Summary

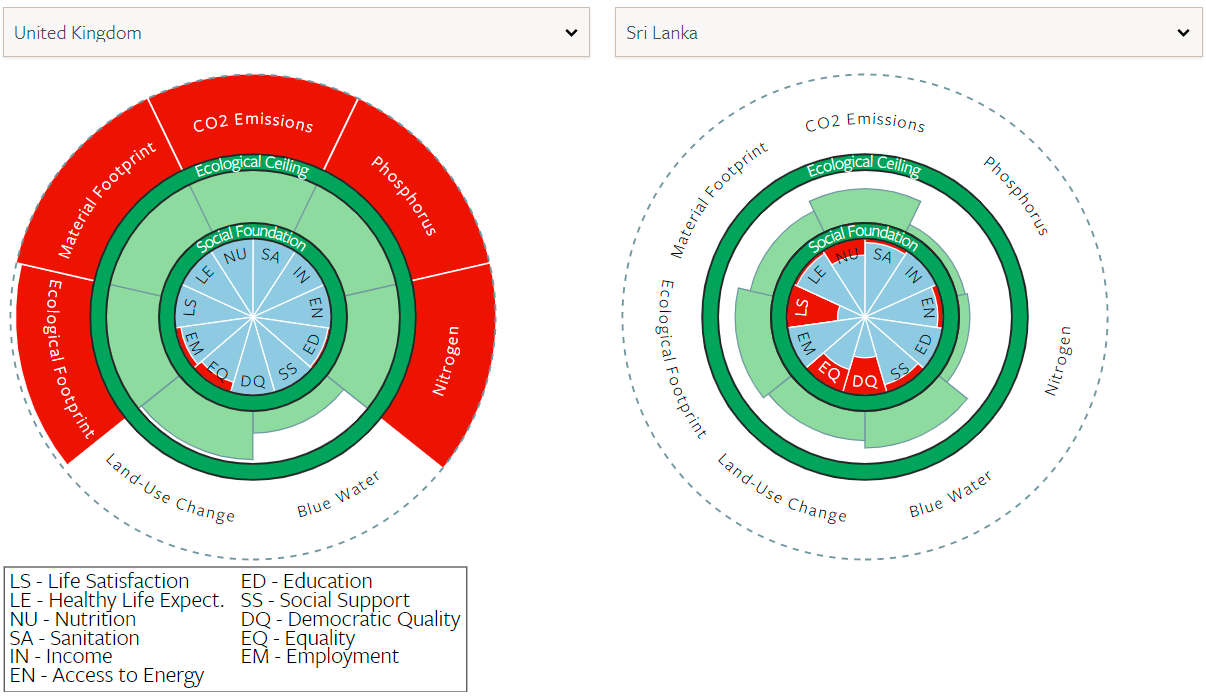

I’ve seen strong advocates of Green Growth both in- and outside the EA community but I’m skeptical: to my understanding, decoupling GDP from CO2 emissions cannot happen as fast as we need it, and decoupling GDP from resource use doesn’t seem likely. Here, I argue that in wealthy nations, we should remain GDP agnostic (be rather indifferent to it growing or shrinking) and rather focus on what matters: fulfilling social needs and improving wellbeing as well as staying within planetary boundaries and caring about ecosystems. Therefore, I name some potential policies to implement and answer some misunderstandings and counterarguments. I finish by concluding that pursuing future growth in rich countries can have devastating consequences and that we should focus on reaching a consensus about whether or not Green Growth is possible so that, if it turns out it’s not, we can pursue good alternatives and avoid collapse.

Introduction

In the EA community, I’ve come across both people who defend Green Growth and argue against Degrowth (here, here, here) as well as the opposite (by talking to people; I couldn’t find posts defending it). Here, I’d like to present my skeptical view on Green Growth and open the conversation for alternatives to the growth imperative. I’ll use the term Post-Growth to acknowledge the recognition that, on a planet of finite material resources, extractive economies and populations cannot grow indefinitely and we should therefore shrink our energy and material throughput without really caring about whether GDP grows or not (i.e., be GDP agnostic).

The question of whether Green Growth is possible is mostly about whether it’s possible to simultaneously have a growing economy while CO2 emissions and material use decline (AKA ‘absolute decoupling’).

Decoupling GDP from CO2 emissions

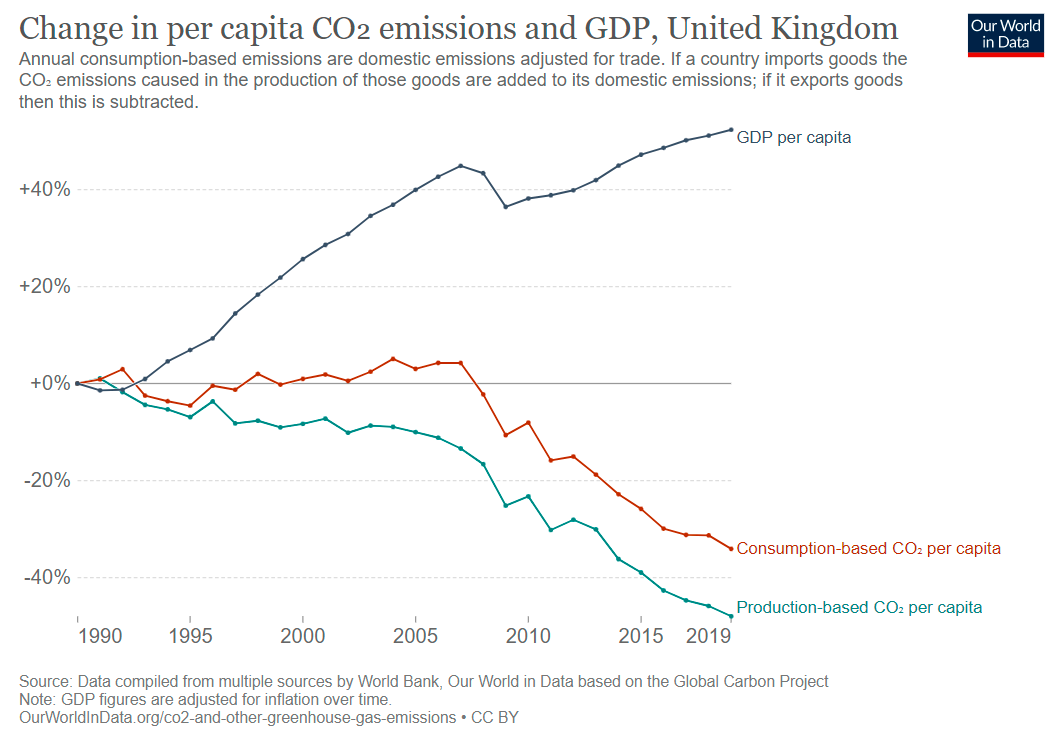

It seems that absolute decoupling between GDP and carbon emissions is possible to achieve, as it has already happened in several developed countries (in the graph below you can see how, in the UK, while GDP per capita has increased, consumption-based CO2 per capita (i.e., taking into account outsourcing of production) has decreased).

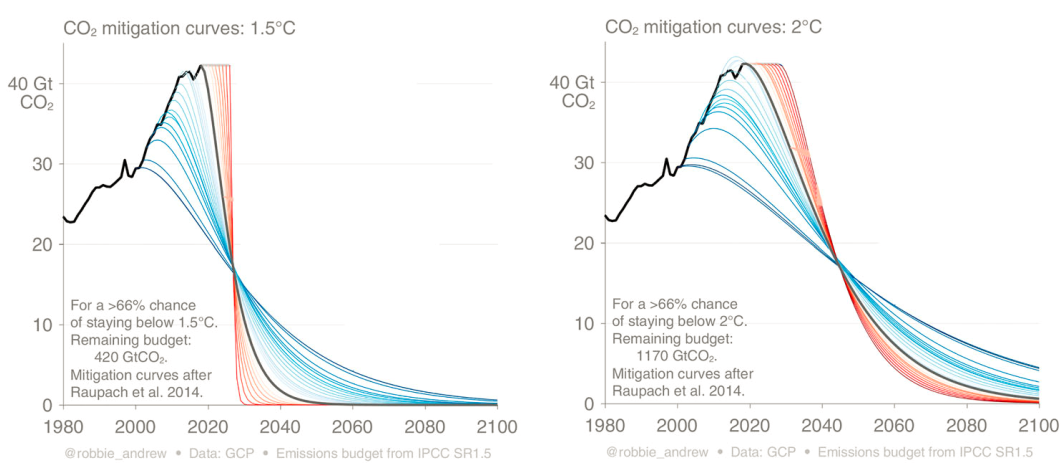

The problem is that CO2 emissions need to be reduced dramatically to stay within 1.5 or 2ºC of warming (and the pledges made in the Paris Agreement are not enough).

