This is a guide to publishing research in peer-reviewed journals, particularly for people in the EA community who might be keen to publish research but haven't done so before.

About this article:

- This guide is aimed at people who know how to conduct research but are new to publishing in peer-reviewed journals. I've had a few people ask me about this, so I thought I'd compile all of my knowledge in this article.

- I assume that the audience of this article already: know what academic research is; know how to conduct academic research (e.g. at the level of a Masters degree or perhaps a research-focused Bachelors degree); have a basic grasp of what a journal is; and have the skills to read scientific publications.

- This article is based on my own views and my own experiences in academic publishing. I expect that there will be many academics who have a different view or a different strategy. My own experiences come from publishing in ecology, economics, agriculture/fisheries, psychology, and science communication.

Should you publish your work in a peer-reviewed journal?

Edit: There is also some discussion on this decision in a recent forum article here, and that article's comments too, as well as here.

Advantages of publishing in peer-reviewed journals

- Publication in a journal can make your research appear more credible. This won't always matter, but my colleagues and I have encountered a few instances during animal advocacy where stakeholders (e.g. food retail companies, government policymakers) find research more compelling if it is published in a journal.

- Publication in a journal can make you appear more credible. This is particularly true in non-EA circles, like if you want to apply for research jobs or funding from outside of the EA community.

- Key ideas can be more easily noticed and adopted by other academics, and perhaps other stakeholders like government policymakers. I don't know how influential this effect is.

- Your research can be more easily criticised by academics. This can provide an important voice of critique from experts outside of the EA community, which could be one way to detect if a piece of research is flawed in some way. This is my motivation for publishing a study I conducted where I used an economic model to estimate the impact of slow-growing broilers on aggregate animal welfare - submitting a paper like this for peer review is a great way to get feedback from experts in that specific branch of economics.

Drawbacks of publishing in peer-reviewed journals

- Publications are not impact. Publishing your work is a tool that can sometimes help you to achieve impact. If we're trying to do the most good in the world, that may sometimes involve publishing peer-reviewed research (see above). In other cases, it'll be better to spend that time on more impactful work.

- Not all research is suitable for peer-reviewed journals. For example, in the EA community, it is common to conduct prioritisation research to determine the most promising interventions or strategies, like our recent work on fish advocacy in Denmark. That fish advocacy report would only be interesting to advocacy organisations and doesn't contribute any new understanding of reality beyond the strategy of one organisation, so it is probably not be publishable in a journal (though a smaller version focused on the Appendix of that report may be publishable).

- Publishing in peer-reviewed journals costs time and energy. When I publish in a peer-reviewed journal (compared to when I publish a report on my organisation's website), I usually spend a couple of extra days writing the draft, and then a few extra days addressing peer review comments over the following months.

- Peer-reviewed papers have significantly longer timelines. After the first draft of a manuscript is done, it might take 6 or 12 months or even longer (most of which is spent waiting) before the article is finally published.

