TL;DR: In summary, it is unlikely that our societies will start using less energy willingly at a global level - especially as the topic is neglected for a host of reasons. However, there are many things EAs could do, including finding ways to produce food and basic goods in a less energy-intensive way, or helping build more resilient territories that would be less threatened by sudden disruptions. You can check the short version of the post.

Note : This is part 3 of 3 posts on energy depletion as an important topic for EA. I recommend reading part 1 and part 2 before this one, or the short version. This part will address the actions we can do - but an important step is also assessing what has very little chance of working out as a solution.

Part 1 and Part 2 explained how it is likely that we will have less energy in the future, and that this implies serious consequences with a lot of unrest. This post tries to answer the question we all have in mind: what can we do? But first, we need to talk about solutions that could take place in an ideal world, but are unfortunately intractable with our current power. What can’t we do?

Is it possible to convince governments and companies to seriously anticipate that?

The first thing that comes to mind about this topic is that governments and companies should do something. This is very true. A reasonable way to tackle this issue would be to put in place a rationing over the resources left, in order to use as little as possible. This would allow us to prioritize essential uses over the others in order to ensure a safe transition toward a sustainable civilisation (putting a cap on stuff like commercial planes, single-use plastic, shopping malls or SUVs in order to preserve hospitals, tractors and public transportation). A way of doing that could be a very high tax on fossil fuels for non-essential uses. Then, invest massively in all alternatives to fossil fuels in order to solve at best the hurdles mentioned above. If a significant part of humanity’s resources and inventivity were used here, a smooth transition could take place.

The issue is that we are not doing that. The political responses so far focus on technical improvements (and energy efficiency, addressed later), but they rarely address the need to use less energy. To the best of my knowledge, the most mature political action today that addresses something close to this issue is the Green New Deal, which is still being actively discussed essentially in the EU and USA. Those plans, however, focus more on global warming and the development of renewables, but they tend to underestimate the difficulty of switching away from fossil fuels, as seen in the GTK report. Here are the elements that suggest a strong political action on the subject is implausible:

- Focus on economic growth: One of the goals of most governments is economic growth. But as seen before, using a lot less energy means giving up on economic growth, something that very few markets or politicians seem to consider acceptable, even if temporarily. This is understandable since the debt system and modern institutions like the retirement system rely on growth to work correctly, and would seriously reduce tax revenue. The persistent lack of political success of degrowth advocates (or post-growth, or steady state), starting with The Limits to Growth in 1972, seems to indicate this is not an option governments and markets will follow.

- Current transition scenarios underestimate the difficulty of the task: A few policies try to promote less energy-intensive behaviors (biking, building insulation, using public transport), but, as we’ve seen, most of the scenarios published about the energy transition do not take into account the diminishing returns of fossil fuels and minerals extraction, plus the impact on growth and investment. For instance, the model used by the International Energy Agency (IEA), the go-to for decision makers, doesn't seem to model these points.

- Current structures focus on the short term: Companies have trouble seeing ahead of 3 to 5 years in the current market. The mandate of politicians in western countries is of similar length. The energy problem spans over decades, so the concept of “saving energy now to use it later” is a hard sell.

- Global competition puts serious constraints over companies and politicians: Companies, if they decide to sell less products in order to spare some energy, will be less competitive than those that sell more aggressively. In the absence of laws that put limits on energy consumption, companies cannot act on their own. Unfortunately, such laws tend to be unpopular (they mean reducing the population’s standard of living), and therefore have little chance of happening in democracies. Politicians, constrained by the need to be reelected, tend to shy away from such proposals. Of course, when many politicians affirm that it is possible to do an energy transition without changing our lifestyles, those who say that we need to do some sacrifices are at a great disadvantage.

- For instance, US president Jimmy Carter addressed his nation on the subject in 1977, between the two oil crises, saying “With the exception of preventing war, this is the greatest challenge our country will face during our lifetimes”. But his energy policies were contested from both sides, everybody disagreeing about what to do, and he wasn’t even reelected.

