No one has ever seen an AGI takeoff, so any attempt to understand it must use these outside view considerations.

—[Redacted for privacy]

What? That’s exactly backwards. If we had lots of experience with past AGI takeoffs, using the outside view to predict the next one would be a lot more effective.

—My reaction

Two years ago I wrote a deep-dive summary of Superforecasting and the associated scientific literature. I learned about the “Outside view” / “Inside view” distinction, and the evidence supporting it. At the time I was excited about the concept and wrote: “...I think we should do our best to imitate these best-practices, and that means using the outside view far more than we would naturally be inclined.”

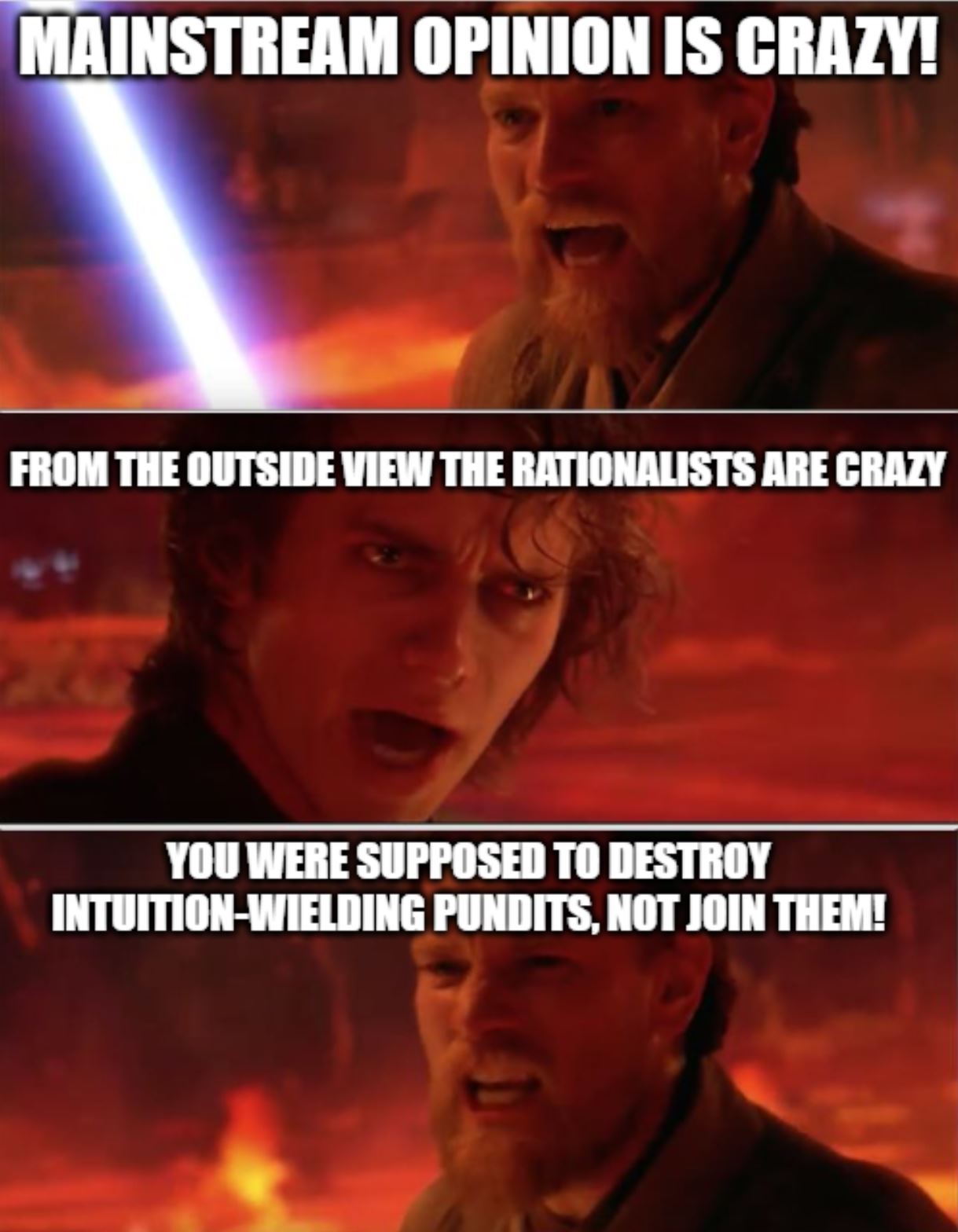

Now that I have more experience, I think the concept is doing more harm than good in our community. The term is easily abused and its meaning has expanded too much. I recommend we permanently taboo “Outside view,” i.e. stop using the word and use more precise, less confused concepts instead. This post explains why.

