1. Introduction

Should we expect the future to be good? This is an important question for many reasons. One such reason is that the answer to this question has implications for what our intermediate goals should be. If we should expect the future to be good, then it would be relatively more important for us to focus on ensuring that we survive long into the future, e.g. by working on mitigating extinction risks. If we should not expect the future to be good, then it would be relatively more important for us to focus on mitigating risks of astronomical suffering.

In this paper, I critique Paul Christiano's (2013) argument that the future will be good. In Section 2, I reconstruct Christiano's argument in premise form and articulate some simplifying assumptions which I later relax. In Section 3, I offer a model for exploring the composition of different groups in a population over time. In Section 4, I show that, when certain assumptions are made, the model can generate the kind of favourable result that Christiano seems to have in mind. In Section 5, I show that, when fanatics are included in the model, a favourable result is no longer guaranteed. In Section 6, I consider that different groups can have different levels of influence whilst having the same number of adherents (i.e. members or followers), and argue that we should be far from confident that those with our values, as opposed to fanatics, will disproportionately influence the future. In Section 7, I argue that, even in the absence of fanatics, we should be sceptical that those with our values will disproportionately influence the future. In Section 8, I argue that, even if those with our values disproportionately influence the future, it is unclear that they will successfully make the future go well. In Section 9, I conclude by situating this paper as part of a broader argument that we are in a position of deep uncertainty regarding whether the future will be good, by which I mean that we lack a principled way of assigning precise probabilities to the proposition that the future will be good, due in large part to the presumably vast number of parameters, many of which are currently unknown to us, that will collectively shape the future through their complex interactions.

2. Christiano's argument

In his post, titled 'Why might the future be good?', Paul Christiano (2013) argues that the future will be good. His argument can be decomposed into three premises and a conclusion.

2.1 First premise

Christiano (2013) writes:

If the next generation is created by the current generation, guided by the current generation's values, then the properties of the next generation will be disproportionately affected by those who care most strongly about the future.

Presumably, Christiano makes the implicit assumption that the next generation is created by the current generation and guided by the current generation's values. Thus, the first premise posits that those who care most strongly about the future (henceforth, 'longtermists') are likely to have a relatively higher level of influence over the future than those who do not (henceforth, 'shorttermists').[1] Although I challenge this premise in Section 7 by offering reasons for thinking that shorttermists will have higher influence over the future than longtermists, I grant it until then.

2.2 Second premise

The second premise of Christiano's (2013) argument posits that, on the whole, the values of these longtermists[2] are "only modestly [...] worse than [Christiano's] own values (as judged by [Christiano's] values)".[3] I challenge this premise in Section 5 by pointing out that longtermists can have fanatical values that deviate far from what Christiano would regard as acceptable, and that longtermists who do roughly share his values (henceforth, 'aligned longtermists') may be too few relative to the population size (and relative to the number of fanatics) for them to have a high level of influence over the future. In Section 6, I argue that even if we consider the influence of a group to be more than a matter of how many adherents that group has, it is not clear that aligned longtermists will have much influence relative to fanatics.

2.3 Third premise and conclusion

The third (and final) premise of Christiano's (2013) argument posits that if 1) longtermists disproportionately influence the future and 2) longtermists share Christiano’s values, then 3) the future will be good, from Christiano’s perspective.

Taken together, Christiano's three premises jointly entail the conclusion that the future will likely be good, from Christiano's perspective. In this paper, I challenge all three premises. I challenge the second premise in Section 5 and Section 6, the first premise in Section 7 and the third premise in Section 8. The conclusion I reach is that we should be deeply uncertain about whether the future will be good.

2.4 Simplifying assumptions

It will be helpful to think of a group's level of influence at time as the product of two factors: the number of people in that group at time and the level of influence of the average person in that group at time . Until Section 6, I make the simplifying assumption that each person in the population has the same level of influence. This is compatible with the deployment of AGI in so far as AGI reflects a mixture of everyone's values, assigning equal weight to the values of each person.

Moreover, until Section 7, barring a footnote in Section 5, I rule out the possibility of a value lock-in.[4] There are at least two reasons why this is not an entirely unreasonable assumption to make, at least during the timeframes I am considering. The first is that locking in values may not be feasible within these timeframes, perhaps because it takes a long time to develop AGI that is powerful enough to allow for value lock-in. The second is that, even if locking in values is feasible within these timeframes, people may choose not to do so (I explain why in Section 7).

Under these simplifying assumptions, a group has a high level of influence over the future if and only if it is highly represented in the population over a long period of time, and aligned longtermists can only be highly represented in the population over a long period of time if they succeed in propagating their values in such a way that the proportion of aligned longtermists increases to a sizeable share of the population and maintains this share over a long period of time. In writing what I quoted in Section 2.1, Christiano (2013) seems to think that this is indeed what will happen.

