The views expressed here are my own, not those of my employers.

Summary

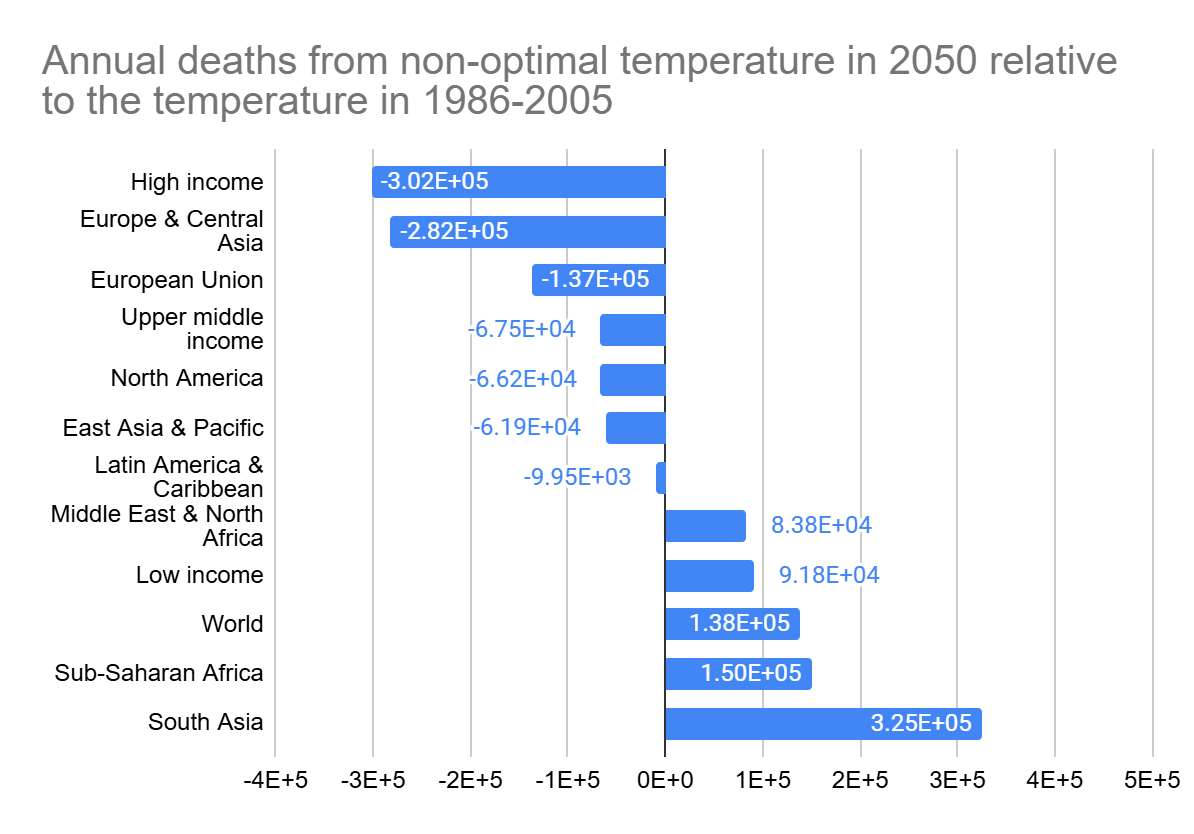

- I estimated the annual deaths and death rate from non-optimal temperature in 2030, 2050 and 2090 relative to the temperature in 1986-2005, by region and income group of The World Bank, for a global warming of 2.5 ºC by 2100. I concluded the annual deaths from non-optimal temperature from 1986-2005 to 2050:

- Increase in low and lower middle income countries, and decrease in upper middle and high income countries.

- Globally, increase by 138 k, which is:

- 0.224 % of all the deaths in 2023.

- 1.71 % of all the deaths from air pollution in 2021.

- 3.05 times the annual deaths from natural disasters from 2010 to 2019.

