Many AI safety programs have acceptance rates in the 1–5% range. That can make it hard to tell when applying is actually worth your time.

In this post, we:

- Sketch a simple expected value (EV) model for “should I apply?”

- Illustrate the model using our upcoming pivotal research fellowship (deadline: Nov 30).

- Give a simple calculator you can plug your own numbers into.

You might have heard about many opportunities in AI safety having low acceptance rates (<5% is very common, we estimate our own base acceptance rate to be roughly 3.5%) and this can feel demotivating.

We think this intuition is often misleading.

First, and most importantly, your probability of being accepted might be higher than the base rate (especially if you’re reading this, hi!).

If you have low opportunity costs (e.g. you have free time or your alternative plan is low-paid), the Expected Value of applying can remain positive even if your probability of acceptance drops below the base rate.

Conversely, if you have high opportunity costs (e.g. a very busy schedule or a high-paying alternative option), the bar for applying is higher. For the math to work out, you generally need either a higher-than-average probability of success or you need to put a high value on the non-monetary outcomes of this fellowship (such as the research impact, network, or other career benefits).

We are interested in candidates avoiding two failure modes:

- Highly promising candidates self-selecting out of applying because they anchor on the 3.5% base rate.

- Candidates applying when the math clearly suggests they shouldn't (though we think this is rare).

The Model

To formalise this, we can treat the application as a bet. We generally model the decision using the following simplified equation:

Where:

- P(Success): Your estimated probability of being accepted.

- VFinancial: The stipend (£6k or £8k) plus ~£1,500 in estimated value for covered travel, accommodation, and meals.

- VIntangible: The value you assign to the network, mentorship, and altruistic impact of the fellowship.

- VCounterfactual: The income/value you would generate if you didn't do the fellowship (e.g., your job, a corporate internship).

- VInformation: The "Value of Information". Even a rejection provides data about your current fit for this type of role.

- CApplication: The opportunity cost of the hours spent applying. (Hours spent on application x Hourly Value)

We have implemented this logic into the calculator below.

The Calculator

Application EV CalculatorNotes on the Variables

The Cost of Applying: We estimate the application takes 2–4 hours for most applicants. The general application form will likely take you 1h to complete, and then any mentor you apply to will take an additional 15-90 minutes. To find out more about how much you value your time, check out Clearer Thinking’s Value of Time Calculator.

Probability of Acceptance: We expect this to be the hardest variable to calibrate yourself on.

- The Base Rate depends on the number of applications, but we estimate it will be around 3.5%.

- You are not a random draw from the total applicant pool. You have private information about your skills. However, assessing yourself is notoriously difficult.

- We cannot tell you your probability. The best we can do is point you to past cohorts. If your profile looks similar to some of the past fellows, your acceptance probability is likely considerably higher than the base rate. But we advise to not over-index on this, as we had great fellows with diverse backgrounds (from first semester undergrads to SWE with decades of industry experience).

- If you apply, you reduce the probability of acceptance for others slightly, but you increase it a lot for yourself.

Intangible Value: This variable captures everything that you expect to get that isn't VFinancial. We think this is the largest driver of value, but it is also very hard to estimate. We suggest breaking it down into:

- Personal Value: How much is it worth to you to pivot your career into AI safety? What value do you put on the career capital you gain and the network you’ll be more closely connected with?

- Altruistic Value: If you believe AI safety is the most pressing problem in the world, the value of contributing to it might be worth tens of thousands of "moral pounds" to you. Don't be afraid to assign a high monetary value to this if it reflects your true priorities.

- Note: Be aware that our fellowship will be far from the only input into the total value you'll achieve in your career, so try not to over-index on this single opportunity as the only path to impact.

Value of Information: As a simplifying assumption, we added a small fixed value (£10) to the model to represent the utility of the application process itself (structuring your thoughts on research) and the signal value of the result. For some people (e.g. those trying multiple adjacent fellowships) this could be considerably higher.

Examples

To illustrate how sensitive the EV is to your specific situation, here are two fictional examples describing common situations.