3. Model

One way to model the propagation of values over time, i.e. from one generation, or timestep,[5] to the next, is with the replicator dynamics. At the core of the replicator dynamics is the replicator equation. The continuous form of the replicator equation is a differential equation used in evolutionary game theory to describe the change in the frequency of strategies within a population over time. It can be applied in the current context to describe the change in proportions of groups over time. According to the replicator equation, the proportion of a group at time is a function of the proportions of all groups at time and the propagation rate of each group at time . In particular, the proportion of a group increases if the propagation rate of that group is higher than the average propagation rate of the population, decreases if the propagation rate of that group is lower than the average propagation rate of the population, and is unaltered if the propagation rate of that group is equal to the average propagation rate of the population.

Formally, where denotes the proportion of agents of group in the population at time , denotes the propagation rate of agents of group at time , and denotes the average propagation rate of the population, the continuous replicator equation is given by:

The term measures the propagation rate of group compared to the average propagation rate of the population.

4. Assuming that longtermists are all aligned

If we assume that the only groups are aligned longtermists on the one hand and shorttermists on the other, that their initial proportions in the population are each higher than zero (and sum to 1), and that the propagation rate of aligned longtermists, at each timestep, is strictly higher than that of shorttermists,[6] then, in the limit as , the proportion of aligned longtermists will approach 1 and the proportion of shorttermists will approach 0. This is proven in Appendix A.