- Similarly, high taxes on fossil fuels, while useful (they managed to decrease gasoline consumption in Iran), are unpopular if they get high enough. Several governments that tried to end their oil subsidies had to face widespread protests, riots and strikes, and had to capitulate, like in Bolivia or Nigeria. The main trigger for the massive “yellow vests protests” in France was an increase on fuel taxes (seen as unfair as it also targeted the poorest). Such examples tend to discourage other leaders from taking action. These taxes could also lead companies and industries to move to countries with less regulation.

- International treaties make action difficult: International agreements have been signed to establish a multilateral framework in the energy and mining industry, such as the Energy Charter Treaty. Those treaties cover trade, investment and transit of energy, and promote the openness of global energy markets, and are highly constraining. They allow private companies to sue governments for damages if the value or future profits of private investments are hurt by new legislation. In the Yukos Oil Company’s case, Russia was forced to pay a $50 billion fine to the shareholders. Moreover, countries are also competing among themselves — if one decides to limit its energy consumption on its own, other countries will use this energy anyway, and be economically more competitive.

For all of these reasons, current (and probably future) policies on the subject are not up to the task. There is investment in renewables, but often in order to get more energy, in addition to the current stock. There are efficiency improvements, and they can help, but they are often partly compensated by a reallocation of saved resources and money to either more of the same consumption (e.g. using a fuel-efficient car more often), or other impactful consumptions (e.g. buying plane tickets for remote holidays with the money saved from fuel economies). Whenever energy is saved, it is used somewhere else in the system. While efficiency improvements are definitely useful and have greatly increased in the past century, this has not ended up in less energy being used globally, because of this rebound effect. In some cases, efficiency improvements can also lead to more vulnerability toward supply chain disruption, for instance by using more complex high-tech processes that are harder to maintain and repair (e.g. by putting electronic devices everywhere, from cars to buildings). For instance, alloys used to reduce a car’s weight often need scarcer materials. Moreover, energy efficiency cannot grow indefinitely either.

To conclude, even if there might be interesting alternatives that should be developed, like how to make transportation, medicine or fertilizers while using as little fossil fuels as possible, there is a real risk that they won’t be implemented in advance if that means challenging economic growth — at least with the current decision making process. Most policy recommendations that plan for a long term sustainable system are likely to be ignored — like the ones formulated by degrowth advocates. Here is an example suggesting that convincing governments to take strong action is unlikely to work: when the US government asked for a report on what to do about peak oil in 2005, all additional research on the topic was stopped after seeing the implications. Here is some (limited) data for other countries. Clear and important negative consequences are currently necessary before any important change is done.

Why is this issue neglected?

So, except maybe for nuclear and fusion power, one area is currently not neglected: finding ever more energy sources. There may not be enough investment in alternative sources, but many actors are already pushing for it (including, surprisingly, oil companies). For this reason, we shall not spend a lot of effort there. Pushing for changes in the overall economic structure has not been neglected either (whether it is with degrowth, post-growth, doughnut economics, steady state, anarchism...), with very few results.

Is it possible instead to inform citizens everywhere in the world and to get a mass movement that would pressure politicians? This is going to be complicated. As the subject of energy is regularly mentioned in media and policies (especially on renewables), there is an impression that this issue is currently being worked on, or that there is no immediate threat - even if many analyses and solutions proposed on this matter are inadequate. Why is this still a misunderstood and neglected problem? A key element is that it is really hard to find good information, for the following reasons:

- Most governments, international organizations and companies are not reliable sources of information: As opposed to climate change, where relevant information is in the air, the current state of oil reserves is not publicly available. Proven reserves are stated by the oil companies, the producer states and the consumer states, and all three have reasons to overstate these reserves. Companies might want to increase their potential worth, and cannot say that they can’t provide enough supply (although there are a few articles there and there).

- Governments, on their part, might want to preserve public trust, lest they trigger a financial crisis, as seen above (for instance, the USA put some pressure on the IEA to make sure their results aren’t too pessimistic). As Colin Campbell, a former executive of Total, said in a conference: "If the real [oil reserve] figures were to come out there would be panic on the stock markets… in the end that would suit no one."

