Editorial noteThis report is a “shallow” investigation, as described here, and was commissioned by Open Philanthropy and originally produced by Rethink Priorities from September to October 2024. Open Philanthropy does not necessarily endorse our conclusions, nor do the organizations represented by those who were interviewed.

Our report focuses on exploring health systems strengthening (HSS) as a potential new cause area for Open Philanthropy. We examined a range of interventions to improve health system performance, analyzed case studies of successful systems in low- and middle-income countries, and highlighted promising opportunities for philanthropic funding. We reviewed the scientific and gray literature and spoke with six experts to describe the state of the field as of late 2024. In early 2025, we revised the report for publication; we also added a short addendum based on a second round of interviews with a different group of experts to incorporate updates related to the recent USAID developments.

We don’t intend this report to be Rethink Priorities’ final word on health systems strengthening. We have tried to flag major sources of uncertainty in the report and are open to revising our views based on new information or further research. |

Executive summary

Scope

This project investigates health systems strengthening (HSS) as a potential cause area, aiming to provide both a high-level overview of the field and actionable insights into specific interventions and grantees. A key goal is to identify promising opportunities for philanthropic funding that improve health systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Research process

We began by identifying and categorizing a wide range of HSS interventions based on the scientific and gray literature, previous analyses by Open Philanthropy and Rethink Priorities, and expert consultations. These interventions were organized in a spreadsheet and the evidence base for (cost-)effectiveness was evaluated. From this, we selected six particularly promising interventions for deeper review, including by creating rough cost-effectiveness models.

To complement this review, we conducted case studies on five countries or states that have achieved notable health outcomes despite low expenditure, highlighting successful HSS approaches as well as other factors that contributed to their success. Two implementing organizations were also spotlighted for their potential, and insights from six experts informed the broader analysis.

Key findings

Shortcomings in LMICs healthcare systems cause 5.7-8.4 million avoidable deaths annually, with 60% due to poor quality of care and 40% due to non-utilization. Despite the scale of the problem, funding for HSS remains “inefficiently low,” according to an expert that we interviewed. Persistent systemic weaknesses call for long-term, large-scale interventions beyond quick fixes or disease specific approaches.

Country case studies suggest that HSS reforms, including commitments to primary healthcare and universal health coverage, have plausibly contributed to recent health improvements. Notable shifts include funding for maternal and child health (e.g., Integrated Management of Childhood Illness [IMCI]), vaccines, pro-poor initiatives reducing out-of-pocket costs, and community led-programs like community health workers (CHWs). However, these gains must be contextualized within broader changes like economic growth.

Evaluating HSS remains challenging due to its complexity and system-wide nature. Evidence tends to focus on discrete interventions like service delivery and CHWs, while systemic areas such as financial reform, health information systems, and supply chain management are understudied.

After completing the first draft of this report, we conducted additional interviews, in which we discussed the implications of the large-scale withdrawal of USAID funding from health systems programming. Experts emphasized that USAID had historically been one of the largest funders of technical assistance, data systems, and drug supply chains in LMICs. Its abrupt exit has created substantial gaps in core health system functions. While this shift was not the original focus of our review, it may present a promising opportunity for philanthropic leverage. Targeted short-term investments in technical assistance or health information systems could stabilize essential programs, preserve institutional capacity, and shape longer-term reform trajectories. These may not be cost-effective under normal circumstances but could be among the most strategically valuable interventions available in the current moment.

We categorized HSS interventions into six building blocks—service delivery, health workforce, health information, supply chains, financing, and governance—and profiled six interventions (see Table 1 for a summary of our findings):

- IMCI and IMCI supervision/mentorship: IMCI appears highly cost-effective for improving child health outcomes, but it is not neglected. However, IMCI mentorship and supervision can significantly amplify existing programs’ effectiveness, making this a promising candidate for grants, especially in underserved areas.

- Community scorecards (CSCs): These tools foster community accountability, improving service delivery and outcomes when implemented in the right contexts. They are scalable and relatively low cost, making them a potentially promising intervention for philanthropic investment.

- Drug delivery system reforms: Reforms have shown increases in drug availability and cost savings, but direct evidence linking these changes to health outcomes is lacking. A rough model suggests they may be cost-effective, and more tractable than we expected.

- CHW programs: CHW programs may still offer significant room for improvement, particularly through the integration of mobile health (mHealth) and other care innovations. However, they are not neglected in general, and high costs and sustainability concerns may limit their appeal compared to more neglected interventions like IMCI mentorship.

- Continuous quality improvement (CQI): While these interventions show promise in enhancing clinical processes, their lower cost-effectiveness, lower tractability, and unclear impact on health outcomes make them less attractive as grant opportunities compared to other HSS interventions.

We tentatively recommend the following directions for further exploration:

- IMCI mentorship and community scorecards: Prioritize further investigation to identify the most promising grant opportunities.

- Drug delivery and supply chain reforms: Explore this further by focusing on specific contexts with pronounced supply chain challenges to identify impactful and feasible interventions.

- Innovative pilots: Identify and consider funding promising small-scale pilot programs to test new strategies, e.g., in supply chain and drug delivery system improvements.

- Governance, financing, and information systems: Investigate these high-leverage areas further, including support for local think tanks, policy guidance, and health information systems.

- USAID gap stabilization: Consider one-time, short-term grants to prevent critical systems from collapsing in high-risk countries affected by the USAID withdrawal. This could include support for technical assistance, facility-level financing, or basic data infrastructure in places where continuity funding is unavailable and the risk of institutional deterioration is high.

Key uncertainties

- Intervention blind spots: We are uncertain whether we identified the most promising interventions or overlooked others that might be even more impactful. Our review was skewed toward well-established interventions with high-quality evidence, potentially under-exploring more novel, complex, or harder-to-evaluate options that may also be more neglected.

- Future applicability of case studies: As LMICs undergo an epidemiological transition, shifting from a focus on infectious diseases to more complex non-communicable diseases, this might limit the forward-looking applicability of the lessons learned from historical case studies.

- Uncertainty in grant potential: While we identified several possible grant opportunities, we did not have time to investigate them in detail. As a result, we are unsure which opportunities are the most promising.

- Skew toward established grant opportunities: Our exploration was likely biased toward well-known, easy-to-find grant opportunities, potentially missing more neglected or novel options. We are also uncertain how best to identify emerging opportunities beyond maintaining contact with experts in the field.

Health systems strengthening as a cause area

Shortcomings in LMIC health systems are large and comparatively neglected

Health system shortcomings in LMICs are large, and there has been limited progress in recent years. Here are some figures to illustrate this:

- Nearly 2 billion people have no access to essential medicines, meaning that the medicines are either unavailable, unaffordable, inaccessible, or of low quality (Chan, 2017). Drug shortages are common in LMICs (Shukar et al., 2021).

- Cameron et al. (2009) found that the average availability of medicines in public health facilities across WHO regions ranged from only 29% to 54%.

- “In 2019, out-of-pocket health spending dragged 344 million people further into extreme poverty and 1.3 billion into relative poverty” (WHO, 2023).

- Health information systems are still underdeveloped in many countries. Only about half of LMICs have a “well-developed or sustainable capacity for surveying populations and health risks” (WHO, 2021).

- Many health facilities are inadequate. According to WHO (2020), “one in 8 health care facilities has no water service, one in 5 has no sanitation service, and one in 6 has no hand hygiene facilities at the points of care.”

- The WHO estimates a “projected shortfall of 10 million health workers by 2030, mostly in low- and lower-middle income countries” (WHO, 2023).

- The WHO and World Bank’s (2023) global monitoring report on universal health coverage found that improvements to health system coverage have stalled in the last decade, and the proportion of the population facing catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditures has even increased. Notably, this is not all due to the Covid-19 pandemic, as the report called the situation “alarming” even before the pandemic hit.

The WHO (2020) estimates that better healthcare could save between 5.7 and 8.4 million lives in LMICs each year. Of those avoidable deaths, 60% are due to poor quality of care, and the other 40% are due to non-utilization of health care. Thus, simply improving healthcare infrastructure or access alone would not even eliminate half the mortality burden, as most of the death toll is due to quality of care issues, such as mismanagement and misdiagnosis of diseases, delays in care received, non-adherence to clinical guidelines, and in some cases even abuse.[1] Kruk et al. (2018) found that these issues exist across many diseases, which suggests that “health system-wide improvement is needed rather than disease-specific quality interventions.” Besides the health burden of weak health systems, the WHO (2020) also estimates that LMICs lose $1.4–1.6 trillion in productivity each year due to inadequate health systems. Given the size of this problem, a very rough estimation shows that even at 2,000x cost-effectiveness in Open Philanthropy’s terms[2], it would take more than $14 billion annually to solve the problem in all countries.

