TLDR: RP's best interventions barely qualify as Health Systems Strengthening - they focus directly on the Health worker and their implementation. Not only these, but almost all HSS interventions are measureable and should be measured! Plus some light disagreements with RP.

First a huge thanks to @Open Philanthropy and @Rethink Priorities for this report - I’m not sure any serious attempt at a cost-effectiveness analysis of Health Systems Strengthening (HSS) interventions has been done before - and they’ve done a great job. I won’t spend much time affirming all the good stuff in the report (please read at least the summary before reading this) rather I’ll double down on things I think are important or that I disagree with.

HSS is not neglected

“Health Systems Strengthening” has been a loud clarion call in the public health world for over 30 years now. There can be an almost religious fervor that the only way to make sustainable, permanent improvements in health outcomes is to improve the health system from the top down. We often hear the classic arguments that we should not put “band aids” on problems by funding vertical programs like mosquito nets and deworming, rather we should fix the “root” of the problem at the heart of the system itself.

Over the last 20 years, somewhere in the range of 100 Billion dollars might have been spent under the broader bucket of HSS[1] - hardly a neglected area. Despite this general non-neglectedness, I strongly agree with RP though that are likely to be interventions within the broader HSS bucket, which are relatively neglected and very cost-effective.

RP’s best Interventions are barely HSS and focus on Health Workers

Interventions RP found most promising (IMCI, quality improvement, CHWs) are right on the edge of “Health Systems Strengthening”. They are direct interventions that improve the number, or quality of frontline health workers. A health economics professor told me yesterday that they wouldn't consider RP's top interventions of IMCI, CHW expansion and community scorecards to qualify as HSS. It's also interesting and not noted in the report that these interventions are similar to what @CE orgs like Ansh (Close support supervision) or AMI (Med Supply chains) or @Lafiya Nigeria (CHW expansion) are already doing.

