TL;DR: To align AI with human values, we need to model two elusive elements: how much each being matters (moral weight) and how good or bad their experiences are (valence). But both are hard to define. People often act in ways that contradict what they believe is right.

This post distinguishes between:

- Ideal moral weights: what people genuinely believe is morally correct;

- Real moral weights: what their behavior actually reflects.

Because valence is also subjective and uncertain, we can’t measure it directly. Instead, we propose a practical method: using structured pairwise comparisons and community feedback to iteratively calibrate both w and v. Over time, this narrows the gap between ideals and actions — and offers a foundation for AI systems that reflect our evolving ethics, not just our habits.

1. Why Moral Weights Are So Difficult

Imagine you're designing a system that has to choose between preventing suffering for a crow, a cow, a human or a digital mind. How do you compare their importance?

That question lives inside the concept of moral weight: how much ethical value we assign to different beings.

But here’s the catch: even if you have strong moral principles, your actual behavior may not reflect them.

- You may believe farmed animals deserve protection.

- But you might still buy cheap chicken without thinking.

This gap isn’t just personal inconsistency. It’s a systematic divergence between:

- Ideal moral weights (w_ideal): what we genuinely believe we ought to value (based on our ethics) — not just what we say out loud. This may differ from stated values, which can reflect social desirability more than true belief.

- Real moral weights (w_real): what our actions actually reveal.

This is called the Value–Action Gap. And it's everywhere.

Most AI alignment efforts don’t fully address this. But if we want aligned AI to reflect our best values, we have to acknowledge that both versions of moral weights exist — and that alignment must help close the gap.

2. Valence: Measuring the Unmeasurable

If moral weight is about who matters, valence is about how much it matters in each moment.

Valence is the felt quality of an experience — how good or bad it is for the subject.

But unlike blood pressure or temperature, valence has no objective unit. We can’t open a brain and read off a number for suffering. And we definitely can’t compare a human’s fear with a shrimp’s pain.

Even within humans, subjective experiences vary wildly and inferring them from the outside is notoriously hard:

- A child may cry in despair over not getting a piece of candy.

- An adult might face bankruptcy with calm resignation.

So how do we even start comparing?

