Introduction

This post kicks off a 5-part series exploring how to build infrastructure for a Profit for Good world—one where companies operate normally but lock 90%+ of profits to effective charities through their ownership structure.

Despite proven examples like Newman's Own ($600M+ donated) and clear competitive advantages, Profit for Good remains <0.1% of the economy. Why? The marketplace doesn't exist.

On the supply side: Philanthropists don't yet see how funding PFG companies can multiply their impact—every dollar invested can generate multiple dollars for charity annually through competitive advantages. Without evidence of these returns, capital doesn't flow.

On the demand side: Consumers, employees, and other stakeholders don't know PFG options exist, or assume charitable businesses must be inferior. They can't prefer what they don't know about or trust.

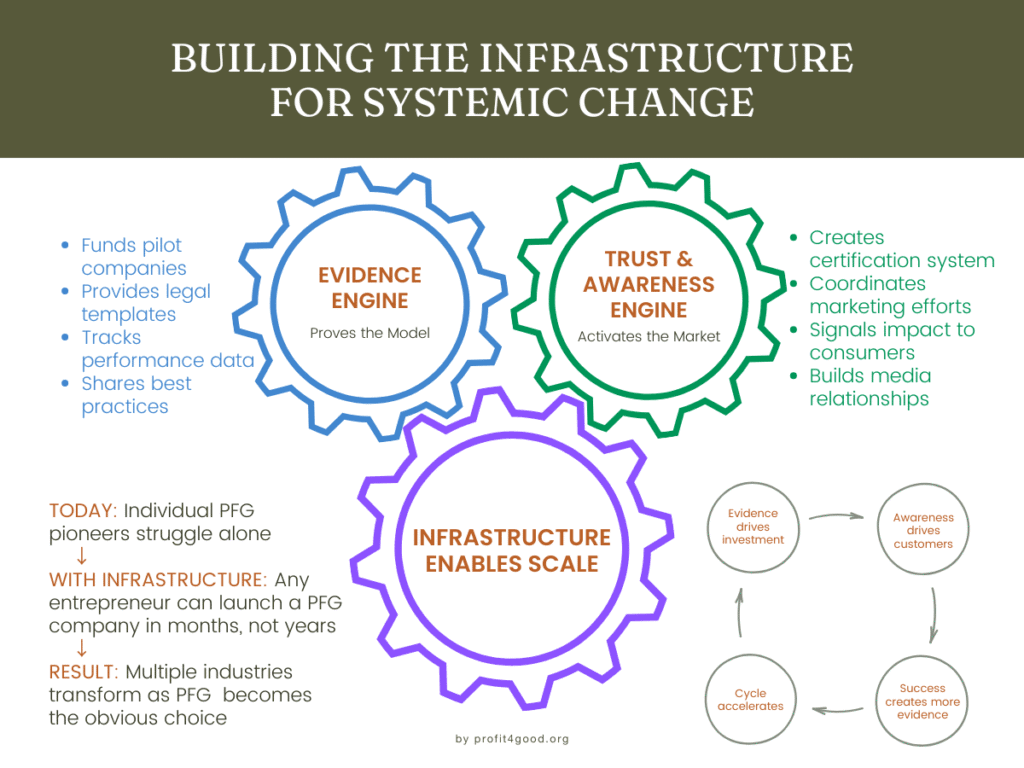

This series lays out concrete steps to build both sides of this marketplace, potentially redirecting trillions in corporate profits toward solving humanity's greatest challenges. This first article diagnoses the problem and introduces two solutions: an Evidence Engine to prove the multiplier effect with real data, and a Trust & Awareness Engine to connect PFG companies with the stakeholders who will drive their success.

I've linked to the original blog post, but the full article appears below for easier discussion. I'd particularly value the EA community's thoughts on systematically testing which business models multiply philanthropic impact most effectively.

Capitalism’s $10 Trillion Routing Error—And How to Fix It

Building Profit for Good Infrastructure: Part 1 of 5

Executive Summary

The Problem: Corporations generate $10+ trillion in annual profits while proven solutions to humanity’s greatest challenges—from malaria prevention to disaster relief—remain chronically underfunded. This isn’t malice; it’s a routing error in capitalism’s design.

The Solution: Profit for Good (PFG) companies operate identically to traditional businesses but lock 90%+ of profits to charity through their ownership structure. Examples like Newman’s Own ($600M+ donated) and Humanitix ($16.5M donated while disrupting Ticketmaster) prove the model works.