- It seems to me there is still significant uncertainty about whether global warming is good/bad from the point of view of changing global deaths from non-optimal temperature.

- I suspect the indirect effects of global warming are very overrated.

- I determine a cost-effectiveness for stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) of 2.95*10^-4 DALY/$, which is:

- 2.97 % of mine for GiveWell’s top charities.

- 0.905 % of mine for Founders Pledge’s Climate Change Fund (CCF).

- 0.00197 % of mine for corporate campaigns for chicken welfare, such as the ones supported by The Humane League (THL).

Future deaths from non-optimal temperature

I estimated the annual deaths and death rate from non-optimal temperature in 2030, 2050 and 2090 relative to the temperature in 1986-2005 by region and income group of The World Bank. I relied on:

- Data on the annual death rate from non-optimal temperature relative to the temperature in 1986-2005, accounting for changes in cold and heat-related mortality, for “2°C of warming by mid-century, and 2.5°C by 2100” from Human Climate Horizons. This was the 39th percentile global warming according to the Metaculus’ community on 15 July 2024, i.e. slightly better than the median scenario.

- Data on medium population projections from the World Population Prospects.

The data and results are in this Sheet. Below I only show results for the annual deaths and death rate from non-optimal temperature in 2050 relative to the temperature in 1986-2005. I chose that year because 2030 felt too early to capture concerns about a warming world, and 2090 too late for predictions to be reliable.

