Pleasure and suffering are not conceptual opposites. Rather, pleasure and unpleasantness are conceptual opposites. Pleasure and unpleasantness are liking and disliking, or positive affect and negative affect, respectively.[1]

Imagine an experience of suffering that involved little or no effects on your attention. It's easy to ignore, along with whatever is causing it and whatever could help relieve it. We (or at least, I) would either recognize this as at most mild suffering, and perhaps not suffering at all.

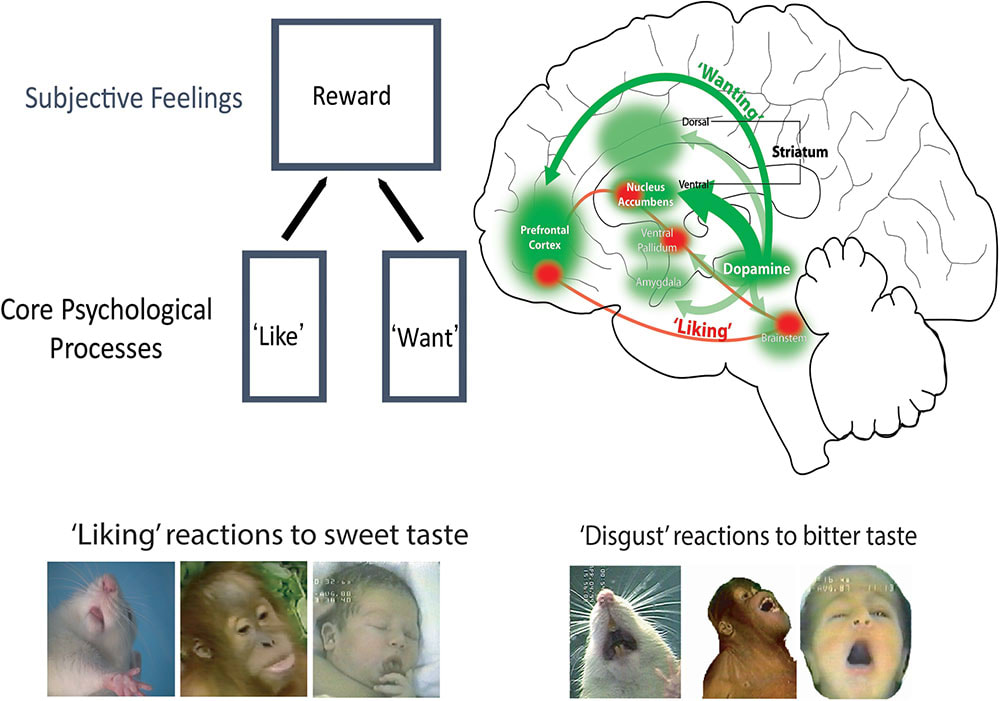

Our concept of suffering probably includes both unpleasantness and desire (or wanting), which is mediated by motivational salience (or incentive salience and aversive/threat/fearful salience), a mechanism for pulling our attention (Berridge, 2018).[2] I'd guess the apparent moral urgency we assign to intense suffering requires intense desire, and so strong effects on attention. We wouldn't mind an intensely unpleasant experience if it had no effects on our attention,[3] although it's hard for me to imagine what that would even be like. I find it easier to imagine intense pleasure without strong effects on attention.

Pleasure and unpleasantness need not involve desire, at least conceptually, and it seems pleasure at least does not require desire in humans. Desire, as motivational salience, depends on brain mechanisms in animals distinct from those for pleasure, and which can be separately manipulated (Berridge, 2018, Nguyen et al., 2021, Berridge & Dayan, 2021), including by reducing desire (incentive salience) without also reducing drug-induced euphoria (Leyton et al., 2007, Brauer & H De Wit, 1997). Berridge and Kringelbach (2015) summarize the last two studies as follows:

human subjective ratings of drug pleasure (e.g., cocaine) are not reduced by pharmacological disruption of dopamine systems, even when dopamine suppression does reduce wanting ratings (Brauer and De Wit, 1997, Leyton et al., 2007)

On the other hand, in humans and other animals, the aversive salience of physical pain may not be empirically separable from its unpleasantness (Shriver, 2014), but as far as I can tell, the issue is not settled.