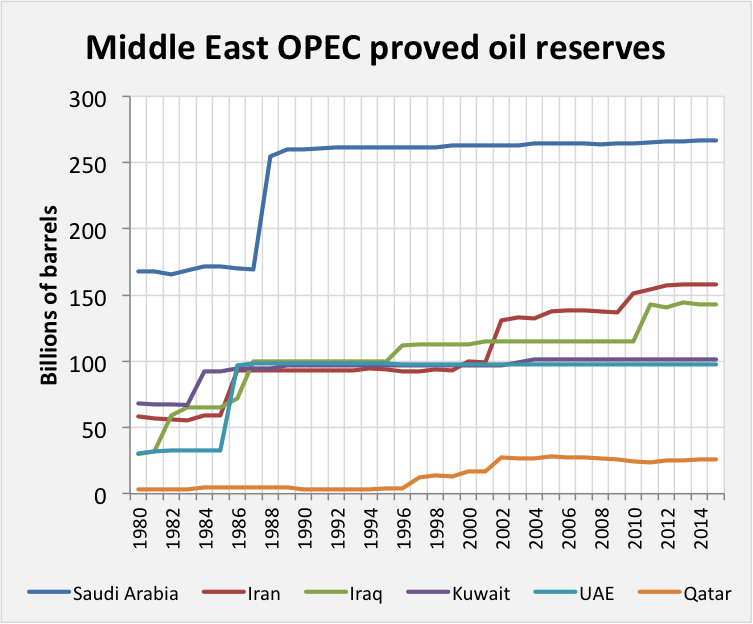

- Producer countries often are not reliable either. OPEC countries have exportation quotas that are proportional to the amount of proven reserves, so they often keep that number stable in order to keep producing the same amount. If you look at the “proven reserves'' of Saudi Arabia, they have barely changed since 1990 — despite decades of consumption and no major discoveries (a “mathematical impossibility”). Iraq was even less subtle: in 1987, its reserves went up to… 100,0 billions barrels.

- This is an issue because these figures are used in the often quoted figure “50 years of oil left”. In fact, the oil industry itself does not rely on these estimates. They rather turn to private analysis companies, the most reliable of all being Rystad energy, but whose results are behind a very expensive paywall… Only one NGO ever got access to it, the Shift Project: its data was used to publish the French report on peak oil quoted here.

- Thinking in silos makes us miss the big picture. A good example of this are the Green New Deal and IEA projections and policies. One common reaction, when being exposed to the problem, is to immediately jump to a unique solution, like “we should develop electric cars, or nuclear energy“. The issue is that by doing that, we miss out on all the other limits: the car or reactor needs fossil fuels to be produced, we switch our dependency on metals, trucks that carry parts are hard to electrify, and the economic system runs into trouble with less energy. Our current way of analyzing only parts of the problem is not adapted to the task at hand: a transversal view is necessary. However, as individuals we are very specialized, and relatively ignorant of what’s happening outside our field of reference. This is why science in its current form is currently ill-equipped to analyze the issue: most economists tend to ignore the energetic basis of the economy, while most scientists that make energy transition scenarios tend to underestimate the reasons that make the economy so unwilling to change. Taken individually, each section of the problem might appear solvable, but all of them at the same time? Systemic thinking, that focuses more on the interrelations between all the different parts of society, appears necessary.

- The hypotheses used by most economists are also poorly suited to the task, and do not even consider the possibility that an energy descent takes place. Their models do not use energy and materials as an input, assume perfect substitutability, and that current prices are good indicators of long-term resource scarcity. An example: as energy is around 5% of GDP, economists often assume that suddenly cutting energy production by half would decrease GDP by only 2-3%, despite the fact that this would cut down transportation and manufacturing by half, or close to it. See this podcast or this article to understand why these models are very poor tools for this problem, despite their immense influence on deciders.

- Many biases make us ignore the possibility of a catastrophe. Eliezer Yudkowsky made a list of these biases: availability (we have no recent experience of such a situation, but we have examples of people announcing the peak too early); black swans (we have trouble anticipating big uncertain events); affect (we are attached to our current lifestyles); motivated reasoning (the narrative of “we’ll find a solution somehow” is something we want to believe in)... The list goes on.