The Opportunity: When consumers choose between identical products, they systematically prefer ones that fund charity over enriching shareholders—creating competitive advantages that multiply philanthropic impact. Every dollar invested in PFG can generate multiples for charity through lower customer acquisition costs, better employee retention, and free media coverage.

The Barrier: Despite proven success, PFG remains <0.1% of the economy because the infrastructure doesn’t exist. Like organic food before its $65B transformation, PFG needs a functioning marketplace with both supply (funded companies) and demand (aware consumers).

The Path Forward: Two synchronized engines can fix this:

- Evidence Engine: Deploy $10-20M to test PFG across sectors, proving what works

- Trust & Awareness Engine: Create certification and marketing to help consumers find and trust PFG options

The Ask: Fund both engines to transform capitalism’s $10 trillion routing error into humanity’s largest philanthropic resource.

Malaria kills 600,000 people yearly, yet the entire global budget to fight it is just $4 billion1 what corporations earn in about 3.5 hours.2

This is capitalism’s routing error: profits flow automatically to those who need them least, while proven solutions to humanity’s greatest challenges go begging. But we know how to fix it. Newman’s Own has proven it for over 40 years, donating more than $600 million while competing head-to-head with Kraft3. Humanitix disrupts Ticketmaster while funding education worldwide4. The model works. So why are Profit for Good companies still less than 0.1% of the economy?5 Like organic food in 1990, PFG lacks the marketplace infrastructure to scale: funded companies on the supply side, aware consumers on the demand side. Building these two synchronized engines- Evidence and Trust & Awareness- is how we transform a $10 trillion routing error into humanity’s largest philanthropic resource.

Profit for Good companies operate exactly like traditional businesses but permanently donate at least 90% of profits to charity through their ownership structure.

In our previous series exploring Profit for Good, we established that these companies gain systematic competitive advantages—from higher customer conversion to lower employee turnover. We showed how these advantages compound into a philanthropic multiplier, where every dollar invested can generate a multiple of that for charity.

So, if the model works and multiplies impact, why are PFG companies still less than 0.1% of the economy?

The infrastructure doesn’t exist yet. By infrastructure, we mean capital sources, legal templates, certification systems, and public awareness campaigns that let any founder launch a PFG company in months, not years.

But infrastructure alone isn’t enough if consumers, employees, and other relevant economic actors don’t care. The entire model depends on people actually preferring companies that donate profits over those that enrich shareholders. Do they?

The Free Upgrade Test

In our Charity Choice analysis, we explored a “zero-cost prosocial preference”—the documented tendency for people to choose options that help others when all else is equal. Let’s make this even simpler with what we call the Free Upgrade Test.

Imagine you’re shopping for a laptop. Two identical models, same specs, same price: $1,000. The only difference? One enriches anonymous shareholders. The other prevents childhood blindness in India.

Which do you choose?

If you’re like most people, the choice feels obvious. When everything else is equal, why wouldn’t you choose the option that helps people? It’s literally a free upgrade—same laptop, added impact.

This intuitive preference extends beyond shopping. Given identical job offers at the same pay, would you rather work for a company enriching investors or one funding education? Given equal terms, would you rather partner with a business padding profits or preventing malaria?

The preference is so obvious it feels silly to state. Yet our entire economy is structured to ignore it.

Charity Choice, Quantified

Not surprisingly, hard data backs the existence of this preference. When researchers actually test what happens when people face these choices, the results are compelling:

Consumers pay more: An eBay study covering 60 million listings found that charity-linked items sold for 6% higher prices6—buyers literally paid extra to ensure their purchase helped others.

It scales with trust: Amazon Smile failed because it was hard to find and trivial (0.5% of purchase price donation).7 But when Patagonia pledged 100% of Black Friday sales to environmental causes, they saw 5x expected revenue—$10 million instead of $2 million.8

The pattern is clear: when people can choose between identical options, they systematically prefer the one that does good—if they know about it and trust it’s real.

Two Tales of Proof

Paul Newman didn’t set out to revolutionize capitalism. He just wanted to give holiday gifts to neighbors—homemade salad dressing in wine bottles. When they kept asking for more, he and his friend A.E. Hotchner decided to sell it properly.9

“Let’s give all the profits to charity,” Newman suggested10. Industry experts were incredulous—after all, who launches a food brand without planning to keep the profits?11

Today, Newman’s Own has donated over $600 million to charity while building an empire spanning dozens of products.12 They compete on quality alone. This isn’t charity subsidizing business. It’s business subsidizing charity through pure competitive excellence.