Given the magnitude of the problem, the development assistance funding for health systems strengthening is comparatively low. According to IHME (2021) estimates, total global Development Assistance for Health (DAH)[3] funding for HSS was ~$7.5 billion in 2021, about the same amount as HIV/AIDS funding.[4] However, HIV-related mortality is only about one tenth of the mortality related to shortcomings in overall healthcare access and quality.[5] The share of total DAH funding for HSS decreased from ~20% in 1990 to ~10% in 2021. In a conversation, Margaret Kruk, Professor of Health Systems at Harvard University, described total funding for health systems in LMICs as “inefficiently low”. Moreover, Rakesh Parashar, Assistant Professor in Global Health Systems and Policy, noted that, since the pandemic, the “momentum has shifted away” from the fundamental requirements of strengthening routine health systems, and towards pandemic preparedness.

Donors often favor funding vertical,[6] disease-specific programs rather than HSS interventions due evaluation challenges. As we describe below, it is inherently challenging to evaluate complex, large-scale HSS interventions. Moreover, nearly all of the experts we spoke with agreed that cost-effectiveness is not the right metric to evaluate the success of health systems interventions, but did not seem to agree on better objective metrics. As a result, the dearth of measurable outputs makes it harder to find funders for the space. Instead, the experts argued, donors seeking quick wins may prefer the more immediate returns of vertical interventions, which are easier to monitor and evaluate.

In our conversation, Parashar argued that most funders prefer “if you can give them tangible outputs, tell them that X will lead to Y and then to Z—some clear hypothesis on what the intervention is going to lead to”. However, he explained, HSS is fundamentally different from vertical interventions because it involves long-term investments and building systems which interact with many variables and do not immediately or directly translate to health outcomes. Parashar argued that funders need to recognize that HSS involves complexities and may not fit neatly into cost-effectiveness frameworks, but that the interventions remain crucial for sustainable health improvements.

Moreover, funding for HSS is skewed toward relatively few health system building blocks. According to Kraus et al. (2020), almost 40% of HSS funding was spent on service delivery, whereas supply chains received only about 7% of HSS funding. We are unsure why that is, but we suspect at least part of the reason is that service delivery seems more tangible and has more immediate outcomes, whereas supply chain interventions tend to be longer-term, more complex interventions, with less immediately observable impacts.

What is health systems strengthening?

There is no clear consensus on the definition of health systems strengthening (HSS), but a commonly used (though very vague and broad) definition is the WHO definition of HSS as “any array of initiatives that improves one or more of the functions of the health systems and that leads to better health through improvements in access, coverage, quality or efficiency” (Witter et al., 2019).

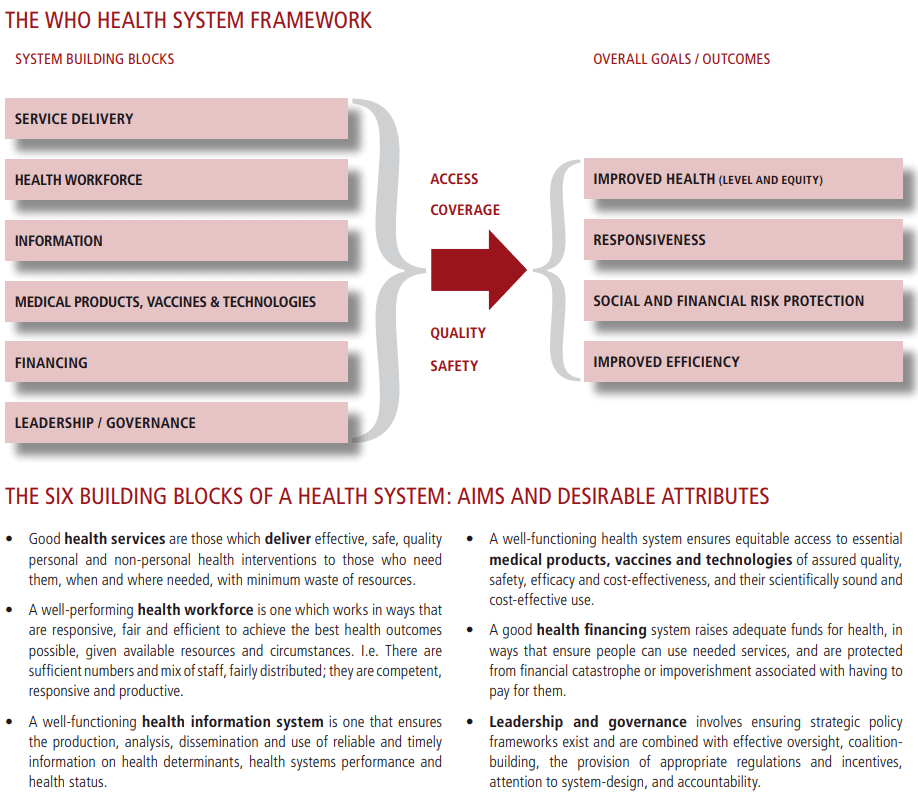

In this report, we generally rely on the WHO (2007, p. 3) framework to categorize health systems strengthening interventions. According to this framework, a health system consists of 6 components or “building blocks”: (1) service delivery, (2) health workforce, (3) information, (4) medical products, vaccines & technologies, (5) financing, (6) leadership / governance (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: The WHO health system framework

Note. From WHO (2007, p. 3)

We also roughly follow Witter et al.’s (2019) inclusion criteria for what constitutes an HSS intervention:

- Scope: effects cutting across building blocks, tackling more than one disease

- Scale: having national reach and cutting across several levels of the system (though we also consider initiatives with regional or state reach in large countries)

- Sustainability: sustained effects over time and addressing systemic blockages

- Effects: impacting on outcomes, equity, financial risk protection, and responsiveness

A taxonomy of typical HSS interventions

Different actors have very different approaches and interpretations of HSS.[7] The labeling of HSS is not always meaningful and often used for disease-specific interventions (Marchal et al., 2009). Nonetheless, we think that typical HSS interventions across the six building blocks are (based on Witter et al., 2021):

Leadership / governance: Governance is a cross-cutting health system function that underlies and enables all the other “blocks” of HSS; thus, governance-related interventions usually affect several other blocks. Interventions mentioned in the literature typically fall into one of three buckets:

- Governance and leadership-centered, e.g., leadership training / mentoring / peer support; clinical governance interventions (e.g., appropriate use of guidelines); and community participation (in e.g., decision-making and priority-setting)

- “Governance plus” (paired with interventions in other blocks), e.g., training for community-based care to support patient treatment; design and implementation of community-led delivery models; and decentralization of delivery / financing

- Governance policies and reform programs seeking a whole-system change that aim to address multiple diseases and are often large-scale and implemented over long time periods, e.g., formulation and enactment of national policy; interventions to enact effective legal and administrative framework; and anticorruption interventions.

