TL;DR

I badly managed the leadership handover of a vegan uni group I founded. The mistakes I made made everything more stressful and lagged the transition. The mistakes were: Not prioritizing leader selection, sticking with unfit candidates, lacking clear communication, and being overly controlling.

The lessons I learned here made the succession of the other EA uni group I've founded much easier. The lessons were: Use diverse recruitment channels, be very transparent, don't tie your self-worth to the success of the group, trust people and let them lead instead of you.

Intro

University groups can (and sadly often do) die off, generally when the leader leaves the group without a qualified successor. I believe this is normal. Leadership transition is messy and complicated. Plus being 19-year-old volunteers with zero management experience certainly does not help. I've founded 2 student orgs in university and handed the leadership over in both. One had a butter-smooth succession and the other... well, let's just say much more messy and stressful. I did fall into many pitfalls, making my process stressful and longer. But the mistakes I made there made the second succession MUCH better. So in this post, I'll be retelling my mistakes and lessons I learned through the "bad" succession.

The post is about how not to do a bad succession instead of how to do a good one. I'll be writing something for that later on.

Context

Long story short: Founded a vegan club. Succession was the top priority. Tried to onboard volunteers but no one seemed a good fit. Finally found someone who was interested and responsible but not at all motivated. Stuck with that person and stopped looking for other candidates. Finally accepted that the person was not a good fit as well. A lot of pain, stress, and not knowing what to do. Finding someone else who might be a good fit. We hit it off well, and she started to take responsibilities. My concerns made our transition REALLY SLOW, thus I ended up doing a lot of the managerial stuff. In the end, I finally trusted her and left the group for good. The group survives and is doing great events right now.

1. "The" Mistake: Not prioritizing finding a good leader.

Probably one of the most costly mistakes I've made was not prioritizing finding a good leader from the start. Instead of prioritizing finding a good leader, I was optimizing to leave behind a group of volunteers and good systems to run the group. I thought that if each of them knew an aspect of organizing and had good decision-making and planning systems, they could run the group collectively. Well, I was wrong. Having a team and good systems is great, but we need leaders to initiate the first action, motivate and align others, and delegate the tasks. Without leaders, the group becomes disorganized, and no one thinks about whether they are 'allowed' to do something, so the motivation decreases and sadly the group dies. In the groups I've seen, the number one reason they went inactive was a lack of leadership. So if we want our group to survive, we need to find someone to take the lead after us and gradually step away while mentoring them.

The rest of this post is about these two parts: My mistakes on finding the next leader and my mistakes mentoring the person and eventually stepping away.