- An aggravating element is that we have an entire history of material and energetic growth behind us. We were born in the middle of this growth and came to consider it as the normal state of things, so it is very hard for us to imagine a disruption, and what a world with less energy would imply. Most people make decisions based on their sensory inputs, not abstract data, so they look at their everyday life and do not see a problem (which is understandable). Those biases make solutions hardly acceptable for most people and thus are unthinkable for current decision-makers.

- We fail to see the importance of energy as few people talk about it: As it is rather invisible in our daily lives, energy is taken as a given. The role it plays in the economy, history, politics and in the making of industrial civilization is often overlooked, and barely mentioned in school or the media. Since few people talk about it, it is often ignored. For instance, the crucial role that energy played in the 2008 financial crisis is seldom mentioned. It’s likely that the role of energy depletion in the next crisis won’t be explicitly mentioned either, and most people will be confused about what is really happening, especially as the impacts might vary from place to place.

- There is no plan toward global sustainability that is both mature, realistic, attractive and applicable at both the global and local scale. People tend to move away from problems if they see that there is no readily applicable solution (not to mention politicians). Humans are adept at blocking or dismissing information perceived as threatening, and this one is rather overwhelming, so a natural reaction is to search for anything that looks like a solution in order to avoid digging more into the topic. “We’ll just use that, problem solved”.

- Nate Hagens actually tried to discuss about this issue with many people, even Wall Street traders, and when faced with the overall logic, they ultimately did not disagree. The only thing they wouldn’t agree on, though, was the timing: they thought that the limits were not going to happen within their lifetime, and that it was their children’s problem. He also said that young people and ederly were more likely to take this issue into account (concerned for their lives or that of their grandchildren) - but people between 25 and 65 years old, much less.

Nevertheless, some work has been done by think tanks and researchers to propose ways toward a sustainable world, but they are not sufficiently known to decision-makers (when they are not completely invisible), or sufficiently mature. From the economic perspective, there has been work on green growth, degrowth, prosperity without growth, steady state economy, doughnut economy, wellbeing economy... For work more focused on energy, see The Shift Project. Among the research community there are some low impact journals like Energy, Sustainability and Society, Sustainability Degrees, and Sustainable Cities and Society. This article also summarizes many findings.

Still, all of this is almost absent from the public debate, and this is likely to continue for quite some time. Since the energy descent will have a major influence on humanity’s future, any discussion on pretty much anything should take that into account — and especially in EA, with its focus on the long term.

What we can do about this

More research is needed

For such a global, technically complex and multi-generational issue like energy resource management, for which our intuition is of little use, many actions and adaptations of diverse nature and scale are required. Some examples include:

- Increasing our knowledge and sharing it, especially in the field of social and economical sustainability.

- Improve decision making at every level of society

- Ensure efficient implementation of actions and adaptations

- Promote better, more realistic forecasting of energy and other resources

The EA community, with its limited means, cannot tackle every one of them, so I will focus here on actions EAs could be interested in. They are described in logical order rather than importance or relevance. You are free to evaluate their pertinence.

First, there is a need to dispel some of the uncertainty that surrounds this topic. Because of its technical complexity and the need of making projections, this problem requires yet more scientific investigations. In particular, research about what a sustainable society and economy could look like, and how we can transition toward it is still necessary. Some innovations in the way we make research in this field might be necessary, to take into account interdisciplinarity.

It may be very difficult or impossible to find a system both sustainable and one that leaders would want to transition to. If a large-scale transformation is too big of a task (especially for behemoths such as markets and states), it would be more tractable to work on a smaller scale, and target territories first.

The second consideration is to develop plans, strategies on how to provide the needs of everyone in a situation of sudden shocks, most importantly on how to feed people with little energy, and provide them with the necessary goods (like medicine). Such plans should include means on how to share this knowledge to everyone in such a situation to prevent panic. Education on the subject could also be important, because without a fair understanding of the problem, it will be hard to act accordingly. Another element of importance would be to find ways of lowering the impact of a big financial crisis. Preparing for a rationing system. Making stocks. Improving local production of essential needs. All of this is hard of course - a good analogy would be “how do you stop a Ponzi scheme from crashing down too hard?”.

