Acknowledgments: Tom Marty, Vanessa Sarre, Clare Diane Harris and Jack Koch contributed to the design of the survey, Jack Koch also carried out outreach to patient support groups, and Magdalena Kolczyńska, Jordan Clist and Michael Smith contributed to the analysis of the raw data. We sincerely thank every individual who took the time to respond to the survey and reflect on their own suffering.

Summary

- Existing wellbeing metrics, including the DALY and measures of improved life satisfaction such as the WELLBY, do not directly measure suffering – a key determinant of wellbeing – and suffering metrics can address this limitation.

- A pilot survey we conducted with 485 respondents generated retrospective estimates of suffering duration and intensity for a range of conditions and life experiences over one-year periods, as well as momentary wellbeing assessments on 0-10 scales.

- While retrospective estimates almost certainly overstated many durations, they also captured extreme suffering that may have been underrepresented in real-time evaluations.

- Even common conditions, such as tinnitus and loneliness, can cause suffering that is evaluated as extreme, and the results suggest that several other cause areas may deserve greater attention due to the intensity of the suffering.

- As a next step, a larger study on a more diverse population, with adjustments to the questions to focus on shorter retrospective evaluations and reduce cognitive load, would provide statistically representative suffering assessments for a much wider range of conditions. These metrics could contribute to cause prioritisation, policy-setting and the tracking of outcomes over time.

The need for suffering metrics

Suffering is one of the main determinants of hedonic wellbeing or utility, and can be considered a direct form of disvalue. Most ethical frameworks assign importance to the prevention and alleviation of suffering, which is also an essential aspect of trying to ensure a flourishing future. Being able to measure suffering is therefore important for setting priorities for intervention, based on the key parameters of intensity, duration and number of instances. While qualitatively very different experiences can cause suffering, e.g. the excruciating physical pain of a cluster headache attack compared with grief over the loss of a loved one, the common dimension, of greatest ethical relevance, is their unpleasantness and their aversiveness – the desire to be rid of the experience. This makes them all potentially comparable on a single scale.

The most commonly used wellbeing metrics, including the QALY, DALY and the more recently introduced WELLBY, while useful for comparisons across countries and situations, and for measuring improvements that may be associated with reduced suffering, do not directly measure suffering. A Lancet paper from 2018 on global access to morphine proposed the SALY (Suffering-Intensity-Adjusted Life Year) as a measure, modelled on the DALY. As Years of Life Lost do not directly contribute to suffering, the SALY could arguably be reduced to YLS (Years Lived with Suffering). I have proposed additional suffering metrics that are more granular and focused on more intense suffering, to reduce the problem of aggregating very dissimilar intensities and ensure that severe and extreme suffering are not overlooked: YLSS (Years Lived with Severe Suffering) for suffering at 7 and above on a 0-10 scale, and DLES (Days Lived with Extreme Suffering), for suffering at 9 and above, the latter with a time unit that reflects the significance of even short durations at extreme severity. These metrics have been used in an EA Forum post by Alfredo Parra on the global burden of cluster headaches and a subsequent journal article.

At OPIS we’ve been working on creating a numerical overview of global suffering of all sentient beings, categorised by cause. The most straightforward way of assessing suffering in humans, as for other measures of wellbeing, is through self-reporting on a 0-10 scale – with the important caveat that people may interpret the numbers differently, especially the significance of the top end of the suffering scale, depending on their past experiences. The most reliable assessment is momentary suffering in real time, but for assessing durations of suffering of different intensities over a given time period, and for comparing the intensities of suffering due to different experiences of the same person, it is much simpler to use retrospective estimates.

Non-human animal suffering could potentially also be quantified using the same scale, even though the methodology would be indirect, such as behavioural and physiological patterns as well as estimates by human observers. This would allow a more comprehensive overview of global suffering.

Pilot suffering survey

In order to directly gather data on human suffering caused by various conditions and situations, as part of the planned larger overview of suffering, we carried out an online survey from September 2024 to March 2025, communicated mainly by email and social media, including through some patient support and Reddit groups. The survey, using Google Forms for ease of use, gathered both momentary measures of wellbeing and retrospective estimates of the duration of suffering at different intensity ranges for over 110 diseases, conditions and experiences, in some cases grouped as categories, with the possibility to add conditions not listed. The main goal was to determine average durations of different intensities of suffering over the course of a year for each condition, and potentially to derive reliable global YLSS and DLES figures for many of these conditions. Respondents provided information on:

- All conditions they had ever experienced that caused them significant suffering.

- Momentary measures of wellbeing on a scale of 0-10 for suffering (with 10 defined as “worst suffering imaginable, literally unbearable”), physical pain, happiness (in the narrow sense of positive emotions, i.e. positive affect), and life satisfaction.

- For 1-3 conditions selected by respondents as causing some of the worst suffering they had experienced, retrospective estimates of duration of suffering over a one-year period at different intensity ranges: 4-10 (moderate and worse), 7-10 (severe and worse) and 9-10 (extreme). These duration ranges were nested to reduce respondents’ cognitive load and increase the logical consistency of responses.

- We also collected some additional multiple-choice answers (e.g. nature of the suffering – physical pain, other physical symptoms and/or psychological suffering – and whether they were currently suffering from the condition, including "right now and this very moment") and some longer text answers providing more detailed descriptions of their conditions, and any measures they found helpful.

We obtained a total of 485 responses to the survey, yielding 595 condition selections providing usable intensity and duration data (durations provided for all intensity ranges, all consistent with each other). While the number of respondents was not large enough to obtain narrow confidence intervals for most of the conditions listed, we were able to draw a number of conclusions and learn what improvements to make in a larger, next iteration.