But for a modern example, look at Humanitix. Started by two friends frustrated with Ticketmaster’s extractive fees, they built a ticketing platform that works exactly the same but donates 100% of profits to education, healthcare, and other projects serving the developing world. In just a few years, they’ve donated $16.5 million AUD while processing millions of tickets annually13. They’re doubling every six months according to Google Cloud, taking market share from a near-monopoly14—not through guilt, but through better user experience and the simple fact that event organizers prefer helping better lives over enriching Ticketmaster’s shareholders.15

The Competitive Advantages Hidden in Plain Sight

These aren’t isolated cases. Where profits help save lives or otherwise better the world, the same systematic advantages emerge:

When employees know their work funds education instead of random investors, they work differently. When suppliers learn their client donates profits, they offer better terms. When journalists hear about a company giving everything away, they write stories traditional PR can’t buy.

To name a few advantages:

- Microsoft provides significant nonprofit discounts (up to 75% on select products)16

- Patagonia’s ownership announcement generated massive earned media coverage 17

- Mission-driven companies report stronger employee engagement and retention 18

These advantages compound into what we call the philanthropic multiplier. Every dollar invested in a PFG company leverages competitive advantages- lower costs, free media, loyal employees- to generate a multiple of that amount for charity. Yes, foundations already achieve perpetual giving through index funds, but PFGs can beat market returns through charity choice. It’s a perpetual engine where business success and charitable impact reinforce each other.

Which raises the question: if giving away profits creates competitive advantages that multiply philanthropic impact, why isn’t everyone doing it?

Why This Falls Through Every Crack: the Marketplace Problem

The answer is painfully simple: no one knows what to do with Profit for Good companies.

Consider how long it took traditional capitalism to develop. The idea of passive investors—people with no connection to a business beyond owning shares—funding companies to multiply their money wasn’t obvious or immediate. It took centuries to develop stock markets, limited liability, venture capital, and the entire infrastructure that now seems inevitable. The Dutch East India Company issued the first tradeable shares in 160219. Venture capital as we know it didn’t emerge until the 1940s20. Each innovation required new legal frameworks, new mental models, and new institutions.

Now we’re asking philanthropists to make a similar conceptual leap—from traditional giving to harnessing market forces that multiply their impact. Foundations already know how to generate perpetual returns through index funds and endowments. But PFG offers something more powerful: when consumers, employees, and partners systematically prefer companies that donate profits, those companies gain competitive advantages that create MORE profits to donate. The charity choice effect means these businesses can outperform traditional investments while directing all returns to charity.

Traditional foundation investing: Index fund → Market returns → Annual giving

PFG investing: Deploy capital → Company gains market share through charity choice → Superior returns → All to charity → Competitive advantages compound over time

This model is new, and almost no one has discussed how competitive advantages could drive its expansion, compared to centuries of traditional philanthropy and investing.

PFG faces the same infrastructure gap, compressed into years instead of centuries.

Entrepreneurs hear “give away 90%” and assume no upside. They miss that 10% of a $100M exit is still $10 million—plus a legacy worth bragging about.

Philanthropists and foundations freeze because PFG is neither grant nor conventional investment, so it dies in committee. Their entire infrastructure—grant applications, program officers, evaluation metrics—wasn’t built for this hybrid model. The idea that they could fund businesses that outperform traditional investments precisely because they give away profits? That requires rewiring how philanthropic capital gets deployed.

The ecosystem—impact investors, business schools, even nonprofits—doesn’t have a box for it. We spent 400 years building boxes for traditional capitalism. We’ve spent maybe 10 thinking about PFG.

Result: great idea, no infrastructure- and specifically, no functioning marketplace to connect PFG companies with the consumers and capital they need

Two Engines to Fix the Routing Error

Think about organic food. In 1990, it was a fringe movement21. Then came standards, certification, and infrastructure. Today it’s a $65 billion market in the U.S. alone22. But here’s what everyone forgets: organic needed BOTH supply (farmers willing to convert) AND demand (consumers willing to buy) to reach critical mass.

Profit for Good could be 1,000 times bigger, but it needs the same synchronized development. We need two engines that work together.