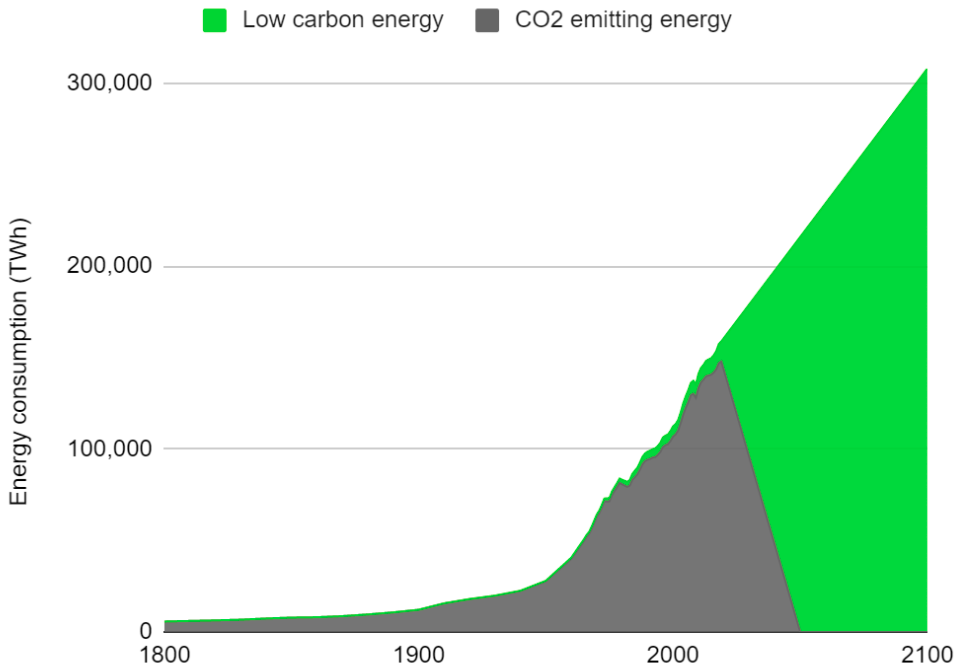

Which means that, if our transition to low-carbon energy has looked like the first part of the following graph until now, we’ll need a rather sharp transition in the near future. (see some forecasts for the transition here)

According to Hickel (I haven’t really dug into the issue myself), many proposed solutions are not as promising as they once seemed, as they’d either take too long to materialize to be of much help now, be too risky, or both. New nuclear plants would take very long to get up and running; fusion will just take too many decades; solar radiation management through aerosols injected into the stratosphere has too many side effects; and Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) has also too many side effects and reduced scope. What about renewables? A major issue here is the materials needed for building the infrastructure: resource extraction for many materials will have to increase manyfold in the next decades (especially for the lithium used in batteries). With these extraction levels, it seems we’ll run out of materials and we’ll have a lot of ecological and social problems due to overextraction: deforestation, biodiversity loss, contamination of soils and water…

A counterargument I’ve encountered is that we’ll invent new technologies that will save us (new means of energy extraction, new types of batteries, new ways of reducing solar radiation and CO2 in the atmosphere…). Maybe… but thinking that this will happen soon enough for all the areas in which we need such solutions seems too optimistic for me – forecasts showing this can happen fast enough are welcome and will cheer me up :)

So, absolute decoupling between GDP and carbon emissions seems possible but not soon enough globally to stay under 1.5 or 2ºC nor without too many negative consequences, if we continue to grow our energy demand at existing rates.

Decoupling GDP from resource use

While it’s quite obvious why we need to reduce carbon emissions, it may be necessary to first briefly justify why reducing resource use is important: because of resource scarcity and environmental degradation.

Resource Scarcity

In a planet of finite resources, we can’t continue extracting materials at the current or at a higher pace forever. The question becomes: for how long can we continue?

“The general consensus is that many of the largest and most accessible ore bodies have already been developed. Recently-discovered ore bodies tend to be smaller in size, to have lower rates of mineralization, and to be located deeper underground … [However,] new discoveries of metals and minerals have thus far kept pace with demand” (Kirsch 2020). There isn’t a specific consensus on when we’ll reach the largest production of different minerals after which it’ll decline (“peak minerals”) and there’s a shortage of quality studies regarding material scarcity, but some experts warn about sand scarcity (which has associated social problems), peak phosphorus (but see a discussion here), and shortage of other elements happening soon.

The relationship between finite resources and economic and population growth was already studied by computer simulations in 1972 in the famous report The Limits to Growth. According to Wikipedia, “The report concludes that, without substantial changes in resource consumption, “the most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity”. Although its methods and premises were heavily challenged on its publication, subsequent work to validate its forecasts continue to confirm that insufficient changes have been made since 1972 to significantly alter their nature.” Herrington (2020) modeled different scenarios and concluded that if we want to avoid decline/collapse (under their understanding of the terms), business-as-usual (i.e., pursuing economic growth) is not possible, even when paired with unprecedented technological development and adoption, and that the only solution would be a transformation of societal priorities together with technological innovations specifically aimed at furthering these new priorities.

In addition, scarcity may create or exacerbate social problems: “The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) suggests that in the last 60 years, at least 40 per cent of all intrastate conflicts have a link to natural resources” (source).

But scarcity may not be the biggest problem. Declining ore grades does “not only [increase] the costs of production but also the environmental costs of extraction, as more earth and rock need to be processed per quantity of ore recovered” (Kirsch 2020).

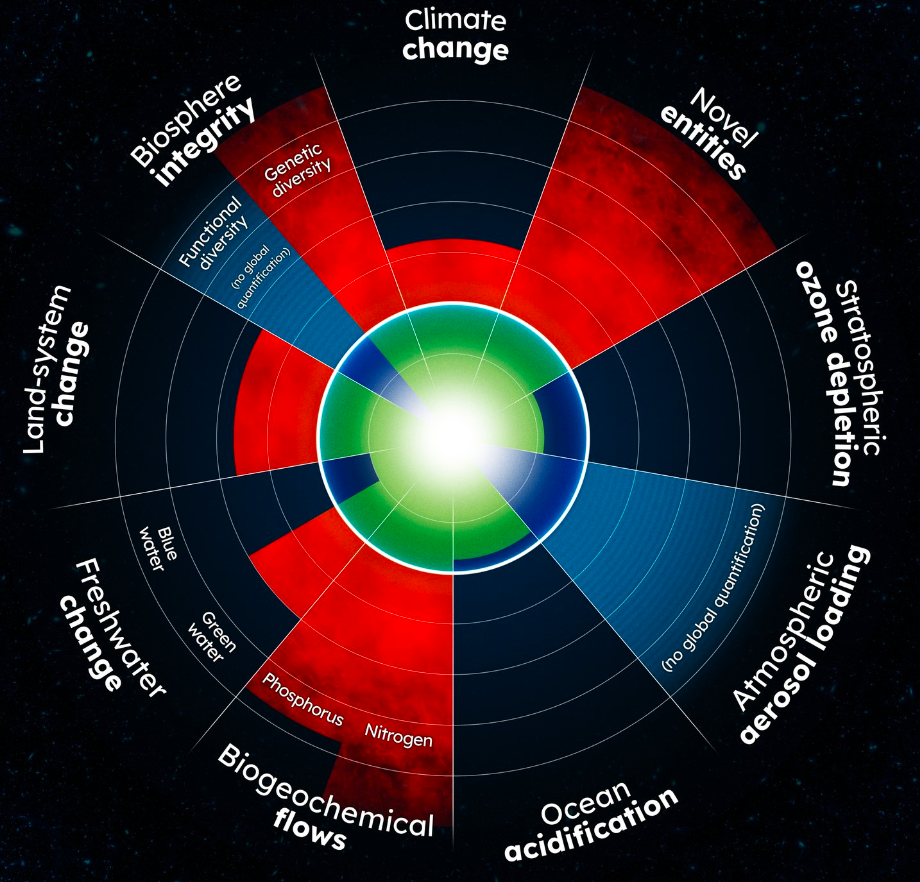

Environmental Degradation and Planetary Boundaries

While the conversation about environmental protection very often goes around climate change, this is just one out of several planetary boundaries the transgression of which “may be deleterious or even catastrophic due to the risk of crossing thresholds that will trigger non-linear, abrupt environmental change within continental-scale to planetary-scale systems" (Rockström et al., 2009). The other planetary boundaries identified are:

- Biosphere integrity: number of species going extinct every year

- Land-system change: % of land surface converted to cropland

- Freshwater use: global human consumption of water

- Biogeochemical flows: excessive nitrogen and phosphorus used as fertilizers

- Ocean acidification

- Atmospheric aerosol loading

- Stratospheric ozone depletion

- Novel entities: concentration of toxic substances, plastics, endocrine disruptors, heavy metals, and radioactive contamination in the environment

Out of the 8 (at least, partly) quantified planetary boundaries, 6 have already been crossed (at least, for one of the indicators) on a global level as of 2022, although some countries have crossed them much more than others.

Material extraction may lead to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and pollution of soils and water, among other problems. At the current levels of extraction, this is already happening too much, so it’s hard to imagine that if we continue growing our material needs, we can get back within the safe boundaries.

What if nature doesn’t have intrinsic value to me? We humans and other sentient beings are dependent on being within safe planetary boundaries (e.g., if our environment becomes polluted, our air and food are also polluted), so it seems reasonable to me that you should still care about these boundaries.

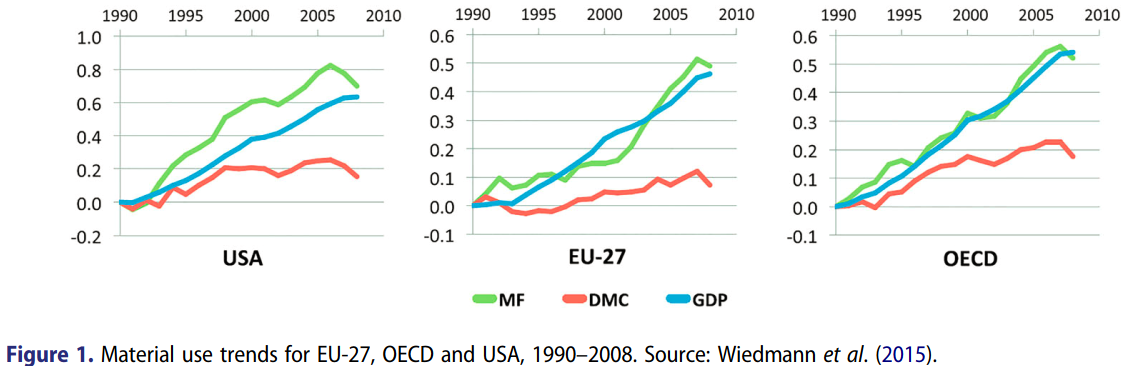

Decoupling

In contrast to the decoupling from CO2 emissions, here, historical trends show us that, even in rich countries, while GDP has gone up, Material Footprint (which accounts for all of the material resources used to produce the goods consumed in a country) has gone up at the same (or even higher) pace – so, no decoupling so far.

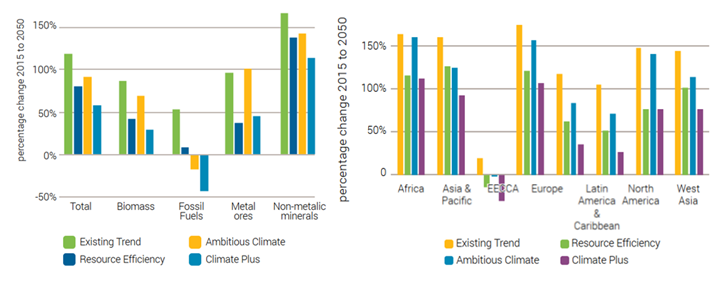

And it doesn’t seem to get better in the future by looking at the predictions made by the UN Environmental Program (UNEP). Even by assuming both increases in resource efficiency and an ambitious climate policy (which would entail a resource extraction tax and a very high tax on carbon ($573 per ton) plus rapid technological innovation supported by the government – an overly optimistic scenario assuming limiting global warming to 2ºC), resource extraction nearly doubles even in Europe and North America from 2015 to 2050.

So, it seems that absolute decoupling won’t happen. But why? Aren’t there ways to reduce Material Footprint? Let’s look at some of them:

Improving efficiency

Improving efficiency seems an obvious solution: producing goods with less material. However, there’re a few issues:

- Consumption doesn’t decrease because higher efficiency decreases prices, which leads to higher consumption (known as the rebound effect or the Jevons Paradox; see section 3.2 here for more on first-, second-, and third-order rebound effects on material and energy use)

- Physical limits and the fact that the low-hanging fruit has already been exploited: as mentioned above, due to declining ore grades, today, for many metals, about 3 times as much material needs to be moved for the same quantity of metal than a century ago. For absolute decoupling to take place in rich countries, each unit of production will need to be produced using just a fraction of its current resource inputs, and for some crucial materials, the trend just seems to go in the opposite direction.

Shifting from manufacturing to services

One could think that services seem less resource-intensive, but in reality, they aren’t, as they require much infrastructure for buildings and transportation, technology, etc. (see section 3.4 here for more on “the underestimated impact of services”). This, and the fact that people use the money earnt in services to buy material goods, may be key reasons why historical trends show no absolute decoupling in countries that have transitioned from manufacturing to services.

Circular economy

Reusing and recycling more are important strategies to implement but are by far not enough (e.g., most of the materials used cannot be recycled, as many materials are used for food and energy production, building infrastructure, or are waste from mining). Moreover, a circular economy is mostly incompatible with growth:

- Material goods would last longer, which would limit growth because we’d need to buy fewer of them

- There’d be increasing costs due to internalization, which would limit growth since it requires externalization

Cap on annual resource use and waste

This is actually a very good idea and would entail products of better quality which last longer. The issue is that for this to drive growth at 3%, products have to be 3% ‘better’ per year, which doesn’t make much sense:

- Will we really benefit from having clothes or furniture that are many times better?

- Do we want to pay many times more for products just to drive growth?

In the end, if products last much longer, we’ll consume less of them, which would limit growth.

In summary, I’m skeptical about Green Growth: absolute decoupling between GDP and CO2 emissions cannot happen fast enough, and between GDP and resource use is not possible because, despite reducing material use being possible, this would entail less GDP growth or would even reduce GDP (so, you cannot name it ‘decoupling’).

(see section 3.6 here for more on why we have “insufficient and inappropriate technological change” to achieve decoupling: “Simply put, technological progress is (1) not targeting the factors of production that matter for ecological sustainability and not leading to the type of innovations that reduce environmental pressures; (2) it is not disruptive enough as it fails to displace other undesirable technologies; and (3) it is not in itself fast enough to enable a decoupling that is absolute, global, permanent, large and fast enough.”)

A recent German survey found that “environmental protection specialists predominantly express a preference for growth-critical concepts (a-growth/post-growth and degrowth) as compared to green growth.” But do we need growth in rich countries, after all?

Do we need growth in rich countries?

