Max Roser has a recent post arguing that progress against extreme poverty is likely to stall after 2030, with the number of extremely poor people projected to increase as stagnant economies in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) fail to keep pace with population growth.

This conclusion depends heavily on the accuracy of current population baselines and UN demographic projections. For several key countries, particularly those with weak statistical infrastructure and infrequent census data, both may be substantially overstated.

Population baselines may be inflated

Nigeria’s official population figures have long been contested. The country’s last census was conducted in 2006, and subsequent population estimates have been based on extrapolations rather than actual counts, with researchers using satellite imagery and geographical information systems suggesting the last census considerably overstated Nigeria’s urban population and that current population may be closer to 170-180 million rather than the official 220-230 million.

Similar issues could affect DRC and Ethiopia.

- DRC has not had a census since 1987

- Ethiopia’s official statistical service estimated the population at 109 million in 2024, substantially lower than the 132 million cited by the World Bank

These aren’t minor discrepancies. Nigeria alone could account for a significant share of SSA’s projected poverty increase. If its population is overstated by 50 million and roughly 40% live below the international poverty line, that’s ~20 million fewer people in extreme poverty than current figures suggest. Extending similar corrections across other countries with poor statistical capacity could materially lower the global baseline.

GDP per capita calculations depend on accurate denominators

Inflated population figures distort poverty measurement in two ways.

- First, they overstate the number of people in poverty

- Second, they understate GDP per capita, making economies appear more stagnant than they are

If Nigeria’s actual population is 175 million rather than 230 million, the same total GDP divided by fewer people means per capita income is roughly 30% higher than official figures suggest.

A country with 2% GDP growth and 3% population growth looks like it’s getting poorer, but if actual population growth is 1.5%, it’s achieving modest per capita gains.

Fertility is declining faster than UN projections assume

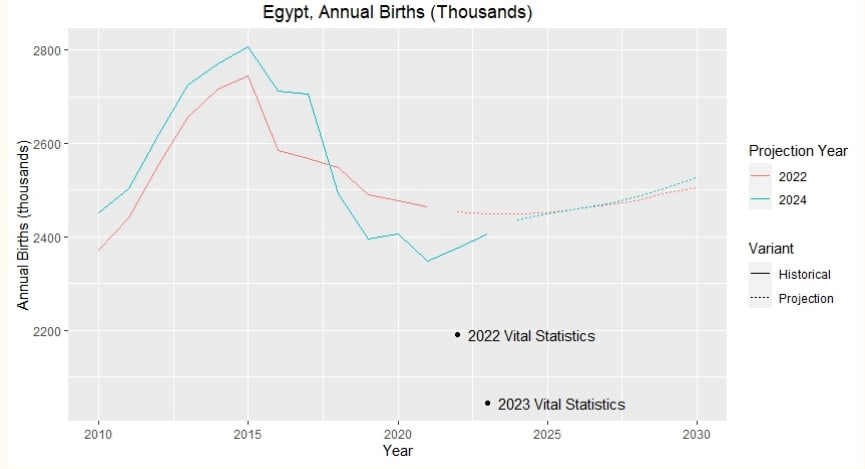

Recent analysis by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde highlights significant discrepancies between national vital statistics and UN estimates. For Colombia, Türkiye and Egypt, actual 2022-2023 birth counts from national registries fall substantially below what UN projections anticipated.

Recent projections suggest fertility may be declining faster than anticipated, with Nigeria’s total fertility rate falling to 4.6 in 2021 from 5.8 in 2016, a 20% drop.

This has led to repeated downward revisions, the 2024 UN World Population Prospects report lowered Nigeria’s 2100 projection to 477 million, down from 914 million in the 2012 report.

Fernández-Villaverde estimates that correcting for these discrepancies suggests the world’s total fertility rate in 2024 is likely around 2.17 rather than the UN’s 2.25 estimate, meaning humanity may have already fallen below the global replacement rate of 2.21 (higher than the typical 2.1 when taking into account child mortality rates globally).

Urbanisation

The fertility decline accelerates through urbanisation. Women in urban areas of Sub-Saharan Africa typically have fewer children than those in rural areas. As the proportion of people who live in urban areas is projected to increase, this compositional shift will drive fertility down faster than national-level projections suggest. This effect is compounded if more population overcounting has occurred in rural areas (although without accurate census data it’s difficult to determine where overcounting has happened or if it has happened at all).

As well as lower fertility, urban areas have higher average incomes. The combination of faster urbanisation than expected and lower urban fertility means poverty should decline faster than current projections indicate.

What this means

Our World In Data looks at projections that assume 2015-2024 growth trends continue, using UN demographic forecasts as the baseline. If those inputs overstate current populations, rural composition and future growth rates, the projections will be systematically pessimistic.

This doesn’t mean these countries are doing well or that stagnation isn’t a serious problem. It means the specific claim that progress will reverse after 2030 rests on demographic assumptions that may be materially wrong in a potentially consistent direction.

If actual populations are lower and growing more slowly than official figures suggest, several things follow.

- Current extreme poverty headcounts are overstated

- GDP per capita growth has been understated (making recent performance look worse than reality)

- Future poverty trajectories may be less pessimistic than current projections indicate

The case for urgency in addressing economic stagnation in the poorest countries remains. But the timeline and magnitude of the challenge may be different than current data suggests. We should be cautious about declaring “the end of progress” based on demographic data that carries substantial uncertainty, particularly when that uncertainty is potentially directionally biased.

Better census data and population indicators in these countries would reduce the uncertainty. Until then, projections should be interpreted with appropriate scepticism.

Thank you for posting this!

Thank you for the insightful post about calibration about the future demographical situation of the world.