to-long-covid

A lot of these aren't directly getting attributed to COVID, but it's highly suspicious to have medically unexplained symptoms during a pandemic. Personally, I feel like this passes your sense check ;)

On Aguero (one of the greatest strikers of all time), he retired with cardiac arrhythmia.

This article quotes his doctor: "But Roberto Peidro, who has treated Aguero since 2004, says it has “nothing to do with Covid or the Covid vaccine”.

There are cases of footballers/athletes retiring/dying with heart problems or suffering from severe heart problems every few years. The examples of Cristian Erikson, Fabrice Muamba, and Marc Vivian Foe spring to mind from memory. There is also James Taylor, the cricketer.

That's a useful article. Makes it much less likely to be COVID related, because there's a plausible alternative explanation (but his doctor could be wrong. Doctors have been wrong about Long Covid a lot).

I found the Air table list surprisingly big, and would love to see a year by year comparison.

Very sorry to hear you have long covid, I hope you feel better soon.

I'm personally unconvinced that this is a neglected area.

Over $1bn is committed to researching this, with public and private initiatives planned. https://www.science.org/content/article/new-private-venture-tackles-riddle-long-covid-and-aims-test-treatments-quickly

And as you point out, there is a large market of consumers who need this in wealthy countries, which should mean normal market incentives to develop drugs apply.

Hey, thanks for the engagement.

The 1bn is not being spent very well by the NIH. A lot of it went to organisations without the necessary infrastructure or expertise. They're not conducting the necessary research to determine viral persistence.

The planned trials by the NIH are not very exciting, and are going slow.

The "private venture" is the organisation I'm affiliated with. It has a funding gap of ~80 million at the moment and is primarily funding constrained. I'll write more about LCRI in a new post soon :)

Thank you for a great and detailed summary of the issue Siebe!

As recent developments seem like quite a major improvement (even if at least temporarily)- for the Nov 22 update to new cases, are any major causes emerging yet for the increase in less than one year recoveries and reduction in severe LC cases? And when over the next few years would you expect the numbers to grow significantly, as a rough estimate?

Less positively, I really agree about the potential for cognitive decline via asymptomatic LC to impact decision-making of those in power. If most people, including those in power, get Covid and even mild cases might cause a small intelligence drop, if enough potentially hazardous situations happen, even this small decline could be enough to tip the balance in an international crisis. Even if this might be bad and not disastrous in some arenas and some mistakes can be corrected, perhaps just one miscalculation is most worrying for potential nuclear diplomacy/crises? (E.g. if Stanislav Petrov helped to save the world from an accidental nuclear war by quickly reaching the conclusions that a system malfunction was more likely than a small enemy nuclear first-strike, might a future 'mild/moderate brain fog Petrov' not interpret any unexpected information quite so well?)

On treatment, do you have any opinion on Low Dose Naltrexone, which many ME/CFS sufferers have found beneficial and, according to at least some very preliminary evidence, might be useful for LC? And as a final question, though I don't doubt there's a significant drop, do you also know if there are any good studies on the average happiness/life satisfaction loss of LC sufferers?

Either way, I hope you're feeling as good as possible with your LC experience (from someone with previous/managed experience of ME/CFS) and thanks again for a great post.

"are any major causes emerging yet for the increase in less than one year recoveries and reduction in severe LC cases?" Not sure if I understand your question, but: it looks like people who got LC from a reinfection were getting assigned as if they had LC since their first infection, which messed up the recovery data.

I still don't know why new cases are less likely and less severe, probably a combination of: fewer susceptible people, significant protection from vaccines and previous infection, and a longer time since certain viruses were prevalent that led to an imprinted response. That is, the immune systems of people who develop Long Covid seem to often have responded by making antibodies against other coronaviruses rather than making entirely new and specific antibodies.

And when over the next few years would you expect the numbers to grow significantly, as a rough estimate? 6-12 months maybe? I don't know. Vaccinations are dropping in Western countries. I don't think we'll see a similar growth rate as we saw on the

LDN: funding for a trial just got announced. It won't be a game changer, but seems like it helps some people somewhat (and a lucky few benefit a lot)

Life satisfaction: not aware of great studies. It's pretty bad, though maybe not as bad as ME/CFS. I'm especially worried about people in low income countries, which we hear next to nothing about

Siebe, thanks for this, and sorry to hear you're suffering from long COVID! Would you be open to posting a link to this on LessWrong? I think the analysis would be of personal interest to many there, independent of its merits as a cause area.

I'll post it there in a bit then!

Hi Siebe, I like your post and agree largely with your conclusions.

Currently I'm wondering if there are any studies being done that can adjust our knowledge about the probabilities of extreme tail risk events (e.g., covid causes SSPE-like illness in a substantial fraction of people, or that it contributes significantly to cancer risk like HPV, or...), and if long-covid researchers are keeping an eye out for these probabilities.

Hopefully, it'll be easier for decision makers to spot tail risk events, but I'm not confident about this.

I don't know about SSPE.

There have been some studies but I haven't looked into it. There's some using the VA dataset but I don't trust the quality of that. Cardiovascular risk seems more likely than cancer risk.

There's some speculation that a subset of people might develop AIDS, because SARS-CoV-2 can infect CD4 cells just like HIV and some patients seem to have really low lymphocytes counts, but probabilities are hard to estimate.

There's increasing evidence that song healthy convalescents harbor persistent SARS-CoV-2:https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11695-022-06338-9. I think this will come out to 15-30% of the population, but there's a small probability that it's >90% once we start looking closely.

The only thing I see anyone talking about the comparison between SSPE and long-covid is this popular-level article from Peter Doherty, and he seems to be unaware of any evidences suggesting whether it's likely or not (only, "hopefully unlikely").

https://www.doherty.edu.au/news-events/setting-it-straight/issue-114-persistence-of-sars-cov-2-and-long-covid-2-defective-virus-privil

I used to believe that pandemics in themselves are not enough to be an extinction level event. Now I'm not quite sure...IF something attains the prevalency of Covid but leads to serious illness with a high mortality rate (eg. SSPE) in a large proportion of people (instead of the measles/SSPE relationship) several years down the line, the result is going to be catastropic (and I don't see why there will be any evolutionary pressure that prevents a virus from behaving like this).

On the other hand, some animal species seem to have handled their equivalent of HIVs...https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0700471104

Information about viral persistence has been on the popular press for a while, but it didn't impact the public perception of covid (at least, not enough to affect the trajectory of our pandemic policies).

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-26/coronavirus-can-persist-for-months-after-traversing-entire-body

I wonder if there are more follow-up autopsy studies on covid persistence (that would allow us to look really closely, and in all the organs including the brain). The logical next step is to check if the presence of persistent covid is different in people who recovered from covid, compared to those who died during hospitalisation.

I think it is justifiable to make "testing for presence of persistent covid virus" a standard procedure for all autopsies. It'll make autopsies more expensive and resource consuming but I think it would likely still be a negligible proportion of societal resources...and might give us a quick answer on long covid and its associated risks (eg: it would sound like big trouble if ~80% of healthy people who died from drowning/vehicle accidents/homicide had viable covid reservoirs in their major organs...)

Of course, that requires a lot of influences on the policy makers. But maybe current long-covid research groups can do some follow up autopsy studies? That might be a start as well, at least in gauging how bad the situation can be.