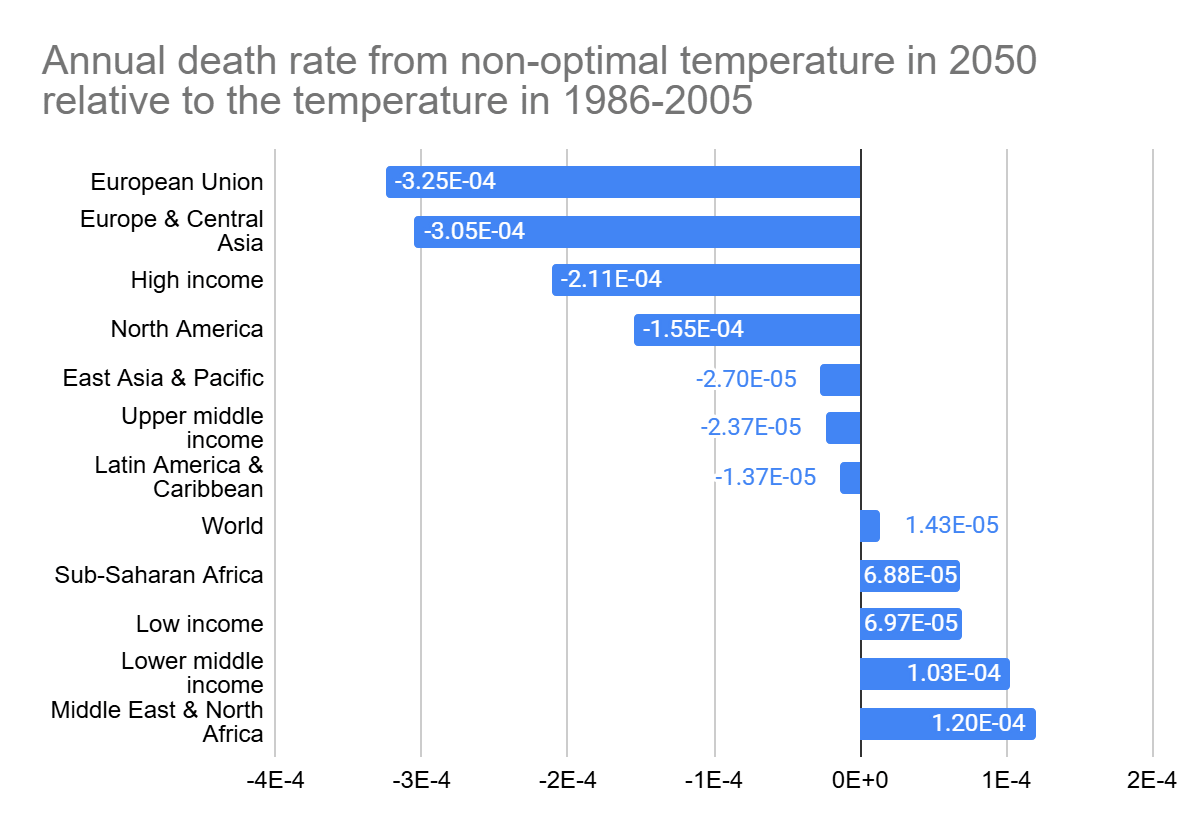

For a global warming of 2 ºC by 2050, I concluded the annual deaths from non-optimal temperature:

- Decrease in:

- 4 regions, Europe and Central Asia, North America, East Asia and Pacific, and Latin America and Caribbean.

- 2 income groups, high and upper middle income countries.

- Increase in:

- 3 regions, Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia.

- 2 income groups, low and lower middle income countries.

- Globally, increase by 138 k, which is:

- 0.224 % (= 138*10^3/(61.65*10^6)) of all the deaths in 2023.

- 1.71 % (= 138*10^3/(8.08*10^6)) of all the deaths from air pollution in 2021.

10.9 % of the sum of the absolute values of all entities[1]. So it seems to me there is still significant uncertainty about whether global warming is good/bad from the point of view of changing global deaths from non-optimal temperature.

- 3.05 (= 138*10^3/(45.3*10^3)) times the annual deaths from natural disasters from 2010 to 2019.

- Possibly an underestimate of the expected deaths because the mean global warming by 2100 is arguably higher than 2.5 ºC. In any case, I suppose the conclusions suggested by the above qualitatively hold.