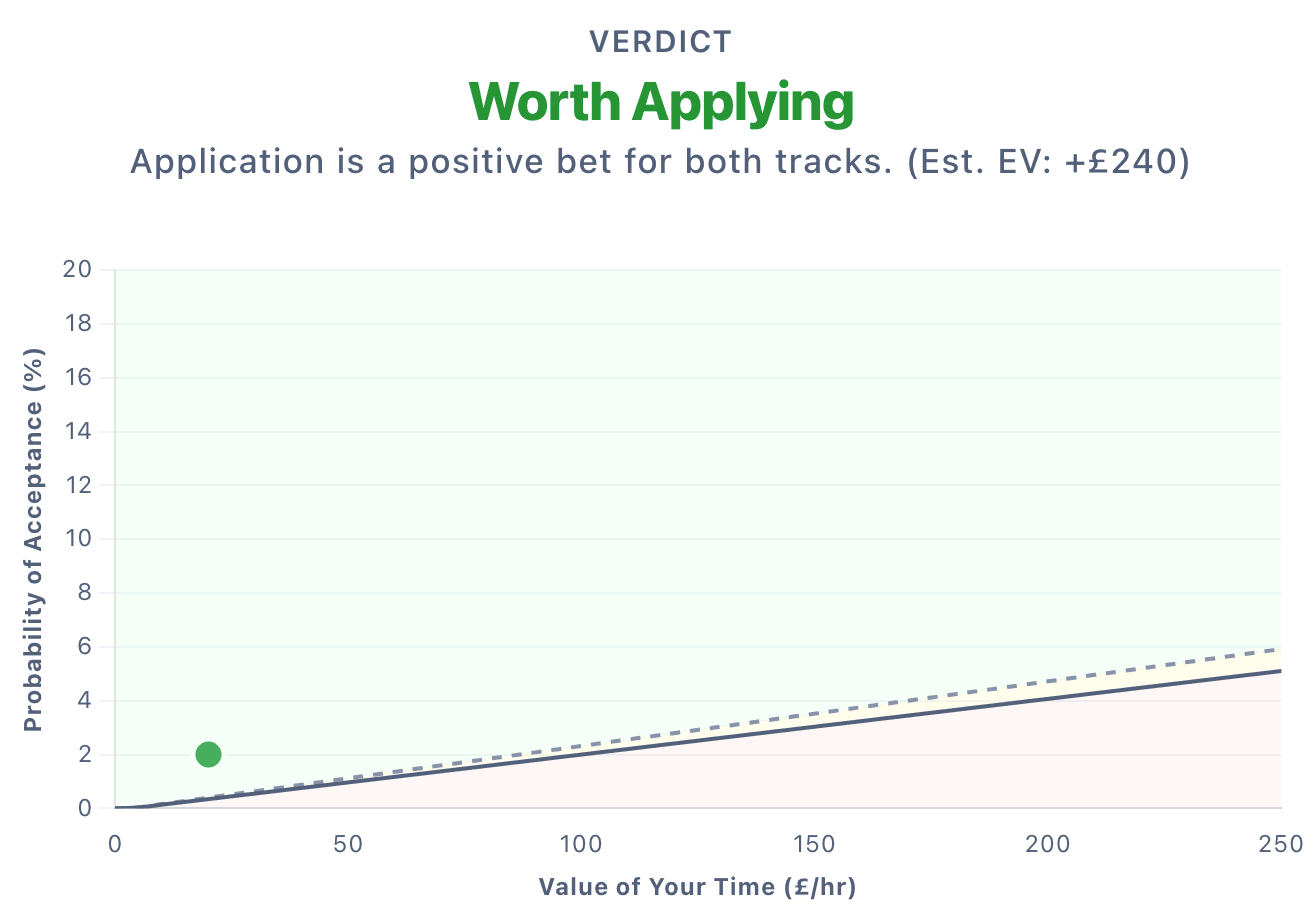

Case A: The Undergraduate

- Hourly Value: £20/hr (Cost to apply: £80 for 4 hours)

- Probability: 2% (They assess their application as a ‘stretch’.)