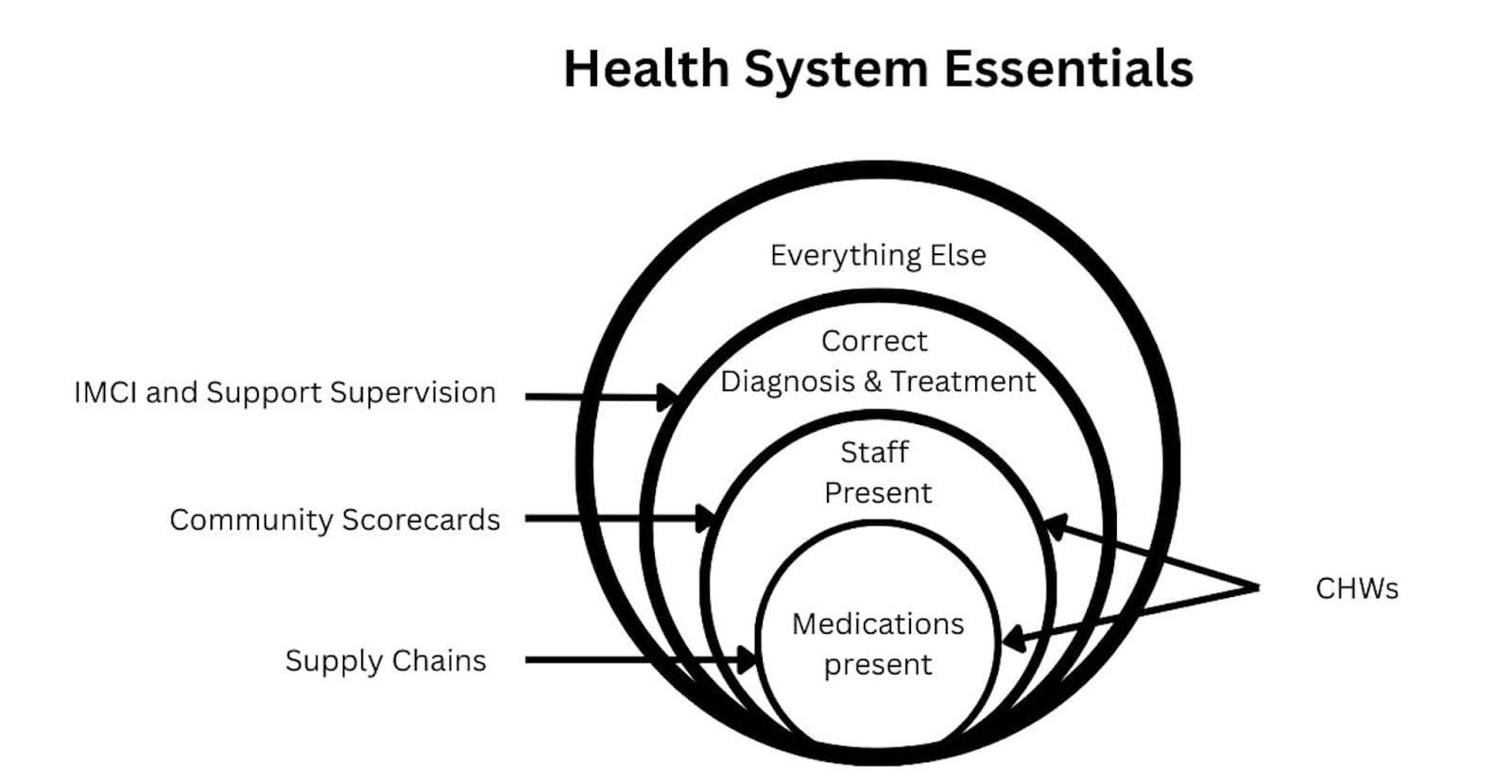

Improving the fundamental output unit of the health system - a health worker treating patients makes intuitive sense. If Health workers (CHWs) are at a facility (Scorecards) implement evidence based treatment guidelines (IMCI) and are supervised to follow those guidelines then patients will consistently receive high quality treatment and less people will die. Below I’ve cooked up a model for the essentials of a health system, which despite being painfully basic can help make sense of why these interventions might work better than the higher level ones RP considered potentially less impactful.

Too often Health Systems Strengthening focus on interventions one or more steps removed from the fundamentals, the core problem. They focus on largely useless but nice-sounding Interventions like “improving funding structures”, "high level governance", and health worker trainings that don’t solve the core problems in Low income countries. If there are no health workers or medications at a health facility then any other interventions are a waste of time and resources until those fundamental problems are fixed.

Cost-Effectiveness of HSS interventions can and should be measured

The RP recommended interventions are all measurable and indeed measured. I disagree though that most HSS interventions are too hard to measure. I don’t understand this argument from the article “Moreover, many studies do not evaluate HSS interventions comprehensively, but only focus on a few narrow outcomes. Thus, we expect that narrow, outcomes-focused studies would tend to underestimate the overall effects of an intervention.”

Yes we should look for a narrow outcome. There is usually one primary outcome in health interventions, which is healthier, happier people (measured in DALYs/WELLBYs). We often have to estimate this effect through a proxy of quality/quantity of care as mortality/morbidity is hard to measure directly. So yes the outcome is narrow. A HSS intervention might be complex, but the outcome measure should be narrow. I don’t understand how a “narrow, outcome focused study would tend to underestimate the overall effects of an intervention”

Most Health Systems interventions can be measured by RCTs. Governance, financing, and supply chain interventions can be randomised at state or district level, while service delivery and workforce interventions can be randomised at facility level[2]. For all of these, treatment quantity and quality can be used as an outcome measure - often quite straightforward in government systems with decent information systems. I challenge you to give me the intervention and I’ll give you a plausible RCT[3].

In my eyes the bigger issue is that many HSS advocates believe that interventions don’t need to be tested because HSS interventions are by nature better than vertical ones. Or sometimes they don’t have a background in RCTs or quantitative analysis so are skeptical of these methods. Also the kind of people who are drawn to HSS are people are more interested in complex systems than numbers. None of your 5 named experts seem to have a serious background in quantitative analysis. I think there are great HSS interventions and vertical ones - lets continue tomeasure them and see.

Context matters - Country >>> Intervention

RP looks at countries where health systems and outcomes have greatly improved, and conclude correctly that “large share of health improvements in positive-outlier countries were likely driven by non-health system factors (e.g., economic growth, political stabilization, improved education”. I just want to emphasize a similar point that particularly with complex HSS interventions, many systemic factors to line up for the intervention to work. We can distribute mosquito nets successfully even in fairly dysfunctional countries, but if we want to introduce a complex health insurance system, the country should be in a great state before we even try.