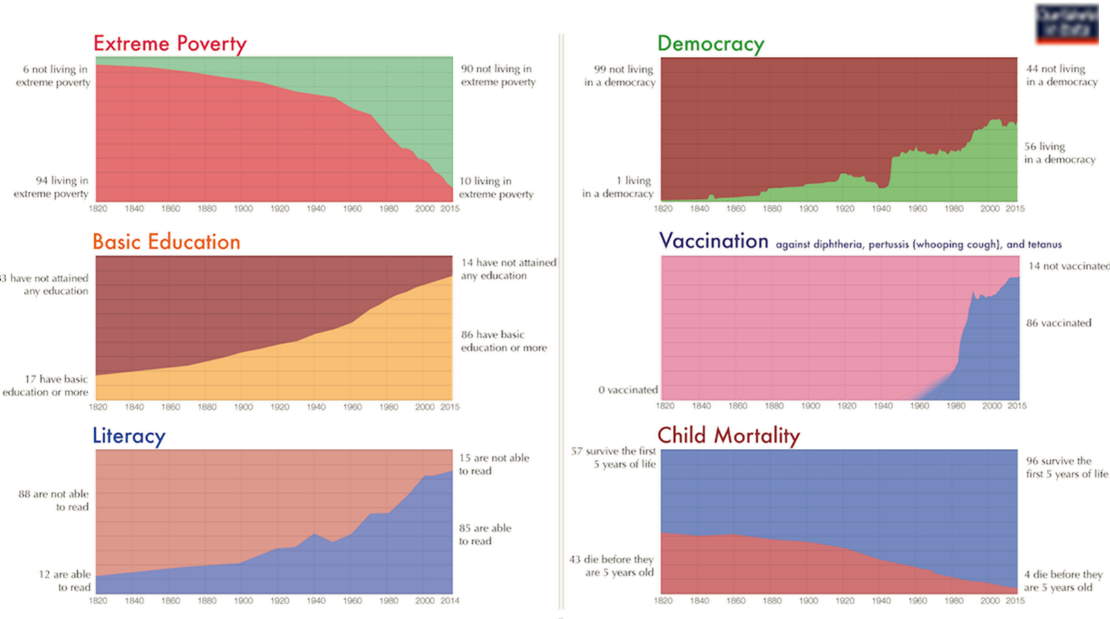

Over the past centuries, as our economy grew, we’ve seen great improvements in poverty, education, democracy, and health.

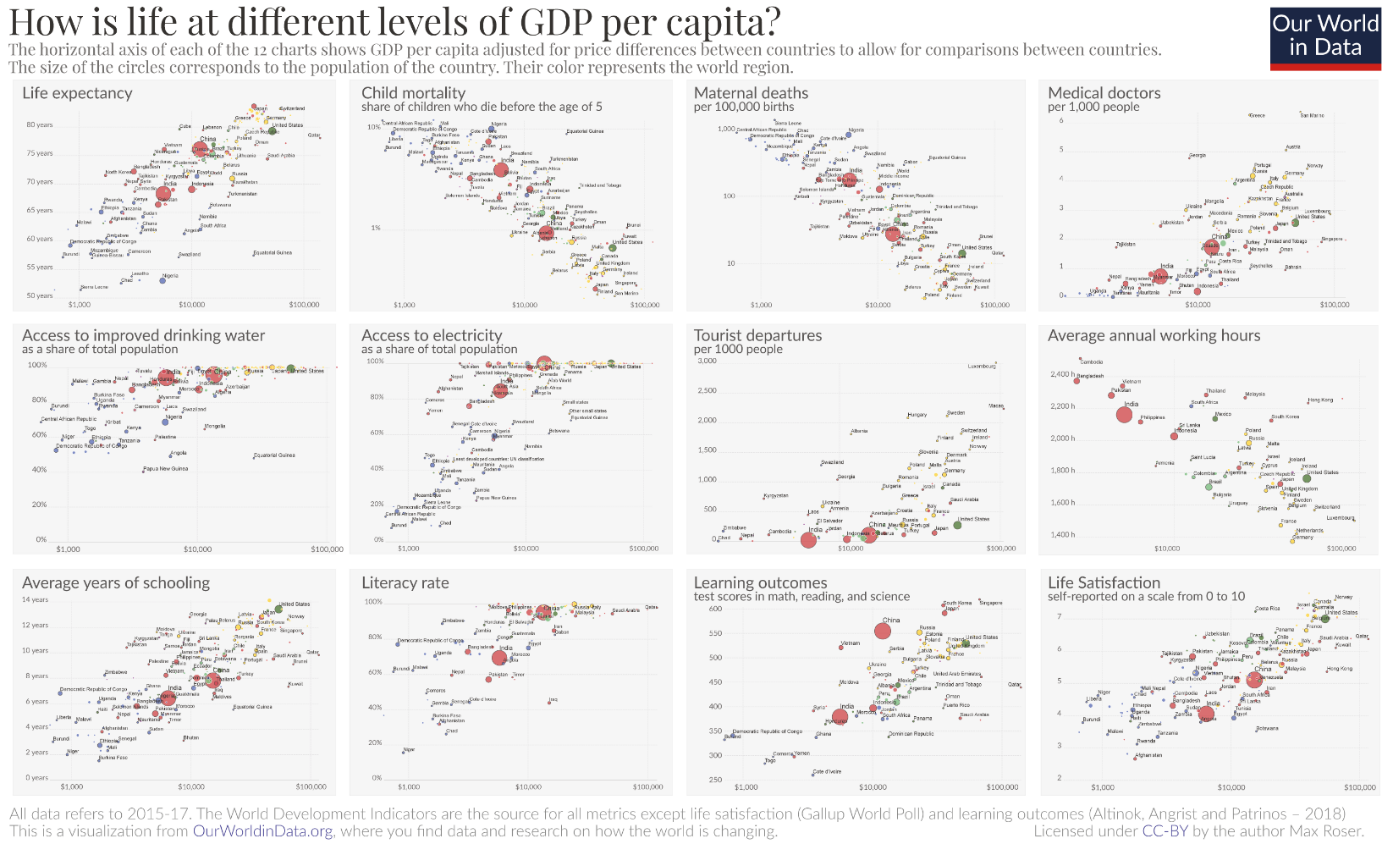

And also at present: higher GDP is correlated with better social indicators.

So, it seems that one way of improving social outcomes is having a growing economy. I guess we’d agree that underdeveloped nations need to grow economically. But what happens after the economy of a country has grown so much? Do rich countries also need to grow?

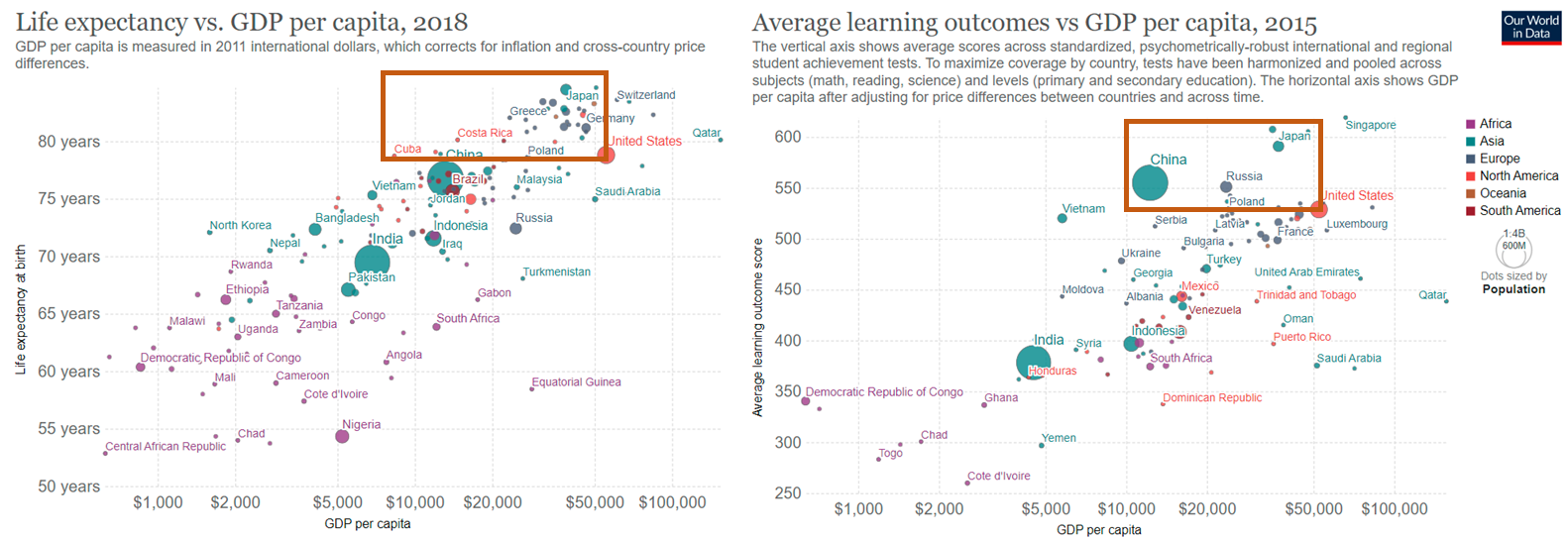

Both life expectancy and learning outcomes are better with increased GDP per capita. However, many countries have achieved a higher life expectancy than the US with a fraction of its GDP per capita (note that the x-axis is plotted logarithmically, so there’re countries in which the average citizen lives longer than the American one with half, or less, of the income). And same for education: many countries have achieved better outcomes than the US with a fraction of its GDP per capita. (Yes, comparing countries’ performance to the US’ may be cherry-picking, but the point is that it’s possible to achieve good outcomes without a big income, so let’s learn from the best performers.)

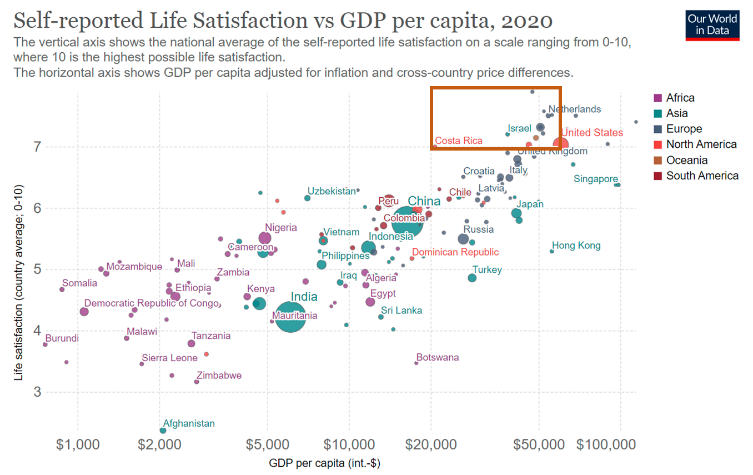

Across nations, log GDP per capita is also highly correlated with life satisfaction. But several countries have higher life satisfaction than the US with much less of its GDP per capita: Costa Rica, for instance, has similar life satisfaction than the US with 1/3 of its GDP per capita.

If what we care about is subjective wellbeing, I think we should care less about GDP (of rich nations) than the graph above could suggest (as also discussed by Michael Plant), because of three reasons:

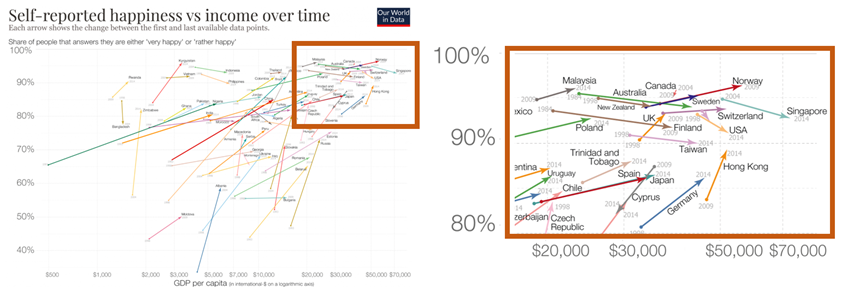

- Many rich nations, as they get richer, their share of happy people doesn’t seem to increase (but often declines) (Easterlin Paradox).

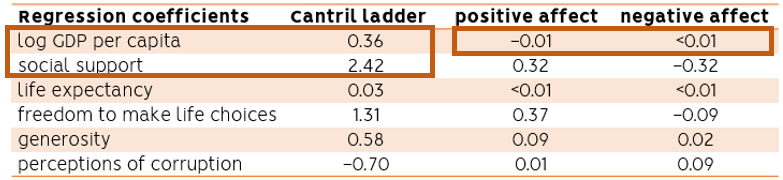

- If we take life satisfaction as measured with the Cantril ladder (an index that ranges from 0 to 10, representing the worst to the best possible life for you, respectively), GDP per capita is important but, as shown in the World Happiness Report, several other aspects have a much higher influence: both on a global level and by looking at relatively happy regions (citizens of both Nordic and Latin American countries are more satisfied with their life than predicted based on their log GDP per capita), it’s clear that what matters the most is social support and good institutions with good welfare.

- Subjective wellbeing is not just about ‘life satisfaction’: other measures of it are even less related to GDP, such as positive and negative affect (i.e., emotions experienced on a daily basis; see figure above), happiness (when people are asked "Taking all things together, how happy would you say you are?“), or how meaningful one’s life is.

So, if we want to fulfill social needs and improve subjective wellbeing, why not target these directly instead of pursuing overall growth? That’s the focus of Post-Growth/alternatives to the growth imperative.

Post-Growth/Alternatives to the Growth Imperative

In Hickel’s words (he actually uses the term “Degrowth”, but not with the connotation of reducing GDP):

It is about reducing the material and energy throughput of the economy to bring it back into balance with the living world, while distributing income and resources more fairly, liberating people from needless work, and investing in the public goods that people need to thrive. It is the first step toward a more ecological civilization. Of course, doing this may mean that GDP grows more slowly, or stops growing, or even declines. And if so, that’s okay; because GDP isn’t what matters. Under normal circumstances, this might cause a recession. But a recession is what happens when a growth-dependent economy stops growing: it’s a disaster.

We can pursue this in an organized manner to avoid disaster by:

- Scaling down throughput (i.e., the amount of material and energy flowing through the economy) by introducing taxes or caps on resource use, emissions, and waste, internalizing costs (i.e., paying the real social and environmental costs of products), ending planned obsolescence (so that products last longer), cutting advertising, or scaling down ecologically destructive industries (such as fossil fuels, intensive animal farming, airlines, arms, or single-use plastics)

- Re-distributing money on a national level (by taxing resource use, pollution, wealth, and marginal income more, increasing welfare or introducing a Universal Basic Income) as well as from rich to poor nations (e.g., by internalizing costs including paying fairer wages to producers and paying to offset the environmental impact of production, which tends to happen in the Global South)

- Abandoning GDP as a measure of progress and replacing it with a more holistic alternative including social and environmental indicators (such as the Genuine Progress Indicator), and focusing public policy on improving it

There’s much potential criticism and skepticism to the measures outlined, and I’m not expert enough to defend whether there’re good chances that these measures can be implemented without too many bad consequences. It’s a very important discussion but not the focus of this post (and as I mention below, I encourage research and debates on implementable Post-Growth strategies). The point I want to make here is that the alternatives (business-as-usual or try to pursue Green Growth) will lead us to a catastrophic recession (after all, we live in a finite planet), so to avoid it, we need a plan.

I’ve seen some criticisms of alternatives to the growth imperative (which are often based on misunderstandings), so I’d like to answer them here shortly:

- The focus is on the wrong thing, namely GDP, and shrinking it would make us worse off → As I understand it, we should remain GDP agnostic and, with well-implemented strategies (regarding more welfare/UBI, internalizing costs, focusing more on social indicators…), to me, it seems plausible that we won’t be worse off.

- If GDP shrinks, we’ll suffer just like in a recession triggered by a financial crisis or a pandemic → It’s actually the opposite: it’s planned, and it decreases only ecologically and socially destructive sectors while it increases welfare and environmental protection (and it can indeed be a measure to avoid a crisis).

- Poor nations would suffer unintended consequences because they rely heavily on exports to rich countries → In fact, poor nations will benefit from it because as we internalize costs, they’ll get a fair salary and get compensated for environmental costs.

- Massive unemployment will result from decreases in production → This can be avoided by shortening the working week, and the decrease in income (less than expected if we also redistribute money better) wouldn’t matter because we wouldn’t need to pay as much thanks to more welfare or a Universal Basic Income. (Unemployment might indeed rise in nations which rely on industrial production (e.g., garment-exporting countries) and tbh I’m not sure what strategies may work here.)

- A leave-it-to-the-market approach will bring things back to balance and solve the issue → This approach doesn’t seem to work in the current system, as products are not accurately priced by the market due to subsidies and cost externalization. In addition, planetary boundaries and natural ecosystems might collapse in a non-linear way, making it too late if we wait until we get there to act.

- The general population won’t accept these changes → If we raise awareness in the general population about the problems we’re likely to face and the alternative which may be worse (future collapse) (if that’s indeed the case, as I’m arguing here) as well as provide information about the effectiveness and implications of the proposed policies, resistance may shrink. The European Environmental Agency calls for “growth without economic growth” in a democratic manner. In addition, as we’ve seen during the pandemic and with advanced technologies taking some jobs, we have the capacity to adapt our economies, especially when facing extreme situations.

Final words & next steps

By not following the growth imperative, we aim at avoiding an ecological collapse and its associated economic collapse.