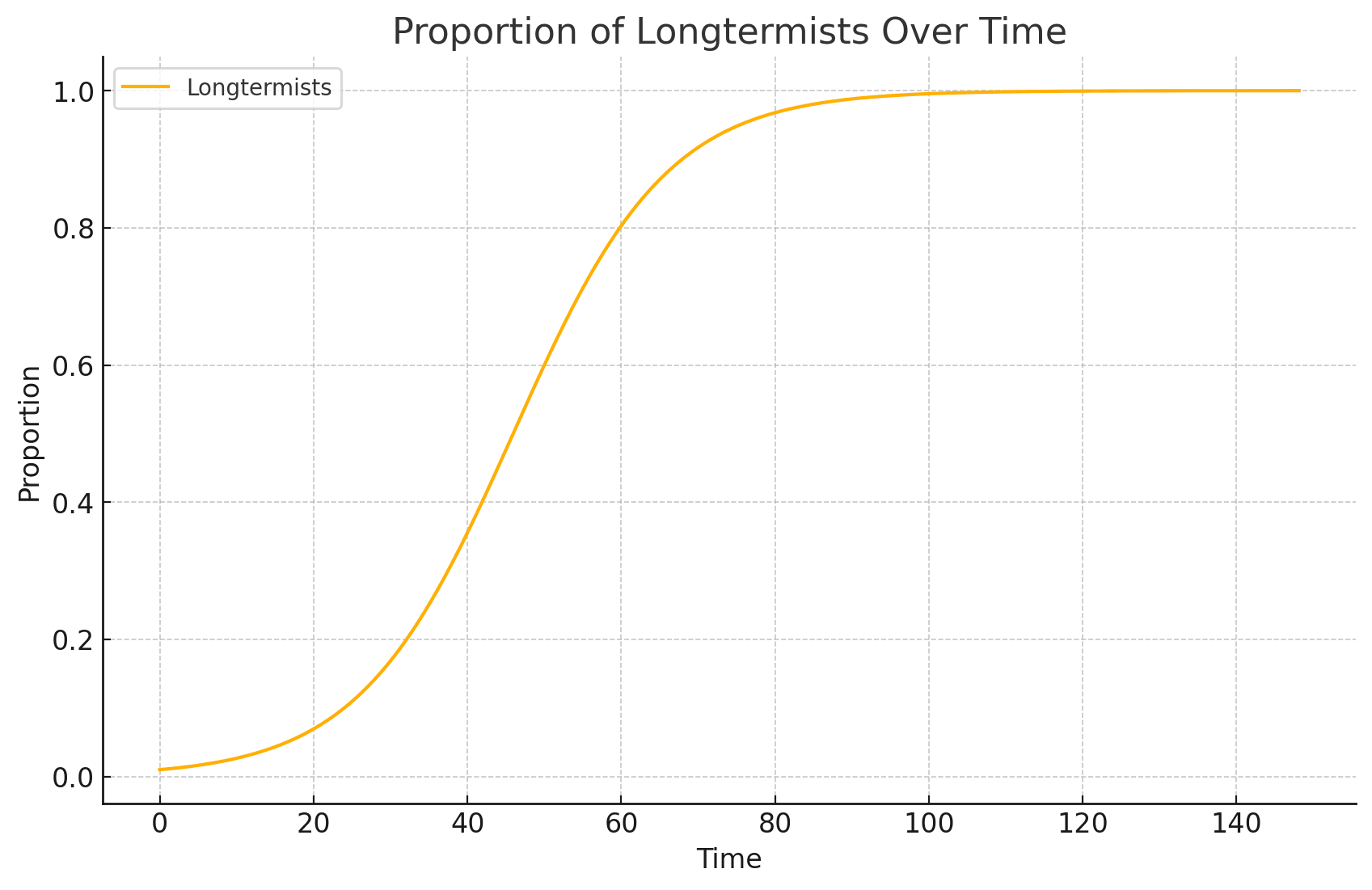

The graph in Figure 1 represents the change in the proportion of aligned longtermists in a population over time, where aligned longtermists initially comprise 1% of the population (and shorttermists 99%) and have a 10% higher propagation rate than shorttermists, meaning that, from one timestep to the next, the absolute growth factor of aligned longtermists is 10% higher than that of shorttermists, whatever the absolute growth factor of shorttermists. I have left the unit of time (on the x-axis) unspecified to allow for different specifications based on what seems most reasonable. If we expect aligned longtermists to have a 10% higher propagation rate than shorttermists over the course of one year, then time is measured in years; if we more modestly expect aligned longtermists to have a 10% higher propagation rate than shorttermists over the course of one decade, then time is measured in decades. Under the former specification, aligned longtermists constitute 5% of the population within 7 years; under the latter (more modest) specification, they constitute 5% within 7 decades.

