Introduction

This post is intended to be read after reading our previous post outlining Shrimp Welfare Project’s 2030 Vision & Absorbency Plans. This post therefore assumes some baseline knowledge of our Humane Slaughter Initiative, which can be found in that post.

Problem(s)

Market Incentives

How do we create the incentives for the market to shift to pre-slaughter stunning?

The suffering shrimps experience at the end of their lives can be reduced by rendering them unconscious prior to slaughter through the use of electrical stunning technology. However, producers currently have very little incentive to implement pre-slaughter stunning as it’s expensive and few buyers require it. Even relatively forward-thinking retailers often can’t push an initiative through internally without some leverage (as they need to be able to convince their higher-ups that this is something worth doing and to persuade their suppliers to invest in the technology).

To solve this, we buy stunners for producers if they commit to stunning a minimum of 100 million shrimps every year and have a buyer (such as a supermarket) who commits to buying those stunned shrimps.

However, even though our intervention removes some of these barriers to implementation, we often get responses from the industry such as:

...we have consulted our sales teams and they do not see that the market demands this type of solution at the moment.

Therefore, this issue will not be a priority for 2025.

Currently, the main incentive we can provide is through an “early mover advantage” - being able to access a free stunner if they believe this is going to be a market requirement in the future.

Market Transition

How do we deal with the Supply/Demand problem when transitioning a market?

A big problem when transitioning a market is that supply is slow to grow without demand, and demand can’t really exist without supply. In other words, it can be hard for a retailer to commit to only buying stunned shrimps if they are not able to source stunned shrimps.

Similarly, a producer likely won’t start stunning shrimps until there is a clear demand to do so. Often, buyers and sellers have strong relationships, so switching suppliers usually isn’t simple. Buyers also typically don’t know the reality of supply and, in many cases, just don’t have the direct leverage to ask for the transition. So for most producers we work with, they’ve only committed to stunning a certain percentage of their supply (usually the minimum amount we require), and yet have many more shrimps they could stun.

We need to figure out how to incentivise producers to want to stun more shrimps and to enable retailers to access stunned shrimps without needing to change their supply chains.

Strategy

Existing Policy Tools

In 2011, Jayson Lusk published a paper titled The Market for Animal Welfare. In it, he argues that existing policy tools aimed at improving farm animal welfare (specifically meat taxes, process regulations, and labeling/certification schemes) often fall short due to various economic and behavioural limitations.

- Process regulations, such as banning specific farming practices, can unintentionally encourage producers to adopt alternative methods that might not substantially improve animal welfare, and without broader market controls, may simply shift production to less regulated regions.

- Meat labels and certifications typically only influence a niche market of ethically motivated consumers willing to pay higher prices, thereby limiting their effectiveness in addressing animal welfare issues across the broader industry or influencing consumers who prioritise price or abstain entirely.

- Meat taxes, though intended to reduce meat consumption and thus indirectly improve animal welfare, often disproportionately impact lower-income groups, encounter significant political resistance, and do not directly compel producers to adopt higher welfare standards.

Instead, he proposes to create an index of animal welfare being produced on the farm and assign "credits" based on production that can be sold in a newly constructed market. Which brings us to...

Cage-Free Impact Incentives

Another organisation trying to tackle this Supply/Demand problem is Global Food Partners (GFP). They were struggling to convince companies in Asia to switch to cage-free.

Essentially, they faced the following problems:

- Low supply of cage-free eggs: Most commercial eggs in Asia come from conventional battery cage systems, and cage-free production may not meet demand.

- Product identity and traceability: Preserving the identity of cage-free eggs in Asia's complex supply chain is complicated and expensive.

- Transportation costs & lack of infrastructure: Low volumes of cage-free eggs in nascent markets limit economies of scale and necessary infrastructure.

- Disease & flock health: Limited cage-free egg producers increase the risk of supply disruption due to disease outbreaks and flock health issues.

- High cost: Traceability issues, supply chain complexities, and limited supply drive up the cost of cage-free eggs.

- Time constraints: Farms need to be set up immediately to ensure sufficient egg availability by the end of 2025.