Thoughts on how to find a leader

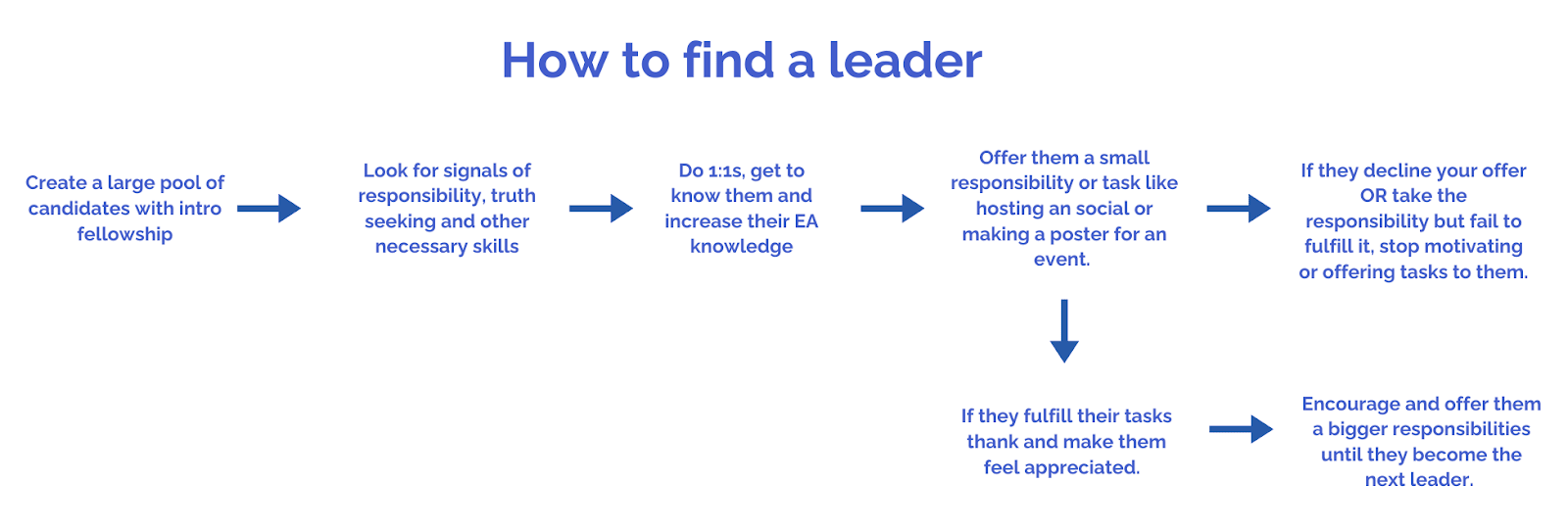

So, what makes a good leader? For me, at a bare minimum, a leader should be responsible, truth-seeking, have an interest in EA, and have good interpersonal skills. Plus, this person needs to have time and motivation to take this position. Even if the criteria above are the bare minimum, it's still VERY hard to find someone who has "all" the above. Here's an oversimplified model I've used to find someone like this:

Create a large pool of people interested in EA. Later, test their fit by offering incrementally larger responsibilities. If they successfully fulfill their responsibilities and show evidence of responsibility, interest in EA, truth-seeking, and good interpersonal skills, with time they can be the next leader.

Part A: Mistakes in finding the next leader

2. Thinking that every good volunteer would make a good leader

When I realized I needed a leader, I wasn't that worried. Due to the onboarding efforts, there were ~10 motivated people taking responsibilities, and I thought at least one of them could take the lead. I was wrong.

Just because a volunteer is responsible, truth-seeking, and motivated does not mean they are a good fit for leadership. First, they may just not want to take the leadership position. They may have other priorities and just want to help in a non-leader role. Moreover, even if they want to take the lead, the position requires much more than the qualities above. They need to have more interest, be ready to give much more time commitment, and own the group emotionally. Due to these additional qualities, not every good volunteer makes a good leader. I've missed this distinction and ended up with a bunch of volunteers but no one to lead them. I had to specifically search and onboard leader candidates again.

Lesson:

- Not every volunteer with the right qualities makes a leader. Search specifically for leaders.

3. Not letting go of your leader candidate.

There was one person who could have been the next president after me. She was responsible, proactive, and motivated. This made me believe that I could leave the group to her. I was wrong. She was extremely anxious about whether she could do her schoolwork alongside the group. She didn't want to be visible at all. She did take many responsibilities, but something was not right. I tried to encourage her by doing 1:1s and offering all kinds of support. But her interest in veganism and the group was declining. She just simply wasn't excited or motivated enough to lead a group. After many tries from both her and my side, she left the group for good.

Looking back now, I think the reason I couldn't realize the problem was due to my desperation. I knew I didn't have anyone else I could leave the group with. My dependence blinded me to see how she was unfit for the role. I didn't want to have the anxiety of not having anyone to leave the group with. So, when I saw a signal of her lack of motivation, I'd just say: "Ahh I just need to motivate and encourage them" to feel better" even if it was the 10th time I'm trying to deeply encourage them. Not accepting reality cost me a lot of time. I should have let her go and searched for others.

Many lessons here:

- Motivation and ownership are much more important for a leader than I expected.

- Make increasing the pool of possible leader candidates a priority. Constantly seek opportunities and try different methods to recruit or increase the engagement of people.

- Don't let your emotions obscure reality. Ask yourself: What is the evidence that they are a good fit for the leadership role? What is the evidence against it?

4. Not sharing thoughts and expectations with people

Another mistake I made was not sharing my intentions or expectations with people. As I've said above, I was putting all my eggs in one basket with one person. But I didn't even share this with her. I was afraid that the responsibility would scare her off or it would come out as pushy, and I didn't want to overwhelm her.

While these concerns may be valid, they ultimately prevented me from expressing my thoughts and expectations to her. If I had been more transparent, I could have realized much sooner that she didn't want the position at all. I could have started looking for someone else much sooner. Not being communicative made me waste a lot of time training someone for a position they didn't even want in the first place.

