This short research summary briefly highlights the major results of a new publication on the scientific evidence for insect pain in Advances in Insect Physiology by Gibbons et al. (2022). This EA Forum post was prepared by Meghan Barrett, Lars Chittka, Andrew Crump, Matilda Gibbons, and Sajedeh Sarlak.

The 75-page publication summarizes over 350 scientific studies to assess the scientific evidence for pain across six orders of insects at, minimally, two developmental time points (juvenile, adult). In addition, the paper discusses the use and management of insects in farmed, wild, and research contexts. The publication in its entirety can be reviewed here. The original publication was authored by Matilda Gibbons, Andrew Crump, Meghan Barrett, Sajedeh Sarlak, Jonathan Birch, and Lars Chittka.

Major Takeaway

We find strong evidence for pain in adult insects of two orders (Blattodea: cockroaches and termites; Diptera: flies and mosquitoes). We find substantial evidence for pain in adult insects of three additional orders, as well as some juveniles. For several criteria, evidence was distributed across the insect phylogeny, providing some reason to believe that certain kinds of evidence for pain will be found in other taxa. Trillions of insects are directly impacted by humans each year (farmed, managed, killed, etc.). Significant welfare concerns have been identified as the result of human activities. Insect welfare is both completely unregulated and infrequently researched.

Given the evidence reviewed in Gibbons et al. (2022), insect welfare is both important and highly neglected.