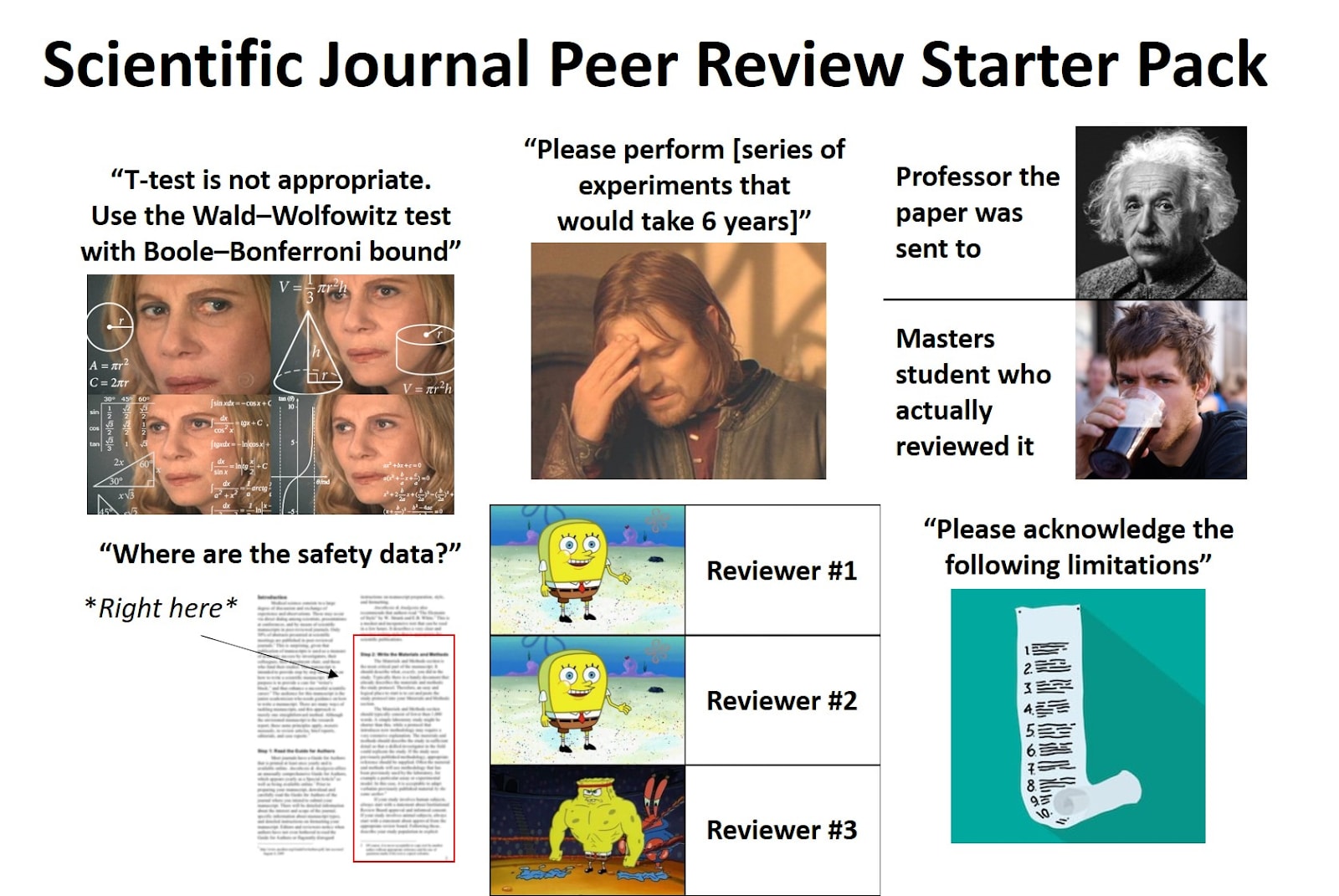

- Peer review can be emotionally challenging (see below).

- Peer review does not guarantee quality research. In the experience of myself and probably most academics, peer review does, on average, increase the quality of papers (1). That said, there are lots of examples of obviously low-quality and non-rigorous studies in peer-reviewed journals (including one or two of my own!). There are also lots of examples of rigorous, top-notch pieces of research published outside of peer-reviewed journals (including many posts on the EA Forum). Publishing is not a panacea, but it can be a tool to help you achieve impact.

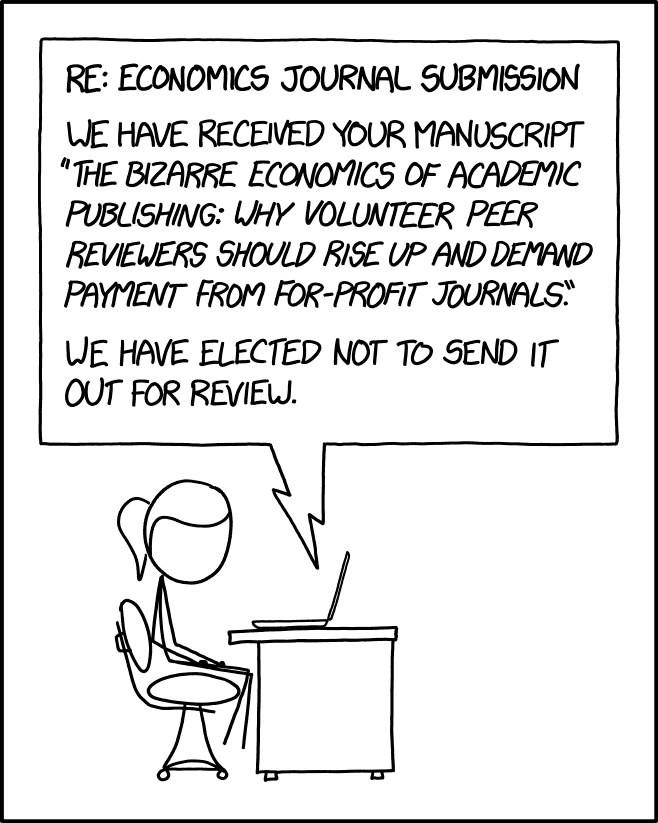

- It's no secret that the peer review system and the publishing industry have major challenges. Major issues include the replication crisis; extremely high numbers of publications being churned out each year; discrimination; uncompensated labour by peer reviewers and editors; shady, questionable practices such as p-hacking; outright fraud such as data fabrication; and predatory journals. There is lots of information about all of these available online. The publishing industry is not perfect, but it can help you achieve impact.

How peer-reviewed papers differ from EA Forum articles

- Compared to EA Forum articles, peer-reviewed papers are more detailed in the literature that they cite. Typically, when you're writing a paper, you need to demonstrate a deep, detailed understanding of the peer-reviewed literature relevant to your research. It is common for papers to have even 60 - 100 references, though many shorter papers have fewer. For one of my peer-reviewed papers (a short opinion article), I read roughly 50 papers and cited 15 of these. For another one of my papers (a long review article), I read roughly 400 papers and cited 100 of these.

- Peer-reviewed science tends to be more focused on testing ideas and theories, not having impact. This means that the focus of the papers tends to differ from the focus of EA Forum articles, though it is still very possible to publish a high-impact piece of research in a journal. It's just important to understand this difference to make sure you're pitching your work in the right way when writing and submitting to a journal.

- Peer-reviewed papers are written in a different tone and style. The main differences from an EA Forum article are a) the academic writing style (see below), and b) the use of in-text citations rather than links to sources.

How I think about publishing

- I hold two beliefs: 1) publishing is a game, and a pretty silly game at that; 2) you can publish any piece of research, as long as the paper is at least passable in quality.

- It is very common to have a paper rejected by one or multiple journals before having it accepted by another journal (2–4). One small survey found that it was normal for authors to submit papers 4 times before being accepted, with one author reporting a paper that was submitted 11 times before finally being accepted (4)! While this sometimes means that the paper is eventually accepted by a less prestigious journal, many papers are actually accepted by more prestigious journals (3). I have had opinion articles accepted by PNAS and Trends in Ecology and Evolution, both pretty swanky journals, after being rejected by less prestigious biology journals.

- There is a pretty low level of agreement between individual peer reviewers (5), and there are many, many journals. If reviewers don't like your paper and it gets rejected from one journal, there is every chance that the paper will be appreciated by another set of reviewers from another journal.

- Authors, reviewers, and editors are not gods - they are simply nerds with laptops, just like the rest of us.

- Therefore, if your work is at least passable in quality and rigour, the chances of achieving publication are pretty high as long as you persist in submitting to new journals.

- Under this cynical view of the publishing industry, the most important skill is not necessarily to produce quality research - rather, the most important skill is to cultivate "rejection resilience" (4). Of course, we also have a responsibility to produce high-quality, rigorous research, but this is not always a requirement for actually publishing your work.

Types of journals

A quick Google tells me that there are around 30,000 to 50,000 peer-reviewed journals currently in existence. The database Journal Citation Reports lists over 21,000 journals. Even once you narrow this down to journals that would accept a particular paper, you still might be looking at hundreds or even thousands of journals that you could plausibly target. Here is one way to think about the different journals out there - this is just how I think about journals, and this is not a comprehensive or exhaustive system. Note that the first four categories overlap.

Top-tier journals

Firstly, there are the really swanky, top-tier journals. These are highly prestigious. Think Nature, Science, and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). These typically have Impact Factors of above ~10, and sometimes above 30. Those three journals publish articles across a variety of disciplines, but there are also many top-tier journals that are specific to certain fields.

High-tier and mid-tier journals.

Secondly, there are high-tier and mid-tier journals. These are the standard, bread-and-butter journals, where most academics will publish most of their work - they are perfectly respectable places to publish. Depending on the discipline, these may have Impact Factors between 0.5 and ~10. In biology, this might include Global Change Biology, Marine Biology, Fisheries Research, and Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. In economics, this might include Environmental and Resource Economics or Journal of Labor Economics.

Low-tier journals

On the less prestigious end are low-tier journals, which usually have an Impact Factor below 1. These can be perfectly rigorous journals, but are often focused on a very specific region (e.g. Journal of the Adelaide Botanic Gardens; Icelandic Review of Politics & Administration) or a very specific topic (e.g. American Malacological Bulletin). These can be a good place to publish if you a) care about your work being published, b) do not care about the reach of your paper or prestige of your journal, and c) have already tried a few high- and mid-tier journals.

Open-access mega journals

Open-access mega journals are a relatively recent phenomenon. These journals tend to have some unusual characteristics: they publish very large numbers of papers; they often don't care about the novelty of a paper, but will accept the paper as long as it is rigorous and passes peer review; and they charge the author a fee for publishing (6). They'll only really reject if the work is actually low-quality or unscientific. But the trade-off is that they do charge quite large fees for publication (from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars, depending on the journal and the type of article). You may be able to apply for a fee waiver or discount if you're from a developing country and/or if you do not belong to a university or institution. Often, a single publisher owns a large number of these journals.

Major examples include the publishers Frontiers (e.g. Frontiers in Psychology), MDPI (e.g. Animals), and other journals like PeerJ and PLOS ONE. Note that open-access mega journals do conduct rigorous peer review and are therefore not predatory journals (see below). I quite like these journals, and they tend to be open-minded, but I wouldn't exclusively rely on them - some academics are wary of publishing only in open-access mega journals, and it is not always possible to fork out $2,000 or more for a publication fee.

Journals that work differently

There are a few interesting journals that I want to flag here. F10000 Research is an open-access mega journal that publishes before peer review - then, peer review comments are made public, and the authors can adopt the comments into a revised paper that is published in place of the old one (though this journal charges publication fees). Journal of Controversial Ideas is notable for allowing anonymous publication. Depending on the field, there are also some journals that explicitly invite replication studies or null results.

Places to publish your research that are not journals

Depending on your motivations for publishing, there are places you can publish your work that aren't actually peer-reviewed journals, but share some characteristics of journals. For example, see The Unjournal. I'd include the EA Forum in this category. I'd also include pre-prints, but I'll discuss these more later in this article (see below).

Student journals

There are some journals, often affiliated with specific universities, that specifically publish papers from undergraduate students or graduate students. I'd usually stay away from these. While these journals are typically rigorous, they also tend to have low prestige and small audiences. I think most papers that are publishable in student journals are also publishable in mainstream journals.

Predatory journals

Unfortunately, there are many predatory journals out there. These journals either don't conduct peer review, or conduct a minimal peer review as a simple formality. These journals often charge for publication. If you look online, you can find many lists of predatory journals and predatory publishers, and there are guides to help you evaluate if a journal is predatory (e.g. Beall's List). Stay far, far away from these.

Types of papers

There are a number of different types of papers that can be written and submitted to journals. Not all journals accept all of these types, and different journals have different definitions - make sure you check the "instructions to authors" page of the journal.

- Research articles. This forms the bulk of published research. These are empirical studies based on original data. They typically fall in the range of 4,000 to 10,000 words, depending on the journal.

- Short reports. Some journals accept shorter research articles. These are also empirical studies based on original data, but they are shorter in length. They typically fall in the range of 1,000 to 6,000 words, depending on the journal. This can be appropriate for publishing pilot studies or any other study that does not need to be a full research article. These are surprisingly high value - they are faster to write, are faster to get through peer review, and often just as impactful as full-length research articles.

- Review articles. These are literature reviews. These range from glorified opinion articles, to narrative reviews, to systematic reviews, to systematic reviews accompanied by meta-analyses.