The survey was not intended to gauge the prevalence of conditions in the population – such data exist elsewhere, such as the Global Burden of Disease database. We specifically targeted some patient and support groups to find respondents with less common conditions, leading to some conditions being overrepresented, and respondents were in other ways not randomly selected from the population. As an illustration, the average momentary life satisfaction score among the 485 respondents was 4.8/10, well below the average for OECD countries (where most respondents were located) of 6.7/10. Furthermore, those who selected a condition to provide information on, whether or not they came from a support group, would have experienced more intense forms of the condition. For conditions with very different severities, the intensity and duration data we collected may therefore not represent the average person with the condition, but they better capture some of the worst suffering that condition can cause. In addition, we were able to compare the number of times a condition was selected with the number of mentions of it ever having been experienced, providing a rough means to estimate the fraction suffering at high severity.

Findings

Psychological suffering most commonly experienced

Among the 485 respondents, the 4 most commonly mentioned sources of suffering ever experienced were primarily psychological: depression (due to any other causes, other than those listed; 302 respondents), existential worries (287), low self-esteem/low self-worth (272) and loneliness (230). Also frequently experienced were bullying as a child (196) and child abuse by parents (123).

Conditions most & least frequently selected as “major source of suffering” among those ever experienced

Some of the conditions that had ever been experienced had a particularly high likelihood of being further selected as the 1-3 causing the most suffering, to provide further data on. Aside from physically painful conditions like cluster headaches (49/80, 61%), trigeminal neuralgia (15/28, 54%) and endometriosis (12/30, 40%), where many respondents came from support groups we had contacted and we expected higher selection rates, we also saw high selection rates for child abuse by parents (35/123, 28%), depression (79/302, 26%), PTSD (28/135, 21%; a few came from a Reddit group for torture survivors) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS/ME) (13/69, 19%), as well as others where the sample sizes were lower. Given how painful cluster headaches are, it is likely that many or most who mentioned having experienced them but did not select them as a main source of suffering had not been formally diagnosed and mislabelled their condition. This issue is probably also true for a few other conditions in the survey. A next iteration should include a question about medical diagnoses, where relevant.

On the other hand, a range of painful situations that had been experienced, including some kinds of accidents and physical assaults, were selected by few or none as among those causing the most suffering, including for example burns (0/160), bicycle or motorbike accident (0/74), fall (1/109), broken bones (3/109), assault with a firearm or a sharp object (0/30), self-harm (0/113), dog bite (0/56), and bullet ant or similarly painful insect sting, Irukandji jellyfish sting or stonefish sting (0/30). Even of the 18 who mentioned having experienced solitary confinement in prison – considered tantamount to torture when experienced over extended periods – none selected it as a major source of suffering to provide more information on, perhaps because the duration was never long enough to generate severe suffering.

Descriptions

Trigger warning: This section contains descriptions of extreme suffering that may be difficult to read – exercise self-care if needed.

The following excerpts from some of the respondents’ descriptions of their suffering provide a stronger sense of what they actually experience – the territory that the numerical map is meant to represent:

- Bulimia and low self-esteem with the suffering attributed to heavy emotional abuse by their parents: “The worse suffering has been psychological (worse than any kind of physical pain, disease or intense sleep deprivation). It is a feeling of total emptiness, of anguish, a feeling that I don't matter, that I don't even exist.”

- Anxiety disorder: “I am always anxious….I am always moving some part of my body, I think I am always living the worst case scenario and it doesn’t let me sleep at night. This is due to when I was constantly raped as a child….”

- Bipolar disorder: “Much of the time it feels like torture just to exist.”

- Bipolar disorder: “The mental pain of depression is sharp and deep. It hurts worse than even the worst physical pain I ever experienced.”

- Bullying as a child from someone who also has cluster headaches: “It was difficult to decide should this or cluster headaches be first. I think bullying that lasted almost the whole school time has affected [a] wide variety of my suffering later in life - perhaps even all of it, including cluster headaches.”

- Child abuse by their parents: “Child abuse is a contributing factor to my suffering from low self-worth, physical assault with a sharp weapon, rape, PTSD, depression, anxiety, alcohol addiction, homelessness and poverty.”

- Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME): “The most unbearable physical symptoms you couldn’t even imagine your body would be able to produce, having no treatment combined with having to lose almost every aspect of your life and identity while others move on with their lives causes the level of suffering that any prior event/illness in my life couldn’t even be compared to.”

- Chronic pain and a history of severe child abuse: “I developed arthritis in my lower back at an EXTREMELY young age due to frequent and violent rapes as a child.”

- Chronic pain: “The pain is extreme, and ANY movement in my body (including breathing) feels like I'm being ripped apart while acid is poured on my body. Sometimes I pass out from the pain. Opioids such as codeine provide very minor relief….I would rather chop my arm off rather than experience the pain even once more, but unfortunately the pain attacks happen 1-5 times per year.”

- Cluster headaches: “It was repeating torture-stage pain for hours every day.”

- Cluster headaches: “Chronic cluster headache and single parent to three young children so no one to care for me or my children.”

- Cluster headaches: “Severe intense pain in and around the eye and temple. Feeling of a red hot poker going through the eye and temple while twisting and trying to remove the eye.”

- Cluster headaches: “It's like the peak of a brain freeze that never ends. It feels like parts of your internal mechanisms in your face will soon pop or snap due to tension, but that release never comes and the pain always somehow raises itself. Your sense of self slips away because it’s like something has hacked your autonomic functions and your very core suddenly thinks striking your skull against a wall is logical, because the pain is so incomprehensible that it breaks your psyche.”

- Cluster headaches: “When they are on, you may not even be conscious of where you are, just screaming, terrifying people around you. When they are off, there was the mortal fear of the next time they come back and you'd rather die than go through another attack.”

- Cluster headaches: “Think of ice cream induced brain freeze. Multiply that by 1000 for 3 hours straight.”