I believe this is actually very usual. I've heard that a lot of EA group organizers leave a bomb of expectations and responsibilities to the next most engaged member without warning or training. This is just not nice in general and is bad for the group in many ways.

Of course, you shouldn't scare people with high expectations. It's possible to communicate potential roles they can take without overwhelming them. You can just go with something like: "Hey, you've made 'x, y, z' so far, and these made me think you can be a great next leader. Of course, no pressure right now, but what would you think about this?"

According to their response, you can create a roadmap together. They can first try out a couple of presidential responsibilities and later become co-president with you and slowly take more and more responsibilities. If at any point in this process they decide not to continue, that's perfectly fine! By communicating well, you didn't have unrealistic expectations of someone. Now you can carry on with someone else.

Lesson:

- Actively share your thoughts and expectations with people. It's possible to do so without being overwhelming.

Good Call: Leaving a team with the leader

Succession talk in EA groups is generally about finding a leader. I think this is correct since it’s the most important bottleneck for groups to survive. But also consider leaving a team to that leader. It could increase the survival chance and the impact of your group significantly.

First, it’s already low-cost to create a team. To find a leader with the skills above, you already need to test a lot of people by giving responsibilities. Most of these people won’t end up as the president of the group. But they still can be really helpful and take major responsibilities as board members or facilitators. So in the process of finding a leader, you’ll find many others who can help later on for that leader.

Having a team also makes it easier to find a leader as well. Both in my vegan and EA groups the person I handed the group over to was much more comfortable taking the position of leadership since both knew that they had other board members whom they can trust to run the group with. It’s already scary to take a leadership position. We can make it less so by leaving a supportive team for the next leader.

5. Not using many channels to find leader candidates

When I first started looking for leader candidates, I created a large pool of freshmen engaging with the group and later tried to find someone suitable there. Even if this is an "ok" strategy, it's not diverse enough. In the end, the person I handed the group over to wasn't a freshman. She was a friend of a vegan friend who wasn't engaged with our group. There are many other channels and demographics to reach out to; some examples: 1:1 outreach to friends, people very active in other clubs, environmental club members, or something else. I could have found my leader much sooner and easier if I diversified my outreach portfolio.

Lesson:

- Use many channels and go to different demographics to diversify your leader candidates.

Good Call: Talking to People

Even with this many mistakes, I ended up handing the group over. This was because I've realized the mistakes and course corrected. Talking to people was the easiest way for me to realize the mistakes. I'd talk about my uncertainties, get feedback, tell what worked and what did not. Either just hearing myself or getting advice from others helped me spot my mistakes and change direction. I was so surprised how I missed many obvious pitfalls.

Good Call:

- We are blind to many mistakes we are making. Talk to people to detect them.

Part B: Actually handing the group over.

After many mistakes and realizing them, I eventually found someone suitable to hand the group over. Now it's time to see the mistakes I made in the second part of the handover process: Mentoring the next leader and stepping down.

6. Still taking managerial responsibilities

Even if we were in the middle of the succession, I found myself calling for meetings, drafting plans, delegating tasks, and guiding other volunteers.

This created two problems:

- The new leader did not get used to the responsibilities above.

- I was still "the leader" in people's minds.

The succession is mostly a mental shift. It's in your, the next leader's, and other people's minds. Everyone needs to have the mental shift of:

"The old leader is gone, and the new leader has taken the position."

This is needed so that people will come to them for help or reporting instead of you. If you keep doing the managerial tasks above, the shift cannot happen. Create a list of these tasks, share it with the next leader, and help them on how they can do them. Only by this, the new leader will actually start to feel like "the actual" president. They can't if you still do their tasks for them.

Lesson:

- Stop taking managerial responsibilities. Be a mentor rather than a leader.

7. Not shutting up

I generally like to speak up and tell my ideas about something that I care about. But in the case of our uni group, talking made my succession worse. I was the person who had been there the most in the team. I recruited and mentored all the other people. This led me to have an unbalanced position in the group. When I'd propose something, it wouldn't get challenged or discussed. Because of this, what I proposed would directly become what we would do without others' contribution.