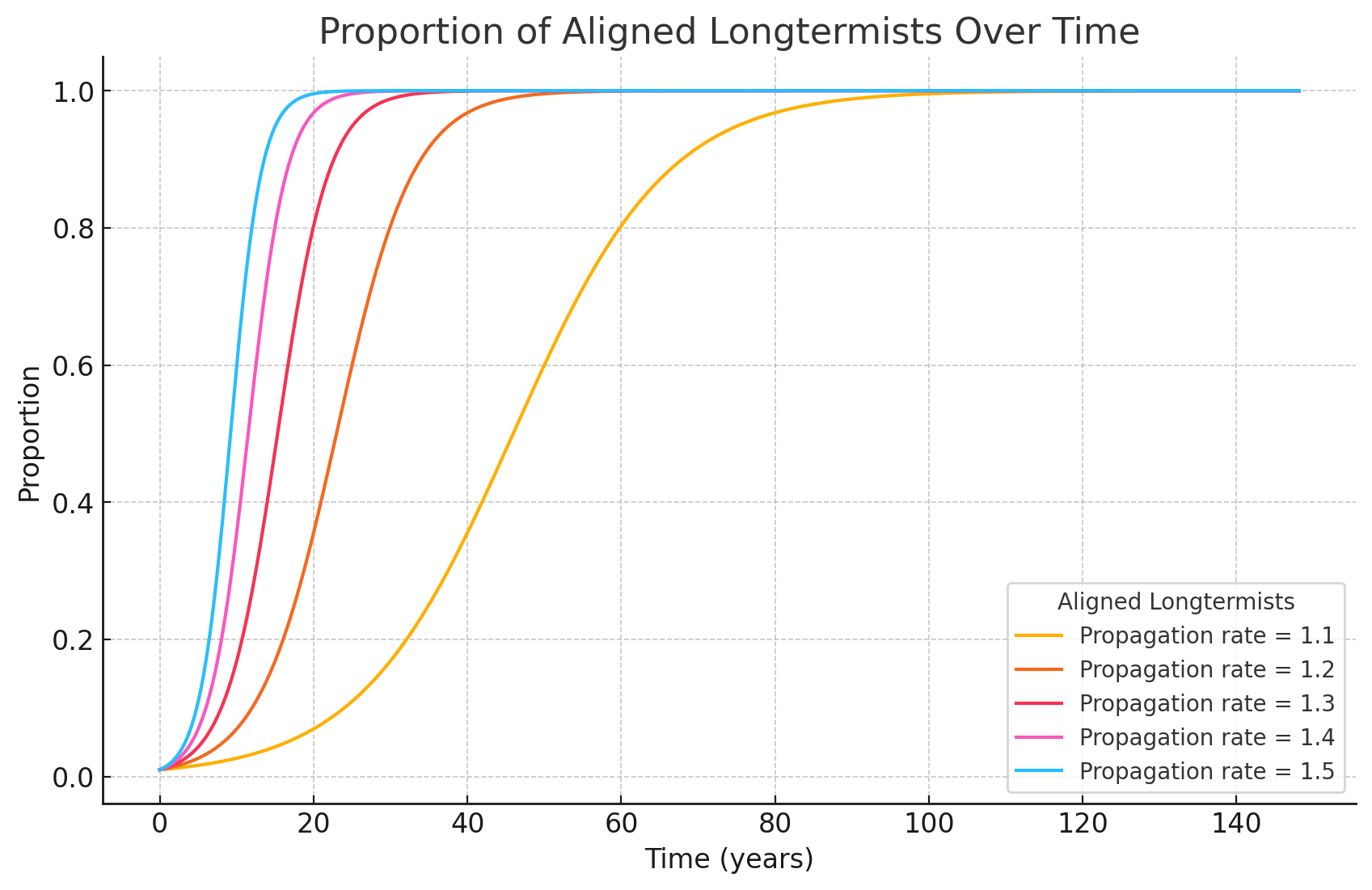

The graph in Figure 2 is like that in Figure 1 except that it displays the curves for various aligned longtermist propagation rates relative to the propagation rate of shorttermists, which is fixed at 1, and time is measured in years. Which curve is most accurate depends on which propagation rate is most plausible. If it is plausible that aligned longtermists have a 50% higher propagation rate than shorttermists over the course of a year, then, within 5 years, aligned longtermists will constitute 10% of the population, and, within 10 years, they will constitute 60% of the population.

Were the assumptions of this model accurate, the future would be largely in the hands of aligned longtermists under a wide range of plausible relative propagation rates. However, in the following sections, I cast doubt on some of these assumptions.

5. Fanatical values

So far, I have assumed that aligned longtermists and shorttermists are the only groups in the population. However, there are also people who have fanatical values that deviate far from Christiano's and yet care strongly about the future, and so are longtermists by the definition employed in this paper. This contradicts the second premise of Christiano's argument. For example, there are religious fanatics (e.g. Christian fundamentalists and radical Islamists), political fanatics (e.g. Nazis and Maoists), ultra-nationalists, and ethnic supremacists, all of whom have a vision of how the world should be and are presumably likely to take opportunities to shape the world according to their values. Since their values differ greatly from Christiano's, a future shaped by one of these fanatical groups would not be a good one, from Christiano's perspective.