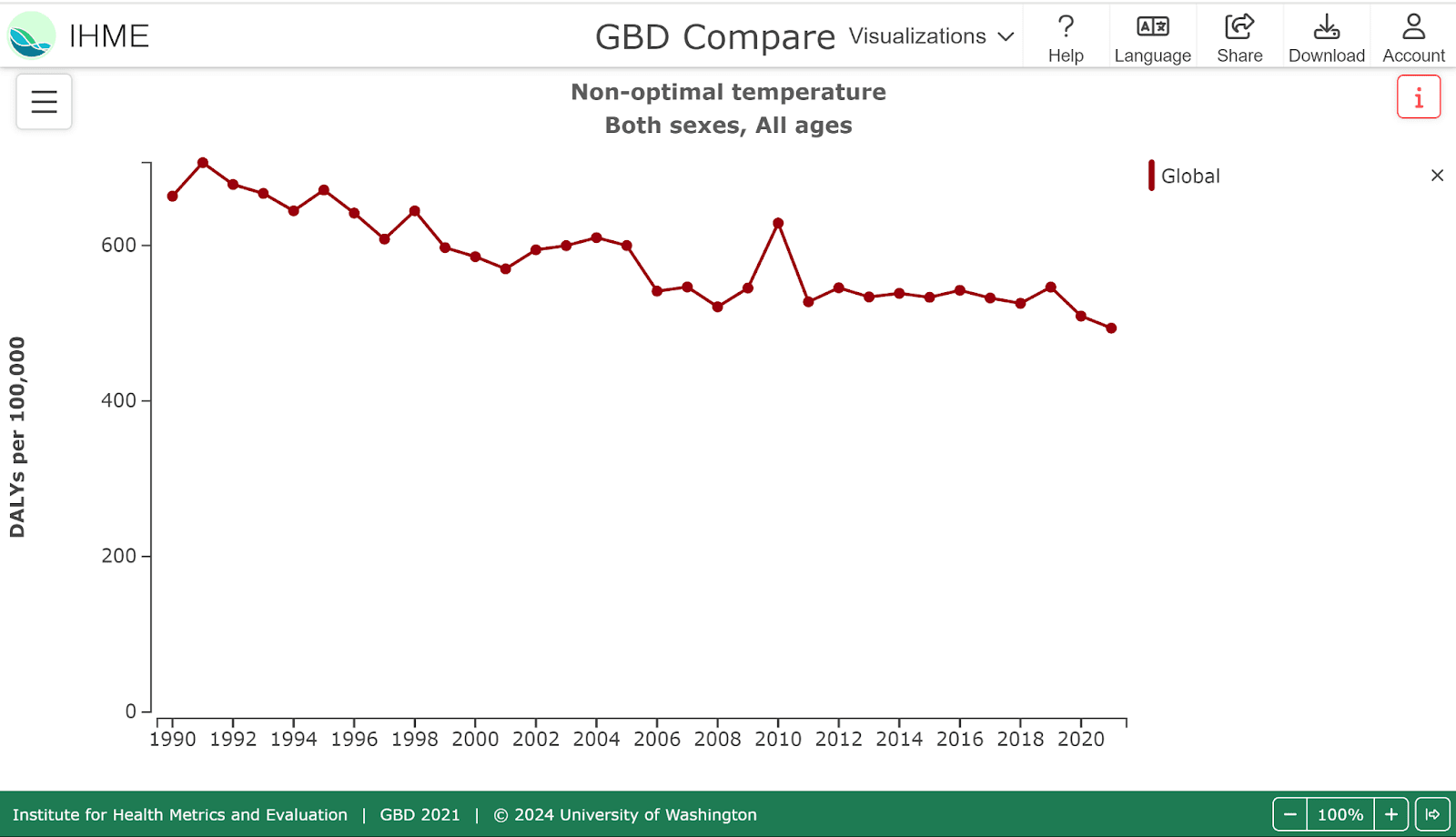

It is also unclear to me whether global warming has so far increased/decreased global deaths from non-optimal temperature. Zao et al. (2021) found a decrease studying 750 locations in 43 countries:

“From 2000–03 to 2016–19, the global cold-related excess death ratio changed by −0·51 percentage points (95% eCI −0·61 to −0·42) and the global heat-related excess death ratio increased by 0·21 percentage points (0·13–0·31), leading to a net reduction in the overall ratio.”

The disease burden per capita of non-optimal temperature has been decreasing.

On this overall topic, I liked Our World in Data’s (OWID's) 2 posts on how many people die from extreme temperatures, and how this could change in the future. Particularly, the graph below showing global warming mostly affects lower and lower middle income countries.

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/change-heat-deaths-gdp

I shared a draft of this post with Johannes Ackva. He commented that the sophisticated case for caring about climate change has to do with the indirect effects of global warming, like increased risk of conflicts. I suspect such indirect effects are very overrated:

- I got this sense from skimming John Halstead’s report Climate Change & Longtermism.

- The direct effects have been very overrated. Some argued (and maybe still argue) more than 1.5 ºC of global warming by 2100 would be catastrophic, whereas I think it is more accurate to say it may well be positive/negative (in expectation).

- I believe the sign uncertainty of the indirect effects, i.e. whether they are good/bad (in expectation), will tend to be larger than that of the direct effects, and this already seems quite large to me.

- Climate change might have indirect cascade effects, but so do other problems, and it is unclear to me whether the magnitude of the direct effects as a fraction of that of the indirect effects is specially small for climate change.

- Appealing to indirect cascade effects or other known unknowns feels a little like a regression to the inscrutable, which is characterised by the following pattern:

- Arguments for high risk initially focus on aspects which are relatively better understood (e.g. changes in the deaths from non-optimal temperature).

- Further analysis frequently shows the risk from such aspects has been overestimated, and is in fact quite low.