- Conflict (inter-state and civil war) and terrorism: “I was in a bomb shelter, forty kilometers away from terrorists going door to door burning, raping, torturing, kidnapping and massacring people, and it feels like half the world commended them as freedom fighters in a legitimate resistance at the time. Agonizing grief….I am struggling with devastating empathy for the incredible suffering everyone around me is going through, fear, anxiety and worry for my friends and family directly involved….Frustration and anger at being stuck in a conflict I abhor under a government I hate and cannot trust and not seeing a way out.”

- Depression: “It's hard to describe. It's like chronic pain, but psychological.”

- Depression: “Depression has been a slow kill sucking the will to continue doing anything and unable to tell whether suffering is truly the nature of reality or if I have a mental illness. The suffering is not severe, but it leads to suicidal ideations and a general slump negativity that touches every part of life.”

- Endometriosis: “Pain so severe that it made me throw up for 2 days a month.”

- Endometriosis: “Pain severe enough to cause fainting and vomiting during flares.”

- Existential worries: ”I've directly (and indirectly) encountered a lot of instances of animal suffering, realized the world is full of unbearable suffering at each & every second. This got paired with cosmological hypotheses of an exceptionally large universe whose extent in both time & space could favor unspeakable amounts of suffering.”

- Loneliness: “Sometimes I feel so alone it’s as if my heart was breaking into billions of pieces, I'm falling into a bottomless pit and there's no hope and all I want is to be held and comforted by someone who would really care about me. The mental pain hurts physically too. My muscles are tense and start aching, I can't breathe well, I cry a lot and all my body hurts.”

- Loss of your child at any age: “Loss of my 22-year-old daughter to suicide left me with deep grief, guilt, regrets.”

- Other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TAC): “24/7 ice pick pain through my right eye with no letup for 9 years.”

- Other urinary tract disease: “Since around the age of 12 I suffered from (what was later diagnosed as) pelvic floor dysfunction that caused the pinching of nerves, that caused strong 9-10 level pain. Attacks would come and go (usually in response to sexual stimulation or arousal) and would last about half an hour. During such attacks I would be left immobilized, it would feel as if my lower body were being immolated and impaled on a rod of burning hot iron or were completely disemboweled. This anguish strongly characterized my teen years, a few times left young me suicidal, and gave me hosts of all other sorts of mental health issues. It completely ruined my sexual development.”

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): “Crying everyday for at least 6-8 hours a day for 10 years as a response to seeing what was happening to animals in labs when I was in medical school.”

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) caused by rape as a child: “Horrible depression, severe anxiety, severe dissociation. Physical pain from child abuse triggers it constantly.”

- Rape and sexual violence: “Caused constant PTSD symptoms daily, flashbacks, terror, sudden uncontrollable reactions, self-harm and suicidal thoughts, insomnia, and other stuff.”

- Seeing someone close to you suffer: “My mother was in terrible pain for quite a while…. Shortly before she died….there were also hours when she was screaming because she could no longer bear the pain (and all her life she had been exceptionally good at dealing with pain).....I just wanted it all to end, for both of us.”

- Skin condition (e.g. psoriasis): “At its worst, for decades, I had ichthyosis-like atopic dermatitis which made my life hell, not worth living.”

- Sleep disorder: “The disorder causes my sleep schedule to constantly rotate, as my biological clock day lasts more than 24 hours….So everyday I wake up a little later than the previous day, unless I don't sleep enough…..Mine also comes with insomnia, which means I tend to wake up a lot and have poor quality and very unpredictable sleep. Due to all of this, my physical health is utterly terrible, my energy levels are chaotic and my anxiety is always high whenever I have to go somewhere.”

- SUNCT/SUNA: “Severe stabbing pain in my eye, temple and left side of my head. The stabs happen every 3-10 seconds constantly. It gets worse when I lay down to sleep. I don’t sleep. I have refractory SUNCT so no medication works for me. Unbelievable pain.”

- SUNCT/SUNA: “The pain is constantly present, a 4 is a good moment for me but I have everyday, several times 10/10 pain which has been so much these last 4 years (hundreds of attacks a day).”

- Tinnitus: “Tinnitus affects me every waking moment of every day. It makes each day worse and robs the joy from any activity I once enjoyed. All I want to do is sleep since it’s unbearable to be awake.”

- Tinnitus: “Constant ringing in ears has made me desperate for peace.”

- Torture (other than by police): “Medical torture in many forms, the worst being forced administration of haloperidol. One of its side effects can be haptic hallucinations. Imagine your bones itching and wanting to tear off your skin to scratch them.”

- Torture (other than by police): “I was tortured using military style torture techniques as well as programming/conditioning from very young - late teens. These techniques caused severe/excruciating levels of mental/emotional and physical anguish and distress for many hours each day for years on end.”

- Torture (other than by police): “I was tortured in sexual, physical, psychological ways from ages 2-14. The actual torture has stopped now but I have chronic pain from it and many psychological effects that still cause major suffering for me.”

- Trigeminal neuralgia: “Excruciating nerve pain in the face triggered by almost everything including air movement - fans, breeze, air con, eating, drinking, talking, brushing teeth, smiling, laughing, singing, touch, severely limiting everyday life. Medication side effects that caused ataxia affecting mobility, fatigue, affected memory, brain fog. Social isolation, lack of understanding from others.”

- Trigeminal neuralgia: “My face electrocuting me. It comes on with no warning and sometimes with buildup that cannot be stopped.”