What does “Outside view” mean now?

Over the past two years I’ve noticed people (including myself!) do lots of different things in the name of the Outside View. I’ve compiled the following lists based on fuzzy memory of hundreds of conversations with dozens of people:

Big List O’ Things People Describe As Outside View:

- Reference class forecasting, the practice of computing a probability of an event by looking at the frequency with which similar events occurred in similar situations. Also called comparison class forecasting. [EDIT: Eliezer rightly points out that sometimes reasoning by analogy is undeservedly called reference class forecasting; reference classes are supposed to be held to a much higher standard, in which your sample size is larger and the analogy is especially tight.]

- Trend extrapolation, e.g. “AGI implies insane GWP growth; let’s forecast AGI timelines by extrapolating GWP trends.”

- Foxy aggregation, the practice of using multiple methods to compute an answer and then making your final forecast be some intuition-weighted average of those methods.

- Bias correction, in others or in oneself, e.g. “There’s a selection effect in our community for people who think AI is a big deal, and one reason to think AI is a big deal is if you have short timelines, so I’m going to bump my timelines estimate longer to correct for this.”

- Deference to wisdom of the many, e.g. expert surveys, or appeals to the efficient market hypothesis, or to conventional wisdom in some fairly large group of people such as the EA community or Western academia.

- Anti-weirdness heuristic, e.g. “How sure are we about all this AI stuff? It’s pretty wild, it sounds like science fiction or doomsday cult material.”

- Priors, e.g. “This sort of thing seems like a really rare, surprising sort of event; I guess I’m saying the prior is low / the outside view says it’s unlikely.” Note that I’ve heard this said even in cases where the prior is not generated by a reference class, but rather from raw intuition.

- Ajeya’s timelines model (transcript of interview, link to model)

- … and probably many more I don’t remember

Big List O’ Things People Describe As Inside View:

- Having a gears-level model, e.g. “Language data contains enough structure to learn human-level general intelligence with the right architecture and training setup; GPT-3 + recent theory papers indicate that this should be possible with X more data and compute…”

- Having any model at all, e.g. “I model AI progress as a function of compute and clock time, with the probability distribution over how much compute is needed shifting 2 OOMs lower each decade…”

- Deference to wisdom of the few, e.g. “the people I trust most on this matter seem to think…”

- Intuition-based-on-detailed-imagining, e.g. “When I imagine scaling up current AI architectures by 12 OOMs, I can see them continuing to get better at various tasks but they still wouldn’t be capable of taking over the world.”

- Trend extrapolation combined with an argument for why that particular trend is the one to extrapolate, e.g. “Your timelines rely on extrapolating compute trends, but I don’t share your inside view that compute is the main driver of AI progress.”

- Drawing on subject matter expertise, e.g. “my inside view, based on my experience in computational neuroscience, is that we are only a decade away from being able to replicate the core principles of the brain.”

- Ajeya’s timelines model (Yes, this is on both lists!)

- … and probably many more I don’t remember

What did “Outside view” mean originally?

As far as I can tell, it basically meant reference class forecasting. Kaj Sotala tells me the original source of the concept (cited by the Overcoming Bias post that brought it to our community) was this paper. Relevant quote: “The outside view is ... essentially ignores the details of the case at hand, and involves no attempt at detailed forecasting of the future history of the project. Instead, it focuses on the statistics of a class of cases chosen to be similar in relevant respects to the present one.” If you look at the text of Superforecasting, the “it basically means reference class forecasting” interpretation holds up. Also, “Outside view” redirects to “reference class forecasting” in Wikipedia.

To head off an anticipated objection: I am not claiming that there is no underlying pattern to the new, expanded meanings of “outside view” and “inside view.” I even have a few ideas about what the pattern is. For example, priors are sometimes based on reference classes, and even when they are instead based on intuition, that too can be thought of as reference class forecasting in the sense that intuition is often just unconscious, fuzzy pattern-matching, and pattern-matching is arguably a sort of reference class forecasting. And Ajeya’s model can be thought of as inside view relative to e.g. GDP extrapolations, while also outside view relative to e.g. deferring to Dario Amodei.