Workforce: Interventions related to the workforce typically fall into four categories:

- Workforce supply, e.g., pre-service education and training; or higher pay

- Workforce distribution, e.g., retention packages for staff in underserved areas using various (e.g., financial) incentives

- Workforce performance, e.g., in-service training, pay-for-performance schemes; and management / supervision

- Skills mix / task shifting, e.g., shifting some tasks of highly-skilled health personnel to lower-skills personnel or community health workers / volunteers

Financing: Interventions related to financing can roughly be grouped into four categories (though interventions typically cover several of these categories):

- Revenue raising / pooling, e.g., insurances, health equity funds; and user fee exemptions

- Purchasing, e.g., performance-based financing; and demand-side financing (e.g., vouchers, cash transfers)

- Benefit package design and service provision, e.g., basic packages of health services; and regulation, especially of non-state providers

- Cross-cutting issues such as governance and public financial management, e.g., improving governance (e.g., transparency and accountability); and public financial management

Health information: Health Information systems (HIS) include “health data sources required to plan and implement national health strategies. These include electronic health records for patient care, health facility data, surveillance data, census data, population surveys, vital event records, human resource records, financial data, infrastructure data, and logistics and supply data” (p. 56) and are used to inform health programs. HIS strengthening interventions relate to interventions improving the quality and use of data that aim to improve the “availability of high-quality data used on a continuous basis for decision-making at all levels of the health system” (p. 56), e.g.:

- eHealth interventions, e.g., establishing health record platforms, lab and pharmacy management information systems, clinical decision support tools

- Development, adaptation, or deployment of information technologies

- Information technology support (e.g., help providers convey health promotion messages)

Supply chain strengthening: Interventions related to improving supply chains include, e.g.:

- Improvements to supply chain management to reduce stock-outs and loss due to expiration

- Bulk or pooled procurement of medicines

- Training of pharmacists and providers to improve stock management

Service delivery: Interventions to “strengthen health services are aimed at improving the provision, quality, utilisation, coverage, efficiency, and equity of health services, with the view to improving effectiveness and achieving the intended health outcomes” (p. 64). Example interventions are, e.g.:

- Organizational strengthening (e.g., improvement of referral systems)

- Service redesign (e.g., improving community-level delivery of health services)

- Demand generation at the community level

- Co-production and integration of services

Challenges in evaluating HSS interventions and their cost-effectiveness

We have found that the larger the complexity and scale of an HSS intervention, the more scarce is information related to the direct effects and clinical outcomes associated with it. As a result of this, our review is fairly skewed towards smaller, less complex, easier to evaluate interventions. In our interviews, experts confirmed that measurability is a consistent issue within HSS interventions, with more systemic and indirect reforms facing particular difficulties in reporting on effectiveness. Parashar noted that in the health systems space, “it can be hard to pinpoint the relationship between interventions and health outcomes.”

Moreover, many studies do not evaluate HSS interventions comprehensively, but only focus on a few narrow outcomes. Thus, we expect that narrow, outcomes-focused studies would tend to underestimate the overall effects of an intervention.[8] As Witter et al. (2021) put it: “Many studies focus on one element within health systems and fail to describe the wider effects of an intervention, thus inadvertently ‘verticalising’ what is in fact an HSS intervention.”[9] The degree of underestimation is likely highly intervention-specific and hard to guess.

In addition, some experts think that unit cost-effectiveness is the wrong metric to assess the success of large-scaled projects. As Kruk put it, “there’s an inherent tension between scaled reforms (with long time scales) and unit cost-effectiveness”. Kruk mentioned in a conversation that some of her colleagues at the Harvard Chan School attempt to model cost-effectiveness and perform sensitivity analyses, but that she considers such models “mostly just useful for orders of magnitude.”

Likely as a result of these difficulties, both academics and practitioners seem to resist attempts to directly measure cost-effectiveness, particularly at the intervention level. Adeel Ishtiaq, Program Director at R4D, explained in a conversation that “people [in the space] realize that system-strengthening is a long-term process-focused agenda, and would struggle to assess the specific cost-effectiveness of one individual project, but can compare one situation to another to identify where improvements have been made”. Kruk argued “the right angle is affordability, rather than cost-effectiveness. What can the government afford, and on what time scale?”

Country case studies: Lessons from high-performing health systems

As a first stage attempt to identify markers of success, we pursued several case studies which others have highlighted as high-performing health systems relative to their spending and level of development: Bangladesh, Thailand, Ethiopia, Ghana, and India’s Kerala state.

We chose the five case studies based on our initial impression of the literature, in which each had been frequently cited as an example of success in health systems reform, or for particularly good health outcomes at relatively low cost. However, we are only moderately confident that our chosen countries are the right selections to inform further research on health systems strengthening. We also asked each of our interviewed experts for their recommendations on valuable case studies, and compiled their responses at the end of this section.

Two sources have been particularly useful for this exercise. Good Health at Low Cost (Balabanova et al., 2011), initially published in 1985 and thoroughly revisited in 2011, explores several case studies in depth, and has driven some of our focus on these countries in particular. Exemplars in Global Health is an ongoing project which explores exceptionally well-performing LMICs across a range of outcomes, including under-5 mortality, neonatal and maternal mortality, family planning, and primary care. We encourage interested readers to look through their detailed reports on many of the countries and interventions discussed below.[10]

Throughout the case studies, we have attempted to portray the impression from the literature and to report the results discussed in the relevant papers. However, causal attribution is difficult. As a result, we have not been able to determine clearly the extent to which different interventions contribute to outcomes, and simply state here the claims found in the literature.

Our country case studies indicated that a large share of health improvements in positive-outlier countries were likely driven by non-health system factors (e.g., economic growth, political stabilization, improved education). However, health system strengthening seems to plausibly have played a key role as well, though we cannot be certain about the causality. Part of this appears to be related to spending—expenditures on healthcare, globally and in the countries studied, has increased ~4% real annually (Arize et al., 2024).

In terms of health systems interventions, points of commonality between high performers include a focus on maternal and neonatal health, increased access to care through community health workers and health service extensions, reductions in out-of-pocket costs, the involvement of NGOs, and integrated care (particularly integrated management of childhood illness, or IMCI). Our impression is that some of these approaches may be particularly promising interventions, which we have noted in our interventions spreadsheet. In addition, economic and social development, as well as the associated drops in fertility and increases in spending, appear to be important factors in understanding the changes each country has experienced in recent decades.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh has long attracted attention for its progress in improving health outcomes since its tumultuous independence in 1971 (Balabanova et al., 2011). The country has made significant progress in reducing mortality rates, improving life expectancy, and addressing adolescent fertility (Sultana et al., 2021; Asadullah et al., 2013). Indeed, the infant mortality rate fell from 137.76 to 42.24 per 1,000 live births over the period 1976-2010 (Asadullah et al., 2013).

The literature often attributes this success to socioeconomic changes as well as broad health interventions and community-based approaches (Balabanova et al., 2011). One key non-medical factor cited is rapid gains in wealth and parental education, which appears to have reduced both fertility rate and child undernutrition (Headey et al., 2014; Sultana et al., 2024).

Bangladesh has focused on reducing maternal and neonatal mortality through a holistic health-based approach. The strategy includes community-based family planning programs (which has successfully facilitated a reduction in the fertility rate,[11] explored in Ángeles et al., 2006 and discussed in Balabanova et al., 2011), increased access to healthcare facilities,[12] and the formalization of midwifery as a profession (Hossain et al., 2024). The integration of maternal health services with broader population policies and women’s empowerment initiatives has also been seen as critical in improving life expectancy and reducing maternal and child mortality (Sultana et al., 2024). Bangladesh has also prioritized vaccination programs and infectious disease control (Mor, 2022; Balabanova et al., 2011).

Additionally, Bangladesh has been home to many health innovations. These include electronic systems such as unified national health data systems and personal health records (Khan et al., 2019). Jo et al. (2021) found that mCARE, a digital health intervention package on pregnancy surveillance and care-seeking reminders, averted a DALY for $462.[13] Some organizations in Bangladesh, particularly local NGOs such as BRAC and icddr,b, have innovated also low-cost medical technologies and techniques[14], which drive down costs and have been demonstrated to improve patient outcomes (Chowdhury & Perry, 2020; Balabanova et al., 2011).

Primary healthcare programs led by NGOs,[15] especially in rural areas, have also been cited as providing reproductive and child health services and reducing neonatal mortality (Mercer et al., 2004). Government-supported NGO-run primary healthcare programs began in 1988 under the Bangladesh Population and Health Consortium (BPHC), and involve health workers making regular visits to underserved households to provide “basic health and family planning counselling [and contraceptives], oral rehydration salts, and mobilization of women to use satellite clinics and higher level facilities” (Mercer et al., 2004). Donor funding and high-profile “champions”[16] for newborn health have supported efforts towards community-driven healthcare initiatives to reduce child mortality (Rubayet et al., 2012).

We spoke with Mehadi Hasan, a Programme Manager at BRAC’s Health Programme, which focuses on primary care and particularly maternal and child health. He confirmed that organizations like BRAC have been significant players in the country’s healthcare sector, but also said that recent efforts have focused on improving state capacity to deliver care, slowly transitioning away from a dependence on NGOs.

Thailand

Thailand has also seen remarkably good health outcomes given its historical level of development and its relatively low spending on healthcare (Mor, 2022; Pachanee et al., 2014).[17] Ishtiaq highlighted Thailand as an exemplar of cost-effectiveness in health systems, and noted that Thailand now provides advisory support to other countries, positioning it as a leader in sharing best practices for cost-effective health system improvements. As in Bangladesh, some sources highlight Thailand’s process in non-health factors, such as economic growth, poverty reduction, state institutional capacity growth, and female literacy as key drivers of health improvement (Balabanova et al., 2013).

