This is a summary. The full CEARCH report can be found here.

Key points

- Policy advocacy, targeted at a few key countries, is the most promising way to increase resilience to global agricultural crises. Advocacy should focus on increasing the degree to which governments respond with effective food distribution measures, continued trade, and adaptations to the agricultural sector.

- We estimate that an advocacy campaign costing ~$1million would avert 6,000 deaths in expectation. Incorporating the full mortality, morbidity and economic effects, the intervention would provide a marginal expected value of 24,000 DALYs per $100,000. This is around 30x the cost-effectiveness of a typical GiveWell-recommended charity.

- Compared to other interventions addressing Global Catastrophic Risk (GCR), the evidence is unusually robust:

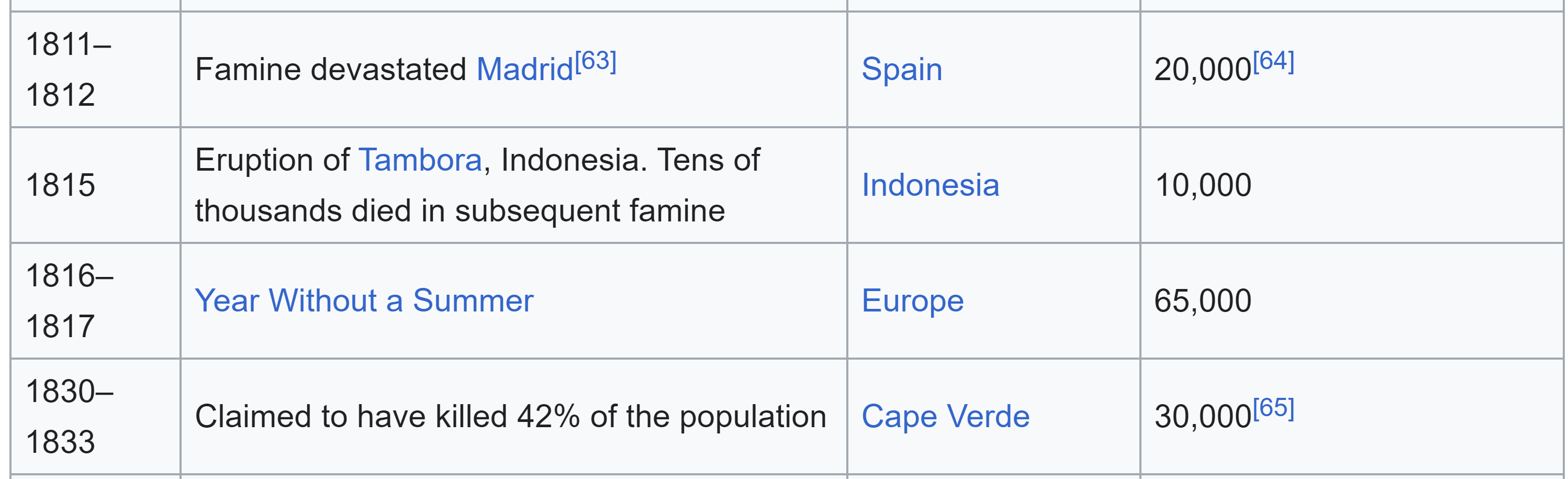

- We know that the threat is real: volcanic cooling is confirmed by the historical and geological record.

- We know this is neglected: current food resilience policy focuses on protecting farmers and consumers from price changes, regional agricultural shortfalls or from small global shocks. There is very little being done to prepare for a significant global agricultural shortfall.

- We are uncertain about the effect size: we have significant uncertainty about the extent to which governments and the international community would step up to the challenge of a global agricultural shortfall. There is little evidence on the scale of the effect that a policy breakthrough would have on the human response.

- GCR policy experts were broadly optimistic about the value of further work in this area. On average, they estimated that a two-person, five-year advocacy effort would have a 25% probability of triggering a significant policy breakthrough in one country. Experts emphasized the importance of multi-year funding to enable policy advocates to build strategic relationships. Some experts suggested that food resilience is a better framing than ASRS (cooling catastrophe) resilience for policies that protect against global agricultural shortfall.

- We identify two main sources of downside risk. (1) Increasing resilience to nuclear winter could reduce countries’ reluctance to use nuclear weapons. (2) nuclear winter resilience efforts could be seen by other nuclear-armed states as preparation for war, thereby increasing tensions. However, these risks are unlikely to apply to broader food resilience efforts.

Executive Summary

This report addresses Abrupt Sunlight Reduction Scenarios (ASRSs) - catastrophic global cooling events triggered by large volcanic eruptions or nuclear conflicts - and interventions that may increase global resilience to such catastrophes. Cooling catastrophes can severely disrupt agricultural production worldwide, potentially leading to devastating famines. We evaluate the probability of such events, model their expected impacts under various response scenarios, and identify the most promising interventions to increase global resilience.