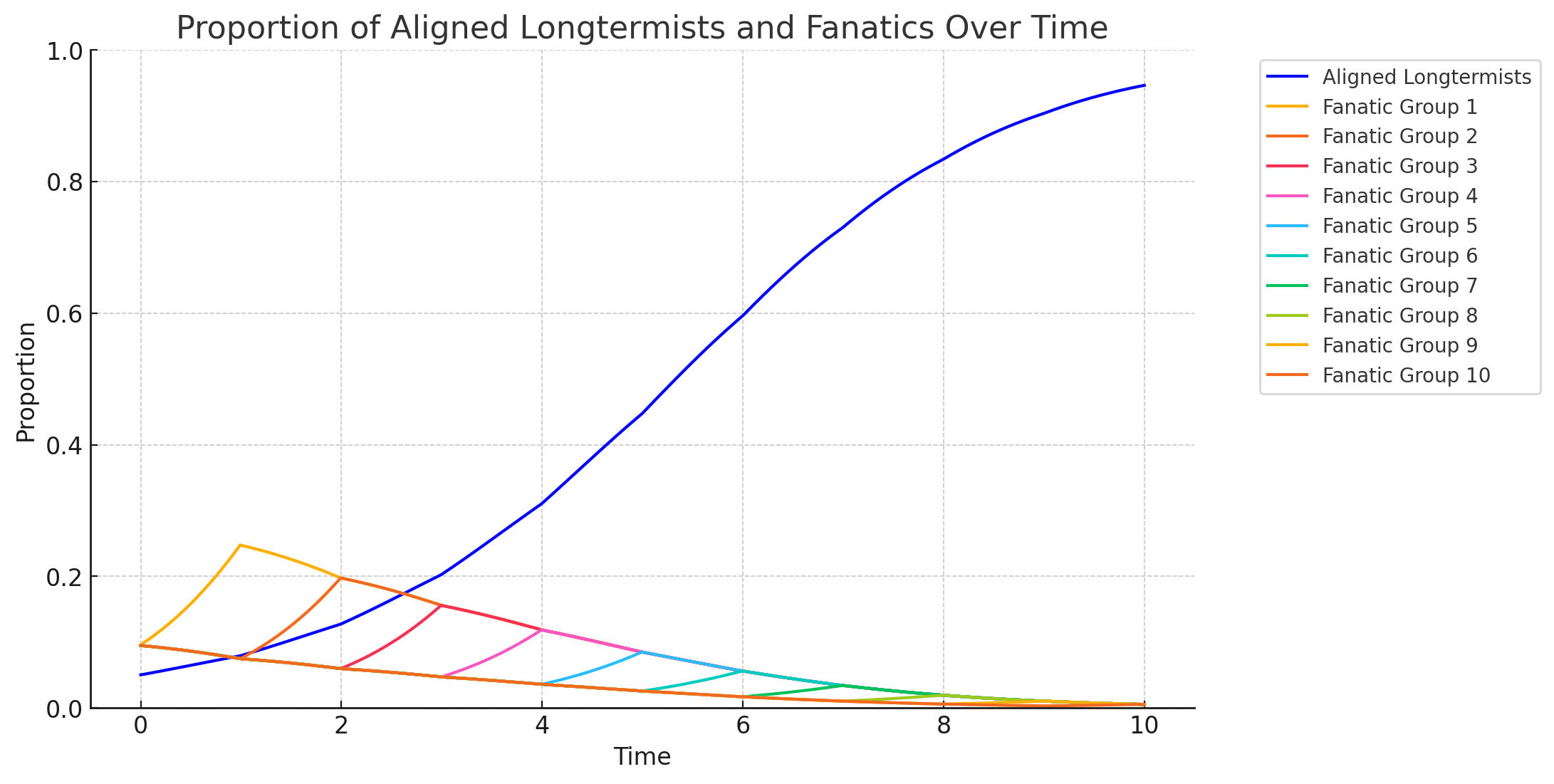

Given that fanatics exist in the population and have influence over the world, the model should not omit them. There are many different fanatical groups. Presumably, some have a higher propagation rate than aligned longtermists. The graph in Figure 3 represents the change in the proportions of aligned longtermists and one group of fanatics over time, where aligned longtermists have a constant propagation rate of 1.5 and initially comprise 1% of the population, the group of fanatics have a constant propagation rate of 1.8 (which is 20% higher than that of aligned longtermists) and initially comprise 0.2% of the population, and the rest of the population is comprised of shorttermists who have a propagation rate of 1. Under these parameter settings, the proportion of aligned longtermists initially increases (until it reaches just over 20%) but subsequently decreases. Meanwhile, the proportion of fanatics increases monotonically.

Admittedly, it is rather implausible to suppose that a fanatical group will have a persistently higher propagation rate than aligned longtermists, but it is also implausible to suppose that aligned longtermists will have a persistently higher propagation rate than all fanatical groups. The important question is whether aligned longtermists will have a higher propagation rate, over the long run, than any fanatical group.[7]

Christiano would presumably respond in the affirmative. I will offer two arguments in Christiano's defence, criticising each in turn. The first argument relates to the natural appeal of aligned longtermism over fanatical ideologies. It is that the idea that we should think carefully about how to do the most good and that we should be impartial with respect to beings across space and time is naturally appealing. In contrast, fanatical ideologies, especially in their more obvious forms, are difficult for many people to embrace.

However, whilst this may be true in times of peace, stability and prosperity, it is certainly not always true. Human history is replete with examples of fanatical ideologies propagating rapidly: Christian fundamentalism in the medieval and early modern periods, marked by the Crusades and the Inquisitions; Nazism in the 1930s and 1940s, marked by the Holocaust and World War II; Maoism in the 1960s and 1970s, marked by the Cultural Revolution. Fanatical groups appear to be effective at rapidly increasing their share of the population in environments where fear, uncertainty, and a need for strong group identity are prevalent. They often present a simple, clear, and emotionally compelling ideology that can be easily understood and propagated, especially in times of crisis, and they often foster strong in-group solidarity and commitment, resulting in more effective recruitment and retention strategies. They also frequently use fear and urgency as tools to mobilise people quickly, and tap into deep emotional and existential needs, such as the desire for identity, purpose, or belonging, making them particularly effective at attracting individuals who feel alienated or disenfranchised.

The second argument in defence of Christiano relates to the technological advantage of aligned longtermists over fanatics. It is that aligned longtermists are, generally speaking, closer to the forefront of technological innovation than fanatics, and so they may be more likely to effectively use technology, including AI, to propagate their values.

However, whilst aligned longtermists may currently have a technological advantage over fanatics, it is unclear whether this will continue for much longer. Existing fanatical groups may quickly adopt and master the latest technology, or new fanatical groups may emerge within the technological vanguard. Moreover, fanatics are less likely than aligned longtermists to hesitate to use technology in radical ways to propagate their values.[8] As Marimaa (2011) puts it:

[T]he fanatic tries to smother the plurality of opinions by any means so that his/her "truth" might prevail. If they do not succeed with verbal methods then violence and killing is used.

