Recently I have been thinking a lot about the impacts of longtermist versus neartermist causes, the relationships between different generations, and the value or (lack there of) in longevity research.

With this mishmash, an interesting analogy occurred to me: When discussing longevity, people often make the distinction between lifespan and healthspan. What if not just humans as individuals, but humanity as a whole had a lifespan and a healthspan?

I wrote the following as a journal entry:

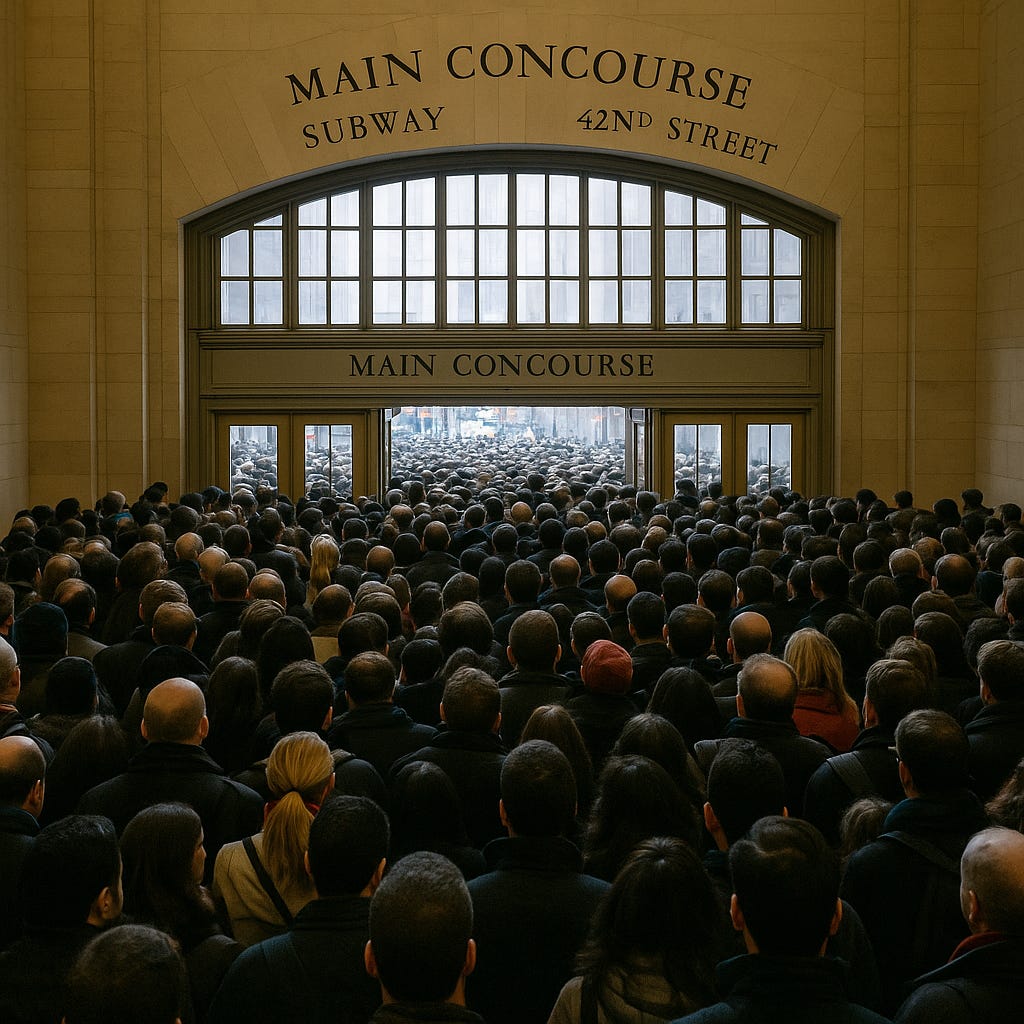

I don’t want to think about what happens or will happen to humans in 10,000 years. I want to think about what is happening right now, about things within my control, about securing the next hot meal for me and my family, about keeping a roof over my head.

I do like to imagine humans in the future, how there lives might be different or better. I want to leave this Earth a little better than I found for future generations, but I don’t think that involves solely focusing on existential risk. Talk of existential risks annoy me. How much does analyzing and researching existential risks actually mitigate them? What else can we actively be doing? What about all the people who are suffering now? Not tomorrow, not in ten thousand years. Right now.

To “ensure the future of humanity.” That is a losing battle. I’m not saying that I want humanity to have a premature death. I’m not saying that humanity shouldn’t try to live as long as it possibly can. I’m just saying that the end of humanity is not a question, it is a matter of fact, a certainty. One day humanity will die. One day this planet will die, one day this galaxy will die. Everything dies, everything changes. All good things must come to an end.

I see a parallel between discussions of longevity and aging research, and discussions of humanity’s future. In longevity research, people distinguish lifespan from health span. There is also controversy surrounding the idea of an “aging escape velocity.” Blatantly, some silly euphemism for immortality. I do believe that we should increase both our healthspans and lifespans, primarily healthspans though. A larger number of good quality years is preferable to a smaller number of good quality years. Although maybe not, depending on the total years.

Can individuals or can humanity ever fully escape aging or extinguishment? Intuitively, I don’t believe so. Assuming that humanity will end, the argument for longtermism is akin to the argument for increasing someone’s lifepsan, with less regard for healthspan (but in EA style longtermism, it seems there is a prerequisite belief in an “escape” of some kind). The argument for neartermism is akin to the argument for increasing someone’s healthspan, with also some small to moderate life extension as an unintended consequence. This analogy leads me to lean more towards near term causes.

However, underneath this analogy, there still exists an unanswered question. What is a healthy or thriving humanity? This question must be answered and healthspan must be defined before any discussion of humanity’s healthspan becomes truly meaningful.

The issues of ambiguous definitions and imperfect measurements are nothing new. EAs and outsiders have criticized the usage of QALYs and DALYs and called for better measurements of well being to try to perform better cost-benefit analyses of different causes. Healthspan for humanity might be a much trickier thing to measure (though I’m sure economists have all sorts of measurements for financial health of nations and the globe). Should we set out to further define or measure humanity’s health, or accept that we have to grapple with decisions that defy measurement? Both?

I wrote this journal entry while feeling disillusioned with Effective Altruism, longtermism, and rationalism, even though I agree and try to align myself with many of their central tenets.

I’m not very far into it, but currently reading a book called Recapture the Rapture by Jamie Wheal, which has helped to combat my disillusionment.

Recently I have been thinking a lot about the impacts of longtermist versus neartermist causes, the relationships between different generations, and the value or (lack there of) in longevity research.

With this mishmash, an interesting analogy occurred to me: When discussing longevity, people often make the distinction between lifespan and healthspan. What if not just humans as individuals, but humanity as a whole had a lifespan and a healthspan?

I wrote the following as a journal entry:

I wrote this journal entry while feeling disillusioned with Effective Altruism, longtermism, and rationalism, even though I agree and try to align myself with many of their central tenets.

I’m not very far into it, but currently reading a book called Recapture the Rapture by Jamie Wheal, which has helped to combat my disillusionment.