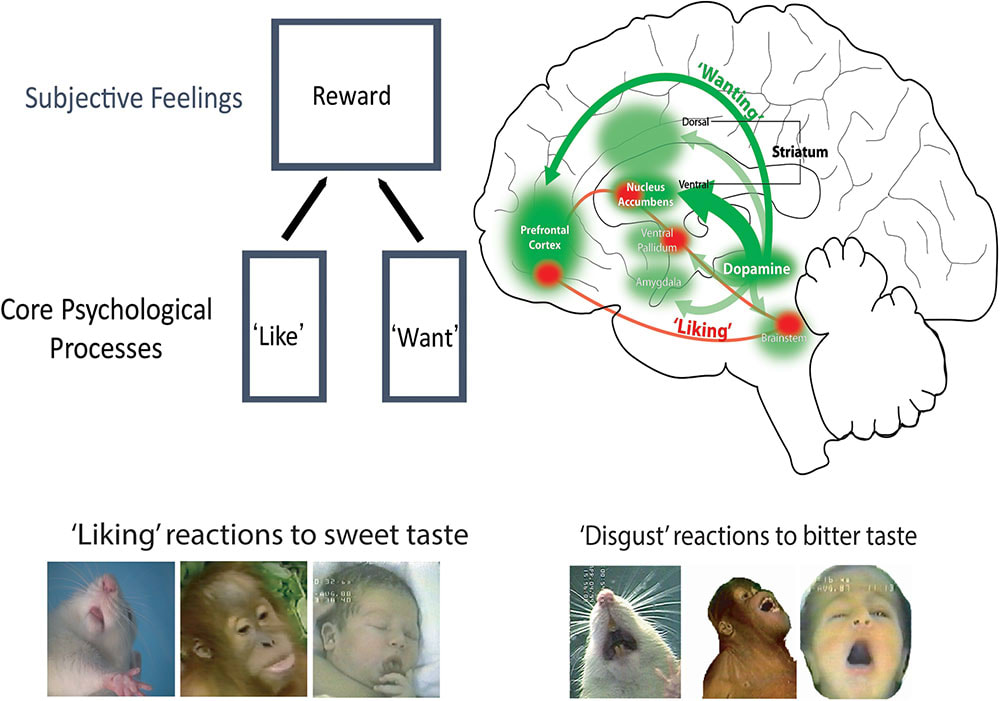

Pleasure and suffering are not conceptual opposites. Rather, pleasure and unpleasantness are conceptual opposites. Pleasure and unpleasantness are liking and disliking, or positive affect and negative affect, respectively.[1]

Imagine an experience of suffering that involved little or no effects on your attention. It's easy to ignore, along with whatever is causing it and whatever could help relieve it. We (or at least, I) would either recognize this as at most mild suffering, and perhaps not suffering at all.

Our concept of suffering probably includes both unpleasantness and desire (or wanting), which is mediated by motivational salience (or incentive salience and aversive/threat/fearful salience), a mechanism for pulling our attention (Berridge, 2018).[2] I'd guess the apparent moral urgency we assign to intense suffering requires intense desire, and so strong effects on attention. We wouldn't mind an intensely unpleasant experience if it had no effects on our attention,[3] although it's hard for me to imagine what that would even be like. I find it easier to imagine intense pleasure without strong effects on attention.

Pleasure and unpleasantness need not involve desire, at least conceptually, and it seems pleasure at least does not require desire in humans. Desire, as motivational salience, depends on brain mechanisms in animals distinct from those for pleasure, and which can be separately manipulated (Berridge, 2018, Nguyen et al., 2021, Berridge & Dayan, 2021), including by reducing desire (incentive salience) without also reducing drug-induced euphoria (Leyton et al., 2007, Brauer & H De Wit, 1997). Berridge and Kringelbach (2015) summarize the last two studies as follows:

human subjective ratings of drug pleasure (e.g., cocaine) are not reduced by pharmacological disruption of dopamine systems, even when dopamine suppression does reduce wanting ratings (Brauer and De Wit, 1997, Leyton et al., 2007)

On the other hand, in humans and other animals, the aversive salience of physical pain may not be empirically separable from its unpleasantness (Shriver, 2014), but as far as I can tell, the issue is not settled.

- ^

Or specifically the conscious versions of these. On the possibility of unconscious liking and unconscious emotion, see Berridge & Winkielman, 2003 (pdf) and Winkielman & Berridge, 2004.

- ^

And perhaps specifically aversive desire, i.e. aversive/threat salience.

- ^

This could be true by definition, if "to mind" is taken to mean "to pay attention to" or find aversive (aversive salience), at least while experiencing the unpleasantness.

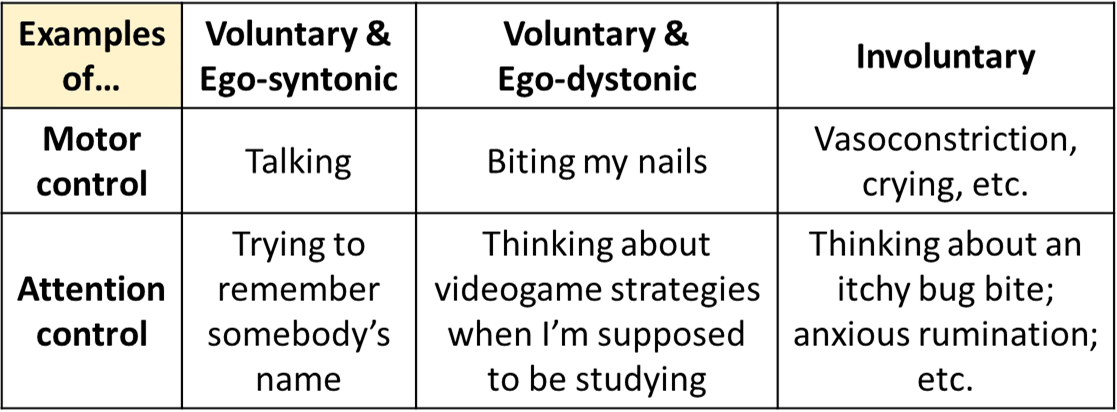

I'm pretty sympathetic to suffering ≈ displeasure + involuntary attention to the displeasure, or something similar.

I think wanting, or at least the relevant kind here, just is involuntary attention effects, specifically motivational salience. Or, at least, motivational salience is a huge part of what it is. This is how Berridge often uses the terms.[1] Maybe a conscious 'want' is just when the effects on our attention are noticeable to us, e.g. captured by our model of our own attention (attention schema), or somehow make it into the global workspace. You can feel the pull of your attention, or resistance against your voluntary attention control. Maybe it also feels different from just strong sensory stimuli (bottom-up, stimulus-driven attention).

Where I might disagree with "involuntary attention to the displeasure" is that the attention effects could sometimes be to force your attention away from an unpleasant thought, rather than to focus on it. Unpleasant signals reinforce and bias attention towards actions and things that could relieve the unpleasatness, and/or disrupt your focus so that you will find something to relieve it. Sometimes the thing that works could just be forcing your attention away from the thing that seems unpleasant, and your attention will be biased to not think about unpleasant things. Other times, you can't ignore it well enough, so you your attention will force you towards addressing it. Maybe there's some inherent bias towards focusing on the unpleasant thing.

But maybe suffering just is the kind of thing that can't be ignored this way. Would we consider an unpleasant thought that's easily ignored to be suffering?

Berridge and Robinson (2016) distinguish different kinds of wanting/desires, and equate one kind with motivational (incentive) salience: