This is a crosspost for Pigou's Dial by Bryan Caplan, which was originally published on Bet on It on 24 May 2023.

[Subtitle.] The theory of market failure versus the practice of government regulation

A good intro econ class rubs psychologically normal humans the wrong way… for the first ten weeks. Instead of teaching a familiar pile of Social Desirability Bias, intro econ classes tell students about scarcity, supply-and-demand, and the efficiency of perfect competition.

Around week 11, however, intro econ classes switch gears - and start teaching the theory of market failure. Above all, they present the concepts of positive and negative externalities, along with public goods and public bads. Which gives politically-aware students a great excuse to continue believing everything they thought before the class started.

“Privatize and let the market work? Bah, haven’t you heard of positive externalities?! Pigou clearly showed that markets undersupply goods with positive externalities, which is why we need widespread government ownership.”

“Deregulate and let the market work? Bah, haven’t you heard of negative externalities?! Pigou clearly showed that markets oversupply goods with negative externalities, which is why we need ubiquitous government regulation.”

Which brings me to my big message for fellow econ professors: If you allow your students to leave your class with these grotesque confusions, you have utterly failed. The true lesson of Pigou is not that existing economic policy makes sense. The true lesson of Pigou is that existing economic policy is a disgrace.

Why? Because the textbook remedy for a positive externality is not government ownership. The textbook remedy is to offer a subsidy equal in size to the externality - then leave the market alone.

The textbook remedy for a negative externality, similarly, is not government regulation. The textbook remedy is to impose a tax equal in size to the externality - then leave the market alone.

Now notice: Real-world governments almost never handle externalities in this manner. Not even close! Government ownership is ubiquitous, but government subsidies are only a tiny share of GDP. Government regulation - plus full-blown prohibition - is ubiquitous, but taxes on goods with negative externalities are only a tiny share of government revenue. And we almost never see governments offer a subsidy or impose a tax, then say “Our job is done.” Sure, we’ve got a gas tax, but governments combine it with carpool restrictions, CAFE standards, annual inspections, ethanol mandates, and much more.

What’s going on? In practice, the concepts of positive and negative externalities are only a smokescreen for the grossly inefficient policies governments habitually favor.

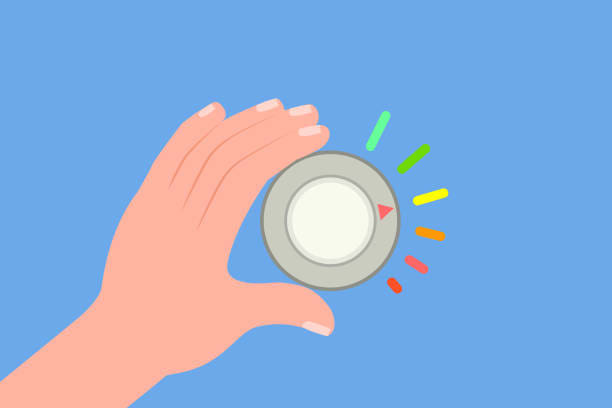

Imagine your stereo has a volume control. Call it Pigou’s Dial. The volume runs from 0 to 10. The standard government reaction is roughly: “Your neighbors like your music? Great. It has positive externalities, so raise the volume to 10.” Or: “Your neighbors dislike your music? Oh no. It has negative externalities, so cut the volume to zero.”

An enlightened Pigovian, however, speaks no such nonsense. Instead, he says: “How much do your neighbors like your music? A little? OK, I’ll subsidize you to turn the dial from 5 to 6.” Or: “How much do your neighbors dislike your music? Moderately? OK, I’ll tax you to turn the dial from 5 to 3.”

Followed by: “So long, have a nice day.”

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Yes, the textbook theory of market failure is a reproach to markets. But it is also a massive reproach to all real-world governments, because no earthly government remotely follows a Pigovian approach. Pigou tells us to carefully measure the externality, then set a subsidy or tax of matching size to marginally turn the dial up or down. THE END.

I find this criticism not so good in general, because there are many externalities and "measuring" them means nothing. To some extent an externality is simply "what the market does not measure for us", so Pigovianism is more a framework than a theory.

On the other hand, the lack of Pigovian taxes on carbon (the canonical case where the framework is almost a theory by itself) and the incredible roundabouts to avoid the simple and well known solution proves the utter disgrace that are our social systems.

Thanks, Arturo.

Right, quantifying the externalities is challenging. Privatisation of public goods makes the market measure more for us. Instead of setting up regulations to prevent overfishing, the oceans could be privatised, and then the companies owning them would have an incentive to prevent the collapse of fish stocks (otherwise, they would go out of fish, and therefore would no longer be able to charge fishing companies).

I think global warming may well be beneficial in many regions. However, at least for countries wanting to decrease it, I suppose taxing CO2eq would make sense. One challenge is that people with lower income may spend relatively more on energy, so they would be relatively more affected by the higher energy prices resulting from taxing CO2eq, altghough this could be mitigated by disproportionally directing the tax revenue to such people. Another challenge is that countries taxing CO2eq would start importing more energy from countries that do not tax it.

"Instead of setting up regulations to prevent overfishing, the oceans could be privatised, and then the companies owning them would have an incentive to prevent the collapse of fish stocks"

If you do not put physical barriers, fish would move across different properties, making overfishing profitable anyway. It is like two "private" oil fields over the same oil reservoir.

"I think global warming may well be beneficial in many regions. However, at least for countries wanting to decrease it, I suppose taxing CO2eq would make sense".

It is the canonical case for an immediate Pigovian tax: the externality is global, uniform, circulates in the atomosfere... Regarding imports, you can charge a carbon tariff.

Profitable for who? I am thinking companies owning some waters would charge fishing companies proportionally to how much they capture in their waters. Overfishing would eventually lead to no fish being captured in their areas, and therefore no revenue from fishing.

The increase in the death from non-optimal temperature is not uniform.

If fish move across properties, your own overfishing affects fish density in neighbouring properties. It is like two oil wells extracting from a common reservoir. Of course, both "privatization" and "Coasian bargaining" are better than Pigouvian taxation, but none of this mechanism is necessarily available.

I remind you the entire sequence:

Now, a funny thing is that on one side you complain on the lack of Pigouvian mechanisms, and then even for the canonical case of the carbon tax, soon you find arguments against it (!). Yes, of course, the total value of the externality is the world average impact of carbon emissions: there are winners and losers. The consensus based on detailed simulation is that the global externality of an additional molecule of CO2 is negative (at least given the current location of human population: given how costly and destabilising is large human reallocation, better not to remove that hypothesis).