List of actions we can take

Here are several things that can be done on the subject. This list is rather tentative, and I don't really know to what extent they can be cost-effective, or even doable. Everything on the subject is difficult to predict and rather complicated, so it will need quite some research in order to find the most effective actions. Here are some leads:

- An interesting first step would be to get in contact with the networks that have been working on this subject. Resilience.org and the Post Carbon Institute are references in this domain. They published several papers that might be of use, like The Future is Rural, that helps understanding how to handle the energy descent for agriculture. The Transition Network has spent quite some time on the subject, they could help as well. I didn't check them fully yet, but The Simpler Way and Transition Engineering also seem to have good leads. Current practices are hard to change, so advice on how to help make the switch would be precious.

- The only EA organization (that I know of) that works on how to feed everyone if industry is disabled is ALLFED (Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters). They research scenarios based on sudden shocks like “10% loss of industry” or “10% global agricultural shortfall” (or even worse, crises that disable everything). Their work could be very relevant to the matter at hand, especially the low-tech solutions. They suggest very promising things to do in order to provide basic needs. For instance, emergency food could come out of leaf protein concentrates, seaweeds, or animal feed that could be reallocated to humans — it’s (theoretically) possible that these could feed everyone. David Denkenberger also studied how to do on-site nitrogen-fertilization of corn using solar photovoltaic electricity (instead of fossil fuels).

- They made some research on other needs — for instance, current ships, relying on heavy fuel, could be rehauled to work with kites, and still sail at a slower pace. An important point they mention is the dissemination of this information to the people who need it — for instance, a network of shortwave radio receivers could be used to share all of the emergency actions to take. This could save quite a lot of lives, especially if it allows people to be fed during the downtime that will be needed to rehaul the food system. While some doubts have been raised regarding their estimates, the case for more research in this area is strong, and could be a particularly effective action to take.

- Developing food autonomy seems a priority: you can’t allow your food system to depend entirely on trucks that depend on oil. Since agriculture would be less and less mechanized, more and more people will have to work in a rural world again. Policies that help develop local food autonomy are crucial, as are agricultural students, teaching and researching sustainable farming methods. Cuba’s success in surviving its loss of oil imports after the USSR’s collapse was partly due to having enough people trained in organic farming to train petrochemical farmers how to switch to organic methods. I didn't read it yet, but there are ways of farming like Carbon Farming Solution that requires less fertilization while increasing yields.

- Helping the transition diets towards more plant-based is important, since factory farming is currently a huge consumer of cereals, crops, and water — so not sustainable at that scale. Moreover, less crops for animals would mean more biomass available, one of the only options for trucks and high-heat.

- Developing policies that allow for more resilience, and to adapt in case of sudden shocks: being able to keep a healthy social fabric and foster solidarity, to adapt quickly to changes, to understand the situation and work accordingly, etc. Reducing dependency on external inputs will be important, especially in regards to water (like clean water sources and a lot of storage for chlorine), medicine (with medicinal plants) and energy (with maybe some solar panels and windmills to help for the transition). Policy makers might not be convinced by a “peak oil” approach, so other arguments could be used — more autonomy, supporting local jobs, “if another pandemic blocks imports from China again, what would happen?”, etc.

- As the german army report puts it: “While it is possible to identify specific risks, this does not conceal the fact that the majority of the challenges we are facing are still unknown. Besides adapting economic and energy supply policy at an early stage and not only in highly industrialized countries, the probably most effective solution strategies are thus not concerned with specific countermeasures but with systemic “cardinal virtues” such as independence, flexibility and redundancy”

- With less transport and trade, local territories will have to make use of their local resources, at least to meet its basic needs in case of trade disruptions. We could help develop the new political, social and economic systems best adapted to this situation. Democracy could work better at a scale where everybody knows their elected officials. Reflection toward that end can stem from concepts like libertarian municipalism of Murray Bookchin, Councilism and Democratic confederalism, and their implementation successes and failures. Of course, no single system will fit all needs and cultures, so it shall be adapted to the local context. Change from outside might not be accepted so the support of local leaders is very important.