However, it’s easy to see patterns everywhere if you squint. These lists are still pretty diverse. I could print out all the items on both lists and then mix-and-match to create new lists/distinctions, and I bet I could come up with several at least as principled as this one.

This expansion of meaning is bad

When people use “outside view” or “inside view” without clarifying which of the things on the above lists they mean, I am left ignorant of what exactly they are doing and how well-justified it is. People say “On the outside view, X seems unlikely to me.” I then ask them what they mean, and sometimes it turns out they are using some reference class, complete with a dataset. (Example: Tom Davidson’s four reference classes for TAI). Other times it turns out they are just using the anti-weirdness heuristic. Good thing I asked for elaboration!

Separately, various people seem to think that the appropriate way to make forecasts is to (1) use some outside-view methods, (2) use some inside-view methods, but only if you feel like you are an expert in the subject, and then (3) do a weighted sum of them all using your intuition to pick the weights. This is not Tetlock’s advice, nor is it the lesson from the forecasting tournaments, especially if we use the nebulous modern definition of “outside view” instead of the original definition. (For my understanding of his advice and those lessons, see this post, part 5. For an entire book written by Yudkowsky on why the aforementioned forecasting method is bogus, see Inadequate Equilibria, especially this chapter. Also, I wish to emphasize that I myself was one of these people, at least sometimes, up until recently when I noticed what I was doing!)

Finally, I think that too often the good epistemic standing of reference class forecasting is illicitly transferred to the other things in the list above. I already gave the example of the anti-weirdness heuristic; my second example will be bias correction: I sometimes see people go “There’s a bias towards X, so in accordance with the outside view I’m going to bump my estimate away from X.” But this is a different sort of bias correction. To see this, notice how they used intuition to decide how much to bump their estimate, and they didn’t consider other biases towards or away from X. The original lesson was that biases could be corrected by using reference classes. Bias correction via intuition may be a valid technique, but it shouldn’t be called the outside view.

I feel like it’s gotten to the point where, like, only 20% of uses of the term “outside view” involve reference classes. It seems to me that “outside view” has become an applause light and a smokescreen for over-reliance on intuition, the anti-weirdness heuristic, deference to crowd wisdom, correcting for biases in a way that is itself a gateway to more bias...

I considered advocating for a return to the original meaning of “outside view,” i.e. reference class forecasting. But instead I say:

Taboo Outside View; use this list of words instead

I’m not recommending that we stop using reference classes! I love reference classes! I also love trend extrapolation! In fact, for literally every tool on both lists above, I think there are situations where it is appropriate to use that tool. Even the anti-weirdness heuristic.

What I ask is that we stop using the words “outside view” and “inside view.” I encourage everyone to instead be more specific. Here is a big list of more specific words that I’d love to see, along with examples of how to use them:

- Reference class forecasting

- “I feel like the best reference classes for AGI make it seem pretty far away in expectation.”

- “I don’t think there are any good reference classes for AGI, so I think we should use other methods instead.”

- Analogy

- Analogy is like a reference class but with lower standards; sample size can be small and the similarities can be weaker.

- “I’m torn between thinking of AI as a technology vs. as a new intelligent species, but I lean towards the latter.”

- Trend extrapolation

- “The GWP trend seems pretty relevant and we have good data on it”

- “I claim that GPT performance trends are a better guide to AI timelines than compute or GWP or anything else, because they are more directly related.”

- Foxy aggregation (a.k.a. multiple models)

- “OK that model is pretty compelling, but to stay foxy I’m only assigning it 50% weight.”

- Bias correction

- “I feel like things generally take longer than people expect, so I’m going to bump my timelines estimate to correct for this. How much? Eh, 2x longer seems good enough for now, but I really should look for data on this.”

- Deference

- “I’m deferring to the markets on this one.”

- “I think we should defer to the people building AI.”

- Anti-weirdness heuristic

- “How sure are we about all this AI stuff? The anti-weirdness heuristic is screaming at me here.”

- Priors

- “This just seems pretty implausible to me, on priors.”