- Opinion / perspective articles. Some journals accept opinion or perspective articles (these often have creative names, like the "Science & Society" article type in Trends in Ecology and Evolution). These are also critical, rigorously researched, and well-supported by existing literature, but they can often present a particular viewpoint. These usually don't involve any data or empirical analysis. It is sometimes possible to publish opinion or perspective articles that rely on a small empirical analysis or a pilot study, as long as it is presented in the right way.

- Reply articles. Many journals let authors write short replies that respond to other authors' publications in that journal. These can offer agreement and extend on the original paper, or they can be critical and point out flaws. Paper fights!

Choosing journals to target

Edit 23rd March 2024: I've just found JournalGuide and SciRev which seem like useful databases of journals that let you filter by discipline and then sort by both impact factor and publication speed. Seem like really useful tools for picking journals.

These are the main considerations when considering journals:

- (Essential) Does the journal have an article type that matches the type and style of paper that you're aiming to write? You can see this on the "information for authors" page on the journal's website.

- (Essential) Does the journal's scope seem like it'd include your paper? Has the journal published papers like yours before? Some journals are very narrow in what they're interested in, while others are much more open-minded.

- (Essential) Does the journal have fees? This is pretty common for open-access journals. There are so many journals in existence that you'll be able to find many without fees.

- (Helpful but non-essential) What is the journal's impact factor? I've just found this site, which seems to list all journals and their impact factors. You probably wouldn't want to go below an impact factor of 1 (though it is more common for journals in the humanities to have lower impact factors, even if they're swanky journals). Bigger is better (mostly). But journals with impact factors that are too big (above ~10-15ish) also have very high rejection rates. So I reckon impact factors of between ~2.0 and ~8.0, based on my gut feel, would be the sweet spot for many science and economics papers.

- (Helpful but non-essential) Does the journal have an international focus, rather than a local focus? (See "Low-tier journals", above). If you're interested in credibility and career capital, it might be worth picking a journal with an international focus (and therefore a stronger reputation).

- (Helpful but non-essential) Does the journal have a name that will look relevant on your resume? For example, if you want to get into a job in economics, it probably wouldn't hurt to have the word "economics" in the journal title.

There are some strategies:

- Make a list of between 3 and 10, guided by the above criteria. Make sure they have a section that fits your type of article and your word count. Pay attention to whether they charge Article Processing Charges or page fees. Ideally, your list will consist of mostly high- and mid-tier journals, though you can also include a few low-tier journals and open-access mega journals if you feel like it. Be prepared to modify this list after you receive feedback on your paper.

- You can only submit a particular paper to one journal at a time, but having a list makes it easier to submit your paper to a new journal if it gets rejected.

- Some people simply start at the highest tier journals (Nature, Science, and so on) and then work their way down the list. This isn't a bad strategy (2). It is good to be ambitious (don't sell yourself short!). However, it is also good to be honest with yourself about whether a particular paper has any chance of getting into Nature or Science so you can save yourself time and energy.

- Most research questions would fit well in multiple disciplines. For example, a paper on intensification of agriculture in India might fit into journals in agriculture, agricultural economics, international development, poverty economics, animal welfare, food security, or possibly even environmental sustainability.

- You can find information by searching Google, and for many fields you can find blog articles online that make recommendations. If you know which existing papers are similar to yours, you can look at where those papers were published. If you are affiliated with a university, you might have access to tools like InCites Journal Citation Reports. (Edit 23rd March 2024: Also see JournalGuide and SciRev)

- Over time, you develop a feel for which journals accept which type of work. For example, not all entomology journals will be keen on insect welfare research, but other journals will find that very swanky.

Coauthors

- If you've conducted a study as part of a team, then it is typical for the people who have contributed to the study to be listed as co-authors on the paper. This might include people who helped with data collection and analysis; people who contributed in other important ways, like designing the study and helping to write the paper; and supervisors. The person who did the bulk of the "work" on the paper is usually the first author, though this is not always the case (e.g. some fields list authors alphabetically). Ideally, authorship and author order would be determined in advance.

- It's not always clear-cut who qualifies for authorship. If somebody has helped out in a small way, it may be more appropriate for them to be listed in the "acknowledgements" section of the paper rather than as a coauthor. There are lots of guides on the internet if you need help figuring this out.

- Coauthors will always need to approve the manuscript before it is submitted for publication (and you need to confirm that this has happened when submitting). Therefore, disputes or fallouts between coauthors will typically mean that the paper is unable to be published.

- Having senior coauthors (e.g. professors or well-known academics) can help lend your paper credibility, and these coauthors will often have lots of experience going through the publication process themselves.

Steps for writing and submitting a paper

Your guidebook is the "instructions for authors" or "guidelines for submission" page of the journal, which you can find on the website of any journal. That page is the single most important document to read, understand, and follow to the letter. Pay close attention to it, and do exactly what it says.

Writing the paper

- I assume that you already know how to conduct research and that you know what a journal article looks like (e.g. structure, academic tone). There are guides available that can help you with those things too.

- In terms of writing style, there are two schools of thought. The book Writing Scientific Research Articles: Strategy and Steps by Cargill and O'Connell is a great general introduction to academic writing. The work of Helen Sword and the book The Sense of Style by Steven Pinker expand on the academic style by adding style and flair. If you're not yet comfortable writing in academic language, I'd stick to the first option. If you have experience and want to improve the reach of your paper, it may be worth exploring the second option.