It is unclear whether aligned longtermists have (and will continue to have) a propagation rate that is higher, over the long run, than other longtermists, and any prediction either way will be shrouded in uncertainty. Moreover, this uncertainty runs deep: we lack a principled way of selecting a probability distribution over the relative propagation rates of different groups at each timestep, and our uncertainty is more severe at later timesteps, due to distributional shift, when social dynamics will likely differ drastically. Therefore, we should not be confident that aligned longtermists will disproportionately influence the future, and nor, therefore, should we be confident that the future will be good.[9]

6. Different levels of influence

Until now, I have made the simplifying assumption that the average person in each group has the same level of influence. As such, I have assumed that the relative influence of a group is equivalent to that group's relative number of adherents. However, in this section, I drop this assumption and consider the relative influence of different groups.[10] In doing so, I present Christiano with an opportunity to resist the result represented by the graph in Figure 3. However, at the same time, I expose Christiano to a further line of critique.

To resist the result represented by the graph in Figure 3, Christiano can argue that, even if fanatics become highly represented in the population, they are unlikely to wield as much influence as aligned longtermists. One reason in favour of this view is that aligned longtermists have good epistemics and so are more likely to achieve their goals,[11] which, in essence, is equivalent to having a high level of influence. Another reason is that aligned longtermists are likely to be more willing than fanatics to compromise and cooperate with others, and are therefore likely to have more influence. However, there are reasons for thinking that fanatics will wield more influence than aligned longtermists. For example, they are more likely to seize power ruthlessly, to violate side-constraints, and to ignore and extinguish dissenting voices. As such, they can represent a huge threat to the future without having a large following. Such threats are discussed in further detail by Stephen Clare (2024).

Again, the conclusion to be drawn from this is not that we should expect fanatics to have a higher level of influence over the future than aligned longtermists, but that we should not be confident that aligned longtermists will be the ones with disproportionate influence over the future. Moreover, even if aligned longtermists end up having a far higher level of influence over the future than fanatics, the prospect of fanatics having any non-negligible level of influence over the future should concern us and weaken our confidence that the future will be good, in so far as we reject their values.

Aligned longtermists versus shorttermists

There is another reason why we should be sceptical that the future will be good. It is that even if we can safely ignore the possibility of fanatics influencing the future in negative ways and assume that the only groups are aligned longtermists and shorttermists, we should not even be confident that aligned longtermists will have a higher level of influence over the future than shorttermists.

Although Christiano (2013) acknowledges that the future is uncertain, he claims that we should be confident that the future will be disproportionately influenced by longtermists rather than shorttermists, and that this "seems like one of the most solid features of an uncertain future". He also claims that ''this picture is reasonably robust", by which he presumably means 'robust under selection effects'. Selection effects refer to the idea that certain traits, behaviors, strategies or features are more likely to be found in future systems because they contribute to the survival, reproduction, or dominance of those systems. For instance, in biological systems, traits that improve survival and reproduction tend to persist over time.[12] In the case at hand, the feature that Christiano argues is robust under selection effects is the future being disproportionately shaped by longtermists rather than shorttermists.[13] Christiano (2013) offers the following argument by way of defence:

What natural selection selects for is patience. In a thousand years, given efficient natural selection, the most influential people will be those who today cared what happens in a thousand years. Preferences about what happens to me (at least for a narrow conception of personal identity) will eventually die off, dominated by preferences about what society looks like on the longest timescales.

However, unlike the feature of biological systems developing traits that improve their survival and reproduction, the feature of longtermists having disproportionate influence over the future compared to shorttermists is not robust under selection effects. To offer just one counterpoint that Christiano seems to have neglected, aligned longtermists have stronger reasons than shorttermists not to take any radical action to influence the future.[14] Firstly, aligned longtermists are more scope-sensitive. Secondly, they are more aware of their empirical uncertainty regarding the consequences of taking radical action, e.g. they are aware of the existential risks associated with developing AGI. Thirdly, they are more aware of their moral uncertainty --- they are more aware of their ignorance regarding which values they would endorse upon reflection (i.e. their idealised values). All three of these are reasons why aligned longtermists are likely to be more hesitant to do anything that might have huge downside risks, which makes them more hesitant to take radical action to influence the future.