- It’s also possible that these societies and leaders might not want to adopt new practices widely right now, as they want to preserve the statu quo, but they could turn to these practices if they are available when hardship unfolds (for instance, a local money that proves less vulnerable during a financial crisis would be attractive and adopted more widely).

- Mental health. This is a distressing subject, and many people might break down when things turn out worse than expected, especially in cultures where death is taboo and not a thing we should even consider. Decline is not something we like, so that might deeply shake the beliefs of people who assume a future of continual growth — especially if they don’t have something else to give them a sense of purpose (a strong community, religion, spirituality...). Surviving physically is not all. Help on how to accept and handle the situation might be very useful, especially on how to find well-being in other ways than in consumption (for instance, a good way to get better is action: tackling this subject in an active way).

- Develop low-tech approaches and tools that may be usable and durable even without long supply chains. Sharing the knowledge gathered during the last two hundred years in order to smooth out the transition could be very useful — for instance, how to build an insulated house with as few materials as necessary. That also implies to store it on media more durable than hard drives. Other intel of importance is how to make tools (including farming tools), fertilizers, soap, medicine and first-aid kits, lights, stoves, toothpaste, ovens, devices that purify water… The low-tech lab has a list of projects, and you can also check the low-tech magazine. There are some sailboat, watermill or windmill designs that outperform traditional designs. These solutions are currently not widely known and might not be accessible to all when difficult things happen. So disseminating all of this crucial knowledge to everyone in need would be an important step.

There are certainly other things to do that could be more impactful, and I don’t know which ones yet. This is why I need your help and your expertise.

Should we push for more energy?

Note: From now on, this is just my personal opinion. Feel free to do what you want with it.

You might have noticed that an action was missing: getting more energy. Indeed, the common reaction when faced with this problem is to propose the development of alternative energy sources, and counting on technology and innovation to solve things. Do we push for renewables? For nuclear power? For fusion? What I suggest, instead, is that we spend only a limited amount of effort on pushing for more energy sources.

This is quite a surprising statement, so let me explain. First, as said before, this way of action is not neglected, and there is more and more a financial incentive to do that. Second, it’s likely that most solutions would only delay the problem by a few decades (because of limits on minerals, or because other limits to growth start kicking in like pollution). In such a case, we’d be back to square one after a few years, having increased pollution, resource depletion, biodiversity collapse and climate change in the meantime - and making the impact of a decline even more difficult to handle. Moreover, a delay would mean that the world would be able to continue with factory farming at the current scale for a longer time, and “accidentally causing factory farming to continue” is the very last thing an effective altruist would want.

Third, many of the solutions usually proposed do not take into account the vulnerability to systemic risks and supply chain disruption. High-tech products that depend on very long supply chains would be more vulnerable - they are also more complex, more difficult to recycle and repair. Research on fusion, specifically, would be hugely impacted (see here for more on the fusion question). Nuclear fission reactors work well in a stable environment, but they could also get dangerous in case of wars or big crises (like in Ukraine). Moreover, decommissioning old nuclear plants and treating radioactive waste is extremely costly (about $1 trillion over 2001 to 2050) and it’s uncertain that a lot of funds would go there in case of a big recession, leaving a dangerous gift for future generations.

There is a last point that may be more controversial - if we got infinite energy, I think that this would make our overall situation worse. Not better, worse. This is a strong statement again, so let me explain. I’m not certain that we, as a society, are really good at handling a lot of power (= energy). We now have so much power that under business as usual prospects, we have about a 1 in 6 chance of ending up in an extinction scenario (there are actually many estimates, some say 1%, some say 50%, so I took Toby Ord’s estimate. Check this database for more).

So the prospects of the current industrial civilization are very bad, especially when you include rogue AIs, total nuclear war, EMPs, massive environmental impact, or gene editing. I think that solving the energy problem would highly increase our probability of ending up in one of these extinction scenarios. I understand that the “expected value” of expanding into the galaxy would be so high that it would “offset” taking these risks, but as said above, I don’t think this is a realistic prospect. Richard Heinberg makes the case that we are overpowered: we have so much energy that we risk wiping out ourselves by accident. Worse yet, the goal of our current economic and political structures is to get even more power - forever.