- Emphasise the global relevance and policy implications of your research, particularly in the abstract, introduction, and discussion. Often, your research will involve a particular local area (e.g. you might use a particular country or state as a study location, or a particular species as a study species), but it's often wise to hold off on the details of this until the beginning of your methods. A colleague is working on a study about wealth and intensification of animal agriculture in India, but the focus of the paper is on the theory of wealth and agricultural intensification; India is presented as a study site, not mentioned until the methods section of the paper. Likewise, one of my PhD chapters was a study about cooperative management of a shellfish fishery in south-east Australia, but I pitched the chapter as "extending the economic/game theory of fisheries management to account for climate change and environmental fluctuations".

- If you have difficulty writing or editing your English, there are paid proofreaders who can help. Just make sure you pay attention to the journal's policies on paid proofreaders/writing assistants - they often need to be acknowledged in some way.

Parts of a journal submission

When you submit a paper, you also need to submit a bunch of other stuff:

- The manuscript itself. This is the main file containing your paper. If the "instructions for author page" doesn't give you specific instructions, it's standard for this file to be formatted with double spacing, size 12 Times New Roman font, page numbers, and sometimes line numbers. There are templates here if you want, but make sure to follow every instruction in the "instructions for author" page.

- Figures and tables. These are sometimes included at the end of the manuscript file, or otherwise uploaded as separate files. It depends on the journal.

- Title page. This lists the title of your paper, author names, author affiliations, and sometimes extra statements or other information (depending on the journal). Use this guide, and follow any extra instructions on the "instructions for authors" page of the journal you're targeting. Some journals want the title page as a separate file (especially if they conduct double-blind peer review), while others want the title page as the first page of the manuscript.

- Cover letter. Not all journals require these. This is a document whose purpose is to convince the editor to send your paper to peer review. It should, very briefly, address the editorial board, give the title of your paper, state what your research has done, and explain why your paper is interesting and worth publishing. Be brief and compelling. The cover letter itself is not peer reviewed, so some academics embellish the truth a bit to spark the editor's interest. It's great if you can write a cover letter on a university letterhead and have it signed by an author with a title (e.g. if you or a coauthor have a PhD or are a Professor), though that's not essential. Use this guide.

- Various statements. Depending on the paper and the journal, you might need: a conflict of interest statement; a data availability statement; an ethics approval statement; an author contribution statement; and an acknowledgements section. These are all quick and easy, and there are examples you can copy or closely follow online.

- Data and code. Some journals let you upload your data and code for review, or otherwise submit it to a data repository for public access once your paper is published. Even if you're not going to publish your data and code, make it as replicable and easy to understand as possible. This is for your own sake - it'll save you headaches when you need to make subtle adjustments to your analysis due to peer review comments, six months after you last thought about the paper. It's also polite to cite the software and any additional software packages you use (e.g. R packages).

Author name

If it's your first submission, you'll need to figure out which name you want to publish under. Typically, this will be your full name. I'd encourage you to add your middle initial, or even your full middle name if your name is common. The idea is to have as many individual unique letters in your name as possible, to avoid being confused with other researchers in the future - it does happen.

Also consider if you're planning to change your name in the future, perhaps for marriage, gender affirmation, or religious reasons. It is possible to change your name on a published paper, but it's just a bit of extra bureaucracy that's best to avoid if possible.

Pre-submission enquiry

Some journals use pre-submission enquiries, and don't allow journal submissions unless you've already sparked the editor's interest with a pre-submission enquiry. This is basically an email, addressed to a particular editor, pitching your idea. This is very similar to a cover letter. Pre-submission enquiries are more common in swanky journals (e.g. Nature, Science) or review articles in high-tier journals.

Submission portal

Basically all journals use a submission portal to manage the submission process. You get to the submission process by clicking the big shiny "Submit a paper" or "Submissions" button on the journal website. You'll usually need to register for an account, and some journals require you to enter an ORCID (ORCIDs take ten seconds to make if you don't have one).

The portal will have a very structured way to submit your paper. You'll need to upload all your files in the right spots, in the right way. You'll also need to enter a bunch of information about your paper (e.g. your name, coauthor names, title, abstract, word count, number of figures and tables).

Some journals allow, or even require, you to recommend peer reviewers. Other journals forbid this. The point of recommending reviewers is to save the editors time, as authors typically have the best idea of who the experts in their discipline are. Editors will not always use your suggested reviewers, but they often will. Some authors will specifically choose reviewers who are likely to look on their work favourably (e.g. if the reviewer shares a philosophical view or theoretical perspective with the author). You cannot recommend reviewers if you have recently worked with them or if they belong to the same university/institution as you.

Do not communicate with the journal outside of the submission portal, unless you've been specifically asked to do so. Editors are highly time-stressed, and this will mostly annoy them. Keep communications to essential information within the portal, and keep any communications brief.

After submission

Possible outcomes

After you've submitted a paper to a journal, there are four main outcomes:

- Desk reject. This is when your paper is rejected by the editor, without being sent to peer review. This is usually because the paper doesn't fit into the scope of the journal or because the editor just plain doesn't like it. Desk rejects are common. (Sometimes you also have a paper returned before it is sent to the editor, because an administrator has spotted formatting errors or something like that.)

- Reject after review. This is when your paper is sent to peer review, and then rejected by the editor due to the peer review comments. This is also fairly common. If you take the comments on board (see below), it hopefully shouldn't happen too many times for a given paper.

- Revise and resubmit. This is when your paper is sent to peer review, but the editor/peer reviewers have requested changes to the paper. You have the opportunity to revise the manuscript in line with the reviewer comments (see below), and then resubmit to the same journal. This is a great outcome - it means the editor seems interested and thinks that it could plausibly be published in the journal. Depending on the journal and how major the revisions need to be, the revised manuscript might be evaluated by the editor, by the same peer reviewers, or by different peer reviewers.