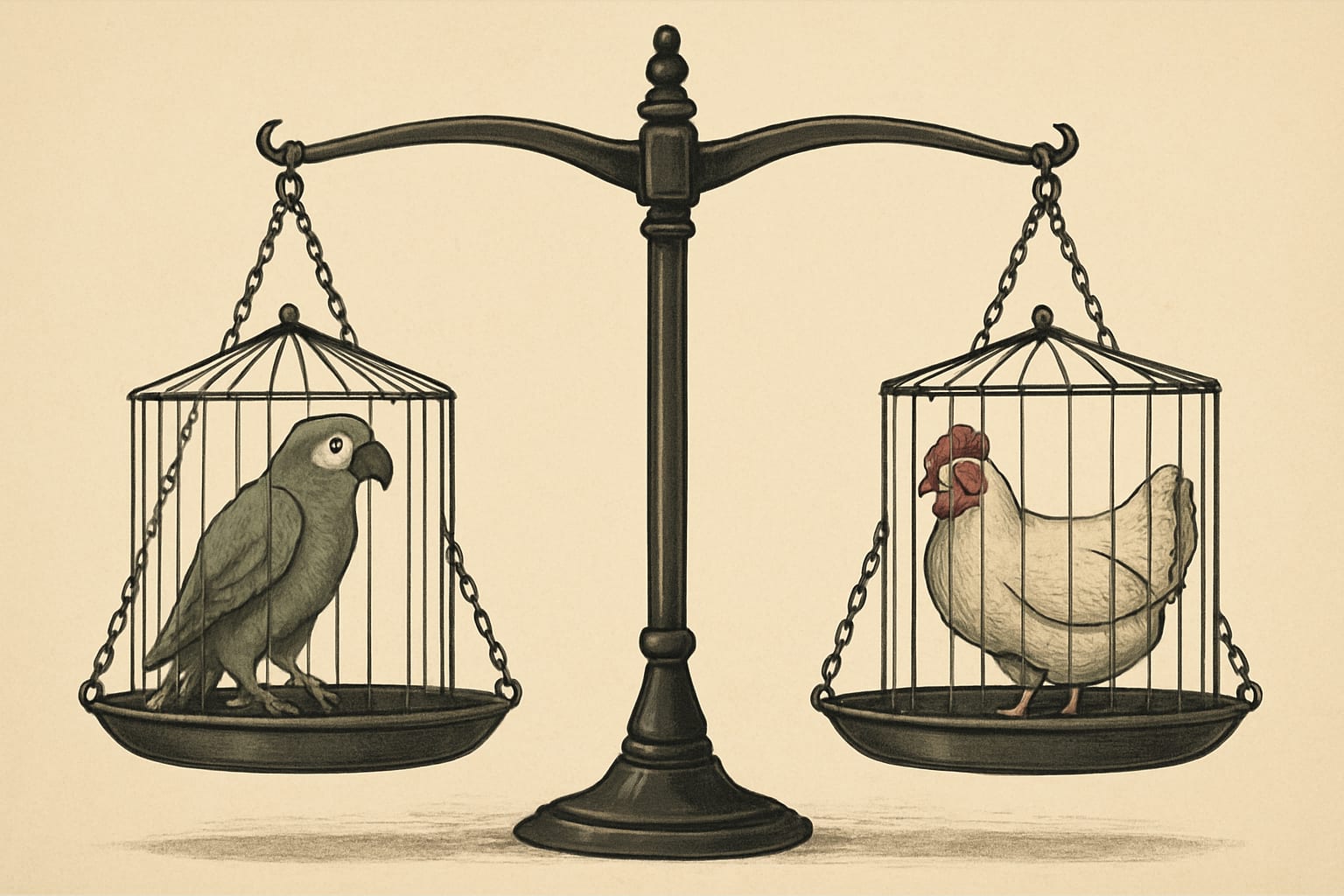

A better question: Which is worse?

Instead of inventing units, we can ask people to compare pairs of experiences:

Which seems more negative:

— A parrot kept in social isolation for a week?

— A chicken confined to a tight cage for the same period?

This kind of comparison is natural, intuitive, and repeatable. And when thousands of people answer these questions, we can use mathematical models (like Bradley–Terry) to infer relative valence scales.

The result isn’t a final answer. But it gives us a shared moral map that is better than guessing—and far better than pretending all suffering is equal or incomparable.

3. From Simple Seeds to Shared Moral Trees

Before asking everyone to compare everything, we need a structured place to begin. Ideally, this first step should be simple, intuitive, and easy to verify. We need something that doesn't rely on deep philosophical assumptions but still provides meaningful differentiation.

Here’s one way to do that:

We can imagine a basic hierarchy of fulfilled capacities and frustrated desires, grouped into five levels:

- Level 1 (L1): Homeostasis — Nutrition, Water, Respiration

- Level 2 (L2): Physical Comfort — Rest, Sleep, Pain Avoidance

- Level 3 (L3): Basic Agency — Locomotion, Posture Choice, Tool Use

- Level 4 (L4): Social & Cognitive — Social Interaction, Exploration, Learning

- Level 5 (L5): Complex Agency — Reproductive Care, Environment Shaping, Creativity, Self-Expression

For any being (cow, crow, chatbot), we check which of these categories it plausibly expresses. Then we calculate moral weights under different ethical perspectives, such as:

- Harm-Prioritarian: focuses on the ability to suffer at Level 2

- Capability-Richness: emphasizes higher cognitive and social abilities

- Equal Consideration: gives equal value once a basic threshold is met

The result is not a single number, but a pluralistic range of seed weights. These serve as our moral "scaffolding"—a stable platform for further refinement. We call this method the Frustration-Based Profiling approach: it's not based on any existing academic taxonomy but created here as an illustrative and testable framework. Different philosophical lenses—such as utilitarian, hedonistic, or capability-based ethics—can be applied to interpret the moral significance of each level. This allows the model to stay flexible while remaining grounded in observable traits.

4. Refining the Weights: Human Feedback Over Time

Once we have a shared starting point, we open it up to structured refinement.