Thai public health leaders have shown remarkable continuity of vision over the decades, allowing for continuous development of pro-poor, pro-rural policy (Tangcharoensathien et al., 2018; Balabanova et al., 2013). When we spoke with Ishtiaq, he noted that the country’s strong health technology agency plays a crucial role in guiding the country’s healthcare system, enabling it to efficiently allocate resources and offer high-quality care at a lower cost. Furthermore, Thailand’s healthcare system has largely been driven by a focus on universal access, particularly for mothers and children (Balabanova et al., 2013), with strategic purchasing practices to keep costs low.

The Thai system is based on universal access at minimal cost and inconvenience. A crucial part of Thailand’s Universal Health Coverage (UHC) system is the “30 Baht Scheme,” which drastically reduced out-of-pocket expenses by allowing patients to access healthcare services for a nominal fee (Towse et al., 2004). This 2001 reform targeted 18.5 million previously uninsured Thais and dramatically improved financial equity in health access, especially in rural areas (Towse et al., 2004; Damrongplasit & Melnick, 2024). Local “district health systems” ensure that all Thais have “geographically accessible” healthcare, including both clinics and hospitals within a reasonable distance. Since 1972, all medical graduates enter compulsory rural service, simultaneously ensuring rural access and reducing international brain drain (Thammatacharee et al., 2013; Balabanova et al., 2013). By merging multiple public risk protection schemes and shifting funding away from major urban hospitals toward primary care facilities, the government opened access to essential health services for all populations (Towse et al., 2004; Limwattananon et al., 2007).

Strategic purchasing practices under the UHC, specifically within the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS), further contributed to Thailand’s ability to maintain low healthcare costs while delivering quality care. The UCS pools financial resources and negotiates contracts with healthcare providers to promote cost efficiency (Nonkhuntod & Yu, 2018). This cost efficiency is especially evident when compared to Thailand’s Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme, which serves a wealthier population at a higher cost per patient (Patcharanarumol et al., 2018).

In addition to cost and convenience, Thailand’s health system reforms focused heavily on maternal and child health. By the 1990s, the country had achieved universal coverage for key maternal and child health services, such as free antenatal care and skilled birth attendance, resulting in dramatic improvements in critical health outcomes (Balabanova et al., 2013).[18] These gains were achieved through comprehensive maternal care, family planning initiatives, and widespread public health campaigns, which improved both access and awareness regarding maternal and child health issues (Gruber et al., 2014).

Ethiopia

Ethiopia moved to a transitional government in 1991 after decades of political upheaval and tragic drought and famine. Since then, the country has achieved remarkable success in improving public health at low cost: the maternal mortality rate fell from 953 to 267 per 10,000 live births between 2000 and 2015 (driven by a reduction in deaths due to abortion, miscarriage, and infection), and the under-five mortality rate decreased by 56 percent in the same period (EGH, 2024a; EGH, 2022). Such success has often been attributed to its strategic focus on community-based interventions, robust political support, and a commitment to expanding primary health care (PHC) services.

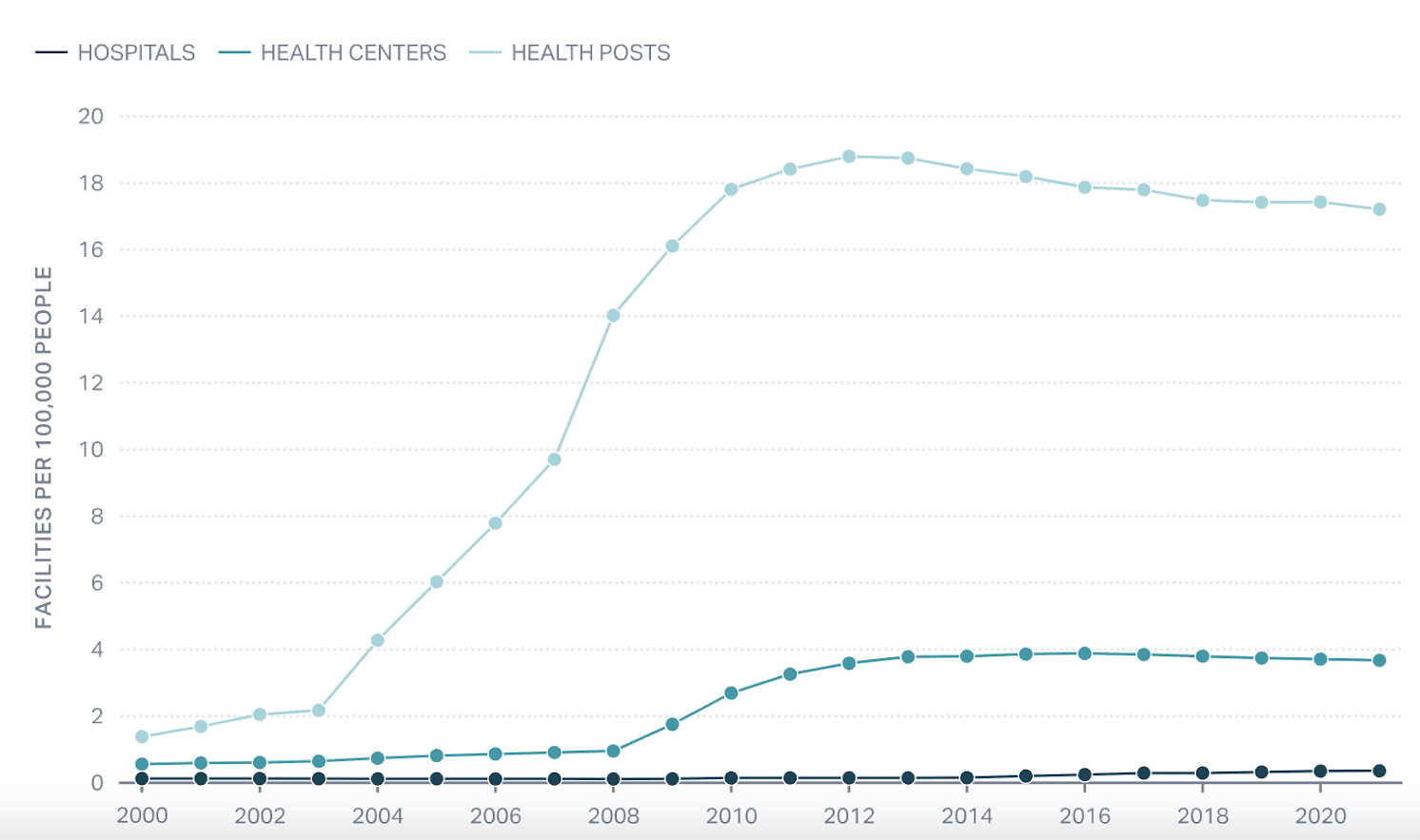

A key component of Ethiopian healthcare strategy is the Health Extension Program (HEP), which deployed over 33,000 Health Extension Workers (HEWs) to rural areas, delivering a package of preventive and curative services directly to communities at health centers and “health posts” (Østebø et al., 2018). Figure 2 below illustrates the massive increase in the number of healthcare facilities available since 2000, although this progress seems to have slowed and even reversed in recent years.

Figure 2: Health facility density in Ethiopia from 2000 to 2021

Note. Taken from Exemplars in Global Health (EGH, 2024b)

The HEP emphasized improving household behaviors, community health education, and the use of “health posts” for primary care, which have been credited with reducing maternal and child mortality (Wang et al., 2016; Workie & Ramana, 2013). Ethiopia’s specific efforts to reduce under-5 mortality have focused on working within the HEP to scale up access to individual evidence-based interventions such as the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-10) and Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) including the use of oral rehydration salts (Drown et al., 2024).

The HEP has received broad acclaim, but, especially in the last ten years, critiques have emerged, particularly as service expansion has stalled. Some critics note that it has been carried out within an authoritarian context, and that the methodological implications for studies of the program’s impact may call data quality into question (Østebø et al., 2018). Others note that some communities tend to bypass HEWs and health posts when seeking care, and that service and training improvements are needed to maximize the benefit of the HEP (Haileamlak & Ataro, 2023). Our impression is that the HEP is still largely beneficial and a positive example of the CHW and service extension models of care provision, which we explore in more detail in a later section.