A better goal is needed. If we were to get more energy sources, what would make sense would be to look for the ones that are more resilient, usable locally, repairable and overall more sustainable. But even before that, there’s an essential question that we’ll have to face in the coming years: What are our actual needs? Where are we headed?

We need a new vision of the world

Before delving deeply into this topic, I guess I viewed the world through a lens that many of us had:

- That growth was caused by human ingenuity, which is unlimited

- That our current industrial civilization represented the pinnacle of progress, the natural outcome of human history, and would continue for a long time

- That markets would adapt to compensate for energy depletion, and switch to alternatives as long as they are technically possible

Given all I found during the last few years, I had to update many of my core beliefs. My conclusion is bound to change, of course, but I now tend to think the following:

- That every civilization in history tends to follow the same pattern: growing, reaching a peak, and declining (quickly or slowly), because of diminishing returns. Why would our industrial civilization be an exception? I mean, even neoliberal French president Emmanuel Macron is saying that “We are living the end of what could have seemed an era of abundance… The end of the abundance of products, of technologies that seemed always available, [...] of land and materials”. It’s like aging, really: not something we necessarily want, but hey, it’s there.

- That energy flows are precious for understanding reality, and the tremendous growth of the last centuries wouldn’t have been possible without the exceptional energy density, abundance and flexibility of fossil fuels, which are only a temporary gift (or curse, it depends for who). The future will not be a prolongation of past trends.

- That this society, like most others, had good outcomes for some beings and bad outcomes for others. It was really good at keeping many of us alive and providing a lot of comfort. At the same time, it was extremely cruel to animals and not really good for mental health (studies point out that there is a “growing burden of chronic diseases [like depression], which arise from an evolutionary mismatch between past human environments and modern-day living” - I’m aware that studies point to lower happiness in “less developed” countries, but I’d argue this has a lot to do with colonization, its consequences and inequality). So the transition will be bad on some aspects and good on others. But this is a topic worth its own post.

- That many human societies voluntarily did not try to pursue material growth in order to avoid issues like environmental destruction or too much power accumulation. Instead, these societies preferred stability. Not sure I can blame them; I don't think I can say our industrial civilization really is superior when our odds of survival are about as high as in a game of Russian roulette.

- I also found that raising material wealth is not really good at increasing long-term well-being - our brains just adapt after a few months - so equating economic growth with happiness does not work very well beyond a certain threshold. Many other societies had to find happiness in a fulfilling social life, beauty, or spirituality. From personal experience, focusing on these goals, slowing down and consuming less actually increased my well-being. Who knows, when it will be clear that we’ll have less material goods in the future, maybe many people will also turn to these things? That doesn’t seem like a bad goal for society. But this is a complicated topic for another post.

Given the many challenging things we talked about here, you may feel at loss. Then I really advise you to watch this, about what to do about that in your personal life, how to cope with this information, and how to make the best of it.

Conclusion

I’ll conclude by using the words of Nate Hagens (I really recommend this video): “The [coming] simplification will be among the most significant events ever experienced by our species. Those who look through a systems lens can serve as early visionaries of a simpler life with new ways of relating to technology, to consumption, to each other, and to Earth's ecosystems. Some are wise, humane, and even preferable to what we have now. Some are so dark as to be nearly unthinkable. Yet it is precisely thinking about these pathways and actively choosing among them which offers the only realistic hope for a long and meaningful human future. The future need not be dystopian but cleverness alone will no longer suffice for the next leg of our journey. We will need imagination, foresight, empathy, and above all, wisdom to navigate the path to the future that is arriving: The Great Simplification.”

So, to conclude, this is, in my opinion, the most important trend of the XXIst century, one that should shape our future — as energy has shaped the XIXth and XXth centuries. Any projection into the future or tentative to forecast anything is incomplete if it doesn’t take this into account. This, of course, is a highly uncomfortable subject, and difficult to accept — for me, it took time to stomach this. Still, it was most useful to accept all of this information in order to move forward. Indeed, without anticipating all of that, how could we even hope to adapt to a low energy world, and save as many people as we can in the process?