Duration estimates at different suffering intensities

We calculated average suffering durations at three intensity ranges and converted the latter two to YLSS and DLES, using midpoints of the duration ranges. Margins of error were relatively high because of the small sample sizes for most conditions, with depression (n=72) and cluster headache (n=45) providing more reliably representative estimates. We also calculated average momentary suffering for those respondents who selected a condition as their first one and said they were suffering from it “at this very moment”. For these same groups, we also determined how many were momentarily suffering at 9-10/10 and at 7-10/10, expressed as fractions of those who currently have the condition. The table below summarises the data for many of the conditions causing the most suffering, with a cutoff at 5 valid responses, sorted by the calculated average DLES – again, with strong caveats related to small sample sizes, as well as the selection bias for those with more severe forms of a condition.

| Condition | Mentioned as having ever experienced it (out of 485 respondents) | Selected as major source of suffering, to provide data on | Valid responses for duration | Ave. retrospective DLES/year (Days Lived with Extreme Suffering, 9-10/10) | Ave. retrospective YLSS/year (Years Lived with Severe Suffering, 7-10/10) | Ave. momentary suffering (0-10) (selected as first condition & suffering “at this very moment”) | Fraction momentarily suffering at 9-10/10 of total who currently have the condition and selected it first | Fraction momentarily suffering at 7-10/10 of total who currently have the condition and selected it first |

| SUNCT | 7 | 6 | 5 | 129 | 0.48 | 6.6 | 1/5 | 2/5 |

| Fibromyalgia | 37 | 6 | 6 | 119 | 0.56 | 6.8 | 1/5 | 2/5 |

| Tinnitus | 101 | 13 | 13 | 119 | 0.47 | 6.6 | 2/9 | 5/9 |

| Cluster headaches | 80 | 49 | 45 | 112 | 0.37 | 7.2 | 4/42 | 9/42 |

| Sleep disorder | 173 | 7 | 7 | 110 | 0.33 | 7.5 | 0/2 | 2/2 |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | 28 | 15 | 12 | 102 | 0.42 | 6.0 | 1/12 | 4/12 |

| Bipolar disorder | 24 | 8 | 6 | 101 | 0.34 | 6.0 | 1/6 | 2/6 |

| Child abuse | 123 | 35 | 30 | 99 | 0.38 | 6.4 | 2/21 | 7/21 |

| Loneliness | 230 | 11 | 9 | 90 | 0.30 | 5.0 | 0/7 | 2/7 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 26 | 6 | 6 | 86 | 0.31 | 7.0 | 0/4 | 1/4 |

| Rape and sexual violence | 97 | 13 | 10 | 83 | 0.29 | 5.5 | 1/7 | 1/7 |

| PTSD | 135 | 28 | 26 | 82 | 0.38 | 6.3 | 1/20 | 8/20 |

| Lower back pain and sciatica | 165 | 8 | 8 | 76 | 0.45 | 5.5 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| Endometriosis | 30 | 12 | 11 | 62 | 0.21 | 6.3 | 0/7 | 2/7 |

| Bullying as a child | 196 | 13 | 13 | 59 | 0.19 | 7.5 | 0/3 | 2/3 |

| Anxiety disorder | 211 | 29 | 24 | 57 | 0.27 | 4.5 | 0/19 | 3/19 |

| Chronic pain (any other kind) | 123 | 18 | 18 | 40 | 0.23 | 5.3 | 1/12 | 3/12 |

| Migraines | 161 | 25 | 22 | 35 | 0.17 | 5.2 | 3/21 | 4/21 |

| Chronic fatigue (CFS/ME) incl. Long COVID | 69 | 13 | 13 | 30 | 0.26 | 6.1 | 1/10 | 5/10 |

| Existential worries | 287 | 27 | 23 | 28 | 0.20 | 4.3 | 0/18 | 4/18 |

| Low self-esteem / self-worth | 272 | 21 | 19 | 27 | 0.09 | 2.6 | 0/8 | 1/8 |

| Depression (due to "any other cause") | 302 | 79 | 72 | 25 | 0.21 | 4.8 | 1/61 | 11/61 |

The correlations between the DLES estimates and the fractions momentarily suffering at 9-10/10 (among those who currently have the condition, selected it as the first condition and were suffering “at this moment”), and similarly for YLSS and momentary suffering at 7-10/10, were moderate (0.55 and 0.42, respectively, weighted by inverse variance to reduce the influence of small sample sizes). With larger sample sizes we might expect somewhat higher correlations, and also for the fraction of people momentarily suffering at 9-10/10 to represent a lower bound for the average fraction of total time spent at this intensity, as discussed in the next section.

Insights from a few selected conditions

Cluster headache – a deeper analysis

Cluster headache is an excruciatingly painful condition for which OPIS actively advocates access to more effective treatments. Having responses from several dozen respondents with this condition helped provide a sense of how valid the results of the survey were in general. 45 respondents with cluster headache provided valid duration information. Retrospective suffering evaluations were high, with most assessing their suffering at 9-10/10 for long parts of the year – an average of 2687 hours, or 112 DLES per person per year. The average assessed duration at the wider suffering intensity range of 7-10/10 was 3212 hours, or 0.37 YLSS per person per year. With an approximate one-year prevalence of cluster headache of ~1/2000 (and lifetime prevalence of ~1/1000; estimates vary), this would suggest ~500 million DLES per year and ~1.5 million YLSS per year.

For comparison, in his EA Forum post “Quantifying the Global Burden of Extreme Pain from Cluster Headaches”, Alfredo Parra estimated ~5 million DLES per year and ~46’000 YLSS (and somewhat lower figures in his published journal article: ~3.1 million DLES and 36’000 YLSS), with an average of ~1 DLES per person per year. These figures are ca. 2 orders of magnitude lower than those derived from our survey!

What accounts for this discrepancy? For the purpose of his analysis, which was primarily focused on severe and extreme pain, Alfredo based his calculations on the estimated pain intensity of each attack, rather than suffering intensity in general, and understandably treated pain and suffering intensity as roughly equivalent, at least at the high end of the pain scale, when using the suffering metrics. He also took into account the fact that attacks can vary in pain intensity, and that many patients have access to treatments that can reduce attack frequency. His analysis didn’t include the additional psychological suffering that cluster headache patients experience, during and outside attacks, and thus the full nature of the suffering as experienced. There’s also some inherent uncertainty in the modelling of cluster headache pain intensity over time. The large discrepancy in estimates also suggests that, in our survey, respondents generally overestimated the time spent at extreme intensities of suffering, in part because they assigned that level of suffering to large blocks of time rather than to shorter intervals of peak suffering.