Christiano might accept these points but respond by arguing that aligned longtermists are still more likely than shorttermists to take radical action to influence the future because shorttermists have no desire to influence the future. However, this response seems to be mistaken. Even if a person only has short-term goals, she may still take radical actions which have huge repercussions on the future, such as shaping institutions to advance her own interests. In fact, she may be more willing to do so than someone who cares a lot about the future, especially if the person who cares a lot about the future is deeply uncertain regarding the repercussions of different potential actions. For example, Donald Trump is probably most accurately described as a shorttermist, and yet many of his decisions as US President, including his decision to withdraw the US from the Paris Climate Agreement, could have (or, at least, could have had) large long-term impacts. Therefore, the feature that the future will be disproportionately shaped by longtermists rather than shorttermists is not robust under selection effects, and so we should not be confident that the future will be disproportionately shaped by longtermists rather than shorttermists.

8. Confidence in aligned longtermists

Even if it were the case that aligned longtermists will not just disproportionately influence the future but will be the only ones to influence the future, it would still be uncertain whether the future will be good. This is because aiming for systematic long-term influence is highly intractable under deep uncertainty. One might think that such intractability can be reduced with AGI, but even if aligned longtermists have sole control over the training and deployment of AGI, there are ways this can go badly. Firstly, aligned longtermists might not succeed in aligning the values of AGI with their values (idealised or otherwise).[15] Secondly, even if they succeed in aligning the values of AGI with their values, these values may not be endorsed by aligned longtermists upon reflection.

There are other ways the future can go badly even when aligned longtermists have sole influence over the future. For example, there is the possibility of conflict with aliens, which can lead to disastrous outcomes.[16]

9. Conclusion

In this paper, I began by offering a reconstruction of Christiano's (2013) argument in premise form, whose conclusion is that the future will likely be good. I then proceeded to challenge all three of his premises on various grounds, with my central thesis being that we should not be confident that the future will be good. Whilst I have offered a model, based on the replicator equation, for forecasting trends in the relative number and influence of aligned longtermists, I have highlighted how uncertain we are regarding the current and future propagation rates of aligned longtermists and other groups.[17] Moreover, the model I have offered is highly simplified and either omits a large number of important parameters (if the population in the model is not weighted by level of influence), or it omits none but has one parameter, namely 'propagation rate', which is highly intractable to estimate (if the population in the model is weighted by level of influence). Either way, we are in a position of deep uncertainty regarding whether the future will be good. Given this, we should not simply work on mitigating extinction risks, but should try to develop more accurate ways of forecasting how good the future will be and take actions which will robustly influence the future in a positive direction, or at least robustly decrease the risk of a negative future.

I have already discussed some ways that the future might go badly. Future work should explore these further and devise interventions that can mitigate them, e.g. limiting the technological capabilities of fanatics, as well as investigate other potential sources of disvalue that I have omitted in this paper.

Acknowledgements

I completed this project during the 2024 Summer Research Fellowship at the Center on Long-Term Risk (CLR). I am thankful to everyone at CLR for welcoming me and for providing feedback and inspiration on this project. I am especially thankful to Tristan Cook for his excellent mentorship throughout my time at CLR. David Althaus helped flesh out my thoughts on fanatical groups and Anthony DiGiovanni gave me valuable feedback on this project. All mistakes and shortcomings are mine.

Appendix A

Theorem

Let:

- be the proportion of longtermists at time ,

- be the proportion of shorttermists at time ,

- be the propagation rate of longtermists at time , and

- be the propagation rate of shorttermists at time .

Assume that for all , and that . Then, in the limit as , and .

Proof

The continuous replicator equation for the proportion of longtermists is given by:

,

where is the average propagation rate of the population, given by:

.

Substituting into the replicator equation yields:

,

which simplifies to:

.

By assumption:

.

Thus, the right-hand side of the equation is strictly positive for , meaning that:

whenever . Therefore, is strictly increasing over time, provided that .

To conclude the proof, consider what happens as . Since is strictly increasing and bounded above by 1, it must converge to a limit. Let denote this limit. If , then , contradicting the assumption that has reached a stable value. Therefore, the only possible limit is .

Since , it follows that:

as

Thus, in the limit as , the proportion of longtermists tends to 1 and the proportion of shorttermists tends to 0.

Appendix B

- ^

Christiano (2013) mostly speaks of 'altruists' as opposed to 'longtermists', and 'egoists' as opposed to 'shorttermists'. However, using his original terminology would render the first premise a lot less plausible.

- ^

In articulating this second premise, Christiano talks in terms of 'longtermist values' (specifically, "humanity’s long-term interests") as opposed to 'longtermist people' (i.e. 'longtermists'). This seems more appropriate because a person can have both longtermist and shorttermist values and, if Christiano is correct with regard to the first premise of his argument, it is that person’s longtermist rather than shorttermist values which disproportionately affect the future. However, for the sake of simplicity, I shall model the situation in line with the phrasing that Christiano uses in his articulation of the first premise of his argument, i.e. where there is a rigid dichotomy between longtermists and shorttermists. This simplification should not have any significant bearing on the results.