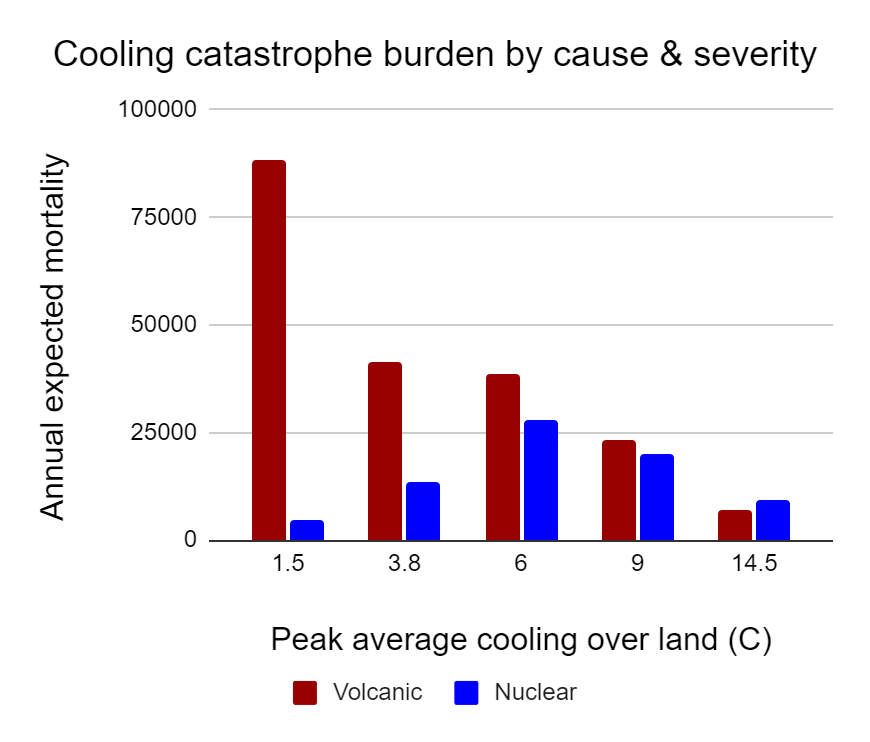

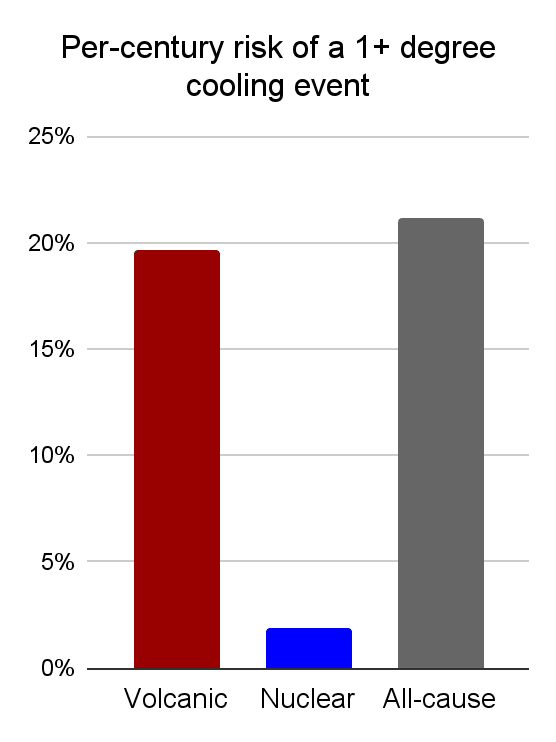

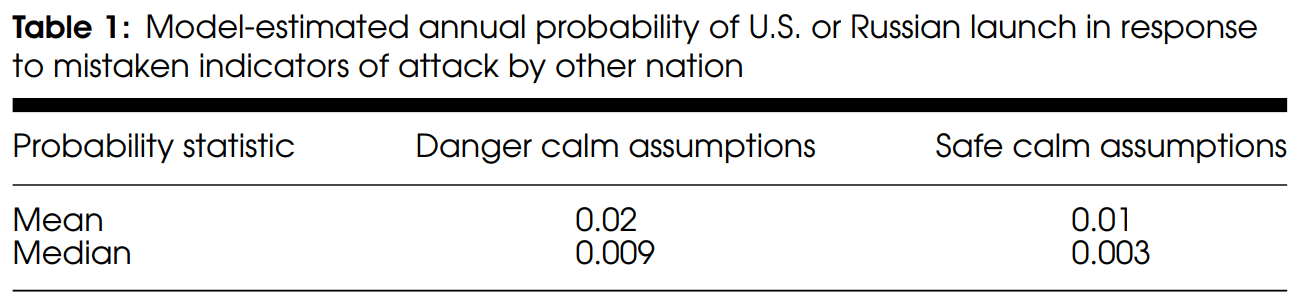

Volcanoes are the main source of risk according to our model, although we expect nuclear cooling events to be more damaging.