In addition to the HEP, Ethiopia introduced Community-Based Health Insurance (CBHI) in 2011, with the intention of increasing healthcare utilization and reducing the financial burden on rural populations. The CBHI improved access to outpatient services and helped advance universal health coverage by ensuring that low-income populations could afford healthcare. However, enrollment is not universal and is impacted by measures, such as education, perceived quality of care, and convenience of accessing care (Mebratie et al., 2019; Atnafu et al., 2018). Our weakly held impression is that the community broadly sees the HEP as more successful than CBHI schemes.

Pro-poor policies, including free maternal and child health services and the elimination of markups on essential medications for non-communicable diseases, further supported equitable access to healthcare (Admasu et al., 2016; Banteyerga et al., 2011). Decentralizing healthcare delivery and empowering communities to take ownership of health initiatives have been lauded as contributing to sustainable improvements in health outcomes at a low cost (Admasu et al., 2016; Croke, 2020). Furthermore, Ethiopian policies are intended to allow for synergies between various health initiatives, with the hope that global efforts to fight HIV/AIDS, malaria and TB can also drive improvement in maternal and child health (Banteyerga et al., 2011).

Several papers comment on indicators of good governance present in the Ethiopian health system. Exemplars in Global Health note that the country’s health efforts have benefited from the “availability of significant donor and partner resources, and the government’s ability to coordinate these resources effectively.” In addition, active efforts (exemplified by the Ethiopian Health Sector Development Programme) to include the perspectives of a wide range of stakeholders have been lauded (Banteyerga et al., 2011). Furthermore, donor-enabled initiatives have established data-driven district-level planning that informs national health plans (Banteyerga et al., 2011). The additional integration of multisectoral policies,[19] such as linking health initiatives with infrastructure and education, reinforced these health improvements despite Ethiopia’s low-income status (Assefa et al., 2020; Assefa et al., 2017).

Ghana

Ghana has made significant progress in improving health outcomes, particularly in reducing infant and under-5 mortality rates and increasing life expectancy (Saleh, 2013; Boachie et al., 2018; Adua et al., 2017). This improvement has been attributed to increased public health expenditure (Boachie et al., 2018) and to key initiatives, such as the National Health Insurance Policy, Free Maternal Care Policy, and Community-based Health Planning Services, and have enhanced access to maternal and obstetric health services (Adu & Owusu, 2023). Ishtiaq of R4D recommended Ghana as a strong example of successfully expanding healthcare access through health insurance coverage, reducing out-of-pocket payments, and providing key services free of charge.

Several Ghanaian reforms have focused on reforming healthcare financing to reduce out-of-pocket costs. One key program is the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), financed primarily through a 2.5% VAT on selected goods (Frimpong, 2013). The introduction of the NHIS has not only reduced maternal mortality but also improved infant outcomes by promoting facility-based deliveries (Adu & Owusu, 2023). In combination with the NHIS, the Free Maternal Care Policy, which provides free services such as antenatal care and skilled delivery (Adu & Owusu, 2023), ensures that pregnant women can access healthcare without facing the out-of-pocket costs that were common under the previous “Cash and Carry” system (Ibrahim & O’Keefe, 2014). Ghana’s early progress in scaling up health insurance and improving governance is notable, though Ishtiaq mentioned that coverage expansion has stalled in recent years. Furthermore, healthcare costs remain too high for some insured households, especially among the poorest populations and in poor regions (Okoroh et al., 2018).

Another critical component of Ghana’s maternal and child health strategy is the Community-based Health Planning Services (CHPS) initiative, a CHW intervention which trains community health workers to provide essential services[20] for rural and underserved populations (Adu & Owusu, 2023). These services are tailored to meet the specific needs of the community (Baatiema et al., 2016). Ghana has also prioritized child immunization and control of diarrheal diseases, both of which initiatives have contributed to the country’s declining under-five mortality rate (Ickowitz, 2012).

Ghana’s Essential Health Interventions Program (GEHIP) has made significant efforts for maternal and child health by partnering with international actors to implement district-level HSS interventions informed by prior Tanzanian programs (Columbia University, 2017). GEHIP involves training frontline health workers and creating robust emergency referral systems for mothers and newborns (Bawah et al., 2019). The workers are trained to deliver Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI, further discussed here), among other things. The program has been estimated to cut neonatal mortality in half by improving access to life-saving interventions at both community and facility levels (Bawah et al., 2019).

Kerala

Kerala’s health outcomes have long been a subject of international study, often referred to as the “Kerala model,” which showcases how strong public investment in health and social welfare can lead to impressive outcomes despite low per capita income. The state’s early achievements were said to be largely driven by welfare policies that emphasize education, land reform, and healthcare equity, ensuring that even marginalized groups receive access to essential services (Parayil, 1996; Nag, 1988). High public spending on health and education has historically supported this, allowing Kerala to achieve good health outcomes with relatively low per capita health expenditures compared to other states in India and other low- and middle-income regions (Kutty, 2000).

However, most literature we have found on Kerala’s outperformance is somewhat outdated, and it seems to be less of a positive outlier than it used to be—partially because it is now one of India’s more prosperous states and devotes considerable resources to its health care system through the Aardram Mission, launched in 2017 (Adithyan et al., 2024). Many of the articles we have found on Kerala focus on potential issues or areas of improvement, rather than on unexpected success.

A strong sense of political awareness and action among the population led to significant public pressure to maintain a high standard of care and a focus on equity (Nag, 1988). Kerala’s focus on primary healthcare, with the establishment of extensive networks of primary health centers (PHCs), ensured the widespread delivery of services, even in rural areas. However, while the decentralization of PHCs aimed to further improve health outcomes, it was found that local governments allocated fewer resources to health than the state government, limiting potential improvements in the health infrastructure (Varatharajan et al., 2004).

While, historically, public health systems provided the backbone of Kerala’s health achievements, rising privatization has led to increased costs and growing inequality in access to care, particularly in urban versus rural areas (Thankappan, 2001). As Kerala has an increasing share of public health issues related to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which require longer-term care and more specialized medical services (now often provided by the private sector), this may lead to serious health inequities (Narayana, 2012).

Finally, while Kerala has achieved remarkable health outcomes relative to its income, infrastructure is still a major driver of health inequity. The state government’s emphasis on welfare and infrastructure development throughout Kerala, rather than focusing on underdeveloped regions, has meant that regions with better infrastructure were better positioned to benefit from public action. This has created regional disparities in how effectively inputs like healthcare and education translate into better health outcomes (Jacob, 2014).

Valuable case studies recommended by experts

As part of our interviews with subject matter experts, we asked for their recommendations of exemplar countries that might be able to inform our understanding of the potential of systemic reform. Experts had difficulty identifying case studies with generalizable learnings, but did give some examples of countries which have achieved considerable improvements in their health system functioning. Many of them likely contain valuable insights, but all of them were recommended too late in our research process to include in full case studies. For those countries which we did not already include in our detailed case studies, we explain the experts’ reasoning below.

Rwanda

Rwanda is frequently cited as a country with impressive health systems progress, particularly in scaling up universal health coverage and community-based health insurance models. Its successes in reducing under-5 mortality are discussed in depth on Exemplars in Global Health. Ishtiaq noted that Rwanda has seen significant service coverage scale-up over the past decade. However, Ishtiaq also mentioned that Rwanda now faces reductions in external support, and will need to be more strategic in its purchasing, provider agreements, and government policies.

However, both Kruk and Douglas Call, Senior Program Officer at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, emphasized Rwanda’s unique characteristics—its small size, centralized governance, and high donor support—that make its successes less generalizable to other contexts. Call noted that public services are still often seen as inferior to private ones in the country. He referenced Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, as an example of how people “vote with their feet” by choosing private facilities and pharmacies over public health services, indicating a preference for private healthcare when public systems fail to meet expectations.

Sri Lanka and Cuba

Kruk mentioned Sri Lanka and Cuba as countries with notable health system experimentation. Similar to Rwanda, she emphasized that these countries are not very replicable due to their small size and autocratic political systems. Kruk argued that while these countries may have achieved good health outcomes, their models are less applicable to larger or more democratic nations.

South Africa

Ishtiaq praised South Africa for its impressive scale-up of HIV services, describing how the country transitioned from denialism to state-of-the-art HIV care over the past 15 years. This success has been primarily driven by domestic actors, which makes it an important case study for locally driven health system improvements. However, South Africa is now grappling with integrating its large HIV program into the broader national health system, as HIV services dominate the health budget. Ishtiaq pointed to this challenge as a key issue for South Africa moving forward, as it works to integrate vertical programs into a more holistic health system.