This is bad for a normal group and very bad for a group that is having a transition. When the new organizer(s) is taking charge, they need to own the group. They cannot own the group if their ideas are not implemented or even shared. When I finally stopped talking, the next leader and others actually started to give their ideas. They were much more motivated and interested in running the group. It started being "their" group rather than "mine alone".

Lesson:

- Do shut up. Stop sharing ideas, stop taking initiative. Let others talk and do so that they can own the group.

8. Being the “savior of the day”

Okay, I have found the next leader, I've shut myself up, stopped doing managerial tasks for the group. But it is not over. I need to get used to not "fix" stuff when they arise. It's a time for change, and in the times of change, a lot of stuff goes wrong.

My mistake was "saving the day" when something went wrong. People knew this and wouldn't take action since they knew that I'd solve it. This was a problem since I will be gone, and the group should be ready to handle crises without me. The best way to ensure this is by communicating clearly with the new leader about it, saying that you won't be intervening if something goes wrong.

This is easier said than done. It's tough to see and not fix a problem with something you really care. But this is necessary. Stuff can go wrong, and it's okay. The group needs to learn to exist by itself, and that may require bumps and mistakes along the way.

Lesson:

- Don't save the day if something goes wrong. Just give your advice and caution. The group should be able to handle crises without you.

Root causes of the mistakes

9. Tying my self-worth to the group

I was working so hard for the group. A lot of people knew me from my affiliation with it. I started to believe that if the group failed after me, this would be proof for myself and everyone else that I SUCK. I did one big project in university, and it failed. Hard proof that I'm incompetent, shouldn't be trusted and/or worked with. Saying this out loud is silly, but when the thoughts are not written out, you can't judge if they are rational or not.

This made everything, including the succession, harder. It made me into a perfectionist micromanager, which ended up jeopardizing my relationship with the new leader. Maybe more importantly, it really affected my mental health. I was really stressed and anxious. I've started to hate the thing that I was really passionate about. In the end, I've let go. I've accepted the possibility of failing. Even if it fails, it won't affect my self-worth.

Lesson:

- Don't tie your self-worth to the group. It's silly, bad for your health, and decreases the chances of success.

10. Not trusting people

I thought that if I left the group, the others just wouldn't make the group survive. I didn't trust them to take care of it as well as I could. This underlying belief made everything harder. Made the process very slow, worsened my relationships with others, and much more. There are several problems with this belief:

NO in fact, not only me but a lot of people have the skills to run a university group (what a surprise). Yes, they weren't as obsessive as I was, but they are still doing okay or even better. I had the wrong proxy of → to make a good uni group, you need to be obsessed with it. And after seeing the people who are taking charge were not obsessed with it, I was worried that they were not a good fit.

Secondly, me not trusting and worrying did not serve anything. I'd do my best to find people. I have to trust them so that they can try to lead. If they don't end up being a good leader, they can switch with someone else. Even if that person does not do well and maybe even the group dies. We are trying our best at the end. Sometimes we fail at things that we fought in the best way possible, and this is okay.

Conclusion

Even if it was a hard process, I don't want to be too rough on myself. In the end, the handover happened, and the group survived. Only it could have been much easier, faster, and hassle-free for me, for the current leader, and for the group. Hopefully, these mistakes can help you avoid similar bad experiences.

If you are planning or already going through a succession or just thinking about it, I'd be very eager to have a chat with you. You can contact me via email or just book a call without writing first. Have a very low bar to reach out!

Mail: gturker21@ku.edu.tr

Calendy: https://calendly.com/gturker21/guneyvirtualcoffee

Also definitely out these resources if you want to learn more:

- Succession and handover guide

- What university groups may be doing wrong in leadership succession

- Student groups should prioritize succession planning

Special thanks to Emre Kaplan, Otto Hellstörm and Oğuz Bulut Kök for their feedback to this post.

Thanks for this insightful post, for the self-reflection and transparent handling of your past mistakes! I think this could be a very valuable resource for all leaders of volunteer groups!

This was great! Will link it in the resource centre succession page :)

Valuable sharings, @guneyulasturker 🔸 ! I wonder what role - if any - funders (or mentors) can play to further incentivise/support good succession planning? (i.e. such that it is not left to chance, but by design)

Very insightful, and what I would like to add, is that I always believe a good leader is always a good follower, who values learning from others, respects diverse perspectives, adapts based on feedback and ensuring decisions are grounded in collective inputs, rather than personal authority.