- Accept. If the editor thinks your paper is high-quality and appropriate for the journal, and if the paper passes peer review, then it can be accepted by the journal. Acceptance without any revisions is quite rare - it is much more common to go through at least one round of "revise and resubmit" before a paper is accepted.

Timelines

The time it takes to publish a paper strongly depends on the journal and the discipline. Many journals list their median publication times on their website. It is common to take a journal a few days or weeks to either desk reject or send the paper to peer review, and it is common for peer review to take several months. After a paper is accepted, it might take a few weeks to be published on the journal's website, though it might be uploaded as an unformatted manuscript to the journal's website in the meantime.

Addressing peer review comments (revise and resubmit)

A top-notch guide is the paper by Sullivan et al (7), which gives step-by-step advice for responding to peer review comments. Follow their advice. I would emphasise their key points:

- "Answer every request or question, but use no more words than necessary."

- "Make your author response letter crystal clear—as clear yet as brief as possible. [...] Brevity is a virtue, yet your responses must be complete."

- "The editors and reviewers are (nearly) always right."

You might not agree with all of the comments. It is common for peer review comments to be silly or even nasty. As Peterson (8) writes: "Dear Reviewer 2: Go F’ Yourself". Nevertheless, if you want your revised paper to be accepted by that journal, you must take all of the comments on board and adopt them all, to the best of your ability. In the case of misunderstanding, adopting a comment might not mean doing exactly what the comment says, but rather figuring out why the reviewer might have become confused and then clarifying your manuscript to avoid that misunderstanding. In practice, I've found it's usually safe to respectfully disagree with 1 comment for every 10 or 20 comments that I do adopt without complaint. (In the case of actual abuse or discrimination by the reviewers, which sadly does happen, things are different - see the below section on discrimination.)

Addressing peer review comments (reject after review)

If your paper is rejected after peer review, meaning you need to submit your paper to a new journal, then you don't have such a strong need to adopt the comments from that peer review. However, it can be good to consider the comments and adopt the comments that seem valid, major, and/or easy. This can stop you from tripping up over the same problems with the next journal.

Proofs (after acceptance)

After your paper is accepted, the journal will typically send you proofs - this is the formatted paper, in line with the journal's style. You'll get a link to an online portal, where you can correct any formatting/visual mistakes and respond to any questions from the typesetter and production staff.

When to quit

If you come to see your paper as genuinely flawed, faulty, or non-rigorous, then it is ok to quit and not worry about publishing it. Try not to confuse this with thinking that your paper is flawed because a peer reviewer said so.

Emotional challenges

Rejection resilience

Rejection is ubiquitous. Every academic on the planet routinely experiences rejection (9). It really sucks to have your work rejected. Whenever I check my emails and see that a journal has sent me a rejection letter, it stings. My cheeks burn and my stomach drops. I've learned to accept this feeling more quickly as I've developed as a researcher, and I'm less averse to rejection since I've developed lots of experience.

My view is that to publish papers, the most important skill to cultivate is "rejection resilience" (4). If you persist, and your work is at least half-decent (i.e. it is rigorous, it engages with the existing literature, and it is not downright fraudulent), then the chance that your work will eventually get published is high.

A satirical, but validating, perspective on rejection is provided by Han et al (10), who describe "ManuScript Rejection sYndrome (MiSeRY)": "Manuscripts associated with high pre-submission expectations and sent for external review were associated with increased MiSeRY when rejected. This was especially true for first authors, who are not only more personally invested in the reported research but must also bear the burden of re-formatting the manuscript for the next submission. Further, we hypothesise that senior authors, who have undoubtedly encountered MiSeRY during their formative research years, may have developed enhanced Coping and reLaxing Mechanisms (CaLM) that guard against a potential state of permanent MiSeRY."

I think Han et al demonstrate a great mindset for publishing. As they write: "We acknowledge the various medical journals that have rejected our manuscripts and provided inspiration for this study. To quote a contemporary poet: 'thank u, next'."

One particular complication that I've experienced due to rejection is email anxiety. As Gill (11) writes, "'Addiction' metaphors suffuse academics’ talk of their relationship to e-mail, even as they report such high levels of anxiety that they feel they have to check e-mail first thing in the morning and last thing at night, and in which time away (on sick leave, on holiday) generates fears of what might be lurking in the inbox when they return." In my own case, this has been exacerbated by previous experiences and psychological challenges (including trauma and abuse during my childhood and adolescence). Developing emotional intelligence, self-understanding, and mindfulness, as well as understanding what my core values are, have been really useful in learning to manage this anxiety (probably good life advice in general, if somewhat inane!).

Reviewer comments can be nasty

It's no secret that peer reviewers can sometimes be really mean (12). While many peer reviewers are helpful and encouraging, others can be downright nasty (often partially because they have experienced hurtful criticism or other injuries from academia themselves).

Gill (11) reports receiving this reviewer comment: "This paper will be of no interest to readers of x (journal name). Discourse analysis is little more than journalism and I fail to see what contribution it can make to un- derstanding the political process. It is self evident to everyone except this author that politics is about much more than 'discourse'. What’s more, in choosing to look at the speeches of Margaret Thatcher, the author shows his or her complete parochialism. If you are going to do this kind of so-called 'analysis' at least look at the discourse of George Bush."

Gill also tells us how she responded: "I laughed (bitterly) at the accusation of parochialism from this particular North American journal, and even more at the suggestion that this would be put right by focusing on the US (!). But that was small comfort because mostly I felt belittled, hurt and upset at this dismissive rejection of work that I had thought about, developed and crafted over months of careful scholarship. Maybe I wasn’t 'good enough' for academia. I had felt optimistic and proud to have written my first 'proper' academic paper. Eight months later when the rejection letter came, disheartened, I could not bear to look at it again. It remained unpublished and some years passed before I submitted another paper to a journal."