Engine #1: Evidence (Proving What Works)

Philanthropists are careful with money—as they should be. Talk is cheap; results move capital. The Evidence Engine systematically tests PFG across sectors to generate proof at scale.

Phase 1: Strategic Mapping A research team maps entire industries against PFG success factors: commodity products, trust deficits, easy switching, high margins. They identify the 20 most promising opportunities across insurance, payments, software-as-a service (SaaS), ticketing, and utilities. This isn’t picking winners—it’s running experiments in what have been researched to be the most promising contexts for PFGs.

Phase 2: Parallel Experiments Deploy $10-20M to launch 10-15 companies simultaneously across different sectors. Each gets standardized legal structures, shared back-office systems, and peer learning networks. Think of it as a controlled experiment: same PFG model, different industries. Which thrive? Which struggle? Why?

Phase 3: Pattern Recognition Track everything across the portfolio: customer acquisition costs, employee retention, media coverage, competitive response. When patterns emerge—”PFG works best in recurring revenue models” or “B2B outperforms B2C”—share findings immediately. Failed experiments are as valuable as successes.

Phase 4: Replication Playbooks Convert learnings into open-source playbooks. If insurance PFGs consistently see 40% lower customer acquisition costs, document exactly how. Create templates, tools, and training so the next wave can skip the learning curve.

The Evidence Engine tests three core hypotheses:

- Charity Choice creates measurable competitive advantage

- These advantages compound over time

- Success patterns are replicable across sectors

Once philanthropists see documented proof that PFG investments multiply their charitable impact through competitive advantages—with audited results from real companies, not just projections—capital will flow. When a proven model meets simple investment structures and clear cause alignment, the question shifts from “does this work?” to “which sectors should we test next?”

Engine #2: Trust & Awareness (Making It Real and Discoverable)

Evidence moves philanthropists. Trust and awareness move consumers. But here’s the critical insight: the biggest barrier isn’t skepticism about charity—it’s the assumption that charitable businesses must be inferior. The Trust & Awareness Engine proves there’s no hidden tradeoff: same quality, same price, better outcome.

The Trust & Awareness Engine creates both verification and discovery:

Building Trust Through Certification: Imagine scanning a QR code on your insurance card and seeing exactly how much went to disaster relief last quarter. That’s trust made tangible.

- Small companies (under $1M): Self-certify with public pledge

- Medium companies ($1-10M): Accountant verification (costs less than credit card processing fees)

- Large companies ($10M+): Full third-party audit

Creating Awareness Through Coordinated Marketing: Certification creates trust. Coordinated marketing creates awareness. Together, they create demand.

- Unified launch campaigns: “Same price. Same quality. Profits solve problems.”

- Cross-category discovery: PFG insurance customers learn about PFG coffee

- Shared marketing fund: Companies contribute to collective advertising

- Direct messaging that there’s no quality sacrifice—just better impact

Certification would be overseen by an independent nonprofit with rotating board members, preventing capture while maintaining credibility.

How the Engines Reinforce Each Other

Neither engine works alone. Evidence without trust and awareness means funded companies that consumers never discover. Awareness without evidence means consumer demand with nowhere to go. But together, they create the marketplace dynamics that transformed organic from fringe to mainstream.

Together, they create a virtuous cycle:

Evidence proves model → Philanthropists fund companies → Companies need customers → Trust & awareness deliver them → Success generates more evidence → More philanthropists join → Cycle accelerates

Each success makes the next easier. Every customer dollar now spins the flywheel and multiplies philanthropic impact.

The Path from Here to There

Years 1-2: Deploy $10 million across 10-20 companies. Test sectors systematically. Even failures teach valuable lessons while generating charitable impact.

Years 3-4: Early successes demonstrate the model. Media coverage becomes self-sustaining. Consumer awareness builds.

Year 5+: $100 million deployed. Multiple industries approaching tipping points. Billions flowing to charity annually.

The daily cost of delay: $27 billion to shareholders, thousands of preventable deaths, millions of animals suffering needlessly. Yet even “failure” succeeds—fund ten companies that collectively donate $100 million while learning what doesn’t work? That’s impact plus education.

Changing Everything by Changing Almost Nothing

This might be the most conservative revolution imaginable. Keep capitalism. Keep competition. Keep profit motives. Just change where profits go.

No new laws needed. No boycotts. No protests. Just building businesses that compete normally while automatically routing profits to solve problems instead of enriching those who already have plenty.