- Then discussions move to more poorly understood aspects of the risk (e.g. global warming might increase the risk of conflicts).

- The direct effects just look too small to cause significant indirect effects. For instance, the overall death rate in India is predicted to be 0.880 % in 2050, whereas the death rate from non-optimal temperature is only predicted to increase 0.006 pp from 1986-2005 to 2050, i.e. just 0.682 % (= 6*10^-5/0.00880) of the overall death rate projected for 2050.

Cost-effectiveness of stratospheric aerosol injection

SAI is “a proposed method of solar geoengineering (or solar radiation modification [SRM]) to reduce global warming. This would introduce aerosols into the stratosphere to create a cooling effect via global dimming and increased albedo, which occurs naturally from volcanic winter”.

I determined a cost-effectiveness for SAI of 2.95*10^-4 DALY/$ (= 6.44*10^6/(21.8*10^9)). I got this from the ratio between:

- An annual benefit of SAI of 6.44 MDALY (= 138*10^3*46.7), which I obtained multiplying:

- My estimate for the increase in the annual deaths from non-optimal temperature from 1986-2005 to 2050 for 2.5 ºC of global warming by 2100 of 138 k.

- A disease burden per death from non-optimal temperature of 46.7 DALY (= 1.68*10^6/(36.0*10^3)), which is the ratio between the disease burden and deaths from environmental heat and cold exposure in 2021 from the Global Burden of Disease study (GBD) of 1.68 MDALY and 36.0 k.

- An annual cost of SAI of 21.8 G$/year (= 1*21.8*10^9), which I computed from the product between:

- 1 ºC (= 2.5 - 1) of global cooling, which I guess would eliminate the deaths mentioned just above by bringing global warming to 1.5 ºC by 2100.

- The annual cost of SAI per degree of cooling from Smith 2020 of 18 G 2020-$/year/ºC, i.e. 21.8 G$/year/ºC (= 18*10^9*1.21).

My estimate for the cost-effectiveness of SAI is:

- 2.97 % (= 2.95*10^-4/0.00994) of mine for GiveWell’s top charities.

- 0.905 % (= 2.95*10^-4/0.0326) of mine for CCF.

- 0.00197 % (= 2.95*10^-4/15.0) of mine for corporate campaigns for chicken welfare, such as the ones supported by THL.

I speculate a leveraged intervention like research on or advocacy for SAI can be up to 100 times as cost-effective as directly implementing it, which would bring the cost-effectiveness up to 0.0295 DALY/$ (= 100*2.95*10^-4), i.e. roughly the same level as that of CCF. However, I do not see how such leveraged interventions could be more cost-effective than the best animal welfare interventions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Johannes Ackva for feedback on the draft. Johannes noted he is “not really the right person to review the climate science part of this” nor “a peer reviewer in the sense of having reviewed everything thoroughly”.

- ^

This metric would be 1 if annual deaths increased in every single entity, in which case sign uncertainty would be minimal.

Thanks for this, Vasco, thought-provoking as always!

I do not have too much time to discuss this, but I want to point out that I am pretty unconvinced by the argument for why indirect effects should be easy to discount by the type of the argument you make. So, to be clear, I am not arguing that the conclusion is necessarily wrong (I think this would require stronger arguments), but rather that the argumentation strategy here does not work.

As far as I understand it your argument for "indirect effects cannot be very large" is something like:

1. Deaths from heat are very overstated and not that significant and they capture the most important direct effect.

2. A claim for strong indirect effects is then implausible because onto that direct effect you need to sequence a bunch of very uncertain additional effects with uncertain signs.

Insofar as is this a correct representation of your argument -- please let me know -- I think it has a couple of problems:

1.

a. Dying from heat stress is a very extreme outcome and people will act in response to climate change much earlier than dying. For example, before people die from heat stress, they might abandon their livelihoods and migrate, maybe in large numbers.

b. More abstractly, the fact that an extreme impact outcome (heat death) is relatively rare is not evidence for low impact in general. Climate change pressures are not like a disease that kills you within days of exposure and otherwise has no consequence.