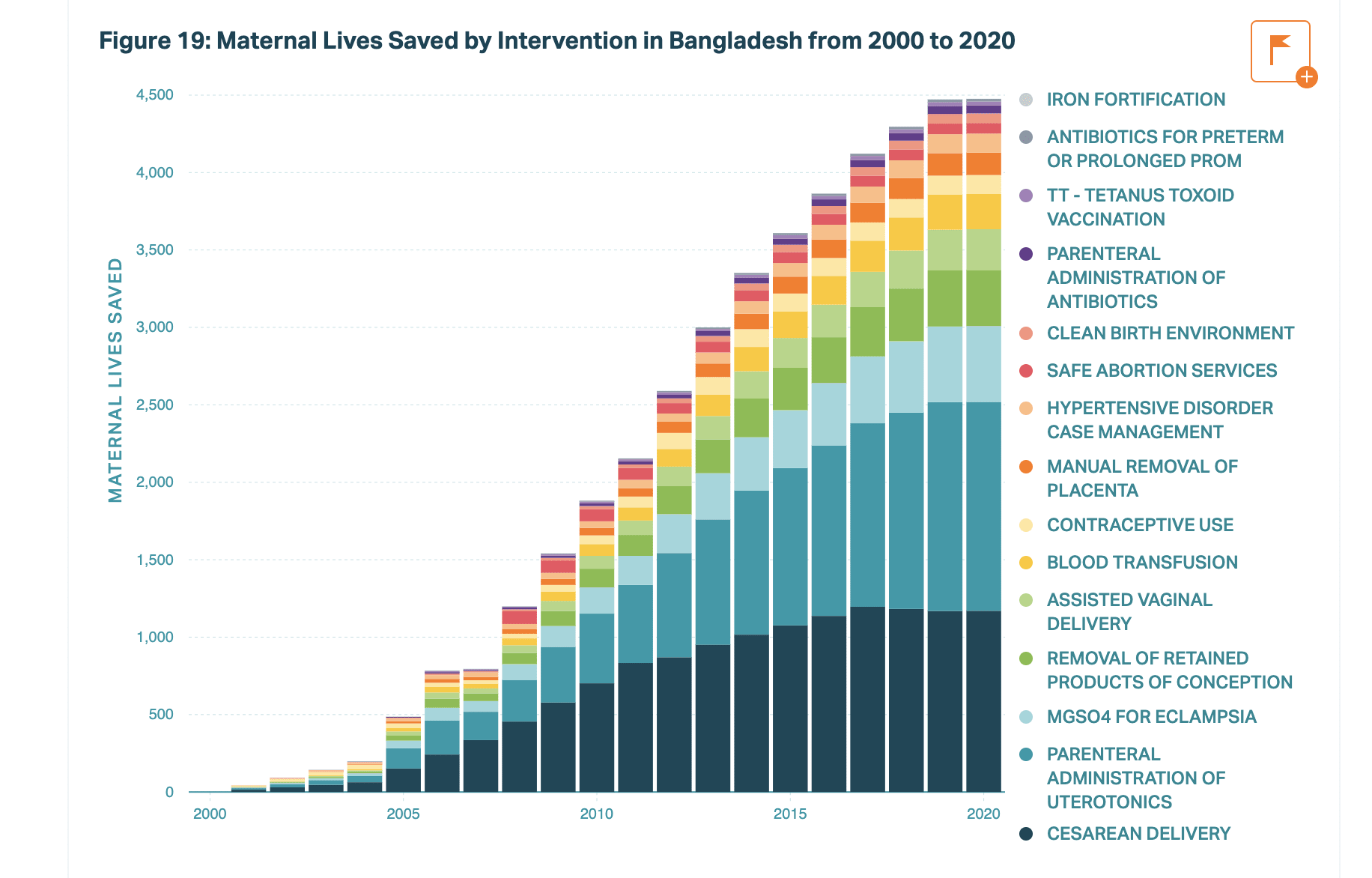

A development practitioner once quipped to me “You could do any intervention in Rwanda right now and it would probably work great”. NGOs have clamoured to work in Rwanda because their programs were likely to actually work there, even when it might fail in Uganda or Nigeria. Although I don’t know that much about the country, Bangladesh Kerala and Thailand seem to be similar with many development interventions working well across all sectors.

When a country (like Rwanda or Bangladesh)

1. Has better institutions

2. Cracks down on corruption

3. Collaborates with NGOs throughout their government system

With these in place, Healthcare and other interventions are likely to succeed. We can look to success stories of countries for weak guidance, but I don’t think we should consider one intervention working in these countries a strong data point that it will work in another. As a historical example Microfinance initiatives fell into a trap trying to replicate success in Bangladesh across Africa, with more failure than success.

IMCI and other guidelines have enormous potential

“IMCI” is at its core just a guideline for diagnosing and treating kids correctly (see diagram above) and a great one at that. When there has been a successful “IMCI” implementation, in simple terms that means that nurses who were diagnosing and treating patients badly, now follow guidelines which make sure they treat them well. Guideline based healthcare is a hugely under-resourced and under-researched area. I would almost go as far as to say that well implemented guidelines are the only way to achieve “correct diagnosis and treatment” in many low-income countries.

As we task-shift and expect nurses and community health workers to manage patients, flowchart based guidelines are the best way of simplifying and clarifying the new, more difficult work we expect these lower level health workers to perform. We do however need carrots and sticks for health workers to make guidelines work, so the worse the health system is in general, the harder guidelines like IMCI are to implement and maintain.

Light Disagreements

Community Health workers are often not cost-effective

I agree that CHWs are an essential, scalable part of many LMIC health systems. CHWs however are touted to be very cost-effective when they often aren’t. This statement made my eyes pop a little. “Many studies have found CHW programs to be cost-effective by various metrics. In Mozambique, the annual cost per beneficiary was just $47.12”.

50 dollars is a HUGE cost to serve just one beneficiary. In 2010 Mozambique’s health spend per capita was around $30 dollars. This means that to pay for a CHW to provide basic care for one patient, Mozambique would spend more than its per capita allocation, an expense that doesn’t make sense for a low income government.

By nature, CHWs are relatively expensive health providers because they treat few patients per month. They can’t treat large numbers because they only treat a handful of conditions in young children and can’t treat most of the disease burden. They also operate in small geographical areas. Although data is hard to find, cost per patient treated by orgs like LastMile Health, Muso and Living Goods seems to vary between about $5 and $12 which is more expensive than patients treated at static government facilities, or at our OneDay Health Centers ($2 per patient).

To further emphasise (from RP's appendix)

“Per $10,000 invested, CHAs delivered over a thousand home visits, 370 child cases of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhea treated, 65 pregnancy home visits, 331 malnutrition screenings for children under five, and provision of family planning access to 117 women.”

These numbers might look good at first, but to use the example I know best, our OneDay Health Centers are set up for $4,000, and within just a year treat 1500 patients on average, including about 400 kids with malaria, pneumonia and diarrhea. After that they continue to treat that many patients year on year at a lower cost.

LMH is far more well known and better funded than Living Goods

“LMH is perhaps a bit less well-known compared to a related CHW program called Living Goods (which has already received several Open Philanthropy grants)”.

Last Mile Health are the most well funded, well known and celebrated CHW organisation in the world - they won both the TED prize and the multi-million dollar Skoll award in 2017. They are far better known in the public health world than Living Goods. Their co-founder and Head Raj Panjabi is on the board of the Skoll foundation and has worked in the President’s office.

Transitioning to government ownership is a risky bet - that might sometimes be worth it

“We think this (funding LMH programs) represents an example of a catalytic grant opportunity for Open Philanthropy: to help fund and establish a public health program until it is transitioned to national government ownership.”

This comment here is perhaps naive - transition to government ownership is indeed the cliche path to scale (and dream) for many of us in the social enterprise world, but it rarely happens.

The idea that Open Philanthropy could pick a country, and fund community health workers until the government takes over sounds great but has a very low chance of success. I’m not saying its necessarily a bad bet, but it would be vhigh risk. There are already hundreds of millions of dollars pouring in to fund attempts to transition CHWs to government ownership. Why would OpenPhil be better at this than the other funders?

I do agree though that LastMile Health are one of the best orgs around at making this pathway happen and they have at least partially succeeded with it in a handful of countries. They have done better at government adoption than most organisations

Supply Chains interventions have largely failed.

I agree that there is potential with supply chain interventions, but think the overall record of supply chain interventions are poorer than RP paints. The failures may at least match the successes. Chemonics spent 10 Billion Dollars of USAID money on trying to improve supply chains and on review achieved very little. Also I’m skeptical of RidersForHealth. My feeling is they are now solving a problem that no longer exists at scale. To their credit they were part of solving an important problem 30 years ago when there was no good way of getting medications to facilities, but now that’s pretty straightforward through an abundance of private motorcycle taxis. I don’t understand how an NGO in this area can now add much value outside of a few niche cases.

I do agree though that there could be some excellent opportunities. After all, having medicines at the health facility is the no. 1 necessity before we even think about anything else. On this front I think Access to Medicines initiative have a logical approach to improving family planning commodities, although they are still a very new org.

Again I really like the RP report and would love to comment more, but don't have time! Keen for discussion and comments as always!

While I agree this is true in theory, is it practical? I imagine the size needed to power such a study is prohibitive except for the largest organisations, the answer still wouldn't be definitive (eg due to generalisation concerns), and there would be lots of measurement issues (eg residents in one district crossing to another district with better funded healthcare).

If you tell me I'm wrong, I'd definitely bow to your experience and knowledge in this field but this isn't obviously true.

I don't have great experience and knowledge here AT ALL as a caveat. Never "bow" to anything I say, my takes are often more on the "loose" than "rock solid" end of things :D.

I think if we can randomise things like socrecard studies and IMCI across hundreds of health facilities (done a number of times), then I don't see why we can't do the same with a supply chain interventions or governance interventions. The community Health worker movement has done some impressive large scale RCTs like this one. Perhaps 1-3 million dollars could make these studies happen... (read more)