Kelsey Piper recently posted on Vox "Caring about the future doesn’t mean ignoring the present" which argues that effective altruism hasn’t abandoned its roots and that longtermist goals for the future don’t hurt people in the present.

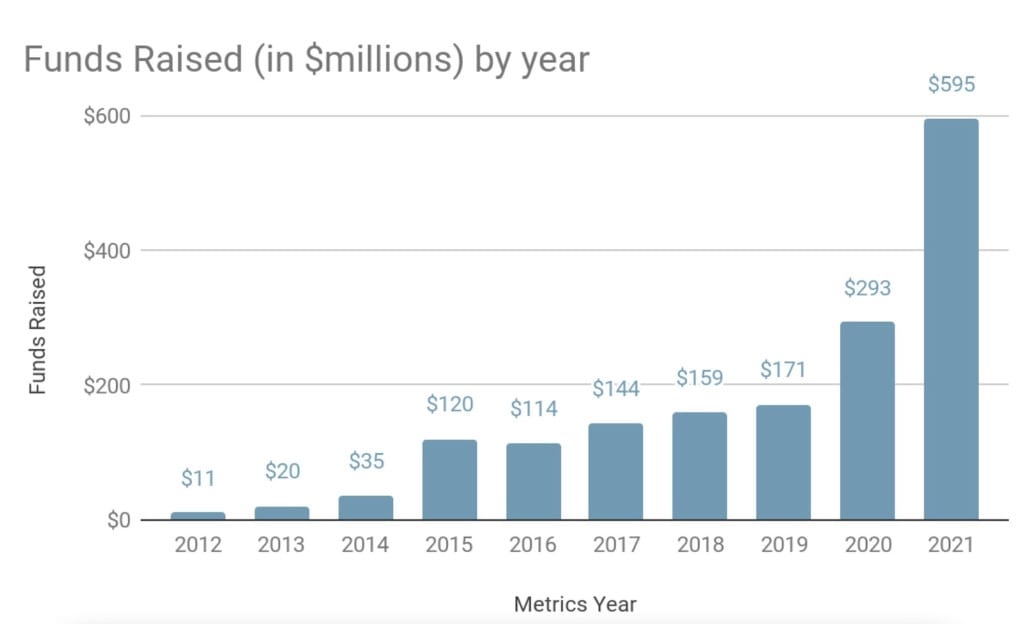

In particular it highlights that effective altruism is growing on all fronts and highlight's GiveWell's fundraising.

It also highlights that the growth of the movement brings a wider range of people in more than it pulls funding away from one cause to another: it's a symbiotic relationship.

You could imagine the EA movement growing to the point where further growth is mostly about persuading people of intra-movement priority changes, but that day is very far in the future.

This is not to say that I think effective altruism should just be about whatever EAs want to do or fund. Prioritization of causes is at the heart of the movement — it’s the “effective” in effective altruism.

But the recent funding data does incline me toward worrying less that new focuses for effective altruism will come at the direct expense of existing ones, or that we must sacrifice the welfare of the present for the possibilities of the future.

In a growing, energized, and increasingly powerful movement, there is plenty of passion — and money — to go around.

Thanks for sharing this!

I think this quote from Piper is worth highlighting:

I broadly agree with this, except I think the first "if" should be replaced with "insofar as." Even as someone who works full-time on existential risk reduction, it seems very clear to me that longtermism is causing this obvious and immediate harm; the question is whether that harm is outweighed by the value of pursuing longtermist priorities.

GiveWell growth is entirely compatible with the fact that directing resources toward longtermist priorities means not directing them toward present challenges. Thus, I think the following claim by Piper is unlikely to be true:

To make that claim, you have to speculate about the counterfactual situation where effective altruism didn't include a focus on longtermism. E.g., you can ask:

My guess is that the answer to all three is "yes", though of course I could be wrong and I'd be open to hear arguments to the contrary. In particular, I'd love to see evidence for the idea of a 'symbiotic' or synergistic relationship. What are the reasons to think that the focus on longtermism has been helpful for more near-term causes? E.g., does longtermism help bring people on board with Giving What We Can who otherwise wouldn't have been? I'm sure that's the case for some people, but how many? I'm genuinely curious here!

To be clear, it's plausible that longtermism is extremely good for the world all-things-considered and that longtermism can coexist with other effective altruism causes.

But it's very clear that focusing on longtermism trades off against focusing on other present challenges, and it's critical to be transparent about that. As Piper says, "prioritization of causes is at the heart of the [effective altruism] movement."

In a nutshell: I agree that caring about the future doesn't mean ignoring the present. But it does mean deprioritising the present, and this comes with very real costs that we should be transparent about.