- ^

Or specifically the conscious versions of these. On the possibility of unconscious liking and unconscious emotion, see Berridge & Winkielman, 2003 (pdf) and Winkielman & Berridge, 2004.

- ^

And perhaps specifically aversive desire, i.e. aversive/threat salience.

- ^

This could be true by definition, if "to mind" is taken to mean "to pay attention to" or find aversive (aversive salience), at least while experiencing the unpleasantness.

I agree you can, but that's not motivational salience. The examples you give of the watch beeping and a sudden loud sound are stimulus-driven or bottom-up salience, not motivational salience. There are apparently different underlying brain mechanisms. A summary from Kim et al., 2021:

I'd say there is some "innate" motivational salience, e.g. probably for innate drives, physical pains, innate fears and perhaps pleasant sensations, but then reinforcement (when it's working as typically) biases your systems for motivational salience and action towards things associated with those, to get more pleasure and less unpleasantness.

I'll address two things you said in opposite order.

I don't have in mind anything like a soul / homunculus. I think it's mostly a moral question, not an empirical one, to what extent we should consider the mechanisms for reinforcement to be a part of "you", and to what extent your identity persists through reinforcement. Reinforcement basically rewires your brain and changes your desires. I definitely consider your desires, as motivational salience, which have been shaped by past reinforcement, to be part of "you" now and (in my view) morally important.

From my understanding of the cognitive (neuro)science literature and their use of terms, attentional and action biases/dispositions caused by reinforcement are not necessarily "voluntary".

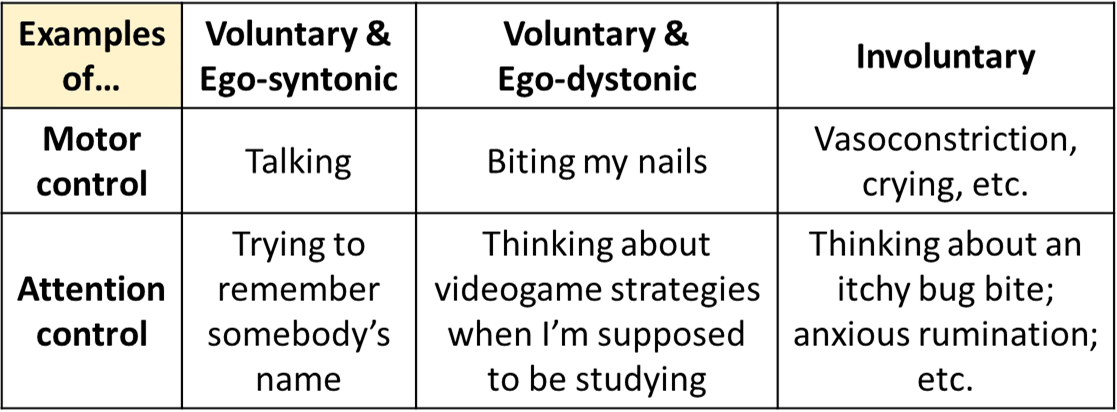

I think they use "voluntary", "endogenous", "top-down", "task-driven/directed" and "goal-driven/directed" (roughly) interchangeably for a type of attentional mechanism. For example, you have a specific task in mind, and then things related to that task become salient and your actions are biased towards actions that support that task. This is what focusing/concentration is. But then other motivationally salient stimuli (pain, hunger, your phone, an attractive person) and intense stimuli or changes in background stimuli (a beeping watch, a sudden loud noise) can get in the way.

My impression is that there is indeed a distinct mechanism describable as voluntary/endogenous/top-down attention, which lets you focus and block irrelevant but otherwise motivationally salient stimuli. It might also recruit motivational salience towards relevant stimuli. It's an executive function. And I'm inclined to reserve the term "voluntary" for executive functions.

In this way, we can say:

In both cases, reinforcement for motivational salience is partly the reason for the behaviour. But they seem less voluntary than when executive/top-down control works better.

Motivational salience can also be manipulated in experiments to lead to dissociation with remembered, predicted and actual reward (Baumgartner et al., 2021):