We estimate that the annual probability of an ASRS causing at least 1°C of average cooling over land is around 1 in 400, or a 20% per-century risk. Most of the threat comes from large volcanic eruptions injecting sun-blocking particles into the upper atmosphere. While the probability of a severe "nuclear winter" scenario is lower, such an event could potentially comprise a substantial portion of the expected overall burden. This is due to the compounding effects of nuclear conflict undermining the international cooperation and social stability required for an effective humanitarian response.

The annualized burden of cooling catastrophes by scenario. Much of the expected burden comes from mild and moderate cooling scenarios.

Notably, the majority of the projected burden from cooling catastrophes comes from mild and moderate events in the range of 1-4°C cooling over land. We find that in these scenarios, pragmatic policy measures and interventions could significantly decrease the risk of mass famine. Such measures include diverting animal feed towards human consumption, minimizing food waste, and facilitating efficient international agricultural trade and food aid delivery.

A hierarchy of human responses to an ASRS[1].

However, the ability to implement such measures hinges on maintaining public order, economic complexity, and international cooperation - prerequisites that may break down during more extreme cooling events as domestic food shortages increase tensions between nations. To address these risks, we identify policy advocacy aimed at raising awareness and preparedness among governments as the most promising avenue. An investment of around $1 million in advocacy efforts could plausibly catalyze major policy breakthroughs in one or more countries. Potential outcomes include government funding for research into resilient alternative food sources, comprehensive national food security risk assessments, and the development of national response plans for catastrophes that threaten global food supply.

Based on expert surveys and modeling, we estimate that such an advocacy campaign could avert the equivalent of approximately 25,000 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per $100,000 spent in expectation. This figure accounts for the combined mortality, morbidity, and economic impacts projected across a range of cooling scenarios and response effectiveness.

While the report acknowledges that resilient alternative food sources like mass-produced greenhouses or cellular agriculture may prove vital in worst-case scenarios, it cautions that the scaling potential of such solutions is inherently limited without broader resilience measures. On the margin we recommend expanding policy advocacy efforts as a higher-leverage approach to increase the chances of an effective, coordinated government response capable of averting mass famine during the next global cooling catastrophe. We identify a number of organizations that could perform policy advocacy in this space, including ALLFED, which specializes in post-catastrophe food resilience, and Global Shield, which is pushing for GCR policy in the US.

We emphasize that despite the uncertainties involved, investing in food system resilience through pragmatic policy advocacy represents one of the most robust strategies available for addressing the risk from global catastrophes.

Quick links to key sections of the full report

This report was created by the Centre for Exploratory Altruism Research (CEARCH) as part of our cause-prioritization work. We also undertake research commissions.

- ^

The lower stages are high-priority, as they enable conventional agriculture to continue to function. “Adaptation” includes food efficiency measures such as redirecting animal feed to humans, rationing, and reducing waste. To some extent, adaptation would be an inevitable consequence of food scarcity.

Good point.

I looked at WTO agreements early in the research process and eventually decided that WTO advocacy was probably not, on the margin, the best way forward.

Food stockholding

I focused on the consequences of the AoA for food stockpiling (known as "stockholding"), the most urgent concern being that it may dissuade countries from stockholding as much as they otherwise would (as suggested by Adin Richards here). Although food reserves would never be big enough to get us through a full catastrophe, they would buy time for countries to adapt to the cooling shock.

The feedback I got from someone with experience at the WTO since the 1990's was

On the other hand, basic amendment to the AoA seems obviously needed (imho). The original agreement does not properly allow for inflation. It does not make adequate exceptions for very low-income countries (whose market share is so low that allowing them to subsidize farmers would not be very distortionary).

Overall the WTO seems deadlocked at the moment and suffering a crisis of legitimacy. Tit-for-tat between US and China has led to a breakdown of trust in the organization.

If the US was on-side for AoA amendment, it is possible that the other dissenting countries would fall in line. But it is not clear that the US can be influenced on this. The US is doing fine with the system as it currently is, and has other ways of subsidizing domestic agriculture.

Other WTO theories of change

I don't know much about the implications of the AoA beyond stockholding.

The most important things is that we ensure trade continues in a catastrophe, which seems congruent with the AoA. The second most important thing is that countries are able to quickly adapt their food systems in a crisis. In a major catastrophe I think all WTO rules would go out of the window. But could the AoA prevent countries from preparing?

I may well be missing something. Are there other ways the AoA could frustrate resilience work?