This works through iterative community calibration:

- People review sample weights (e.g. cow = 0.3, crow = 0.25)

- They adjust these based on their own moral beliefs and how confident they feel.

- Their input updates two things:

- w_ideal: what they aspire to value

- w_real: what their choices currently reflect

Over time, we build a dynamic map of moral weights that:

- reflects both ethical reasoning and real behavior

- changes as knowledge and attitudes evolve

- avoids locking in early assumptions too rigidly

This map can guide policy, AI systems, and personal reflection alike.

Conclusion: Why This Matters for AI Alignment

Most alignment plans ask: How do we get AI to do what we want?

But we rarely ask: What exactly do we want—and how confident are we? That’s the essence of Ethical Alignment.

To build trustworthy AI systems, we need more than just aspirations. We need to monitor the gap between our ideal values and our actual behavior—and ensure that striving toward ideal morality doesn’t come at the cost of neglecting foundational moral concerns.

A system that optimizes for lofty values but ignores basic dignity or welfare may end up doing harm in the name of good. Likewise, an unexamined gap between ideal moral weights and real moral weights can grow so large that alignment becomes meaningless or self-defeating.

This approach—iterative calibration of moral weights—serves as a form of moral scaffolding. It helps us mature our ethics gradually, transparently, and in a way that AI systems can support, not subvert. It also offers a path to resolving structural alignment challenges like those raised in the 'Bad Parent' problem and the Power–Ethics Gap.

It’s not a perfect solution. But it’s a practical one: a path from intuition to structure, from contradiction to clarity, and from moral noise to navigable signal and of course, this system can change and improve over time.

Key Concepts

- Moral weight (w): how much value we assign to different beings.

- Valence (v): how good or bad an experience feels.

- w_ideal: the moral weights we genuinely believe we ought to follow — even if we don't always act on them.

- w_real: the moral weights revealed by our actual choices and actions..

- Value–Action Gap: the difference between w_ideal and w_real.

- Pairwise comparison: judging which of two cases is worse.

- Iterative calibration: refining shared values over time through collective input.

Questions for readers

- Have you ever noticed a gap between what you believe morally and how you act?

- What kind of experiences do you find hardest to compare?

Would you want to contribute to a shared system of ethical weights?

@Beyond Singularity Another issue is how you calculate positive vs negative valence. David Pearce thinks ethics is only about reducing negative experiences, and although it is good to make beings have more positive ones, it is not within ethics. So his view is, I think, the more extreme side of negative utilitarianism.

I think positive experiences are within the ethical realm, and although reducing suffering is more important than increasing happiness, I would still try calculate how much beings are happy as well and how to optimize that.

Thanks, I agree — positive experiences matter morally too. I didn’t emphasize it explicitly, but the text defines valence as “how good or bad an experience feels”, so both sides are included.

Since there’s no consensus on how to weigh suffering vs happiness, I think the relative weight between them should itself come from feedback — like through pairwise comparisons and aggregation of moral intuitions across perspectives.

Very good post.

Any rational understanding of human ethics must include the differences between the rational and emotional perception of morally evaluable facts by the human agent. An artificial mind might assess this inconsistency as invalidating the moral mandate, when it does not, so it must be informed of the peculiarities of human social behavior in this regard.

The evolutionary factor should be added: moral evolution, within the framework of cultural evolution, can and should create psychological mechanisms to gradually shorten the gap between the ideal and the real.

Thank you.

You're absolutely right: an artificial mind trained on our contradictory behavior could easily infer that our moral declarations lack credibility or consistency — and that would be a dangerous misinterpretation.

That’s why I believe it's essential to explicitly model this gap — not to excuse it, but to teach systems to expect it, interpret it correctly, and even assist in gradually reducing it.

I fully agree that moral evolution is a central part of the solution. But perhaps the gap itself isn’t just a flaw — it may be part of the mechanism. It seems likely that human ethics will continue to evolve like a staircase: once our real moral weights catch up to the current ideal, we move the ideal further. The tension remains — but so does the direction of progress.

In that sense, alignment isn't just about closing the gap — it’s about keeping the ladder intact, so that both humanity and AI can keep climbing.