[This is a cross-post from my blog, which you can find here]

The EA space is certainly a unique intersection of people from many walks of life, each with their own priorities and goals. However, an interesting contradiction arose in a recent conversation I had over dinner with friends. As I state in the conclusion, this may be either a criticism of longtermism or of vegetarian/veganism, depending on your perspective.

If you are someone who subscribes to Longtermism, (the idea that future people hold equal moral weight as compared to present people, and that we should adjust our actions to be accordingly biased to creating future growth.) Then, it seems to me that it would actually be non-optimal of you not to eat the most convenient/delicious/nutritious meal that you can find, whenever possible, and without much regard for animal welfare.

ANIMAL WELFARE VS HUMAN PREFERENCES

The argument goes like this: Whatever people may do to make future people better off, they will probably do more of it/do it better if they are more satisfied/happier. There are some studies on this (link, link, link), that suggest it might be a difference somewhere between 10-20%. Anecdotally, just take a look at the sometimes ludicrous lengths that tech companies go to please their employees. This is not altruism, it’s just good business.

So okay, great. We agree that happy people are more productive. Now let’s consider this within the domain of diet choice.

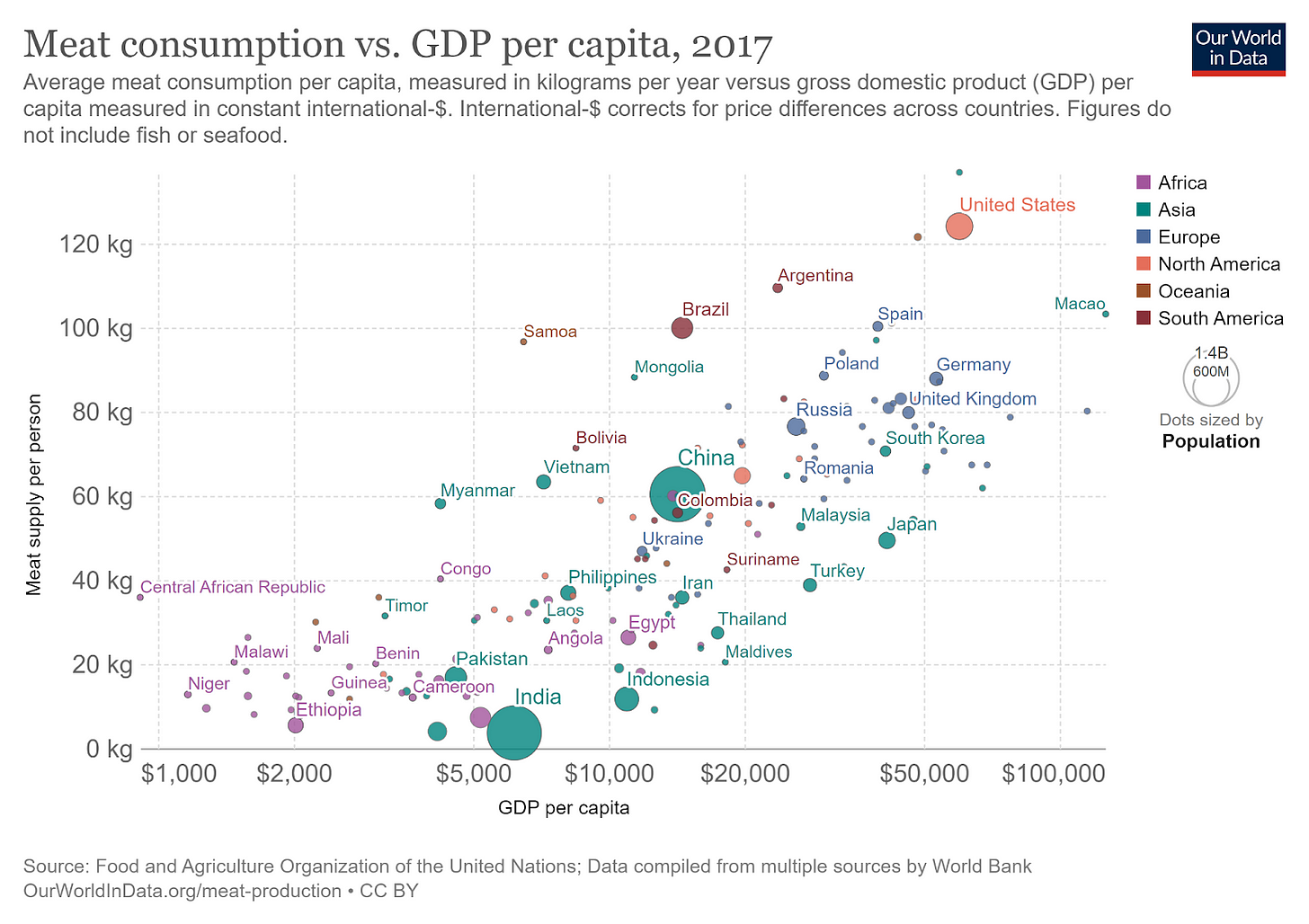

Is veganism/vegetarianism a choice that makes people happy? Maybe for some people, but usually not in a vacuum. If you truly do enjoy eating vegetarian/vegan more than a meat based diet on the basis of taste and convenience alone, more power to you. However, it seems that around the world, there is a strong revealed preference for people to eat more meat as it becomes more available. We can tell this by looking at the rate of meat consumption vs. GDP per capita.

Many vegetarians/vegans do so for religious or moral reasons, but messages that our inherent preference to eat meat is morally bad can be harmful, because they don’t actually change how a meatless diet tastes, they simply add costs like guilt and disgust in an attempt to tip the scale in people’s choices, and do not make material changes in either diet.