Burnout and discrimination

Burnout is common among academics. The publication system has contributed to this (9).

Since reviewers are human, comments can even be straight-up sexist, racist, transphobic, ableist, and/or offensive in other ways (13,14). There's a discussion of this here. Depending on context, some journals and universities have complaints policies (though I'd be skeptical about their value).

Tips

- Use a reference manager. These are programs that store all of your papers (both the citation information, e.g. author, date, title, etc, + you can attach the full-text PDF). This will save you many, many headaches (you'll find yourself storing hundreds or maybe even thousands of papers if you get into research over the next few years). My #1 recommendation would be Zotero (free), and #2 would be Mendeley (also free). Paperpile is also really good. Endnote is popular, but I think it has a difficult workflow. Spend a bit of time (perhaps an hour) learning how to import references - it'll be time well-spent. Also, get the browser plugin for whichever reference manager you choose. Then when you find a paper you like, it's one click to import it to your library (plus sometimes a bit of extra work for importing PDFs, but this is reduced if you use Zotero, Mendeley, or Paperpile). Also, get the word processor plugin for whichever one you choose. Probably working in Google Docs would be easiest if we're collaborating. I think Zotero has a Google Docs plugin. This automatically formats your reference list, can one-click change the formatting of your references, etc. Absolute miracle.

- Make sure you're engaging with the literature that is relevant to your study. You definitely need to cite the seminal, key publications in your field (e.g. review articles, important books, seminal papers). You also need to cite any other papers that are relevant to your topic, research question, your study site, or your methodology. It's common for a research article to have between 30 and 60 citations.

- Do not publish your paper anywhere online (including the EA Forum) if you plan to submit it to a journal. The exception is preprints (next point).

- Consider publishing your work as a preprint. There are many places online where you can "publish" your draft manuscript at the same time as submitting it to a journal. This lets you share your work with others (by linking to the preprint) without waiting for the peer review process. Do pay close attention to the preprint policy of your target journal - most journals have no problem with you posting your work as a preprint first, but some journals differ. Good preprint servers include https://biorxiv.org/, https://arxiv.org/, and those hosted by Open Science Framework. Most disciplines have specific preprint servers.

- Consider academic conferences, or don't. Academic conferences are one way to "publish" your work. Some conferences actually publish your full paper in a large document that contains all of the papers presented at that conference. Other conferences simply invite people to present work they're planning to publish elsewhere. Conferences are very important in some fields (e.g. computer science). Conferences are also good if you want to network with academics in a particular field. Apart from that, I've found them to be a waste of time (talking about academic conferences here, not EAG). If you're presenting your work specifically as a poster, then I strongly encourage you to watch the Better Poster videos and ignore all other advice you receive on creating your poster.

- I've heard people claim that an editor might be more willing to consider your paper if you or a coauthor are from a university, or if you or a coauthor have an academic title (e.g. PhD, Professor). This isn't strictly necessary, but I suspect it can help.

- Stay away from ChatGPT. Most journals explicitly forbid the use of large language models when writing your paper, and sometimes in other aspects of the research too.

Suggested reading

The Lean PhD by Julian Kirchherr

- This is targeted at PhD students, but much of it is highly relevant to publishing.

- Chapters 1 and 3 have most of the value. Much of this strongly aligns with my own views, such as: "You do not want the paper to be perfect; you want it to be a minimum viable paper, since reviewers will always provide plentiful comments on any paper, no matter how excellent it already is." ... "Peer review can almost be as random as a coin toss."

- A lot of what the author describes is how to "play the game" (as I have also done in this article!) - which is perfectly valid, but of course there is also the responsibility to produce research that is not only publishable but actually high-quality and potentially impactful. I think the author does explicitly say that too.

- I don't agree with everything the author says or does. It seems like some of the strategies they recommend could lead to taking advantage of people, though this is more relevant for people in positions of power who already know how to publish.

- Concretely, I disagree with the author's approach to responding to peer review comments. They say "I really develop in-depth responses to every single comment raised by my reviewers in my revision process." This strikes me as unnecessary - the author mentions having once written a 26-page response letter to reviewers, which is something I would never do. My approach still incorporates all reviewer comments, of course, but I prefer much more succinct response letters (see above). Even if you make extensive changes to your manuscript, the response to the reviewer can just summarise these changes and give the page/line numbers. This is a good reminder that every academic, including me, will have their own individual approach.

Books on academic writing style

- Writing Scientific Research Articles: Strategy and Steps by Margaret Cargill and Patrick O'Connor (if you're new to academic writing, start with this book)

- Air & Light & Time & Space: How Successful Academics Write by Helen Sword (once you have a bit of experience writing)

- The Sense of Style by Steven Pinker (once you have a bit of experience writing)

References

1. Kharasch ED, Avram MJ, Clark JD, Davidson AJ, Houle TT, Levy JH, et al. Peer Review Matters: Research Quality and the Public Trust. Anesthesiology. 2021 Jan 1;134(1):1–6.

2. Salinas S, Munch SB. Where should I send it? Optimizing the submission decision process. PLoS One. 2015 Jan 23;10(1):e0115451.

3. Calcagno V, Demoinet E, Gollner K, Guidi L, Ruths D, de Mazancourt C. Flows of research manuscripts among scientific journals reveal hidden submission patterns. Science. 2012 Nov 23;338(6110):1065–9.