Their solution was to look to other industries, and they were inspired by innovations in aviation fuel and palm oil. In other words, bringing the concept of “Credits” to animals. Essentially, through the use of Cage-Free Impact Incentives, food businesses can offset their use of caged eggs and fulfill their commitments on time, even in challenging markets.

For credits to work, GFP realised that they would need the following three things:

- A facilitator of the credits: in this case, this is the role that GFP itself would play.

- Buyers for the credits: GFP worked with corporates in Asia to commit to buying credits in order to fulfill their cage-free commitments.

- And access to an audited supply chain: Essentially, a way to verify that these eggs are actually cage-free. Fortunately, there are now a number of certification schemes that can audit for cage-free.

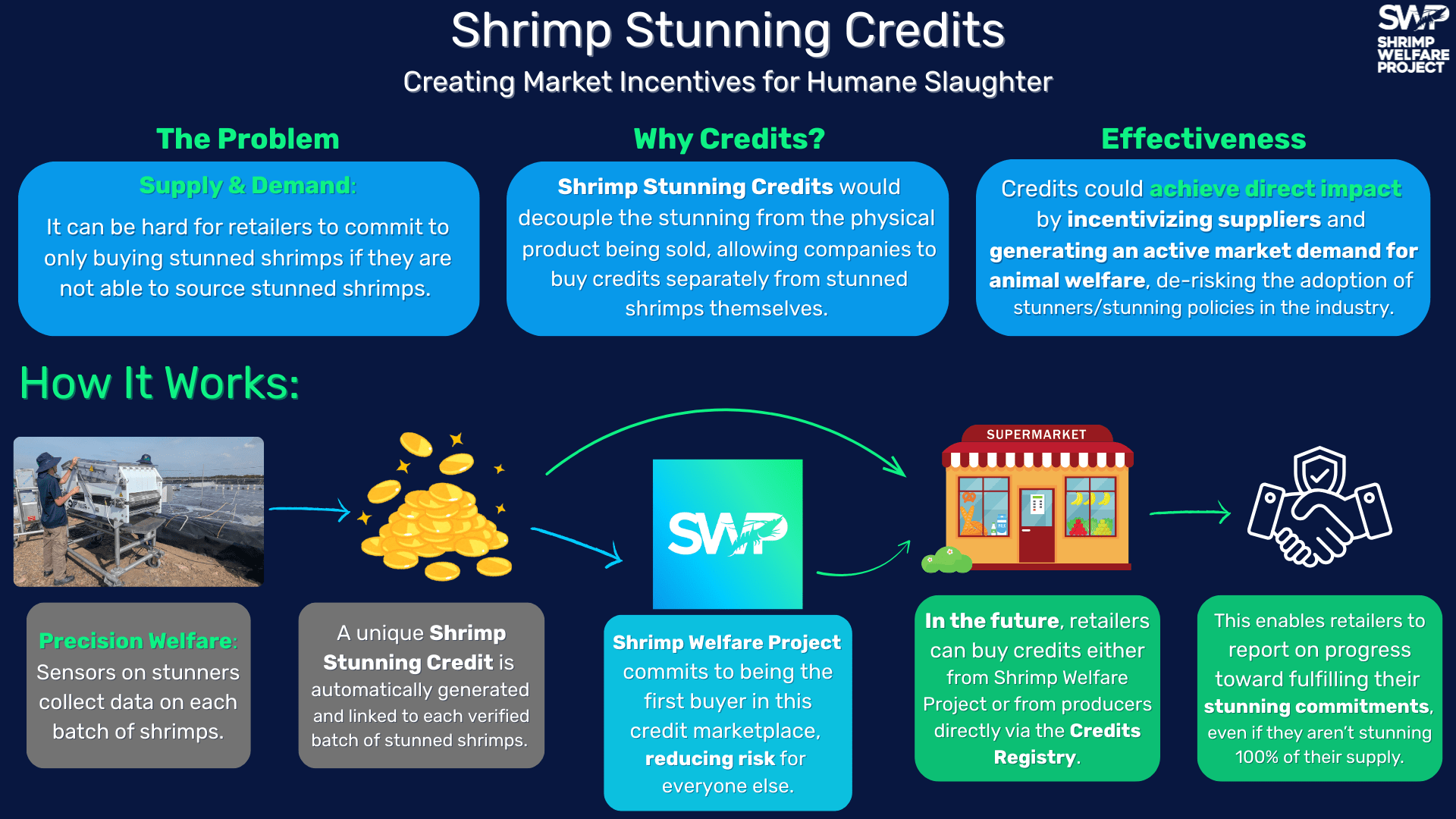

Shrimp Stunning Credits

So, inspired by Global Food Partners, we think a similar system of Market Incentives (or “Shrimp Stunning Credits”) could be the answer to our problems. Essentially, we want to decouple the stunning from the physical product being sold, allowing companies to register, buy and trade stunning credits separately from the stunned shrimps themselves.

This has multiple benefits:

- It achieves direct impact: With credits, suppliers can be incentivised to stun additional shrimps, even if the direct buyers of those shrimps don’t care if they’re stunned.

- It demonstrates market demand: By creating a system where stunning credits can be bought, we can support the development of stunned shrimps globally by accelerating investment and de-risking the adoption of stunners (or stunner policies) for both producers and buyers.

Buying Credits

Credits seem to help solve the Market Transition problem, but not necessarily the Market Incentives problem. We think that Shrimp Welfare Project buying credits could help solve the incentives problem.

We’re excited about credits because one of the big insights we had while developing our current strategy of buying stunners in the first place was the realisation that with some ideas, we could “pay for welfare at scale”. We think the idea of developing the infrastructure for stunning credits could be impactful on its own, but we want to take our “buying welfare” approach to stunners and also apply it to credits, both setting up the infrastructure and also being the first buyers of credits.

Ultimately, the goal would be to sell these credits back into the system, but we want to kickstart the adoption of credits by just being a big buyer right out of the gate.

Precision Aquaculture