To take a concrete, though simplified, scenario as an example: a patient with episodic cluster headaches (80-85% of patients) who has 3 hours of severe attacks daily for 3 months/year, without effective medical treatment, might be experiencing extreme suffering during their attacks for ~3% of the time over the course of a year, or 11 DLES/year. A patient with chronic cluster headaches (15-20% of patients) who has 3 hours of severe attacks daily every day of the year would be experiencing 45 DLES/year. The average patient would therefore experience about 17 DLES/year during their attacks as well as some degree of PTSD and/or anxiety even when not experiencing attacks. This compares with an overall figure of 112 DLES/year as calculated from our survey. This again suggests that the true average DLES value may be several times less than respondents’ retrospective estimates, but probably under an order of magnitude less. Similar considerations may apply to other conditions, but less strongly for those where the level of suffering is more stable.

We gain further insights if we look at the momentary suffering of cluster headache patients while taking our survey. Of 42 respondents who selected cluster headache as the first condition to provide information on and who still suffered from the condition, 13 said “it is causing me suffering right now at this very moment”, and their average momentary suffering intensity assessment was 7.2/10, including two who assessed it at 10/10 and two at 9/10. In other words, in this small sample, ~10% of respondents who currently suffer from cluster headache assessed their momentary suffering at 9-10/10, or extreme. We would need significantly larger sample sizes – for this and other conditions – to more accurately determine the fraction currently suffering at 9-10/10.

But it's worth noting that even those with cluster headache who said that they were suffering “at this very moment” were unlikely to be in the middle of a severe attack when filling out the survey, meaning the momentary suffering data potentially underrepresented experiences of extreme suffering. In fact, of the 485 total respondents, only one person rated their momentary physical pain at 10/10, and they didn’t suffer from cluster headache. In contrast, people with cluster headache regularly rate their pain at 10/10 (and informally even 11/10). This consideration probably applies to other very painful conditions as well, where the person may not be able to fill out a survey during a crisis.

Tinnitus

Tinnitus, an internal perception of sound when there’s no external source, is estimated to affect ~14% of the population each year. For most people it’s mainly an annoyance, but 2% of the population experience a severe form. Tinnitus is not even listed separately in the Global Burden of Disease database, but rather, mentioned in the descriptions of hearing losses of different severities. Of the 101 respondents in our survey who mentioned having experienced tinnitus, only 13 selected it as a major cause of suffering to provide information on, but they assessed their total suffering at intensity 9-10/10 at an average of 119 DLES/year. Of the 8 who selected it as the first condition to provide information on and said it was causing them suffering “right now at this very moment”, one assessed it at 10/10 and one at 9/10. These data point to the heavy suffering burden of severe tinnitus and support the need for more research into better treatments, as has been argued elsewhere.

Loneliness

Only 11 respondents selected loneliness as a major cause of suffering out of 230 who mentioned experiencing it. But the 9 who provided valid duration information on it assessed their total suffering at 90 DLES/year and 0.38 YLSS/year. Representing ~2% of all respondents, these data suggest how devastating this common life condition can be for a subset of those suffering from it.

Kidney stones

Only 3 respondents selected kidney stones out of the 33 who mentioned having experienced it, despite it being notoriously painful. All 3 reported having experienced suffering at intensity 9-10/10, though none for longer than a week. It seems that for some, even a brief period with kidney stones counts as one of their greatest sources of suffering, though the burden of this condition in terms of overall suffering duration appears to be modest.

Akathisia

Only 2 respondents selected akathisia, a condition involving severe anxiety and agitation, out of the 23 who mentioned having experienced it, but both reported extreme suffering for more than 4 months over the course of a year, with one describing it as “an intense inner agitation and feeling of horrific fear, for no external reason”. The fact that akathisia is most often caused by drugs such as anti-psychotics and SSRIs at the very least puts into question the way that these medications are used clinically and the lack of awareness of how severe the side effects can be.

Momentary wellbeing correlations

We also calculated the correlations between the different momentary measures of wellbeing in all 485 respondents:

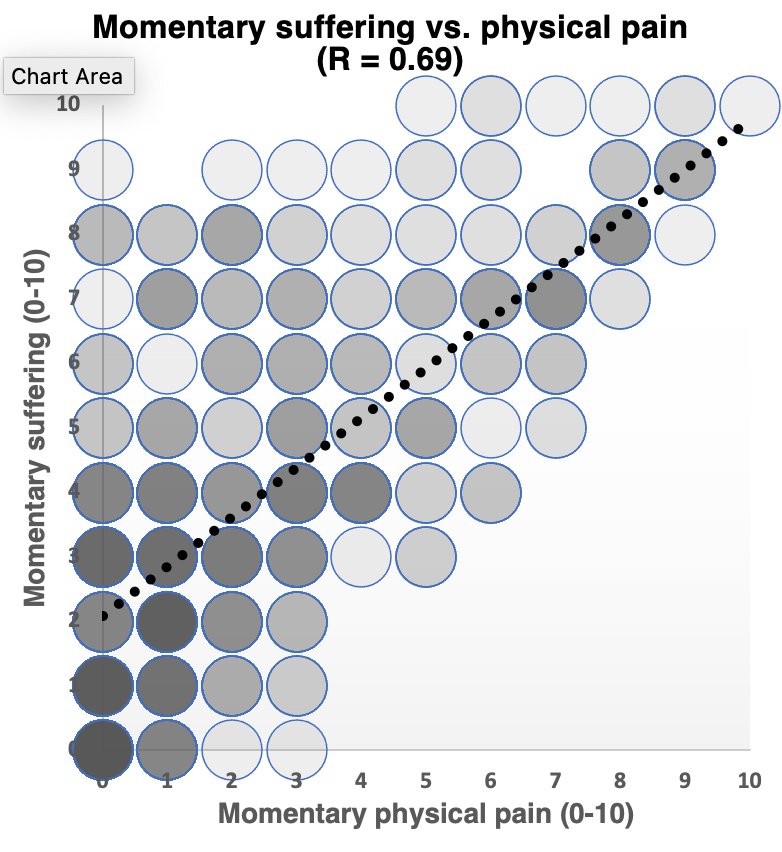

- Suffering and physical pain: R = 0.69

- Life satisfaction and happiness (positive emotions): R = 0.63

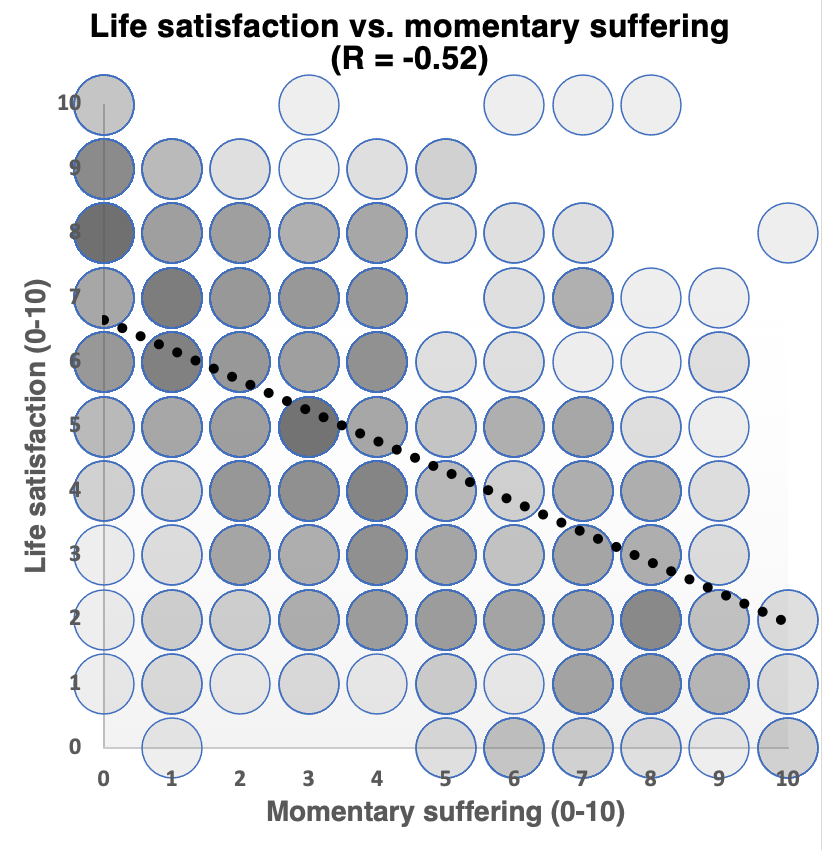

- Life satisfaction and suffering: R = -0.52

- Suffering and happiness (positive emotions): R = -0.40

- Life satisfaction and physical pain: R = -0.28

- Happiness and physical pain: R = -0.16

As we would expect, physical pain is closely tied to suffering (see graph below), yet it is distinct: some people who aren’t in any significant physical pain may report high levels of suffering due to other physical symptoms and/or psychological causes, and some who report experiencing serious physical pain report a lower numerical value for suffering intensity. However, everyone with 10/10 suffering (8 respondents in total) had at least 5/10 physical pain, and from 4/10 physical pain and up, suffering was never more than 2 intensity points lower. There are meditative approaches that some practitioners can use successfully to reduce the suffering caused by physical pain, but any such effect wasn't strongly apparent among the respondents in moderate (4-6/10) or severe (7-10/10) physical pain.

Life satisfaction and suffering were only moderately negatively correlated (see graph below), as expected from past studies on subjective wellbeing. Suffering is more of a direct experience, whereas life satisfaction is more of a cognitive evaluation and subject to a range of biases. To the extent that suffering matters for its own sake, life satisfaction doesn’t fully capture this dimension of negative wellbeing or disvalue.

Life satisfaction evaluations among people currently suffering from cluster headache did not stand out as especially low compared to those with many other conditions (5.5/10 in 42 people currently suffering from cluster headache, and 4.8/10 in the subset of 13 people suffering “at this very moment”, compared with an average for all respondents of 4.8/10). Probable reasons include the temporary nature of their physical pain as well as strong support from the patient community, from which many respondents were recruited.

Conclusions and improvements for next, larger-scale iteration

The basic premise – that people can evaluate the intensity of their own suffering – seems sound. In an effort to reduce the number of questions and potentially increase the response rate, we probably placed too much reliance on respondents’ ability to accurately remember and summate past suffering over the course of a year. On the other hand, the momentary suffering and wellbeing estimates probably do not adequately capture the most extreme suffering either. In a next iteration we would phrase the questions so that little or no explicit calculation is required by respondents, but rather, estimates of intensity and continuous duration over shorter periods (e.g. a typical day, and the past 24 hours, 7 days, or even month, for people who currently have a condition). Such retrospective assessments may help capture suffering too extreme to be adequately captured in real-time, without being subject to the same degree of recall bias.

Somewhat striking was the amount of 9-10/10 (extreme) suffering that respondents reported for several primarily psychological conditions, including some that one might intuitively associate with lower levels of suffering. The perceptions we have of the average sufferer of a condition may not reflect the experiences of those with the worst cases. Even for cluster headache and other conditions primarily associated with physical pain, evaluating only pain severity over time is insufficient for capturing the intensity and duration of suffering, and underestimates the full burden of a condition.