Vietnam

Ishtiaq also highlighted Vietnam for its progress in expanding its social security system, which has contributed to increasing health coverage. Vietnam is steadily building its health system, making it an interesting case study for countries looking to expand social health protections.

Highlighted HSS interventions

Our research and prioritization process

As a first step, we listed and categorized the various HSS interventions drawn from previous unpublished internal documents by Open Philanthropy and Rethink Priorities, developed during prior analyses. These interventions were organized into a comprehensive spreadsheet, where they were systematically reviewed, categorized, and prioritized.

We then used the following prioritization process:

- We deprioritized several interventions that have already been explored in previous work by Open Philanthropy and Rethink Priorities. This included most health workforce interventions, which were previously investigated in unpublished analyses by Open Philanthropy, and pooled procurement, a topic already addressed in a prior Rethink Priorities report on government procurement (Van Schoubroeck et al., 2024).

- We reviewed the evidence on the remaining interventions’ effectiveness and used this as a first prioritization criterion:

As a starting point, we used two systematic reviews (Witter et al., 2021; Hatt et al., 2015), as these appeared to be the most comprehensive recent reviews of HSS interventions. As this turned out to be an insufficient basis for prioritization by itself,[21] we also reviewed individual studies / case studies (see also our country case studies) in cases where the systematic reviews did not leave us with a clear picture of the evidence.

- After collecting evidence for a wide range of HSS interventions, we rated each one based on how promising we found the initial evidence to be (see column E in spreadsheet).

- We then agreed with Open Philanthropy on the top six most promising interventions to explore in more detail (in no particular order):

Finally, for each of the top interventions, we gathered more information and built a very rough model to get a sense of whether it could potentially meet Open Philanthropy’s cost-effectiveness bar. Our final analysis of each of these interventions includes arguments for and against, crucial considerations, organizations we have found working on similar interventions, and our takes on each. Note that we have not focused on explicitly exploring neglectedness and tractability beyond what is clear from the academic literature.[22] As a result, readers may find that we have prioritized some interventions that we would not have prioritized with a clearer initial view on tractability and neglectedness.

For each intervention, our rough models are included as separate tabs in the spreadsheet. Our models do not include estimates of null effects and other arguments against each intervention, so their effect sizes may be on the high end. To alleviate this concern, each model includes an opportunity for user input, to adjust the intervention effect according to the proportion of benefit that a “standard” or scaled-up version of the program would be likely to engender. One might think of this as an external validity adjustment for the studies assessed; an opportunity to incorporate the user’s assessment of the seriousness of arguments against the intervention’s effectiveness; or as an attempt to account for publication bias, large positive outliers, or other systematic biases in favor of the intervention in the literature.

As we note throughout, each model should be seen as a very rough guide to the order of magnitude of the cost-effectiveness that an intervention might be able to attain. We do not recommend that Open Philanthropy take these estimates as serious indicators of specific project effectiveness, but rather as guides to the general shape and scale of impact possible for each. It’s possible that our models omit larger systemic impacts since they draw from the narrow intervention-focused literature, but it’s also possible that our use of reported intervention effects overstates a program’s impact for a variety of reasons. Overall, we believe that our rough approach to approximating cost-effectiveness is reasonable in this case due to the general difficulty in estimating effectiveness across HSS interventions.[23] However, we caution readers from using our estimates for anything other than rough initial comparisons.

Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI)

What is it?

The IMCI is a strategy designed by the WHO and UNICEF “to improve access and quality of care for newborns and children in primary health care services” (WHO, 2014a). It has been recommended by the WHO and UNICEF since its launch in 1995 (WHO, 2014b). The main three components of IMCI, frequently quoted verbatim,[24] are:

1. improvement in the case management skills of health care staff through provision of locally-adapted guidelines on IMCI and activities to promote their use;

2. improvement in the overall health care system required for effective management of childhood illnesses, and

3. improvement in family and community health care practices

(Tulloch, 1999, p. 17)

The strategy is focused on preventing and managing the most common childhood illnesses in LMICs (e.g., pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, measles, and malnutrition) especially for children under the age of five. In practice, this appears to mean training health professionals (including nurses, doctors, and CHWs) in treating the most common childhood illnesses, and also in protocols to prioritize such care.

Reasons in favor

IMCI has shown significant success in various countries, standing out in the Ghana case study. One study estimated that IMNCI (IMCI adapted to include newborns) could avert a DALY at $24-$35, equivalent to 2,860-4,170x in Open Philanthropy’s cost-effectiveness terms (Prinja et al., 2016; calculated by us assuming that a DALY is valued at $100,000).

Our rough model indicates that IMCI may be a cost-effective intervention at around 2,700x. However, like all of the models discussed in this report, it is extremely rough and relies in large part on some key assumptions. In this case, the model is highly sensitive to a user-input parameter for the benefits that the average IMCI program is likely to attain, as a proportion of those measured in published studies.

IMCI seems to be able to reduce child mortality. In Egypt, it doubled the annual rate of under-five mortality reduction (from 3.3% to 6.3%),[25] while in Mozambique, infant and under-five mortality dropped by 49% and 42%, respectively (Witter et al., 2021). In Tanzania, child mortality decreased by 12% with IMCI, while in Bangladesh, child mortality may have been reduced by 13% (Gera et al., 2016). Additionally, combining IMCI with other interventions, like insecticide-treated nets in Benin, led to a 14.1% reduction in early childhood mortality (Rowe et al., 2011).

IMCI also seems associated with better quality of care, which is not always measured in terms of health outcomes. In Tanzania, IMCI led to better child assessments, diagnoses, treatment, and caregiver counseling compared to non-IMCI districts (Schellenberg et al., 2004). Countries that fully implemented IMCI made 3.6 times more progress toward Millennium Development Goal 4 (Boschi-Pinto et al., 2018). Furthermore, IMCI training improved the rational use of antibiotics and medication guidance, addressing challenges like overprescription (Gouws et al., 2004; Carai et al., 2020).

Reasons against

Despite the above successes, IMCI has not consistently improved health outcomes in all settings. Some studies found no association between IMCI and healthcare usage or positive health outcomes, potentially due to poor implementation (Huicho et al., 2005). For instance, in certain contexts, IMCI had little to no impact on stunting, wasting, or vaccine coverage (Gera et al., 2016, Gera et al., 2012). In our conversation, Kruk expressed skepticism about IMCI’s results, as she doesn’t consider it clear that the strategy has improved care aside from reducing stockouts.

The long history of implementing IMCI shows that scaling and implementation can be quite difficult. Many countries struggle to scale up while maintaining quality due to health system limitations and inadequate resources (Bryce et al., 2005). Implementation is often hampered by policy constraints (Ahmed et al., 2010) and by economic pressures in regions like Central Asia, where incentives for overprescription persist (Carai et al., 2019; Carai et al., 2020). Adherence to IMCI protocols is low, with some studies finding zero young infants and children receiving full protocol-adherent care in multiple countries (Bradley et al., 2022).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, IMCI is far from neglected. It has been implemented across vast swaths of the world (Boschi-Pinto et al., 2018), and it seems unlikely that much “low hanging fruit” still exists in this area.

Crucial considerations

The success of IMCI depends heavily on prioritization, leadership, and coordination among the various stakeholders in the system (policymakers, health workers, and logistical systems, as well as on high-quality engagement with the community), as discussed in Pinto et al. (2024) and Patel et al. (2018). A global survey revealed that while 81% of countries implemented IMCI, only 46% achieved full implementation, with resource gaps hampering progress, particularly in high-mortality countries (Boschi-Pinto et al., 2018). Reported key barriers frequently include insufficient funding, inadequate training, and the high demands on healthcare workers’ time (Reñosa et al., 2020). In South Africa, healthcare workers found the standard 11-day training insufficient, highlighting the need for extended training and mentorship, which we discuss further in the following section on supervision and mentorship in IMCI (Reñosa et al., 2020; Horwood et al., 2009).

Potential grants

Possible grants might include expanding and improving IMCI training and implementation to ensure more healthcare workers can effectively deliver services in underserved areas,[26] with partners like PATH, Save the Children, or icddr,b. Grants could also support policy advocacy for stronger IMCI integration into national health systems, potentially partnering with PATH or IntraHealth International to do so.