- (Ideally, say whether your prior comes from intuition or a reference class or a model. Jia points out “on priors” has similar problems as “on the outside view.”)

- Independent impression

- i.e. what your view would be if you weren’t deferring to anyone.

- “My independent impression is that AGI is super far away, but a lot of people I respect disagree.”

- “It seems to me that…”

- i.e. what your view would be if you weren’t deferring to anyone or trying to correct for your own biases.

- “It seems to me that AGI is just around the corner, but I know I’m probably getting caught up in the hype.”

- Alternatively: “I feel like…”

- Feel free to end the sentence with “...but I am not super confident” or “...but I may be wrong.”

- Subject matter expertise

- “My experience with X suggests…”

- Models

- “The best model, IMO, suggests that…” and “My model is…”

- (Though beware, I sometimes hear people say “my model is...” when all they really mean is “I think…”)

- Wild guess (a.k.a. Ass-number)

- “When I said 50%, that was just a wild guess, I’d probably have said something different if you asked me yesterday.”

- Intuition

- “It’s not just an ass-number, it’s an intuition! Lol. But seriously though I have thought a lot about this and my intuition seems stable.”

Conclusion

Whenever you notice yourself saying “outside view” or “inside view,” imagine a tiny Daniel Kokotajlo hopping up and down on your shoulder chirping “Taboo outside view.”

Many thanks to the many people who gave comments on a draft: Vojta, Jia, Anthony, Max, Kaj, Steve, and Mark. Also thanks to various people I ran the ideas by earlier.

As a last thought here (no need to respond), I thought it might useful to give one example of a concrete case where: (a) Tetlock’s work seems relevant, and I find the terms “inside view” and “outside view” natural to use, even though the case is relatively different from the ones Tetlock has studied; and (b) I think many people in the community have tended to underweight an “outside view.”

A few years ago, I pretty frequently encountered the claim that recently developed AI systems exhibited roughly “insect-level intelligence.” This claim was typically used to support an argument for short timelines, since the claim was also made that we now had roughly insect-level compute. If insect-level intelligence has arrived around the same time as insect-level compute, then, it seems to follow, we shouldn’t be at all surprised if we get ‘human-level intelligence’ at roughly the point where we get human-level compute. And human-level compute might be achieved pretty soon.

For a couple of reasons, I think some people updated their timelines too strongly in response to this argument. First, it seemed like there are probably a lot of opportunities to make mistakes when constructing the argument: it’s not clear how “insect-level intelligence” or “human-level intelligence” should be conceptualised, it’s not clear how best to map AI behaviour onto insect behaviour, etc. The argument also hadn't yet been vetted closely or expressed very precisely, which seemed to increase the possibility of not-yet-appreciated issues.

Second, we know that there are previous of examples of smart people looking at AI behaviour and forming the impression that it suggests “insect-level intelligence.” For example, in Nick Bostrom’s paper “How Long Before Superintelligence?” (1998) he suggested that “approximately insect-level intelligence” was achieved sometime in the 70s, as a result of insect-level computing power being achieved in the 70s. In Moravec’s book Mind Children (1990), he also suggested that both insect-level intelligence and insect-level compute had both recently been achieved. Rodney Brooks also had this whole research program, in the 90s, that was based around going from “insect-level intelligence” to “human-level intelligence.”

I think many people didn’t give enough weight to the reference class “instances of smart people looking at AI systems and forming the impression that they exhibit insect-level intelligence” and gave too much weight to the more deductive/model-y argument that had been constructed.

This case is obviously pretty different than the sorts of cases that Tetlock’s studies focused on, but I do still feel like the studies have some relevance. I think Tetlock’s work should, in a pretty broad way, make people more suspicious of their own ability to perform to linear/model-heavy reasoning about complex phenomena, without getting tripped up or fooling themselves. It should also make people somewhat more inclined to take reference classes seriously, even when the reference classes are fairly different from the sorts of reference classes good forecasters used in Tetlock’s studies. I do also think that the terms “inside view” and “outside view” apply relatively neatly, in this case, and are nice bits of shorthand — although, admittedly, it’s far from necessary to use them.

This is the sort of case I have in the back of my mind.

(There are also, of course, cases that point in the opposite direction, where many people seemingly gave too much weight to something they classified as an "outside view." Early under-reaction to COVID is arguably one example.)