4. Allen KA, Freese RL, Pitt MB. Rejection Resilience—Quantifying Faculty Experience With Submitting Papers Multiple Times After a Rejection. Acad Pediatr [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://www.academicpedsjnl.net/article/S1876-2859(21)00649-5/abstract

5. Bornmann L, Mutz R, Daniel HD. A reliability-generalization study of journal peer reviews: a multilevel meta-analysis of inter-rater reliability and its determinants. PLoS One. 2010 Dec 14;5(12):e14331.

6. Spezi V, Wakeling S, Pinfield S, Creaser C, Fry J, Willett P. Open-access mega-journals: The future of scholarly communication or academic dumping ground? A review. Journal of Documentation. 2017 Jan 1;73(2):263–83.

7. Sullivan GM, Simpson D, Yarris LM, Artino AR Jr. Writing Author Response Letters That Get Editors to “Yes.” J Grad Med Educ. 2019 Apr;11(2):119–23.

8. Peterson DAM. Dear reviewer 2: Go F’ yourself. Soc Sci Q. 2020 Jul;101(4):1648–52.

9. Jaremka LM, Ackerman JM, Gawronski B, Rule NO, Sweeny K, Tropp LR, et al. Common Academic Experiences No One Talks About: Repeated Rejection, Impostor Syndrome, and Burnout. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2020 May;15(3):519–43.

10. Han HC, Koshy AN, Lin T, Yudi M, Clark D, Teh AW, et al. Predictors of ManuScript Rejection sYndrome (MiSeRY): a cohort study. Med J Aust. 2019 Dec;211(11):511–3.

11. Gill R. 17 Breaking the silence: The hidden injuries of the neoliberal university. In: Secrecy and silence in the research process. Routledge; 2013. p. 228–44.

12. Mavrogenis AF, Quaile A, Scarlat MM. The good, the bad and the rude peer-review. Int Orthop. 2020 Mar;44(3):413–5.

13. Strauss D, Gran-Ruaz S, Osman M, Williams MT, Faber SC. Racism and censorship in the editorial and peer review process. Front Psychol. 2023 May 19;14:1120938.

14. Cochran A. Gender Discrimination in Peer Review [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/d2kz9

Preview image by JJ Ying (@jjying) on Unsplash

As another published academic, I'll add another downside and another upside:

My downside is that the tone of academic articles tends to incredibly dry. Humour and conversational tone are not unheard of, but are generally frowned upon, and it can make papers a bummer to read and write. Casual audiences will be less likely to read your work as a result. To remedy this, it might be worth doing a summary post of your work that is more accessible to general audiences.

My upside is that peer review really forces you to engage with the existing literature on a subject. Yes, this is often time consuming and painful (which is why most people wouldn't do it otherwise), but it a) forces you to back up your claims, and b) forces you to check what's actually been done before. EA (and especially Rationalists) can have a bad habit of not invented here syndrome, reinventing the wheel when very smart people have already spent years working on a subject.

It gets paid back as well: next time an academic is looking at the same subject, they are forced to consider your research and perspective, and may add or expand on it in a way you never thought to do.

Just a quick note as The Unjournal was mentioned. We commission expert peer review and rating (and pay the evaluators) and all evaluation is made public. We focus on potentially-impactful work in economics, social science, and policy. We are aiming at a standard and metrics that will be comparable and can be benchmarked against the traditional journal tiers, as well as ratings and adding value on other dimensions.

Submitting your work to The Unjournal basically does not preclude you from also submitting it to anywhere else. We don't 'publish' your work or claim ownership of it; you need to have it made available publicly (in an archive, working paper series, etc., we can advise on this if you like). We simply evaluate it.

Anyways, this is all stated better in our 'nutshell explanation', and our 'why should authors engage' and on our page (unjournal.org), which has an enabled chatbot you can use to ask it questions.

Executive summary: This comprehensive guide provides advice on publishing research in peer-reviewed journals, particularly for newer researchers, covering decision-making, types of journals and papers, writing and submission steps, addressing reviews, and managing rejection.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Thank you for this, Ren! I really appreciate it.

One tip I would suggest is to consider trying to find template(s) to follow for any new research project. That is, try to find one or more papers which address the same topic and/or use the same method as your paper, before you start on the paper. The best case is if the templates are published in the journal/outlet you are targeting.

When you have templates, use them to guide and simplify the production of your paper. For instance, this might be by closely following the method, structure, style of diagrams, sections or paragraphs etc in the template. Or by rewriting an existing but similar section (e.g., the abstract or conclusion) rather than starting one from scratch.

Often you can basically reuse arguments and references. For instance, if you are trying to claim that Animal welfare is important in context x, and a published paper has a paragraph arguing for that, then you can often just rework that paragraph and cite the same references rather than spend time trying to find your own references and construct new arguments etc.

You also reduce a lot of risk by building on something that was accepted after a lot of revision and work, rather than trying to implement your naïve best attempt at what would be acceptable etc.

Found this really helpful- thanks for sharing Ren, along with great summary tips!

Thank you for sharing this!

Thanks Ren for this in-depth article. This is pure gold! Btw: I happened to read something related a couple of days ago: why-you-should-publish-your-research-in-academic-fashion. Maybe you should ask the author to link to your post?

Also: You have written "paper" instead of "journal" on the first line of your subsection Open access mega journals.

Thank you, fixed.

I did search for related articles on the EA Forum before posting mine, but I missed that one. The irony!! I'll add a link to that post in this article.

Thanks, very good article ! This might prove helpful in the future, who knows.