Research Summary

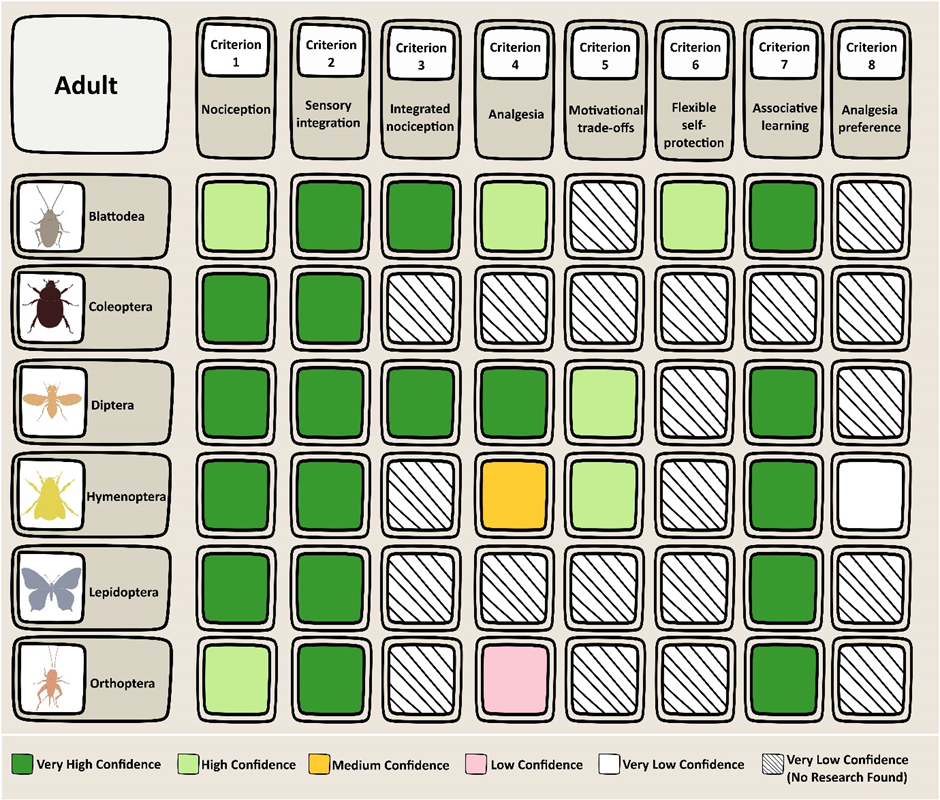

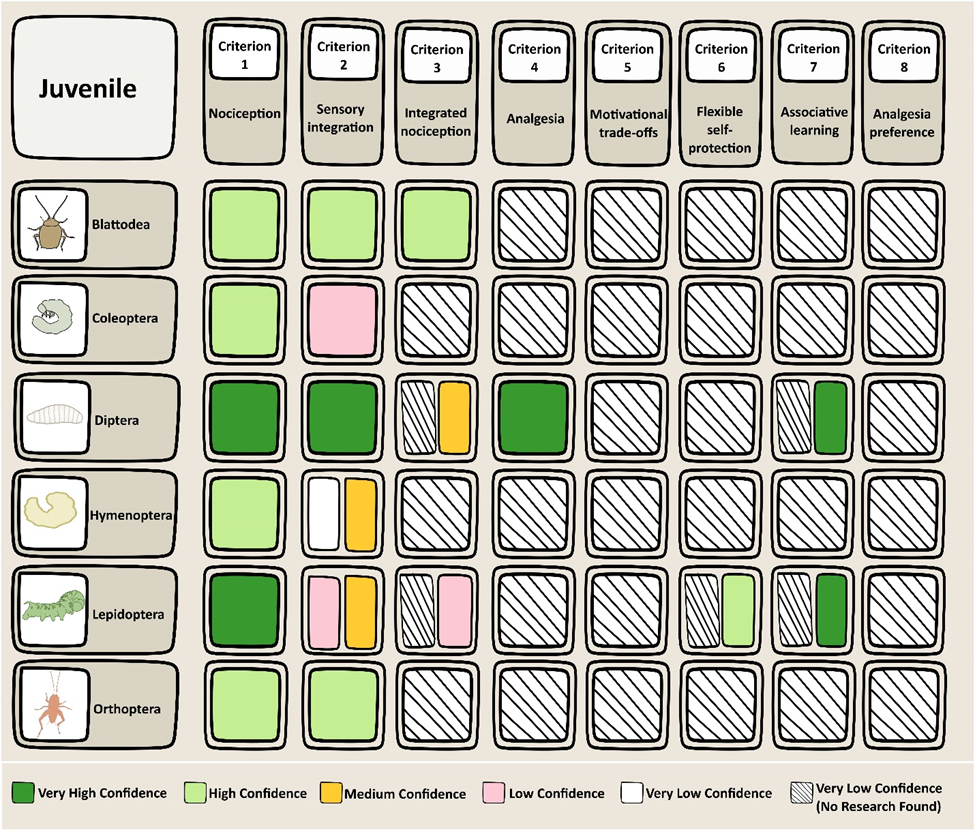

- The Birch et al. (2021) framework, which the UK government has applied to assess evidence for animal pain, uses eight neural and behavioral criteria to assess the likelihood for sentience in invertebrates: 1) nociception; 2) sensory integration; 3) integrated nociception; 4) analgesia; 5) motivational trade-offs; 6) flexible self-protection; 7) associative learning; and 8) analgesia preference.

- Definitions of these criteria can be found on pages 4 & 5 of the publication's main text.

- Gibbons et al. (2022) applies the framework to six orders of insects at, minimally, two developmental time points per order (juvenile, adult).

- Insect orders assessed: Blattodea (cockroaches, termites), Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies, mosquitoes), Hymenoptera (bees, ants, wasps, sawflies), Lepidoptera (butterflies, moths), Orthoptera (crickets, katydids, grasshoppers).

- Adult Blattodea and Diptera meet 6/8 criteria to a high or very high level of confidence, constituting strong evidence for pain (see Table 1, below). This is stronger evidence for pain than Birch et al. (2021) found for decapod crustaceans (5/8), which are currently protected via the UK Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022.

- Adults of the remaining orders (except Coleoptera) and some juveniles (Blattodea, Diptera, and last juvenile stage Lepidoptera) satisfy 3 or 4 criteria, constituting substantial evidence for pain (see Tables 1 + 2).

- We found no good evidence that any insect failed a criterion.