Okay, so we’ve now established that there is a large cost to not eating meat for those whose inherent preference it is to do so, which are a large number of people. But the key idea here, and where the Longtermist perspective becomes important, is that this cost is compounding.

Consider the following.

A researcher orders and eats a chicken sandwich for lunch everyday. He loves the chicken sandwich, it’s one of the best parts of his day, and he extracts many utils from this sandwich that allow him to exercise more willpower, and work 5% longer or harder each day. His research is completed and implemented 5% more quickly, and improves people’s lives around the world by .0001 utils on average. That’s an 800,000 util increase in well being across the world population. Some of these utils will go to other researchers, who will continue the cycle, laundering utils over and over again into untold riches and wealth for future generations.

Now consider that the 100 or so chickens that it takes to make the researchers 365 sandwiches were spared. Even if we weigh chicken utils as equal to human utils, and even if the total # of utils they experience is the same sum of 800,000, what do they do with them? A happy chicken doesn’t benefit humanity any more than a sad one, and a sad chicken doesn’t necessarily do psychic damage to humanity (although some may elect to do psychic damage to themselves on the chickens behalf). Benefits to animals are a one-time event. Therefore, the researcher’s compounding benefit will always win in the long run.

From this example, we can tell that every util that falls into human hands is worth many, many, more utils experienced by birds in the bush. Animals may very well deserve to be included in the “moral circle”, but not to the point of excluding future humans! Framing the problem in this way reveals a discrepancy in people’s sensibilities. If we ought to be so concerned about future welfare, why obsess over present suffering, especially suffering that can be written off as easily as that of animals?

Okay, so the large cost to going vegetarian/vegan is compounding while the benefits to animals are not. In my mind, that nullifies pretty much the entire animal welfare argument, but there are still other costs to eating meat that we haven't covered, and which do compound, since they are costs to humans.