We need to ensure that only verified supply is being credited. GFP solves this problem through certification, but this isn’t currently available for shrimps. We think that the emerging use of on-farm continuous data monitoring (or Precision Aquaculture) can solve this problem.

If we go back to the three things that GFP discovered needed to be in place for Credits to work, we can apply this to shrimp stunning:

- We’d need a facilitator of the buying of credits - as before, this is the role that us as the NGO will likely take.

- For buyers, our hope is that corporates will fill this role in the future, but in the beginning, this will also be a role that Shrimp Welfare Project will play to stimulate the market demand.

- But then we have the issue of an audited supply. For GFP, this was solved through certification schemes, but there is currently no certification scheme for stunned shrimps. This is where we’re hoping Precision Aquaculture, or Precision Welfare, can come into play.

Certification schemes are slow to adapt to changes and often have an unusual incentive structure where their customers are the producers themselves, so trying to be too innovative or progressive can cost them business.

We think Precision Welfare could be another way of verifying that the shrimps have been stunned. Installing devices onto shrimp stunners, for example, could automate the tracking of stunned shrimps. Once a shrimp has been stunned, we can verify that it has been stunned and generate a unique credit. Another reason I’m excited about this is that it incentivises the installation of tracking devices on farms and automates the transfer of that data to a verifiable 3rd party database.

Cage-Free Impact Incentives | Shrimp Stunning Credits | ||

Facilitator | Global Food Partners | Facilitator | Shrimp Welfare Project |

Buyers | Corporates | Buyers | Shrimp Welfare Project ⇒ Corporates |

Auditing | Certifiers | Auditing | Precision Aquaculture |

How it works

To try to pull this all together into a cohesive picture:

- Data Collection: Sensors on stunners capture key parameters (e.g., voltage, duration, shrimp movement pre/post-stun).

- Data Transmission: Data is securely sent to and stored in a blockchain-based or centralised "Credits Registry" for auditability.

- Credit Generation: Once a batch of shrimp is verified as stunned, a unique Shrimp Stunning Credit is automatically generated and linked to that batch.

- Shrimps are typically sold by "count", which refers to the number of shrimps per kg (so 100 count refers to a batch of shrimps who each weigh ~10g, 30 count refers to shrimps weighing ~33g, and so on).

- As this is already the prevalant method of trading shrimps in the industry, we assume that credits will be assigned per kg, rather than per shrimp.