- ^

As far as Christiano expects his argument to be compelling to readers, he presumably thinks that his argument will go through with respect to the reader's values and not just his own. Therefore, the second premise could also be formulated in terms of the reader’s values: 'On the whole, the values of these longtermists are only modestly worse than the reader’s own values (as judged by the reader’s values)'.

- ^

In so doing, my model is not rendered useless in the event that locking in values becomes a real possibility. In fact, my model helps aligned longtermists deliberate about when, if ever, they should lock in their values. This is because it informs them of the counterfactual regarding what to expect were value lock-in not to occur.

- ^

Although Christiano talks in terms of 'generations', the replicator dynamics can be interpreted more broadly as describing the evolution of a population from one timestep to the next. Therefore, at one end of the spectrum, the members of a population at the second timestep could be thought of as a whole new set of agents, distinct from those in the population at the first timestep --- this is sometimes referred to as 'biological evolution' --- at the other end of the spectrum, they could be thought of as the exact same agents albeit with potentially different values --- this is sometimes referred to as 'cultural evolution'.

- ^

Naturally, some aligned longtermists will have a higher propagation rate than others, and, similarly, some shorttermists will have a higher propagation rate than others. It may also be the case that some shorttermists will have a higher propagation rate than some longtermists. However, when I talk of the propagation rate of a group, I mean the average propagation rate of the group's adherents.

- ^

It is possible for aligned longtermists to outnumber fanatics despite aligned longtermists having a propagation rate that is always strictly lower than that of a fanatical group, even when aligned longtermists initially comprise a lower proportion of the population than each fanatical group. An example of this is represented by a graph in Figure 4 included in Appendix B. This works in Christiano's defence in so far as we expect fanatics, and not aligned longtermists, to frequently have low propagation rates, even if their propagation rates are occasionally high.

- ^

The three reasons I offer, in Section 7, for why aligned longtermists are less likely than shorttermists to take any radical action to influence the future also explain why aligned longtermists are more likely than fanatics to hesitate to use technology in radial ways to propagate their values.

- ^

In response, Christiano could argue that even if a fanatical group has a persistently higher propagation rate than aligned longtermists, aligned longtermists might be able to lock in their values before they become outnumbered by fanatics, and that, therefore, we should expect the future to be good. However, this defence seems to rely on two contentious assumptions. One, which I discuss in Section 7, is that aligned longtermists will lock in values before anyone else. The other, which I discuss in Section 8, is that the values they lock in are their values (or their idealised values) and that the future will be good as a result.

- ^

After a minor reinterpretation, the model I put forward in Section 3 can be used to explore projected trends in the proportion of aligned longtermists (and other groups) even after dropping the assumption of equal influence. Until now, I have interpreted the term 'population' as something like 'the collection of living people'. However, I will henceforth interpret the term 'population' as 'the collection of living people weighted by their level of influence, such that weight is assigned to people in proportion to their level of influence'. Note that this interpretation is general enough to capture the former interpretation. In particular, it is equivalent to the former interpretation when each person is assigned equal weight.

- ^

This point is most obvious under epistemic instrumentalism, which holds that the value of epistemic norms lies in their usefulness for achieving practical goals.

- ^

Similarly, we might expect that AI systems which are highly effective at self-preservation, resource acquisition, or strategic planning are more likely to persist and influence the future.

- ^

Others use the term 'deep parameters' instead of 'robust features'.

- ^

By 'radical action', I mean actions and interventions that are extreme, far-reaching, risky, irreversible or highly transformative. Locking in one's values is one such example.

- ^

Christiano presumably agrees with this point, which only makes it more surprising that he is confident that the future will be good.

- ^

One might object that I am applying a double standard. I argue that aligned longtermists can fail to make the future go well, from the perspective of aligned longtermists, so must I not also accept that, to the same extent, fanatics can fail to make the future go badly, from the perspective of aligned longtermists? I think there is an important asymmetry. It is that, whilst there are many ways for the future to go badly, there are not so many ways for it to go well.

- ^

We can, however, develop a reasonable estimate of the current proportion and influence of different groups in the population, for example by surveying people about their values and wealth.

Executive summary: This exploratory paper challenges Paul Christiano’s 2013 argument that the future is likely to be good by systematically critiquing its premises and introducing a population dynamics model, ultimately concluding that we are in a state of deep uncertainty about whether the future will be good—especially given the unpredictable influence of fanatics, shorttermists, and technological complexities.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.