Our take

Our rough model indicates that, when implemented effectively, an IMCI program could surpass Open Philanthropy’s 2,000x bar, at around 2,700x. However, we doubt that IMCI on its own is likely to be a promising intervention for Open Philanthropy to fund. As the approach was developed in the 1990s and has been implemented in many countries, it does not seem particularly neglected (Boschi-Pinto et al., 2018).

Although we think it unlikely that many tractable opportunities exist to implement a brand-new IMCI program, there may be a lot of room for improvement on existing schemes. Boschi-Pinto et al. (2018) found that despite “high reported implementation rates, the strategy is not reaching the children who need it most, as implementation is lowest in high mortality countries.” Pinto et al. (2024) also highlighted many opportunities to improve existing IMCI systems.

As we discuss below, we believe there may be opportunities to improve the quality and reach of IMCI programs through supervision and mentorship. In addition, other interventions we discuss may have implications for the quality of IMCI work, including continuous quality improvement, extensions of CHW programs, and social accountability interventions.

Supervision and mentorship for IMCI providers

What is it?

As IMCI has been developed and scaled up over time, various implementation issues have arisen, as discussed in the previous section. One method that appears promising to keep IMCI interventions on track includes supervision and mentorship for providers, as discussed in a recent USAID Momentum report (USAID, 2023). With such additional support, which appears to be at a relatively low cost, some studies indicate that providers can significantly increase the quality of the IMCI care they provide (Manzi et al., 2018; Magge et al., 2015).

Reasons in favor

We were particularly interested in the results from the Mentorship and Enhanced Supervision at Health centers (MESH) mentorship program in Rwanda, which appears to show real potential for this intervention to “piggy-back” on existing IMCI implementations to significantly improve outcomes. Supervision and mentorship does not appear to be a widely implemented intervention, so it’s possible that this is a neglected area within the otherwise-crowded IMCI space.

Our rough model puts the potential cost-effectiveness of mentorship and supervision around 8,500x, making this the most cost-effective intervention we modeled in our analysis. Our model assumes that improvements in care quality are multipliers on the effectiveness of IMCI, with a user-input parameter reflecting the proportion of reported benefits the intervention is likely to actually create in a real program. For this discussion, we have set the parameter to 100%, but we note that our finding that this intervention is cost-effective by Open Philanthropy’s standards is robust to setting this parameter as low as 30%.

Our model is based heavily on the findings of Manzi et al. (2018), which found that the program improved IMCI implementation, leading to a 36% increase in correct diagnoses and a 20% increase in correct treatments after 12 months.[27] Ultimately, the authors found MESH to be cost-effective in improving IMCI quality of care, with costs per child correctly diagnosed and treated around $3 and $5, respectively.

In Benin, integrating IMCI training with supervision, job aids, and incentives resulted in a 27.3 percentage-point increase in the rate of recommended treatments compared to the control group over the 5-year follow-up period (Rowe et al., 2009).[28] Similarly, in Bangladesh, combining IMCI training alongside monthly supportive supervision led to sustained improvements in child healthcare quality over two years, even among minimally trained providers. Both high- and low-trained service providers achieved similar quality outcomes, highlighting the critical role of ongoing supervision in maintaining care standards, and also indicating the promise of low-trained CHW programs, which we discuss in a later section (Hoque et al., 2014).

In Rwanda, mentorship programs not only improved service readiness but also the quality of assessments, such as better registration of vital signs and detection of conditions like malnutrition and tuberculosis. Health posts that received mentorship showed significant improvements in composite scores for desirable and essential care metrics compared to non-mentored posts (Mirindi et al., 2024). A broader review of mentorship in LMICs found that mentorship positively impacted care quality in all studies reviewed (Schwerdtle et al., 2017), indicating that mentorship interventions consistently lead to better healthcare outcomes.

Reasons against

In Benin, the slow pace of IMCI training and the presence of low-quality care from untrained health workers diluted the impact of the intervention (Rowe et al., 2009). A follow-up study found that initial successes in improving supervision were eventually undermined by systemic issues such as coordination challenges, increased workloads, and the loss of key personnel, leading to a decline in supervision quality over time (Rowe et al., 2010).

Furthermore, we have found it quite difficult to model the health effects of “quality of care” interventions, both for this intervention and for CQI, below. Very little evidence exists linking MESH interventions to true health outcomes. In our very rough model, we have chosen to model IMCI supervision and mentorship as a multiplicative effect on the impact of IMCI alone, but we have low confidence in this strategy.

Potential grants

Potential grants in IMCI mentorship and supervision might include expanding formal mentorship programs, or setting up promising pilots similar to MESH. The original MESH studies were funded by the Doris Duke Foundation in partnership with Partners in Health, and we would recommend reaching out to both (Manzi et al., 2018). Additional promising implementing partners include Jhpiego (Ethiopia, Rwanda; Ingabire, 2018), USAID Momentum (Kenya, Indonesia; Maiyo & Onyango, 2024), or IntraHealth International (Mukeshimana et al., 2022). A similar opportunity could be funding supportive supervision programs that provide regular training, job aids, and incentives to ensure consistent service quality, with potential partners like Flanagan.

Other opportunities to improve mentorship and supervision might be technical or research-based. Digital supervision tools to streamline oversight and track performance in real-time could be another impactful area with overlaps to our CHW and social accountability interventions. Partners might include Wasunna (2018) or Dimagi (2024). Finally, investing in research to evaluate the long-term impact of mentorship programs could help refine these models, with 3ie as a potential partner (Nance et al., 2017).

Our take

Although the evidence is light, we believe that supervision and mentorship programs may be the most promising intervention we evaluated for this report. Our rough model (at the bottom of the IMCI model) indicates somewhat higher cost-effectiveness than IMCI alone, at around 8,500x. Our cost-effectiveness assessment is somewhat robust to a user-input parameter estimating the percentage improvement in IMCI care quality from such programs, which, in accordance with the other interventions discussed, we have set around 100% of the published estimates.

While IMCI is very unlikely to be neglected in areas with implementable programs, our impression is that associated mentorship and supervision is still neglected, and could be a tractable way to leverage the impact of existing investments in IMCI.

Community health workers (CHW) / service extensions and health posts

What is it?

CHW interventions have been a key facet of LMIC healthcare systems for decades. Starting as early as the 1970s, countries like Brazil (EGH, 2020) and India (Strodel & Perry, 2019) began to recruit local community members to train in some basic primary healthcare skills. With the establishment of global health initiatives like the Global Fund (established 2002) and PEPFAR (2003), CHWs became central to scaling up HIV treatment, care, and prevention programs both for national governments, IGOs, and NGOs.

According to Hasan of BRAC, CHWs are often selected from the community due to local links and ownership. CHWs often support vaccination campaigns, health education, and basic healthcare services in rural communities. In our case studies, several countries, including Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Ghana, have adopted CHW programs or other task-shifting strategies that allow less-trained community members to assist with healthcare burdens.

Reasons in favor

CHW programs have long been used to target maternal, neonatal, and child mortality. Hasan noted the historical success of such interventions in Bangladesh, where cultural and logistical challenges limit access to government health facilities, and CHW programs like those of BRAC are able to bring healthcare to a much larger share of the population.

In comprehensive programs, postpartum hemorrhage was reduced by 24% to 66% (Jennings et al., 2017), and neonatal mortality saw a 25% reduction, along with 22% in perinatal mortality and 15% in infant mortality (Gogia & Sachdev, 2016). In a review of studies in high-risk settings, CHW home visits lowered newborn mortality by 30-61% (Aboubaker et al., 2014). In Uganda, a micro-entrepreneurial CHW program reduced under-5 mortality by 27% (Björkman Nyqvist et al., 2016). CHWs also improved health behaviors, such as malaria prevention, breastfeeding promotion, and newborn care (Gilmore & McAuliffe, 2013), and increased child health check-ups by 24% (Ballard & Montgomery, 2017). The latter study also found that CHWs improved access to essential maternal and neonatal health services by 31%, including antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and facility-based deliveries.

More recently, CHW programs have begun to see success for non-communicable diseases (Mbuthia et al., 2022). One study found such programs effective at doubling tobacco cessation rates and improving glycemic control, with an HbA1c reduction of 0.83% in diabetes patients (Jeet et al., 2017). CHW-led hypertension management reduced systolic blood pressure by 5 mmHg and diastolic by 2.88 mmHg (ibid).