- Counterfactual Income: £3,000 (Part-time work)

- Intangible Value: £8,000

- Fellowship Value: £7,500

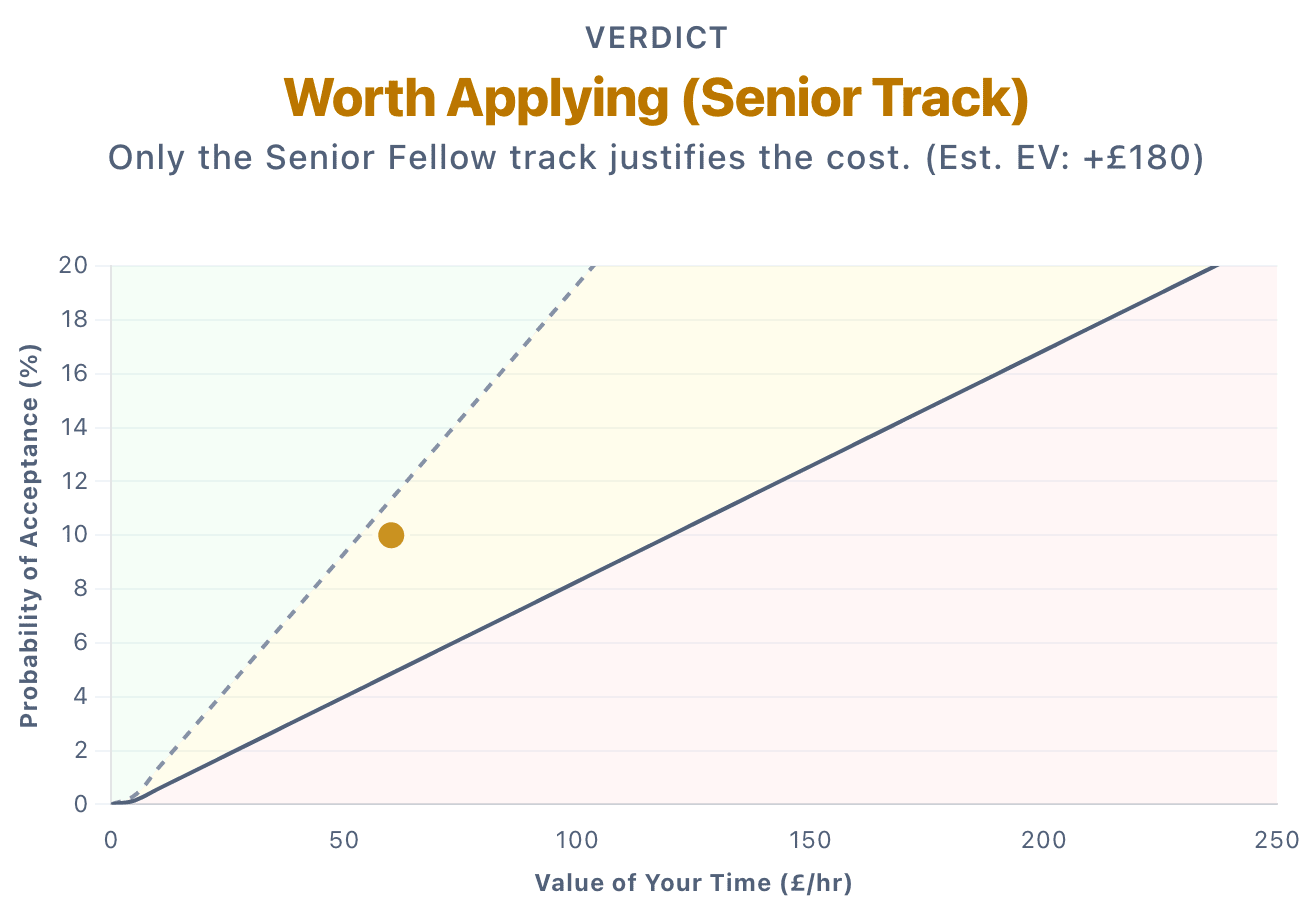

Case B: The Early-Career Professional

- Hourly Value: £60/hr (Cost to apply: £180 for 3 hours)

- Probability: 10%

- Counterfactual Income: £16,000 (Current job)

- Intangible Value: £10,000

- Fellowship Value: £7,500 (Normal) or £9,500 (Senior)

Here are some considerations:

- If applying takes 3 hours the math only works if you get the Senior Fellow spot. For the Normal Fellow spot, the EV is negative.

- If applying takes 2 hours, suddenly, the EV becomes positive though small even for the Normal Fellow spot.

- Potential conclusion: If you are on the fence, it might make sense to focus on making a short, targeted application. Reducing your time investment makes the bet cheap enough to be worth taking.

For a negative example, someone who thinks they have a 1% chance, values their time at £100/h, is unsure whether an AI safety career is what they want, and has a very strong counterfactual job might get a clearly negative EV from the calculator. That’s probably a good sign not to apply!

Caveats

This calculator is not a definitive decision-making tool. But it might nudge you into the direction of applying, or against it. Please keep in mind:

- You likely increase your probability of getting accepted by applying to more mentors. But each mentor application takes an additional 15-90 minutes, depending on the mentor.

- The calculator doesn’t take the marginal utility of money into account and treats every pound as equal. In reality, the cost of giving up a higher salary depends on your financial situation. If taking our stipend instead of a higher salary means "saving slightly less this year," that is very different from it meaning "not being able to pay rent".[1]

- If you apply to 10 fellowships and get into all of them, you can only accept one. The EV of applying to this specific fellowship drops if you are likely to secure a better offer elsewhere after having applied. The calculator assumes that if you get in, this is your best option. (Of course, the EV of ‘apply to all 10 fellowships’ can still be high.)

- The calculator assumes you can accurately estimate your own inputs, particularly your probability of acceptance. We worry about two opposing failure modes there:

- Imposter Syndrome: Highly competent people who underestimate their own potential, assigning themselves too low of a probability

- Overconfidence: Others might ignore the base rate entirely & not be aware that they are applying to a really competitive program.

- Your situation might be more complex. For example, some past fellows quit their jobs to switch into AI safety. This has often worked well, but it’s unclear how they’d have put this into the calculator.

- Sometimes applying creates opportunities even when rejected (e.g. referrals to other programs).

Final Thoughts

If you find the calculator outputs "Don't Apply," take a moment to stare at that result. Does it feel wrong? If so, listen to your gut and apply.

Does the calculator output "Apply" but you feel unsure? Then, just for once, trust the numbers and apply.

- ^

We also don't take into account risk aversion (the stakes of 'losing' ~3 hours are relatively low) or time discounting (the delay between applying and the fellowship is only 2-3 months).

As the demotivated person you referenced, I appreciate this! But I think the case for de-motivation is a bit stronger than presented in this calculation, so I'll try to steelman it.

First of all, consider the framing: you've assumed that if I don't get this fellowship I'll continue with the job I already have, and that if I don't apply I'll just have leisure time. In reality many applicants will be looking for a new opportunity, and if they don't get this they'll probably take something else. They might (as I am) be making as many applications as they have energy for, such that the relevant counterfactual is another application, rather than free time.

Here are some more specific points:

This leads to a much much more complicated equation! I asked GPT, to try to link this all together, and well... I'll just link its answer here.

So I remain pretty unsure as to whether it's worth it for myself personally, but I might put in an application anyway :)

Thanks a lot for engaging!

One general point: My rough guess is that acceptance rates have stayed largely constant across AI safety programs over the last ~2 years because capacity has scaled with interest. For example, Pivotal grew from 15 spots in 2024 to 38 in 2025. While the 'tail' likely became more exceptional, my sense is that the bar for the marginal admitted fellow has stayed roughly the same.

The model does assume that most applicants aren't spending 100% of their time/energy on applications. However, even if they were, I feel like a lot of this is captured by how much they value their time. I think that the counterfactual of how they spend their time during the fellowship period (which is >100x more hours than the application process) is the much more important variable to get right.

This is correct. I assumed most people would take this into account (e.g. subtract their current job's networking value from the fellowship's value), but I might add a note to make this explicit.

I’m less worried about this one. Since we set the fixed Value of Information quite conservatively already, and most people aren't constantly working on applications, I suspect this is usually small enough to be noise in the final calculation.

I agree this is real, but I think it's covered in the Value of Your Time. If you earn £50/hr but find applying on the weekend fun/interesting, you might set the Value of Your Time at £5/hr. If you are unemployed but find applying extremely aversive, you might price your time at e.g., £200/hr.

I also have the impression that these fellowships are getting more competitive each year. Do you share that perspective? If so, that would require a further adjustment to the calculation.