The real question isn’t whether we fix the routing error—only how fast. When someone offers you the same laptop that also prevents blindness, you take it. When someone offers the same insurance that also funds disaster relief, you switch. When someone builds the infrastructure to make these choices possible at scale, markets transform.

The infrastructure to fix this $10 trillion routing error won’t build itself. The marketplace needs both sellers and buyers, evidence and awareness, supply and demand.

If you’re a philanthropist: Fund the Evidence Engine to prove what works. If you’re an entrepreneur: Build a PFG company in a high-impact sector. If you’re anyone else: Share this vision with someone who can act on it.

Next in Part 2: Inside the Evidence Engine—why insurance might tip first, the quantitative screening matrix we’ll use, and insights from founders already building PFG companies.

- World Health Organization. (2023). World malaria report 2023, p. 45 https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023 (noting estimates of total 2022 malaria funding at $4.1 billion -around $11.2 million per day) ↩︎

- EU Tax Observatory, Global Tax Evasion Report 2024, Chapter 2 (“Trends In Global Corporate Profit Shifting”), Table 2.1. ↩︎

- Newman’s Own Foundation: “About Us – Our Impact.” (foundation website confirms “over $600 million donated”) https://newmansownfoundation.org/our-impact/ ↩︎

- BizBash: “All About This Charitable Booking Platform.” (Feb 2022) https://www.bizbash.com/production-strategy/registration-ticketing/article/22657492/all-about-this-charitable-booking-platform ↩︎

- Estimated based on broader social enterprise and impact investing data, as no direct global PFG metrics exist; for example, Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship & World Economic Forum (2024) estimates ~10 million social enterprises generate $2 trillion in annual revenue (~1.8% of projected 2025 global GDP of ~$110 trillion per IMF forecasts), while Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) (2024) sizes impact investing at $1.571 trillion in assets under management (~1.4% of GDP). PFG, as a strict subset with ≥90% profits to charity, is almost certainly <0.1%. Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship & World Economic Forum. (2024, April 18). “The State of Social Enterprise: A Review of Global Data 2013–2023.” Available at: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-state-of-social-enterprise-a-review-of-global-data-2013-2023/; Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). (2024). “Sizing the Impact Investing Market 2024.” Available at: https://thegiin.org/research/publication/sizing-the-impact-investing-market-2024/; International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2025, April). “World Economic Outlook Database.” Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2025/April. ↩︎

- Elfenbein, Daniel W. & McManus, Brian (2009, rev. 2010), p 3. A Greater Price for a Greater Good? Evidence that Consumers Pay More for Charity-Linked Products. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=965007 ↩︎

- Weatherbed, Jess. “Amazon is shutting down its ‘AmazonSmile’ charity program after a decade.” The Verge, 18 Jan 2023. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2023/1/19/23562036/amazon-closing-amazonsmile-charity-platform-announcement ↩︎

- Emma Fierberg, “After making $10 million in Black Friday sales, Patagonia is donating it all to saving the planet,” CNBC, 29 November 2016. Available at https://www.cnbc.com/2016/11/29/after-making-10m-in-black-friday-sales-patagonia-is-donating-it-all-to-saving-the-planet.html. ↩︎

- “From homemade gifts to grocery shelves, Paul Newman’s salad dressing started as Christmas presents poured into empty wine bottles.” – Mashed, 10 Aug 2017. https://www.mashed.com/79646/untold-truth-newmans/ ↩︎

- Mark Seal, “Inside the Family Battle for the Newman’s Own Brand Name,” Vanity Fair, August 2015 (online publ. July 23, 2015). Available at: https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2015/07/paul-newmans-own-family-feud-susan-newman ↩︎

- “Book Excerpt: Newman’s Own Story,” TIME, Nov 10 2003 https://time.com/archive/6670030/book-excerpt-newmans-own-story/ ↩︎

- Newman’s Own Foundation. “Our Mission.” NewmansOwn.com. Accessed July 8, 2025. https://newmansown.com/mission/ ↩︎

- Field, Shivaune. “Aussie Ticketing Platform Humanitix Hands Out $16.5 Million in Donations.” Forbes Australia, 29 Nov 2024. https://www.forbes.com.au/news/entrepreneurs/aussie-ticketing-platform-humanitix-hands-out-16-5m-in-donations/ (accessed July 10, 2025) ↩︎

- Google Cloud. “Humanitix: Closing the education gap with a world-class event-ticketing platform, powered by Google Cloud.” Customer Stories, accessed July 8, 2025. https://cloud.google.com/customers/humanitix ↩︎