Possible outcomes of such a collapse would be:

- Disruption of ecosystem due to transgressing planetary boundaries (e.g., extinction of many species)

- Conflicts due to resource scarcity (which do happen, although I’ve been told the book Why We Fight gives arguments why this is unlikely to happen, but I haven’t read it myself)

- Forced migration due to climate change and wars

- Destruction of humanity’s long-term potential

What are the probabilities?

- It depends on how techno-optimist you are, but I consider it almost inevitable (unless we stop growing), sooner or later (since we have finite resources, infinite growth is not possible)

- We’re dependent on many resources, so the probability that one becomes too scarce and this causes trouble seems quite high

I think it’s worth paying more attention to this potential problem, and it appears to me to be relatively neglected as well (or rather, often criticized). Both in the EA community as well as outside of it there seem to be people advocating for Green Growth while others defend it’s not possible and advocate for alternatives. Ideally, we should reach a consensus about whether or not Green Growth is possible:

- How realistic are the optimistic views that technology will be able to deliver, fast enough, green energy, mitigate climate change, and bring us back under all the remaining planetary boundaries?

- How likely is it that we won’t run out of any crucial resource in the next century (thanks to new sources or new materials and technologies discovered, including asteroid mining, but also considering things that may artificially exacerbate the problem such as international conflict)? [see some discussion on this post where Robert Wiblin argues against working on resource scarcity]

- On a planet of finite resources, it doesn’t seem like we can continue growing indefinitely – Under business-as-usual, when would we reach plateau/collapse?

Do we have good forecasts for that? Why haven’t we reached a consensus yet? Would such a consensus be possible? If so, how? And after having reached a consensus, if it turns out we should advocate for being GDP agnostic rather than for growth:

- Which policies do and which do not work for fulfilling our social needs while staying within planetary boundaries?

- If GDP does (at least, temporarily) shrink, can we still fight poverty and provide welfare, or will our quality of life decrease?

- How to receive citizen support for the implementation of such policies?

- How to avoid side effects (e.g., poor nations that depend on rich ones, or some nations that continue growing getting too powerful)?

Given that, to me, Green Growth seems quite unrealistic and the stakes are high, I feel the case for alternatives to the growth imperatives is stronger than leaving it to optimistic techno-dreams. That’s why I decided to write this post to share my concerns, listen to arguments against them, and encourage EAs to work on that.

Further resources

[This section was contributed by Johannes Schubert]

To learn more about the Green Growth vs. Post-Growth/Degrowth debate:

- Decoupling Debunked: publication from the European Environmental Bureau with a detailed analysis of why a Green Growth strategy would not be an adequate response to cope with current challenges

- Social Well-Being Within Planetary Boundaries: the Precautionary Post-Growth Approach: publication from the German Environment Agency offering a fine-grained analysis of the Green Growth and Degrowth positions as well as precautionary options for reform

- The Future is Degrowth: book with a good overview of Degrowth arguments

- Exploring Economics: about different economic perspectives

- Nature Economy: about the links between nature and economics

To learn more about practical applications and ways to get involved (mainly based in Europe):

- ZOE Institute for future-fit economies: think tank that proposes concrete policies for the EU based on a broader conception of the economy

- Foundational Economy Initiative: group of researchers interested in alternatives to mainstream economics

- Economists for Future: student initiative which calls on economics to broaden its research focus and presents economic perspectives that are marginalized in traditional economics but have the potential to solve current social-ecological problems

- Several cities applying the Doughnut Economics approach (Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, Melbourne, Sydney)

- Economy for the Common Good: tools for companies (interested in) following a common good-oriented economic practice

- Transition Town movement: initiative for transformation at the community level

Thanks to Malte H, Johannes Schubert, and a couple of others (who prefer not to be named) for comments on an earlier draft of this post.

Thanks for the write-up. I upvoted because I think it lays out the arguments clearly and explains them well but I disagree with most of the arguments.

I will write most of this in more detail in a future post (some of them can already be seen here) but here are the main disagreements:

1. We can decouple way more than we currently do: more value will be created through less resource-intensive activities, e.g. software, services, etc. Absolute decoupling seems impossible but I don't think the current rate of decoupling is anywhere near the realistically achievable limits.

2. Renewables are the main bottleneck: The energy per dollar for solar has decreased exponentially over the last 10 years and there is no reason it should not continue; the same is true for lithium-ion batteries. The technology is ready (or will be within the next decade) and it seems to be mostly a question of political will to change. Once renewable energy is abundant most other problems seem to be much easier to solve, e.g. protecting biodiversity if you don't need the space for coal mines.

3. The global economy is interconnected: It is very hard, if not impossible to stop growth in developed countries but keep growth in developing countries. Degrowth in the West most likely implies decreased growth in the developing world, which I oppose.

4. More growth is required for a stable future path: Most renewable technology has been developed by rich nations. Most efficiency gains in tech have been downstream effects from R&D in rich nations. If we want to get 1000x more efficient green tech, it will likely come from rich countries that pay their scientists from public taxes. In general, many solutions to problems pointed out by degrowthers require a lot of money. A bigger pie means a bigger public R&D budget and more money to spend, e.g. on better education or national parks.

5. My vision of the future: I don't think we can scale to infinite value with finite resources. There clearly is a limit at some point but I don't think we have reached it yet. I want to strive toward a world that could host 100B inhabitants powered by solar, hydrogen and nuclear. People live in dense cities with good public transport. People mostly stopped eating meat and vegetarianism drastically reduced land use and problems of pollution. Many problems that exist in the West today are solved in the future, e.g. the infant death rate is not 0.001 (like it is today in the West) it should be 0! I just can't see why the current level of GDP is optimal for some reason and I think we should aim to grow GDP AND solve other problems (and the two are not mutually exclusive or GDP is even necessary for the other).

6. GDP growth in the west is not a major goal for EA anyway: I agree with the fact that GDP growth in already rich countries should not be a major goal for EAs. We should aim to solve global problems, many of which are in less developed countries and we should prevent x- and s-risks. Most of these goals are mostly independent of GDP in rich countries. However, on the margins, I think more GDP in rich countries probably makes it easier to achieve EA goals, e.g. more GDP means a bigger budget for pandemic prevention. Furthermore, I think it would be bad for EAs to support degrowth both because it seems less relevant than other problems and because I just don't think the arguments are true (as described above).

I will publish a slightly more details version of the above arguments and link it here so that you can engage with them more properly. Thank you, once again, for presenting the arguments for degrowth in this clear and non-judgemental way such that people can engage with them on the object level.

A couple of small points:

This may be a nitpick but actually the most popular renewables (e.g. wind and solar) need so much land that they could very feasibly be/already are a threat to biodiversity and land use. See image below for an illustration, from this work from TerraPraxis.

This seems like a big claim - what are you basing this on? I mean the Industrial Revolution led to the UK/Global North growing very fast without help from more developed nations so I'm not sure why less developed nations couldn't also develop quickly without growth in the west.

Also I think one of the stronger arguments of the post above is about resource use/other environmental constraints besides carbon emissions. It also seems like you agree that this might pose a problem for long-term/sustained economic growth? IMO this could be a consideration large enough to sway the argument in either direction.

I agree that wind and solar could lead to more land use if we base our calculations on the efficiency of current or previous solar capabilities. But under the current trend, land use will decrease exponentially as capabilities increase exponentially, so I don't expect it to be a real problem.

I don't have a full economic model for my claim that the world economy is interconnected but stuff like the supply-chain crisis, or Evergreen provided some evidence in this direction. I think this was not true at the time of the industrial revolution but is now.

I think it really depends on which kind of environmental constraint we talk about and also how strong the link of that is to GDP in rich nations. If there is a convincing case, I'd obviously change my mind, but for now, I feel like we can address all problems without having to decrease GDP.

"But under the current trend, land use will decrease exponentially as capabilities increase exponentially"

Most of the cost reductions in wind and solar to date are reductions in producing roughly similar technology more cheaply (somewhat less true in the case of wind and larger turbines), so I am not sure where your view for definite lower land requirements comes from (I think there is some argument for this being possible via next-gen renewables, but not from the perspective of past cost-reduction progress).

OK, thanks for the clarification. Didn't know that.