Additional resources:

Books:

The very best books I managed to find on this topic aren’t the most technical, but the ones that provide a good overview of the role of energy in history and in our current society. I especially recommend these books, they are very good:

- Reality Blind, by DJ White and Nate Hagens (the book is available for free online!). It is an easy read (quite rare in this domain) that gives a fascinating perspective on how humanity got there and what is happening. One thing I love is that at the end of every section, we get the perspective of TaaL, an alien from a longtermist society who comments on how humans are doing (he’s not convinced!).

- Power - Limits and prospects for human survival, by Richard Heinberg. Why power (or energy) is the most important thing there is, how we obtained so much, and why we are overpowered (read some excerpts there). Chapter 7 explains what actions we can take better than I do. You can also check his Museletter, also a very good read: see this article or this one for some perspective on the current predicament.

- Life after Fossil Fuels by Alice Friedemann, which provides a very good overview of all the challenges at hand and why many alternatives are lacking. The downside is the price, but, well, treat it like a scientific paper (you can also check the author’s website, although things are more messy there). Here is a summary in podcast form.

- The book “Oil, Power, and War” by Matthieu Auzanneau, a complete history of oil, and how it was (and still is) the main driver of our modern times.

Websites:

- Post Carbon Institute and Resilience.org, see for instance this article.

- The Energy section of Our World in Data is a good source of data, as always.

- Our Finite World. The reasoning isn’t always crystal clear, but she has a good perspective on the relationship between investment, oil production and the economy.

- The Great Simplification podcast is really, really good. Check for instance this or this or this episode.

- The International Energy Agency and BP’s statistical review offer a lot of data about current and past trends.

- Thwink.org. If you want to know more about why activists and governments have failed to solve the sustainability problem for 50 years, this seven-year analysis went out to find the root causes of the issue, using a systemic approach and a deep understanding of feedback loops. The crux of the problem we face here is systemic change resistance. I’m uncertain we have the time to implement their solutions but it’s the best analysis I’ve ever read.

I also want to thank all the people who reviewed the post and helped make improvements. The insights of Yvan Denis, Dave Denkenberger and Juan Garcia Martinez were of great importance, the post would have been much worse without them. Thanks also to Siméon Campos, Antonin Broi, Giuseppe Dal Pra, Nicolas Denis, Matthieu Mangeot and Laura Green.

Thank you for this great series of posts, I learned a lot reading them and will dig deeper into some of the references provided! Now, I agree with you that this is probably a very important and neglected topic.

While reading this I had a thought on maximizing utility in this situation. Wouldn't it make sense to prioritize low energy societies now when it comes to building new renewable energy sources? I guess in those societies we still have a chance to substitute all energy that is currently consumed with renewable sources. This would mean those societies wouldn't get into much (further) trouble and could have a rather smooth transition into the post fossil fuel area. Whereas spending most of the resources available for this topic in countries with a high energy consumption seems like an odd choice because here only a small fraction of the necessary energy can be substituted and this probably won't help for a smooth transition.

Glad you found it useful !

As for your suggestion to prioritize low energy societies now when building new renewable energy sources, I think this makes sense. Building a new energy network dependent on fossil fuels probably isn't the best of ideas for these countries, and would smoothen the transition. I had rich countries in mind because that's where I am and have the most data, but that's a good point you're making.

This was a wonderful series of posts. I'm glad I read them!

I'm not an expert in economics and these other fields of study, so I'm sorry if I get anything wrong. That said, the French report on peak oil you cited forecasts that oil production will start to decline around year 2026 (https://theshiftproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/The-Future-of-Oil-Supply_Shift-Project_May-2021_SUMMARY.pdf). And you said that this decline could lead to various negative outcomes like supply chain disruptions and widespread famine. It seems like our societies are short on time.

What do you think needs to happen in order for this kind of famine to be less likely or for supply chain disruptions to be less damaging? How can we figure that out? As you said, people will need ways to provide themselves with the necessary food, water, shelter, medicine, sanitation and maybe other things without a lot of transportation. What are some tractable ways to ensure that, if you know any?

Anyways, thanks for the resources you cited!