COSTS TO HUMANS

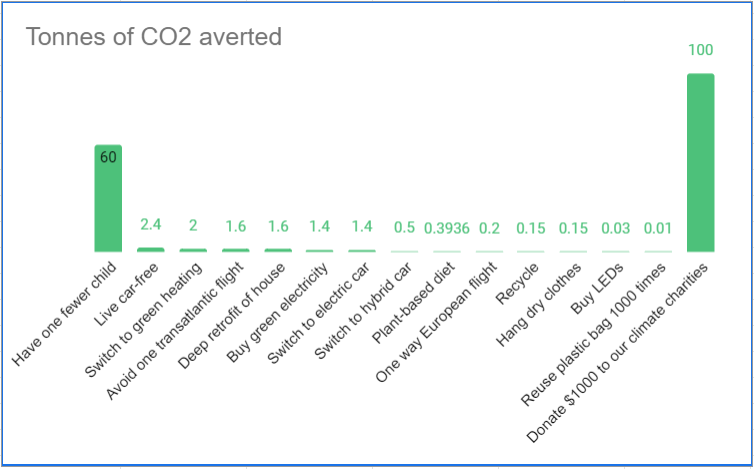

Maybe it’s not about animal suffering, but rather that vegan/vegetarianism is better for the world. Even the impact of going vegetarian/vegan on the environment is not huge when compared to the opportunity cost of being more productive and experiencing fewer inconveniences. In Will MacAsckill’s book, What We Owe The Future, he lists the stat that going vegetarian averts 0.8 tonnes of CO2 per year. At Terrapass, a carbon offset of 1000 pounds, (about .5 tonnes) is available for as low as $7.49 a month. That’s about $13.22 a month to have the same impact on the environment as going vegetarian. I think most people would agree that the cost of a Netflix subscription is worth it to continue to eat meat. If Terrapass focused on efforts that accelerated green energy technology, I’m sure they could get the price even lower. (discussed in a previous post here). Therefore, if we assume the low end of the productivity effect range I gave above (10%) and you think your work creates more than $140 a month in positive externalities, you can and should go ahead and fulfill your preference.

Graph illustrating the power of funding innovation from the Founders Pledge Climate and Lifestyle Report

This leads me to health and nutrition claims. I think that nutrition is still a rather woo-woo area of science today, and that most diet studies do not show significant health results when compared to a control diet. Therefore, I rate the health claims on either side of the meat eating divide as a wash. So let’s assume you are equally healthy eating meats vs. plants. However, this does not necessitate that you are equally as productive. Eating meat may be equally healthy as eating veggies, but it is fulfilling your preferences that makes you happy. If the researcher from the example above didn’t like the taste of chicken, it’s likely that he would not have been able to leverage that into working harder for the day.

So, to sum up, the longtermist viewpoint on whether or not you should eat meat essentially has nothing to do with animal welfare, as it is a one-time cost. When viewed on long time horizons, it is a balance between the negative externalities to the climate, and the positive externalities to work productivity which may benefit the future. Even if you elevate current animal experience to the same level as current human experience, humans are much better at carrying utility forward to future generations, while animals are just inefficient by comparison. I don’t believe that trading future humans for present animals is justifiable, and thus, if it is your preference to eat meat, I find it likely that you should continue to do so.

As always, if you think differently, please feel free to dunk on me in the comments below, maybe this is more of a criticism of longtermism than vegetarian/veganism, depending on your perspective!

FOOTNOTE:

Many vegetarians/vegans might argue that continuing to consume meat perpetuates and normalizes the way in which animals suffer in factory farming, reframing the one time benefit to animal welfare as a slippery slope, but I think that this is not a reality that is likely to persist much longer. I think that the advent of lab grown meat and breeding dumber animals will allow us to continue our consumption at a lower unit cost of animal welfare. There is some pretty compelling data that we are quite close to seeing lab grown alternatives available in supermarkets soon with some reports estimating that 35% of all meat being cultured by 2040, and that demand for plant based meats may have already peaked. However, when people do adopt cultured meats, I think that it will largely be because they are more delicious, more consistent, and cheaper, and not because of an ethical appeal. I want to eat an A-5 Wagyu steak everyday, and I think it’ll be sooner rather than later that the easiest way to produce such a luxury will be via cultured meat.

Q: Can't we just change our preferences?

I don’t really think so, and it seems even less likely that we could change our preferences without imposing costs like guilt and disgust to tip the scale. If it is your taste preference to eat meat, then it seems unlikely that you can consciously decide to prefer veggies or meat alternatives, and this is probably why veg alternatives so often try to emulate the taste of meat. I’m certainly not that in control of my preferences, but if you can will your will, more power to you.

Another example:

If your grandfather had worked one extra year in his life, how much richer might you be today? Conversely, if he had spent one of his years finding the nearest vegan restaurant, deliberating over the ethics of the impossible burger vs. the un-burger, spending more money on these hard to find ethical alternatives, watching factory farm documentaries and feeling guilty about his animal nature, and reaping fewer utils from worse-tasting food, how much poorer do you think you might be?

The second paragraph really hits on the nose how I feel, without having ever been able to put it into words - regarding both eating less animal products and recycling.