- Erin McGrane, quoted on Humanitix, “Impact – 100 % of profits for good,” Humanitix USA Ltd., accessed 10 July 2025, https://humanitix.com/impact. “We switched our ticketing platform from Eventbrite to Humanitix for two key reasons: pricing and customer service. As a not-for-profit, we also deeply appreciate Humanitix’s mission-driven approach, which aligns perfectly with our values. We are completely satisfied with the platform’s performance and couldn’t be happier with our decision to switch”

↩︎ - Microsoft Corporation, “Nonprofit Offers & Discounts FAQ,” accessed Jul 2025, https://nonprofit.microsoft.com/en-us/get-started/faqs — see answer to “How much of a discount do nonprofits receive?” (“…discounts of up to 75 percent on many Microsoft Cloud services”) ↩︎

- NewsWhip. (2022, September 20). “Despite Twitter backlash, the Patagonia climate action resonated where it mattered.” Available at: https://www.newswhip.com/2022/09/despite-twitter-backlash-patagonia-climate-moves-resonated-where-it-mattered/newswhip.com

↩︎ - Harvard Business Review Analytic Services. The Business Case for Purpose. Sponsored by the EY Beacon Institute. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2015. Available at https://5025095.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/5025095/Claromentis_sr/Pdf/ey-the-business-case-for-purpose.pdf (accessed 10 July 2025)

↩︎ - Investopedia. (2023, October 31). “What Was the First Company to Issue Stock?” Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/08/first-company-issue-stock-dutch-east-india.asp

↩︎ - Wikipedia. (2024, July 11). “History of private equity and venture capital.” Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_private_equity_and_venture_capital

↩︎ - USDA Economic Research Service (ERS). (2001). “U.S. Organic Farming Emerges in the 1990s: Adoption of Certified Systems.” Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 770, p. 2. Available at: https://ers.usda.gov/sites/default/files/_laserfiche/publications/42396/31544_aib770_002.pdf (Certified organic farmland was 935,450 acres in 1992, rising to 1,346,558 acres by 1997, representing 0.23% of total U.S. cropland in 1997, confirming its niche, fringe status in the early 1990s).

↩︎ - Source: Organic Trade Association, April 23, 2025 https://ota.com/about-ota/press-releases/growth-us-organic-marketplace-accelerated-2024 ↩︎

Surely it's going to be much more difficult for a PFG company to raise capital? Stocks are (in some way) related to future profits. If you are locked in to giving 90% away then doesn't that mean that stocks will trade at a much lower price and hence it will be much harder for VCs to get their return?

Yeah you are very limited in ability to exchange equity in exchange for cash. So for regular investors you could raise money with bonds.

The idea would be philanthropists would be in the position that for-profit investors would be in normal businesses because they could multiply their money to charity. See the below article for more information (and the whole previous blog series)

https://profit4good.org/above-market-philanthropy-why-profit-for-good-can-surpass-normal-returns/

How have you factored this into your calculations? Surely if the returns are much lower, the total % of the market that could be run like this is much smaller?

What might help you conceptually is not to think of donations and shareholders as a separate thing (i.e. donations are something that limits returns) but rather think of it as business where charities are the shareholders (not conferring any disadvantage moreso than any other shareholder).

The returns are not lower. They are higher, because economic actors have a non-zero preference for charities but they can operationally do what normal businesses can (hence Humanitix's meteoric rise).

The limiting factor right now is philanthropic capital. And if philanthropists realize they can get more money to charity through this model, then they would be motivated to use it because it offers the opportunity to multiply impact. And then if the evidence base gets stronger, they can use debt (leveraged buyouts) to expand beyond what philanthropic resources would allow.

See my below article on why PFGs should have a competitive advantage.

Stakeholder non-zero preference > business advantage > philanthropic multiplier opportunity

https://profit4good.org/from-charity-choice-to-competitive-advantage-the-power-of-profit-for-good/

Executive summary: This evidence-driven proposal argues that "Profit for Good" (PFG) companies—businesses that permanently commit ≥90% of profits to effective charities—can outperform traditional firms due to measurable competitive advantages, but remain underdeveloped due to missing marketplace infrastructure; the author proposes building two engines (Evidence and Trust & Awareness) to catalyze a functioning ecosystem and redirect trillions in corporate profits to high-impact philanthropy.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.