Regarding your "resource scarcity" section -- I thought that Harrington 2020 was pretty ridiculous for a variety of reasons. It simply re-runs the original "Limits to Growth" simulations, without engaging with any of the criticism those models have received, or even noting that the real world's performance has been far better than those models predicted. Furthermore, the Harrington paper blatantly moves the goal-posts, swapping out the environmental problems of the 70s (things like acid rain and industrial pollution and so forth) for climate-related CO2 metrics. Quoting from my comment about Harrington 2020 on another EA Forum post:

Thanks, didn't know that.

There are a couple of bait-and-switch moves in this post that I don't understand:

1. Paris-targets urgency vs big-picture eco-philosophy

"We're not on track to meet our Paris climate agreements; if we want to meet these targets we'll need a big transition right away" creates a reasonable sense of urgency attached to the issue of climate change. But then this urgency inexplicably carries over to big-picture philosophical ideas like "we are on a finite Planet Earth... at some point [maybe centuries or millennia from now], we will run out of crucial resources and we'll have to transition to zero resource-use growth", when it seems like we might have plenty of time to solve problems like the eventual scarcity of certain metals (including by doing far-future stuff like space settlement & asteroid mining).

2. Exactly how much degrowth are we talking here?

You don't clarify exactly what "post-growth" or "degrowth" means. Sometimes it sounds like you are advocating a massive worldwide economic depression of similar impact to the Covid-19 lockdowns, but lasting much longer. (Yes, you say that it wouldn't be as bad because only certain industries would be shut down, but the recession would also have to be more severe than 2020 in many ways, since the 2020 lockdown-recession didn't actually reduce emissions by much. So, figure the impact might feel about the same overall.)

But other times, you say that actually the ultimate goal is "avoiding an ecological collapse and its associated economic collapse", giving the impression that you favor approximately whatever mix policies lead to the best long-run outcome for human civilization -- striking the right balance between economic harms from global warming and economic harms from global warming prevention. Estimates from the UN IPPC say that even 3-4 degrees of warming (aka, blowing past the Paris Agreement targets) would only penalize the economy by a few percent by 2100. So (unless you think that all these climate studies are wildly wrong), it seems like it is only worth paying a small cost to prevent global warming: stuff like subsidizing green power (as in the bill just passed by the United States -- we closed half the gap between the satus quo and our Paris goals for only $300 billion!), approving more nuclear plants, implementing a carbon tax, and so forth. The couple-percent-of-GDP damages that mainstream climate science expects, don't seem like they are worth embarking on a many-percent-of-GDP, society-wide sacrifice of human wellbeing and development. So maybe "degrowth" is just a sexy, radical-sounding word for these sensible global-warming mitigation policies like carbon taxation and the like? In that case, I don't understand your choice of vocabulary but I am otherwise totally with you.

1. I didn't actually mean that the urgency in the climate problem leads to urgency in the materials problem, both are urgent relatively independently. It seems you're more optimistic about material scarcity and that by the time we run into troubles, we'll already have tech to solve them. Would be great if that were the case. I'd love to see forecasts on that if you know some.

2. The point I tried to make is that global warming is not the only problem. If it were, I wouldn't name it post-growth/degrowth, but I use these terms because of the bigger picture, since I also consider crossing the rest of planetary boundaries as well as resource scarcity important problems. But from #1, I think we disagree at least regarding the potential problem of resource scarcity.

The post is really nicely structured and written.

However, to me the key debate is not whether it's possible to have growth while (1) protecting the planet and (2) eradicating poverty. The question is how probable it is. I have generally found the arguments by the degrowth people quite convincing that it is in many ways improbable.

However, strictly speaking, the question is not even how improbable it is but the comparative question whether it is more improbable than having degrowth while (1) protecting the planet and (2) eradicating poverty. And this, I find even more improbable.

In other words: we should not just examine how growth makes poverty-eradication-cum-protecting-the-planet hard, but we should equally carefully examine how degrowth makes it hard -- and probably even harder.

"""Poor nations would suffer unintended consequences because they rely heavily on exports to rich countries → In fact, poor nations will benefit from it because as we internalize costs, they’ll get a fair salary and get compensated for environmental costs."""

This is, to put it mildly, implausible, and requires strong evidence IMO.

That you dismissed the most important issue with your claim so tersely without really engaging with it suggests you simply do not care very much about the effects on the global poor, which in a scenario without economic growth would I expect be much, much worse than the worst plausible effects of 3-4° warming (which I take to be the likely "business as usual" outcome). Citing Hickel here, a known bad faith/disingenuous actor in this area (see here) doesn't serve to provide much evidence either.

You may be right. I admit I lack the knowledge to answer that and I also see some potential problems for the global poor (in the post itself I already mention unemployment), about which ofc I care but I wonder whether they would be easily solvable or if they could be so big that it makes degrowth in rich countries unethical.

I have been looking for a while now for good literature that provides arguments or evidence how reducing growth in rich countries would hurt/benefit the poor.

I agree that Hickel doesn't seem very trustworthy on this. I have looked a bit at the degrowth/post-growth literature and haven't found detailed, convincing engagement on this question.

I've also looked elsewhere but I still don't know what literature to rely on -- despite its being such a core and straightforward question. Any advice on what to read on this would be appreciated.

Thanks for the post ! I liked it.

I also think that EAs are way too optimistic when it comes to reach green growth. Most large scale environmental problems have gone worse globally, and continue to do so today, despite way better technology.

In my view, thinking that we'll somehow solve something we failed to adress for the last 50 years, despite ample alerts, and despite decoupling being the main environmental policy... well, this strikes me as rather risky.

If you're interested, I made a post on energy depletion that also adresses the issue of limits to growth. The second post adresses decoupling of energy and GDP. However, I'm more skeptical of the possibility that we'll do a voluntary degrowth: the third post adresses that.

How realistic are the optimistic views that technology will be able to deliver, fast enough, green energy, mitigate climate change, and bring us back under all the remaining planetary boundaries?

Predictions by International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook versus reality:

How likely is it that we won’t run out of any crucial resource in the next century?

On a planet of finite resources, it doesn’t seem like we can continue growing indefinitely – Under business-as-usual, when would we reach plateau/collapse?

Think of how foolish it would have been to throttle energy/resource use 100 years ago to protect ourselves from running out at 100-years-ago levels of use. When we start to run out, we have many options: alternative resources, efficient use, dilution, recycling, etc. This will extend the clock many fold. Resources may be finite, but need for them is not constant. I am confident they will become outdated in time, as resources historically have thusfar.

There are lots of very concerning problems arising from overapplying GDP, capitalism, gerontocracy, and neglecting environmental issues. But the above particular points do not seem substantive to me.

Regarding your "Do we need growth in rich countries?" section -- this strikes me as a failure of imagination. You are willing to look back across history and say that life has gotten vastly better in many ways with advancing science and industry- -- modern medicine, the conveniences of travel and telecommunications, etc. But you don't seem willing to make the obvious extrapolation into the future -- in a more prosperous and more energy-abundant world, don't you expect that society could become even better? People could afford better medical care, society could more easily afford to redistribute and create equality, society might even become more participatory and democratic?

People in 1960 would have made your same argument -- "The USA and Europe don't need growth; we're already so prosperous, we've basically achieved everything you could possibly want." But looking back, we can tell that they were wrong -- life has improved in important ways since 1960, and even since 1990! What makes your argument any more likely to stand the test of time?

In other words -- sure, the USA doesn't do quite as well on quality-of-life metrics as some countries in northern Europe which have a slightly lower GDP. It would be great to learn from those countries. But also, neither the USA or Europe represent the highest potential of human civilization -- so much more is possible! For a vision of what this better future might look like, here is an optimistic, utopian story I put together with some friends of mine that tries to illustrate what a fairer, more democratic, and more abundant world could be constructed. Here are some relevant quotes from that project:

I agree that more GDP in rich countries may lead to improvements in many areas. However, I think that 1) we can't afford it given the problems of climate change, the rest of planetary boundaries, and resource scarcity; and 2) we may be able to improve in many areas without further growth, by investing on those areas which matter and shrinking destructive industries. Due to 1), we may need to compromise. If 1) isn't true, then great, let's continue the improvements!

Thanks for the link to your utopia project, looks really interesting!

A discussion about GDP growth and climate change (1) doesn't really add anything to the known economic strategies to end emissions (sinking lid carbon caps) (2) nor does it engage with the key pressures preventing us from implementing them. So I agree with you that we shouldn't be too concerned about impact on GDP through carbon mitigation, but also think arguments in favour or against that aren't really engaging with the critical solutions or challenges.