In our section profiling Last Mile Health, we discuss several additional studies of the organization’s CHW programs which found a 21% decrease in “disease prevalence for children under five” and a 40 percentage point increase in the use of both oral rehydration therapy and rapid malaria testing (White et al., 2022).

Many studies have found CHW programs to be cost-effective by various metrics. In Mozambique, the annual cost per beneficiary was just $47.12 (Bowser et al., 2015), while in Bangladesh, CHW-led severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment was far more cost-effective at $26/DALY compared to inpatient care at $1344/DALY (Puett et al., 2013). Task-shifting to CHWs in tuberculosis, HIV, and childhood illness programs has been shown to be cost-effective and yield substantial healthcare savings (Watson et al., 2018).

Reasons against

The evidence supporting some CHW interventions, particularly for non-communicable diseases, is of variable quality, with moderate evidence for tobacco cessation but low-quality evidence for glycemic control (Jeet et al., 2017). In South Africa, while CHW programs reduced cardiovascular events by 2%, their estimated cost-effectiveness ratio of $320 per DALY averted does not meet Open Philanthropy’s bar (Gaziano et al., 2014).

Effectiveness tends to be higher in high-risk, low-resource settings (Gogia & Sachdev, 2016), but interventions must be contextually adapted. For example, the impact of CHW home visits varied significantly between Bangladesh (67% reduction in neonatal mortality with day 1 visits) and Ghana (8% reduction, Aboubaker et al., 2014). While CHWs reach many marginalized groups, barriers such as geographic location, financial constraints, and sociocultural factors continue to limit access to care for some populations, with rural areas often underserved (Ahmed et al., 2022). Furthermore, in places like rural Mali, imperfect coverage of CHWs led to marginally higher costs per child treated ($238) compared to facility-based care ($188, Rogers et al., 2018).

Our rough model[29] indicates that CHW programs may have a cost-effectiveness around 1,000x, meaning that they are not one of the most cost-effective interventions analyzed. CHW programs also appear to have been scaled up across much of the developing world, so we doubt that many neglected but tractable opportunities exist for transformative care. Many CHW interventions are likely to require large amounts of ongoing financial support, and do not offer a clear path toward highly cost-effective or leveraged interventions.

Crucial Considerations

CHW programs perform best when they receive strong support, including financial incentives (Woldie et al., 2018; Bowser et al., 2015) found that including salaries for community health workers actually improved cost-effectiveness compared to scenarios in which they were unpaid. However, community health workers are frequently unpaid or underpaid, which raises concerns related to fairness, service quality, and sustainability. Kruk noted that relying on often-unpaid community members to perform crucial health services can raise serious fairness concerns. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, paid CHW programs would require up to 27% of government healthcare spending, making them reliant on external funding (Taylor et al., 2017).

Kruk also highlighted that the promising results of CHW programs has led some leaders to pile responsibilities onto the shoulders of the workers, which may not be sustainable practice. Indeed, Kok et al. (2014) found that high workloads and lack of clarity in roles can undermine program success.

Quality supervision and integration into the health system and with other health interventions are essential for success (Blanchard et al., 2019). Hasan particularly stressed the need for referral linkages in community health interventions, especially in countries with large populations, where screening must connect to higher-level diagnostics. Bangladesh relies heavily on household visits and local outreach, and Hasan believes these community-level interventions are essential, especially with challenges like climate shocks. Improving governance and strengthening community involvement are critical, as governance gaps (e.g., budget shortfalls) often undermine the sustainability of health system improvements. Organizations like BRAC have begun using tools like mHealth apps to assist CHWs in referrals, diagnostics, and decision-making, according to Hasan. Such innovations have been found to significantly improve quality of care and treatment accuracy in childhood infection management (Mahmood et al., 2020).

Potential grants

Possible grants in Community Health Worker/ service extension programs might include expanding training and certification programs to improve the skills of CHWs in low-resource areas. Potentially promising partners include BRAC (Joadar et al., 2021), CARE (2024), PIH, and Last Mile Health. Grants could also focus on supplementing CHW salaries and providing incentives to boost retention and service quality, with partners such as VillageReach (Alban & Ngwira, 2023). Policy advocacy for integrating CHWs into national health systems could be supported by the Last Mile Health, or potentially by the Population Council (2024) or IntraHealth International (Guinot, 2023).

Other options could involve ways to make CHWs more effective. That might mean introducing mHealth tools for CHWs to enhance service delivery and data collection, with organizations like PATH, Medic Mobile (Wasunna, 2018) or Dimagi as potential partners. Alternatively, it could include logistics and transportation support to ensure CHWs can reach remote communities, with Riders for Health or Transaid as potential grantees.

Our take

Our rough model should be taken as little more than a guide of the order of magnitude associated with this intervention. Furthermore, while CHW programs have a long track record of improving maternal, neonatal, and child health outcomes, these programs are not particularly neglected, with many countries having scaled them up extensively. There may, however, still be opportunities to improve quality or introduce innovative tools, such as mHealth solutions, to enhance the impact of existing CHW programs.

Social accountability interventions / Community score cards

What is it?

Community social accountability tools, such as community scorecards (CSCs), allow citizens to participate in holding service providers and public officials accountable. These tools help improve governance and service delivery by enabling civic engagement. CSCs, in particular, were developed by CARE in Malawi in 2002 and have been used to increase community participation in the decision-making and oversight of public services, especially in maternal and child health (Post et al., 2014, p. 1; Witter et al., 2021, p. 20).

Reasons in favor

In our conversation, Hasan of BRAC stressed the importance of various community awareness and feedback mechanisms, including scorecards as well as social mechanisms such as mothers’ support groups. He highlighted success in using these methods to promote immunization and health service utilization in Bangladesh and Pakistan.

A review of CARE’s CSC programs across five countries between 2002 and 2013 found significant improvements in governance outcomes, such as feelings of citizen empowerment and accountability, as well as service outcomes like increased health center attendance and facility deliveries. The CSC approach also improved patient-centered care, including timeliness, respect, and equity, mainly through changes in provider behavior with minimal additional resources (Gullo et al., 2016).

Multiple evaluations have shown that CSC interventions significantly improve health outcomes. For example, in Uganda, an RCT on community-based monitoring[30] improved healthcare quality and led to a 33% reduction in under-5 mortality (Björkman & Svensson, 2009). The program resulted in increases in facility deliveries, family planning utilization, immunizations and infant weight. These improvements in health delivery and outcomes persisted after four years despite minimal follow-up (Nyqvist[31] et al., 2017). Gullo et al. (2017) found that the CSC program in Malawi led to a 20-percentage point increase in the likelihood of receiving antenatal care at home.[32] Similarly, CSC interventions were associated with improved childhood immunization rates (Jain et al., 2022), with the most effective interventions being those with embedded community engagement.

Our rough model indicates cost-effectiveness around 3,100x. A quick calculation in Björkman and Svensson (2009) showed the intervention might save a child under 5 for around $300, which would be close to 10,000x in today’s dollars in Open Philanthropy terms.

CSC programs have consistently demonstrated improvements in healthcare access and utilization. Gullo et al. (2016; 2017; 2020) reported improvements in contraceptive use, home visits, and service quality in Malawi. Further, studies from Bangladesh and Cambodia reported improvements in pediatric care and health service utilization (Hanifi et al., 2020; Edward et al., 2020).

Furthermore, CSCs may be able to genuinely increase perceived quality of care and foster a sense of community empowerment. Molina et al. (2017) found a reduction in perceived corruption by 8 percentage points and increased health service access and immunization rates by 56%. Balestra et al. (2018) found that community-based monitoring improved service performance and fostered empowerment, especially among marginalized groups, and the systematic review by Gullo et al. (2016) found similar results. .

Reasons against

Not all studies on community accountability mechanisms have shown positive outcomes. For instance, Molyneux et al. (2012) found mixed or negative results for various accountability structures due to unclear roles, lack of resources, and resistance from health workers. Donato et al. (2018) replicated Björkman and Svensson’s (2009) study but found less robust estimates for child mortality reductions and no effect on stunting. Similarly, Mohanan et al. (2020) noted that service delivery improvements did not always result in sustained health outcomes, particularly for child mortality and nutritional outcomes. Resistance from healthcare providers and biases against certain interventions, like family planning, can also hinder the effectiveness of CSCs (Onyango et al., 2022).