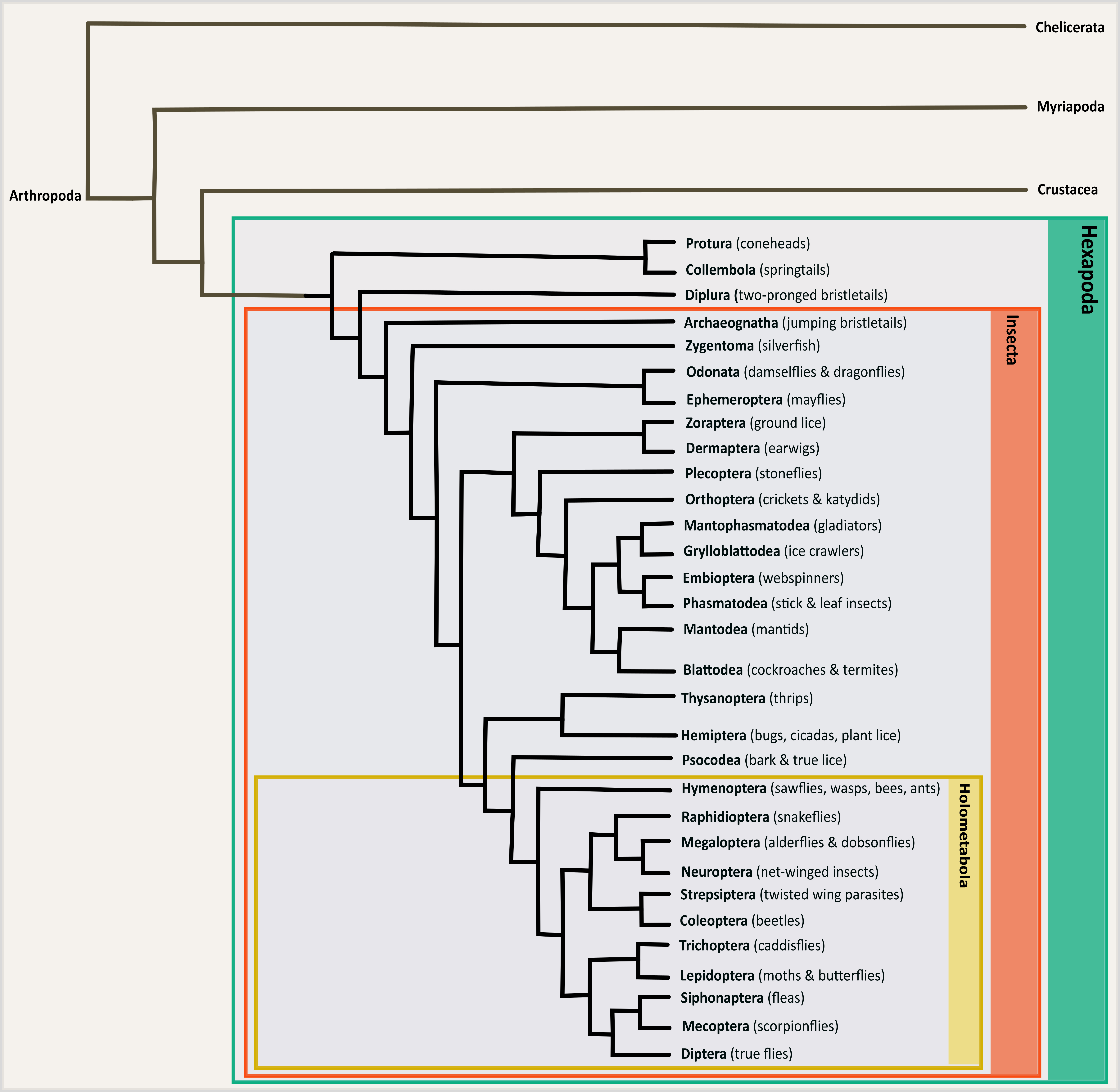

- For several criteria, evidence was distributed across the insect phylogeny (Figure 1), including across the major split between the hemimetabolous (incomplete metamorphosis) and holometabolous (complete metamorphosis) insects. This provides some reason to believe that certain kinds of evidence for pain (e.g., integrated nociception in adults) will be found in other taxa.

- Our review demonstrates that there are many areas of insect pain research that have been completely unexplored. Research gaps are particularly substantial for juveniles, highlighting the need for more work across developmental stages.

- Additionally, our review could not capture within-order variation in neuroanatomical development or behavior, as most data within an order were from only one or two species. Further research on within-order variation, particularly for juveniles, will be necessary.

Table 1. Confidence level for each criterion for adults of each focal insect order.

Table 2. Confidence level for each criterion for juveniles of each focal insect order.

Contact Information

Questions on the study results should be directed to Dr. Lars Chittka, the corresponding author, here: l.chittka@qmul.ac.uk

Questions on how the effective altruism community can improve insects’ lives can be directed to Rethink Priorities here; and/or by emailing Dr. Meghan Barrett, here: meghan@rethinkpriorities.org

Acknowledgements

Barrett collaborates with Rethink Priorities on topics related to insect welfare. However, this project was not funded by or associated with Rethink Priorities and was conducted independently by Barrett, in collaboration with Gibbons, Crump, Sarlak, Chittka, and Birch.

I fail to see any lack of distinguishing as I do not see any claim on suffering or capacity to suffer in insects, only on insects' abilities to feel pain.

How physical pain relates to subjectively perceived suffering is a whole other topic, and as far as I can tell no subject to this review. (Though I've only read this post, not the review itself.)

I do see that pain-feeling is usually perceived as something innately suffering-inducing, and I see why that's the case. If pain is not somewhat negative for the organism experiencing it, why would that mechanism establish itself across whole species in the first place? Could be that pain in insects acts merely as a reflex trigger and no experience/suffering in the moral sense is involved at all, but I really argue that this is a whole other claim and topic.

The Open Phil report you linked shows quite well how little we know and how complex this issue is, and that jugdements rely heavily on claims and intuitions due to lack of understanding.

So as we do not really know how the ganglions of insects (let alone our brains) work and what consciousness or conscious experience really is about, I' be very careful with making definite claims about the suffering capacities of other species.

As far as I can tell, the authors of this review made a good job of evaluating the physical ability of insects to feel pain. This is but the first step to assign moral patienthood to insects; it's a necessary, but not sufficient criteria.

The likelihood of an organism to be able to suffer is significantly higher if that organism is known to feel pain. I personally tend to err on the worse case and assume pain-feeling organisms are suffering, rather than risk neglecting substantial suffering as the odds seem high enough. (But that's just my personal take.)

I see how the concepts get mingled up inappropriately, but I would not go as far as to demand a clarification on that from any scientific publication dealing with pain (in organisms other than human), especially since there is no sufficiently backed-up concept of consciousness or moral patienthood. In my opinion arguing about wether pain-feeling and suffering can be used anagolous should happen, but it's probably not the responsibility of the authors here.