While physical pain can be more easily associated with one specific condition, suffering may be less so if it is the result of a convergence of life events, complicating the determination of the suffering caused by single conditions or experiences. In a next iteration we would ask about all conditions that respondents are currently suffering from, and more detailed questions to determine which one or ones are most contributing to their suffering. These questions would also help more accurately determine the percentage of people with a condition who have the most severe forms of it, as well as the suffering associate with less severe forms.

Our survey did not capture the suffering due to many conditions or experiences, including terminal cancer without adequate opioid pain relief – common in many lower-income countries, and one of the cause areas where we have been active. Also underrepresented were suffering due to armed conflict and poverty, for example, and other conditions less common among our survey population. A next iteration can better address this.

The moderate momentary life satisfaction scores of cluster headache patients, who have a condition that frequently leads to suicidal ideations, and the only moderate correlation between suffering and life satisfaction, highlight the limited usefulness of the life satisfaction measure for reflecting the intensity of suffering as actually experienced, and support the need for suffering metrics for accurately assessing suffering, which could be used alongside existing health and wellbeing metrics.

The question remains, how to standardise the top end of the scale of suffering (10/10) so that it means the same thing across the board? One approach is to better and less ambiguously define what 10/10 means. Rather than ask people to imagine the worst possible suffering that can be experienced, which may be different between people, it may be more meaningful to define it more narrowly only as “literally unbearable” – where, in principle, the will to continue living is overridden by the suffering being experienced. This still leaves open the possibility of higher numerical suffering intensities, but with 10/10 representing the threshold of unbearablesness. This approach, while still subject to interpersonal variability, at least ensures that the same ethically relevant condition is applied by all respondents.

Another, potentially complementary approach is to adjust the average suffering ratings for each condition, based on an analysis of estimates from people for more than one source of suffering they had experienced. For example, in a study on cluster headache patients cited earlier, respondents also provided pain intensity ratings for other conditions they had experienced, rating them all substantially lower than cluster headaches – including labor pain, migraines and kidney stones. This approach requires a fair amount of data to generate reliable adjustments for all conditions, and also that respondents be willing to provide similarly detailed information for more than one condition. It is also more appropriate for estimating the average suffering intensity of different conditions – analogously to the disability weights used for DALY analyses – and using them for determining the suffering burden associated with these conditions, than for assessing the suffering of any single individual, such as in a clinical setting, where adjusting their suffering self-assessment downwards may inappropriately underestimate their true level of suffering.

In a next iteration, with adjusted questions, we would like to carry out a substantially larger survey, sampling respondents across a more diverse population, to obtain statistically representative estimates for a much wider range of conditions. This expanded dataset should allow us to generate reliable global YLSS and DLES figures. Feedback and suggestions are most welcome.

Intriguing. I am not too surprised that psychological conditions can cause extreme suffering but I think the mapping of the suffering landscape here is great!

Some quick initial thoughts on how to proceed:

Re. your discussion about the top end of a scale in the third last paragraph: I generally do not like using numerical scales for things that do not have a meaningful numerical interpretation. I prefer the parts where you treat the suffering score as a categorical variable fuelled by some semi-numerical heuristic. I also like the suggestion of defining 10/10 as "literally unbearable" There is something qualitatively (and maybe morally) different about literally unbearable states, i.e. worse than death. It is also much harder to distinguish between degrees of unbearable suffering than it is to distinguish between degrees of bearable suffering, and I think it can be a good enough first approximation for now.

Other suggestions: I would also like to see the inclusion of EQ-5D-5L or some other generic health instrument and a correlation plot between the health utilities of the self-reported health states and the suffering score (even if it goes against my previously stated distaste for treating the suffering score as a numerical variable). Another thing that is a bit besides the scope of this study: A short-form question about how they bear this suffering.

Re the comparative approach in the second-last paragraph, It would also be interesting to see. It would, however, not estimate anything theoretically analogous to DALY weights unless you add some trade off-based exercise.

Thanks, Marius. Some responses:

Re: numbers vs categories: I largely agree with you. Numerical scales such as the one we used for suffering can be used intuitively to represent intensity, and the numbers can be stand-ins for categories. But problems can arise when the numbers are misinterpreted as being points on a linear scale (which it is not), or that they represent (even non-linearly) quantities of a defined unit that can simply be aggregated in various ways to yield a single value. Having separate categories of severe and extreme suffering is a way of avoiding these problems. I very much agree with the qualitative distinctness of suffering so extreme that giving up one's life is seen as preferable in that moment. For prioritisation purposes, there doesn't seem to be any need to try to distinguish between levels of unbearable suffering (as you imply) - they all deserve very high prioritisation. In principle one would never want such experiences to occur.

Re: correlating suffering and EQ-5D-5L: Yes, I agree it would be good to compare existing measures with the suffering score. EQ-5D-5L has scores for pain/discomfort and for anxiety/depression, so we would expect moderate-to-strong correlations of suffering with both, if data were collected in the same way. But for health economics, EQ-5D-5L is used especially to quantify overall utility, whereas we are arguing for separate one-dimensional suffering metrics that directly measure the key ethical parameter: experiencing an unpleasant state and wanting to be free of it. Our approach is also to try to capture extreme suffering that wouldn't necessarily be captured using momentary measures of wellbeing, such as with EQ-5D-5L. So there's a distinction not just in the scales themselves, but how they are potentially used.

Re: how they bear this suffering: We did, in fact, include such a question: "Is there anything that worked well to alleviate your suffering from this condition or situation, that you think other people should know about?" But I didn't include responses in this post, as it would have made it too long.

Re: the comparative approach: Agreed, it wouldn't be equivalent to the DALY for the reason you gave (no tradeoff exercise), just allow rankings.

Good points! Some follow-ups:

Re: bearing: I'm glad you did include something like this. Another angle would have been protective non-action factors, but your wording seems more solution-oriented.