On the solutions side: economically, at the level of economics design, a sinking lid carbon cap makes it very simple. We set a carbon budget from now to 2050 based on the level of temperature increase and other climate impact we deem tolerable. Then, anyone emitting carbon has to buy emissions credit out of the limited budget available. I'm not saying governments should entirely leave market forces to sort it all out--there's a strong argument to helping them along with e.g. tailpipe emissions regulations. But economically that'd be sufficient. Under this approach you don't have to worry about whether you get growth or degrowth or something in between--just set your target and the economy will adjust to achieve it.

I suppose I must concede that some people trying to decide exactly what level of emissions, or temperature increase, we might want to tolerate treat it as a GDP optimisation problem. What level of temperature increase maximized GDP given the cost of avoiding to climate change against the costs of experiencing climate change?

But there's also the key political pressures that keep us from implementing carbon budgets. Oil prices went up this year by a lot, and this has led to high inflation across the economy, according to some experts, and has been experienced directly by consumers as higher costs to fuel combustion engine vehicles. Political leaders of all stripes including Biden, who ran on a platform of lowering emissions, amongst other priorities, have responded by trying to get oil prices down. That's the exact opposite of what you do to avoid climate change, but it might be the only choice democratically elected leaders have to respond to public concerns in order to be elected again. And voters aren't primarily concerned about maintaining topline growth; they want to know: will I have a job; will I keep my job; can I afford to drive my car? GDP is a contributor to all those things, and SWB measures definitely decline during recessions. but a debate on GDP targets and subjective well-being won't help you understand how to get support from voters for a tractable climate change response.

So I am left wondering the value of framing the question in terms of GDP at all, except perhaps in setting an economically optimal temperature increase limit target for carbon credit schemes. Maybe that kind of puts me in agreement with OP? But I disagree that the inevitable conclusion is that we need to "shrink material throughput". What needs to be shrunk are greenhouse gas emissions, and to target growth in a positive or negative sense from the outset seems misplaced.

I'm not sure I'm following your criticism against framing the question in terms of GDP, since my point is that we shouldn't really care about whether it grows or shrinks, and it seems that you agree (when you mentioned the carbon cap).

Alright, so we agree we need to reduce GHG emissions, but when I say that we need to "shrink material throughput" it's not a conclusion, it's a separate point. To reduce GHG emissions it might even be better to grow our economy, but I think shrinking resource use and caring for the planetary boundaries are also important, and I'm more skeptical that this can be done under further economic growth.

I don't have strong opinions on the object-level of whether marginal increases in growth in rich countries is net good (I think I have substantially more sympathy than most EAs that it's net bad). But I think the argument is unlikely to primarily route through climate change, for fairly simple reasons.

1. Transformative AI and engineered pandemics are substantially more important than climate change.

2. GDP growth probably has a substantial impact on AI and pandemics.

3. Climate change and environmental degradation also has some impact on AI and pandemics.

4. However, I think it will be quite surprising if the third-order impact of GDP growth -> climate change and environmental degradation -> AI and pandemics is higher than the second-order impact of GDP growth -> AI and pandemics.

5. Thus, to investigate whether growth in rich countries on the margin is net good or bad, almost all of the "action" will come from investigating the effects of growth on AI, and maybe bio/pandemics as well. It is unlikely to come from two layers of indirection.

I'm curious where the crux is. My current guess is that the main crux between me and the OP is (1). I agree that this is a nontrivial question (one of the most important cause prioritization questions) and I do not plan to answer it here.

Interesting post, here's a few thoughts:

"It is too late for organized degrowth because climate change is now driven by intrinsic feedbacks as well as anthropogenic GHG's. Change in both GDP and GHG production will depend primarily on global response to ongoing climate and ecological disasters. Population control will drive itself, through massive suffering and death caused by climate disasters and a change in public sentiment toward conceiving children, or just living, under much worse conditions than now."

You seem to want degrowth, and I agree with you, it's the only honest option, frankly, but you're looking at the climate change aspect through a model of GAST temperature rises driven solely by anthropogenic GHGs. I just want to know why.

You're looking for some hope and cheer. Seen from this perspective, nanotech offers it. There might be other problems associated with its use, but realizing its full vision would give humanity tools to solve most environmental problems rapidly.

There are many possibilities, I favor nutrition that does not require:

* refrigeration

* high-moisture content

* cooking

In particular, powdered drinks or crisps, vacuum-sealed single-use dissolving oil packs, and liquid extracts of vegies and fruit (when those are available). You add water to the powdered drinks.

You're probably familiar with fermentation technology used to make milk proteins, do you have an opinion about the technology? I heard a few mentions about it recently, including a potential commercial milk product based on the technology.

Let me note that governments are making plans for an ice-free arctic rather than looking to prevent the ice loss. There's talk of fishing, drilling, shipping lanes, and military movements in arctic waters once the ice is gone.

A megaflood from an atmospheric river covering California for several weeks would create an inland sea, flood cities built on flood plains( like LA), and cut off critical transit routes. Death by dehydration or starvation could occur.

California might lose most of its population to migration or other causes during a megaflood. California megafloods might occur too frequently to make large-scale resettlement of the state feasible or attractive.

In such a scenario, what are the knock-on effects of that flood? California is a big economy on its own, and a major food grower. It would create a pollution disaster across the state, destroy most California infrastructure, wipe out Silicon Valley businesses, disrupt internet and power delivery in other areas, lead to production losses in some industries, kill some people, and force most people to leave (if they can) as the rains continue, provided the state or the feds can help in the event of a megaflood, not a sure thing.

Interestingly, California is also vulnerable to mega-tsunami's, but those occur less frequently than megafloods, and afaik, their frequency is not affected by climate change.

You did a lot of work to explore the area of green growth vs degrowth, have you thought about turning your attention to scenarios like large-scale weather disasters and specifics to prepare for them? I would be interested.

There's a pathway through which humanity does its best to help ecosystems restore themselves. The scenario is plausible but the devil is in the details. Do you believe that the completion of the 6th great extinction is inevitable? Can it be reversed?

Assuming something happened like a large drop in ocean biomass within a relatively short period, say a decade, what could be done to limit its impact on terrestrial ecosystems? Could we bring back the plankton without removing atmospheric CO2?

I asked a lot here, I don't expect you to address it all, of course, just whatever you'd like.

Thanks for your excellent post, by the way!

Thank you for your points and questions.

1. I focus only on anthropogenic GHG simply because despite feedback loops being also very important, it'd be too much off-topic.

2. That'd be great!

3-6. Unfortunately, I don't know enough about the topics to say anything valuable, but interesting points.

To add to my comments yesterday, while GDP growth doesn't seem to drive subjective well-being (SWB) in Western countries, recessions certainly harm it. You acknowledged unemployment could be an issue. I don't know if shifting to a four day workweek is a good idea to generate extra jobs because (1) it's authoritarian to stop people from working five days a week if they want to (2) people will suffer a real loss of 20% of their income and they may suffer in SWB terms as a result (3) many jobs are not super fungible and 4 workers doing 5 days a week can't simply be replaced by 5 workers doing four days a week without a lot of retraining (4) slowing down parts of the economy unconnected to carbon emissions will lower output unnecessarily (as an example, if you cut teacher hours by 20%, it isn't clear how this meaningfully reduces carbon emissions because teaching isn't a high carbon occupation, but you will suddenly have to higher an extra 25% more teachers if you want to keep total teaching hours the same) and (5) while GDP growth doesn't raise SWB, GDP declines could still lower it. Humans are loss averse, and tend to want to avoid losses more than they want to approach equivalent gains, by a ratio of about 2:1.

It does seem like good public policy partially protects against the SWB impacts of unemployment and recessions (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42413-019-00022-0). However, (1) that doesn't mean it's entirely protected and (2) we can't snap our fingers to get better public policy --that'll take work.

Yeah, recessions tend harm SWB, but I don't see why a planned degrowth as I picture it would: e.g., if people work less, they'd earn less, but if we have UBI and more welfare, we may end up having more in the end.

Reg #3&4: decreasing working hours would be costly (e.g., retraining). But if we're to consume less, we'd produce less, so there'd be less jobs available, so we can redistribute working hours. In reference to #1, it should ofc not be made in an authoritarian way, but I think there should be other ways, and less working hours should be related to more job satisfaction/more SWB.