2.

a. You seem to suggest we are very uncertain about many of the effect signs. I think the basic argument why people concerned about climate change would argue that changes will be negative and that there be compounding risks is because natural and human systems are adapted to specific climate conditions. That doesn't mean they cannot adapt at all, but that does mean that we should expect it is more likely that effects are negative, at least as short-term shocks, than positive for welfare. Insofar as you buy a story where people migrate because of climate impacts, for example, I don't think it is unreasonable to say that increased migration pressures are more likely to increase tensions than to reduce them, etc.

b. I think a lot of the other arguments on the side of "indirect risks are low" you cite are ultimately of the form (i) "indirect effects in other causes are also large" or (ii) "pointing to indirect effects make things inscrutable and unverifiable". (i) might be true but doesn't matter, I think, for the question of whether warming is net-bad and (ii) is also true, but does nothing by itself on whether those indirect effects are real -- we can live in a world where indirect effects are rhetorically abused and still exist and indeed dominate in certain situations!

Likewise! Thanks for the thoughtful comment.

It seems like a fair representation.

Agreed. However:

This makes sense. On the other hand, one could counter global warming will be good because:

Agreed. I would just note that i) can affect prioritisation across causes.

Thanks!

I think I remain confused as to what you mean with "all deaths from non-optimal temperature".

It is clear that the data source you cite (GBD, focused on current deaths) will not feature nor proxy what people concerned about compounding risks from climate are concerned about.

So to me it seems you are saying "I don't trust arguments about compounding risks and the data is evidence for that" whereas the data is inherently not set up to include that concern and does not really speak to the arguments that people most concerned about climate risk would make.

As said before, I think it is fine to say "I don't trust arguments about compounding risks" and I am probably with you there to a large degree at least compared to people most concerned about this, but I don't think the data from GBD is additional evidence for that mistrust, as far as I can tell.

By crude analogy, if you believed that COVID restrictions had a big toll on the young and this will affect long-run impacts somehow, pointing to few COVID deaths amongs this age cohort would not be evidence against this concern.

I mean the difference between the deaths for the predicted and ideal temperature. From OWID:

The deaths from non-optimal temperature are supposed to cover all causes (temperature is a risk factor for death rather than a cause of death in GBD), not just extreme heat and cold (which only account for a tiny fraction of the deaths; see my last comment). I say "supposed" because it is possible the mortality curves above are not being modelled correctly, and this applies even more to the mortality curves in the future.

My understanding is that (past/present/future) deaths from non-optimal temperature are supposed to include conflict deaths linked to non-optimal temperature. However, I am not confident these are being modelled correctly.

I was not clear, but in my last comment I mostly wanted to say that deaths from non-optimal temperature account for the impact of global warming not only on deaths from extreme heat and cold, but also on cardiovascular or kidney disease, respiratory infections, diabetes and all others (including conflicts). Most causes of death are less heavy-tailed than conflict deaths, so I assume we have a better understanding of how they change with temperature.

Ok, so I think we converge pretty much then -- essentially what I am saying is that people concerned about compounding risks would argue that these are not modeled correctly in GBD and that there is much more uncertainty there (and that the estimate is probably an underestimate, from the perspective of taking the compounding risk view seriously).

Makes sense. Just to clarify, the data on deaths and disease burden from non-optimal temperature until now are from GBD, but the projections for the future death rates from non-optimal temperature are from Human Climate Horizons.

Thanks, Bradley, and welcome to the EA Forum! Strongly upvoted.

If adequately modelling humidity would increase heat deaths, I wonder whether it would also decrease cold deaths, such that the net effects is unclear.

As illustrated below, deaths from extreme cold and heat accounted for only a tiny fraction of the deaths from non-optimal temperature in 2015 in some countries, which attenuates the effect you are describing.