Re: EQ-5D-5L (or something similar): I agree that the suffering and health-related quality of life or health utilities only partially overlap and that some dimensions will have more predictive power than others. What I would be interested to know is how big the discrepancy is between reported suffering and a generic instrument. Are people who suffer greatly reporting middling problems on other commonly used instruments? or How much does conventional QALY tools under-report extreme suffering? It could be another argument for why and how existing tools and metrics are inadequate.

One thing I struggle with in this area is how to think about temporal aggregation. Is one hour of suffering on two days worse than two hours of suffering one day? I am nonetheless glad to see OPIS trying to map out a 'global burden of suffering'.

Thanks so much to all the team at OPIS for this vital (and non-speculative, imagine that) work

Why do you think people who suffer so frequently and deeply rate their life satisfaction relatively highly?

(My best sense is some combination of:

Like, I can’t see a reason why wellbeing measures shouldn’t, in theory, capture these extremely negative states.

It seems like life satisfaction (a cognitive evaluation) and affect are simply different things, even if they are related, and have different correlates. It doesn't strike me as that intuitively surprising that people would often evaluate their lives positively even if they experience a lot of negative affective states, in part because people care a lot about things other than their hedonic state (EAs/hedonic utilitarians may be slightly ununusual in this respect), and partly due to various biases (e.g. self-protective and self-presentation biases) that might inclined people towards positive reports.

Do you think it’s valuable to specifically measure negative affect instead of overall affect, in this case? Or would overall affect suffice?

That's a good question. Although it somewhat depends on your purposes, there are multiple reasons why you might want to measure both separately.

Note that often affect is measured at the level of individual experiences or events, not just an overall balance. And there is evidence suggesting that negative and positive affect contribute differently to reported life satifaction. For example, germane to your earlier question, this study finds that "positive affect had strong effects on life satisfaction across the groups, whereas negative affect had weak or nonsignificant effects."

You might also be interested in measuring negative and positive affect for other reasons. For example, you might just normatively care about negative states more than symmetrical positive states, or you might have concerns about the symmetry of the measures.

Thank you!

Thanks for your answers and links, @David_Moss. The key point, as mentioned in the post and by David, is the distinction between a hedonic experience (affect) and an evaluation. But as to why people would still rate their life satisfaction at ~5/10 when they are regularly experiencing extreme suffering, I would expect that those who have learned to stay positive and look on the bright side of their life are better able to cope – to handle the pain when it happens, and to function well and experience moments of joy the rest of the time. As I mentioned, some people with cluster headaches have a strong support network within the patient community. Someone suffering alone for long periods with a severe mental illness may view their life very differently, and tell themselves a different story, than someone who is supported and encouraged by a community of fellow "warriors", even if the second person still experiences the suffering as extreme.

In terms of people also caring about other things besides their hedonic states, I would argue that people ultimately care about things because they think these will make them happy, or give their lives meaning and thereby lead to happiness. They value the happy moments they experience and tell themselves that these contribute to their life satisfaction. This doesn't negate the fact that the suffering may be literally unbearable at times.

A couple of specific responses:

-I personally don't think that "a life worth living" is all that useful as an objective concept. Most importantly, it could suggest that it's still worthwhile bringing future people and animals into existence who will experience unbearable suffering - who pass involuntarily through bottlenecks of unbearableness. The notion itself is a reflection of our biases.

-While I don't think the Cantril ladder is necessarily perceived as strictly linear, I think you're right about the distinction in that the midway point may reflect a perceived tipping point between net-positive and net-negative. Again, that's just the perception of a person evaluating their life, with their inherent biases, not a determination that filling the world with people who experience unbearable pain part of the time is a good thing.

I think the most important takeaway is not to reduce our consideration for suffering because people's life satisfaction scores could be worse, but the contrary: to treat extreme/unbearable suffering as a matter of urgency, even if people are doing their best to maintain a positive perspective.

I guess I don’t find your conclusion intuitive. I’m sure there are a range of preference questions you could ask these extreme sufferers. For example, whether they, at a 5/10 life satisfaction, would trade places with someone in a low-income country with a life satisfaction of 2/10 who does not have their condition.

My hunch is that the former is true, that there is something you can elicit from these people that isn’t being captured in the Cantril Ladder. (In my work, we’ve found the Cantril Ladder to be unreliable in other ways). But on the other side of this, I do worry about rejecting people’s own accounts of their experiences—it may literally be true that these people are somewhat happy with their lives, and that we should focus our resources on those who report that they aren’t!

I agree it would be interesting to gather specific data on such questions by asking people. A lot depends on the actual life of someone who evaluates their life satisfaction at 2/10. Do they experience a great deal of suffering, though not extreme/ unbearable? Or are they reasonably happy much of the time, but see no hope of improving their material wellbeing, especially when they see the kinds of lives people have in richer countries? 2/10 may mean different things to different people. The life satisfaction measure is just a momentary cognitive assessment, whereas strong negative affect, experienced over long durations, is in a sense more real. Trying to eliminate the very worst, literally unbearable experiences – in humans and in animals – seems to me very reasonable.

You could also ask the person with 2/10 life satisfaction whether they would agree to live in a rich country but have excruciating attacks for several hours a day for at least 2-3 months/year. And for the preferences elicited with such questions to really be meaningful, the respondent would have to know what it's really like, and to be able to compare stretches of both experiences. Brian Tomasik has referred to different utility functions of people imagining and even consenting to experience extreme suffering, and people actually experiencing it. I doubt many people would choose cluster headaches after experiencing them, regardless of the rest of their life circumstances.

In practice, of course, it isn't a binary choice anyways, and we can devote resources to improving access to effective treatment for cluster headache while trying to alleviate global poverty.

(Yep, I’m not having a go at the mission here, more at the nuances of measurement)