- Credits Registry: The credits are stored in a registry, which notes key information about the credit (i.e. where the shrimps were stunned, who owns the credit currently etc.)

- Shrimp Welfare Project buys credits: Shrimp Welfare Project will be the first buyers in this credit marketplace, creating the immediate financial incentive for stunning / credit adoption.

- (Future) Retailers buy credits: From either Shrimp Welfare Project, or from producers directly (via a Credits Registry).

- Reporting on commitments: This also enables retailers to report progress toward fulfilling their stunning commitments, though it's important their claim language is accurate and in line with their supply chain model (i.e. "Supporting the adoption of pre-slaughter electrical stunning")

Further thoughts

Cost-Effectiveness

We think the impact per $ of this could range significantly, depending on whether we’re ultimately able to sell our credits back to the market.

Obviously, there are a number of uncertainties we have around this idea, and we would probably need to hire someone full-time for this project if we were to take it on. For example, we don’t currently know how much we should charge per credit. And our default cost-effectiveness of buying the stunners has a nice built-in yearly impact multiplier. But with credits, we’d be paying on a “per kg” basis, not a “per shrimp per year” basis.

Though ultimately, the cost-effectiveness doesn’t need to be the same, as our hope would be that we can sell these on in the future to retailers. This idea is kind of high-risk, high-reward in terms of impact. The potential impact of shrimps per dollar would be within a range - from us never re-selling a credit to us selling back all credits. But we’re also of the opinion that this could be cost-effective even if we never sell back any credits (due to having accelerated adoption of stunners).

Expanding Credits

An exciting recent development in the area of donor offsetting for the animal space is FarmKind’s “Compassion Calculator”. Essentially, they ask consumers to enter some numbers to calculate the impact of their diet, and then provide them with a number they can donate to offset the impact of their diet. This started as a small feature on their website but quickly became one of their most effective tools for engaging new donors. In particular, it seems to work because:

- It decouples action from diet change by reducing defensive reactions and cognitive dissonance that often prevent engagement with animal welfare issues.

- And it enables broader advocacy. The donation-focused message provides a way for influencers to discuss helping farm animals without making their audience defensive or uncomfortable.

There are a number of ways credits could expand in the future in the animal welfare space. Firstly, I think Shrimp Welfare Project could find uses for credits outside of shrimp stunning. In particular, once we develop our welfare outcome metrics, this seems like a very useful horizontal application of this idea.

But it doesn’t need to stop at shrimps (or cage-free); we could apply it to other animals. Using Precision Aquaculture / Precision Livestock Farming could be a means of bypassing certification schemes by getting tracking data on farms and pumping it into verifiable 3rd party systems. If done correctly, credits could create a price premium within the industry that generates an active market demand for animal welfare.

Finally, both of these solutions still require NGOs or corporations to be the buyers of the credits, but what if there was an Animal Welfare Marketplace where credits could be bought directly by donors themselves? This takes the idea of “offsets” and makes it much more direct. People could even opt to offset the consumption of others - no longer requiring people who consume animal products to also be willing to pay more for their welfare, this willingness to pay can come from elsewhere.

How You Can Help

The Shrimp Stunning Credits idea is still in its early stages, and we could really use some help from people with relevant skills. If you've got experience with blockchain, sensor tech, data analytics, or have worked with similar credit systems (like carbon credits), I'd love to chat! Feel free to email aaron@shrimpwelfareproject.org if you think you might be able to contribute (I'll also be at AVA (US) and EAG London in the coming weeks if you'd prefer to chat in person).

Hi Angelina, Austin, and Vasco :)

Apologies for all the confusion here - in terms of the idea I'm presenting in the post I think Vasco has done a really great job of summarising the idea above.

But I think the conversation above has helped me recognise a distinction that I don't think I'd articulated particularly well in my post, which is that I see a difference between the application of credits for contexts like shrimp stunning, and the wider application of credits for animal welfare more broadly:

Also, I've just realised that I've referenced @Vasco Grilo🔸's comments a few times in this reply to help clarify my thinking - just wanted to say that I really appreciate your help in articulating the points I wanted to make!